Bettina Samson‘s work isn’t always immediately graspable. By the time you have got your head around any one particular piece of subject matter that goes into her abstract sculptures—which might include razed car parks, astrological figures, or the dog who discovered the prehistoric Lascaux caves in France—the artist might well already be five paces ahead in her thinking. Samson’s pieces, sometimes made through trial-and-error experimental processes, begin with one subject and end up somewhere else. These points on the compass won’t necessarily have a discernible link between them—that is, if you’re not in Samson’s mind. She creates disjointed relations, marries diverse elements, whether in terms of intellectual content behind work or in the media she uses. The pieces bridge temporal or spatial chasms, allowing Samson to approach the social, the relational and the historical all at once: a malleable and fertile environment for her ideas. I went to visit her at her studio in Aubervilliers, north-east of Paris, on the first week of autumn.

Bettina Samson‘s work isn’t always immediately graspable. By the time you have got your head around any one particular piece of subject matter that goes into her abstract sculptures—which might include razed car parks, astrological figures, or the dog who discovered the prehistoric Lascaux caves in France—the artist might well already be five paces ahead in her thinking. Samson’s pieces, sometimes made through trial-and-error experimental processes, begin with one subject and end up somewhere else. These points on the compass won’t necessarily have a discernible link between them—that is, if you’re not in Samson’s mind. She creates disjointed relations, marries diverse elements, whether in terms of intellectual content behind work or in the media she uses. The pieces bridge temporal or spatial chasms, allowing Samson to approach the social, the relational and the historical all at once: a malleable and fertile environment for her ideas. I went to visit her at her studio in Aubervilliers, north-east of Paris, on the first week of autumn.

Where are we? Is this an artists’ community? Is it also residential?

We are forty artist studios scattered over 900 social housing units at La Maladrerie. It was created by architect Renée Gailhoustet in the late 1970s who developed these spaces so each has its own specificity. Each unit is a different size and shape and there are no straight lines in the whole estate; you can’t get from one point to another without taking a turn or going down a small passage. When I first moved here I’d get lost all the time. There was no map and it is spread out over hectares because none of the buildings are higher than four floors or so. But what is great about it, is that its organization of space favours encounters. It also becomes a huge playground for the kids in the area, most of whom don’t get to leave much.

Do you think that this space where you live and work—a space underpinned by utopic social function—influences your work at all?

I look at these spaces every day. I’m not sure exactly how it enters into my work, but it is something I am always observing. I’m completely fascinated by it. They knocked down the car park at the edge of the estate recently and there was something very apocalyptic about it once the machines had destroyed everything. But then later some landscape gardeners came along and they planted various rock plants, and through the interstices in the asphalt, greenery began to emerge. It’s now the second year, and these plants have since decomposed, providing more fertile soil for new plants to emerge. It will develop in a completely autonomous way.

It’s also fascinating because they started to bring in shepherds from time to time to tend to this wasteland, backing on to some privately rented spaces that are in total disrepair. I came home one day and there were a number of sheep on the land. I couldn’t help but think of Blade Runner and the electric sheep.

“I made a sculpture but it isn’t fired, so it’s destined to crumble and I kind of like that. I didn’t have any specific training in ceramics, so I don’t follow the rules in that sense”

Can you explain your working process? The wall of your studio is covered with texts and photos and notes that all seem to be grouped thematically. How does this work?

I’ve worked this way since I studied at the Beaux Arts in Lyon in 2001. I need to space things out and to put things into relation with one another. These relations often give way to new ideas or new relations that are tacked on.

And what do these clusters of research end up as? Exhibitions, or single works, or something else entirely?

Everything on this wall right now falls under the category of on-going projects, but frequently these kinds of starting points will also give way to dead ends. I’ve recently become obsessed with the astrological figure of the month of March who can be found in the Renaissance frescoes in the Hall of Months at the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara. I tried to create something related to him. It is understood that this figure spans the ancient Greek, Persian and Indian astrological calendars. He has a majestic posture despite his rags. He clearly holds a rope knotted around his waist, with the illusion that he could undo it at any time, revealing himself. I compared images of him with images of Haitian “Kanaval”, when a group of men turn into figures of the “Lans è Kod” to re-enact the act of capture by slave traders by slinging rope around one another.

