Liza Lou is eyeing the thickly impastoed painting on the wall of the gallery’s back room, artist unknown. “It seems a bit dense,” she tells me, making a hammering motion with her hand and adding some smash-crash-tinkle sound effects. “It just needs some air, a little…”—she pauses and cocks her head—“respiration.”

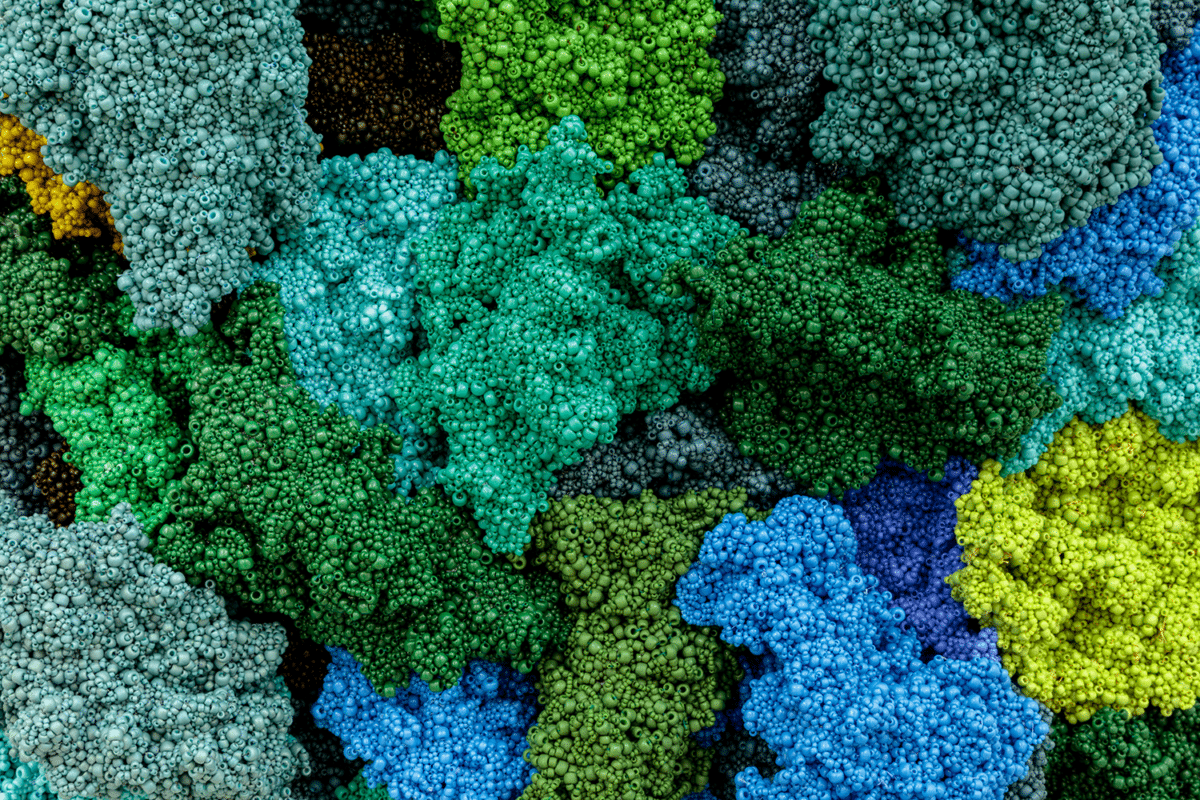

Of course, Lou only wants to help. She doesn’t want to damage the painting, just remove a little of its excess in order to improve it. “The willingness to destroy something to create something new is central to my new body of work,” she says, while carefully sipping tea from a white china cup. Lou, who is known for sculptures tirelessly constructed from thousands of glass beads, has recently begun exploring a new set of techniques; painting the beaded panels with oil paints, cutting them with scissors and smashing them with a hammer to reveal a finely woven net of threads beneath.

Lou is small and slight; precise in her movements and speech, but in process videos on Instagram she looks like a bank robber, or a forgotten member of Pussy Riot. When pulverizing the beads with small hammer, Lou wears a balaclava that covers her face and neck, headphones and mirrored sunglasses. (If she doesn’t take proper precautions, glass shards from the crushed beads could penetrate her eyes and ears.) “I feel like I’ve only just scratched the surface of this approach,” Lou says. She still has territory to explore and questions to answer, such as “How can you carve a painting? At what point does a painting become a sculpture?”

As sculptors go, Lou is to beads as Rodin was to marble; her intimacy with the material is deep, her devotion to it is legendary. Kitchen (1991–1996), Lou’s first major work, is a masterpiece of accumulation. It took Lou five years and millions of beads to construct the meticulously detailed life-sized room and its contents which included boxes of Frosted Flakes, faux bois cabinet doors and the water coming out of the tap.

“How can you carve a painting? At what point does a painting become a sculpture?”

In Kitchen the beads act as a sort of bright, shiny decorative layer, but as Lou’s career progressed she began to explore beyond the optical surfaces of the material. In recent years her work has become increasingly simple and abstract. She’s begun to deconstruct, carving away at her surfaces, or creating freestanding vertical piles of beads that resemble clusters of lichen or mushrooms. “At first I found that with beads I could transform ordinary things into something otherworldly,” she says of her initiation to the medium. “But when you want to get to the essence of something you don’t have to put on a big show. You can actually do something quite small.”

The showstopper in Lou’s newest body of work isn’t small, but it is subtle, quiet in comparison to Kitchen. The Clouds (2015-2018), originally commissioned for the twenty-first Biennale of Sydney, is composed of 600 beaded squares, many are painted with daubs of hazy blues and yellows and aired out by Lou’s hammer. Installed at Lehmann Maupin gallery’s new Chelsea flagship on West 24th Street, the work is over eighteen feet tall, filling the entirety of the gallery’s back wall. The most colourful squares are closest to the ceiling, guiding the eye upward to the skylight above where real clouds float. “I want people to look up,” Lou explains. “You can change your mood based on the architecture of your body, the way you hold yourself. When we’re depressed we have a tendency to hunch over, to look down, which we’re doing all the time on our phones. So looking up at the clouds is aspirational, and it allows us time to free associate and dream.”

After a decade of living full-time in Durban, South Africa, and working on-site with a team of Zulu beaders there, Lou returned to California three years ago. The quiet of her empty studio was a big adjustment. “I went from working with these fabulous women, from the noise and tumult of a room full of so much joy, to total silence,” she says. “I hadn’t had that level of solitude since I made Kitchen. In some ways it brought me home to myself.”