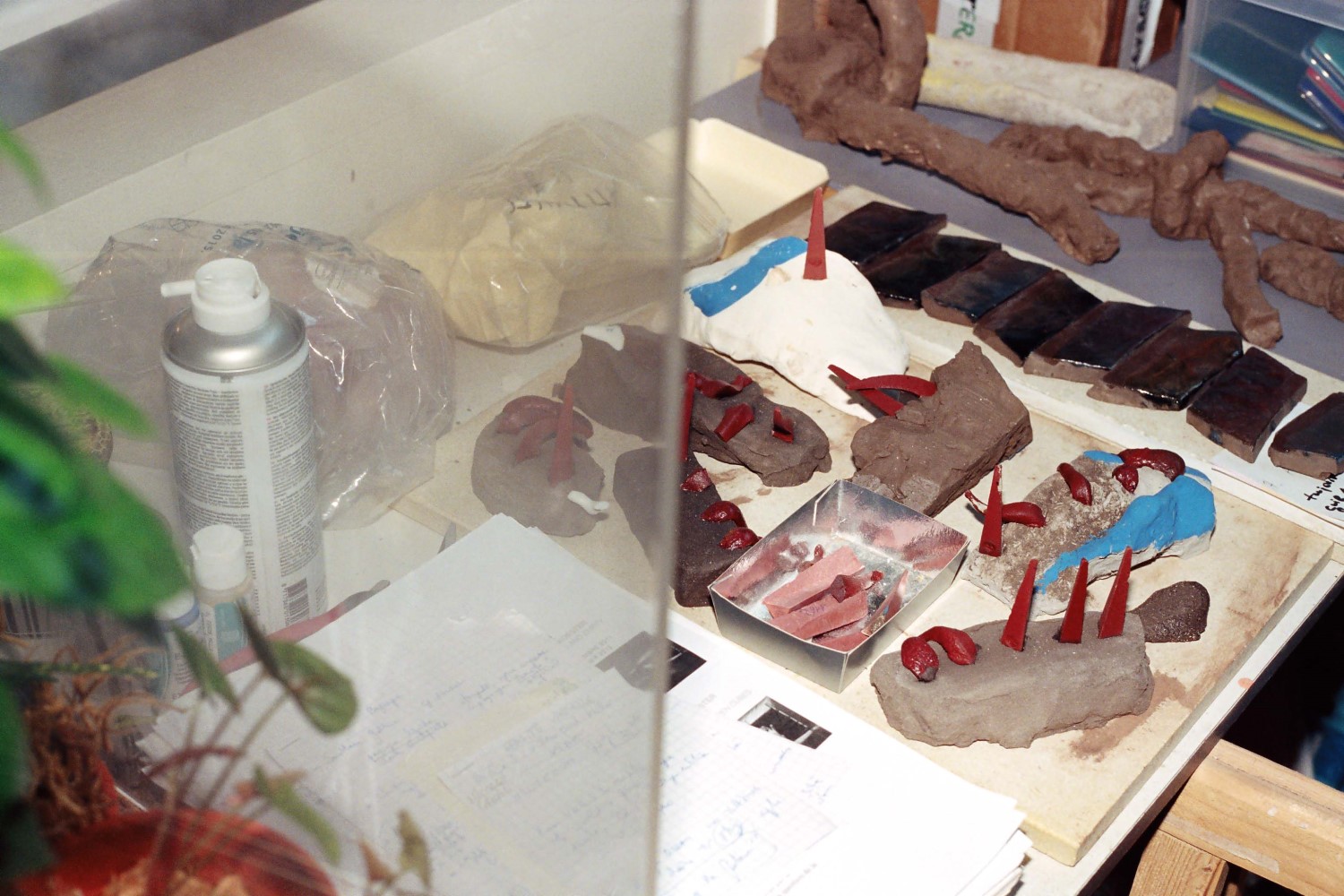

I made a sculpture of this character, of the bottom half of his body, but it isn’t fired, so it’s destined to crumble and I kind of like that. Sometimes even after all the research there are pieces which don’t work and I need to start again or go deeper into formal or practical research with material tests and experiments. There are also lots of accidents in my work, unintentional results that can inspire all kinds of new projects. I didn’t have any specific training in ceramics, so I don’t follow the rules in that sense.

“Each unit is a different size and shape and there are no straight lines in the whole estate; you can’t get from one point to another without taking a turn or going down a small passage.”

I’m also thinking a lot about robot dogs created to keep people company at the moment; the dog that discovered the Lascaux caves in 1940 was called Robot. Research into him and his adolescent owner got me to reading on those small I-Cybie toy robot dogs that were created in Hong Kong between 2001 and 2006. They look exactly like the terracotta sculptures of dogs that would stand inside some tombs in China during the Han period 2000 years ago. It’s interesting to think about canine company over the centuries. Now they’re making robots for dogs, they can take care of the dog while you’re out of the house working. I want to see how robot dogs for humans interact with robots made for dogs.

You’ve spoken about how you find it difficult to link together the diversity of your work, but is it fair to say that there is always an element of trying to straddle time and space? Which is also something you’ve spoken about as the socio-political element of your work.

I work by suspending rationality, I put things into relation that have no relationship or for whom time has undone any possible relationship. I’m pretty influenced by Aby Warburg who thinks about the Italian Renaissance, serpentine movement and pagan figures simultaneously through the rituals of Native Americans. I try and have the same deconstructive approach, without necessarily adopting a critical position. I am more interested in unearthing the relationships between things and then creating a third element.

It’s almost as if I were taking two disparate chemical elements, then researching the material and possible formal elements which would resolve in the relation between these disparate elements. I call it a precipitate like in chemistry.

Most of my ceramic work however is created without intention. There are some influences that I have in mind of course, but it’s something I create almost without thinking; there are no preparatory sketches, nothing to copy from.

Your work is often larger than the confines of this studio. What other projects are you working on?

I’m currently working on a project on the banks of the Garonne near to Bordeaux where I’ll install a large-scale public commission. It will incorporate various different artisanal and industrial practices in order to create a steam-powered organ which will run each day as the tide turns, with high pressure steam provided by an enormous waste-treatment plant. The music played corresponds to the repressed history of Bordeaux’s cross-Atlantic trade. It’s a big project and along with the City of Bordeaux and the production company Zebra3, I’ve been working on it for four years now!

All photography by Jules Faure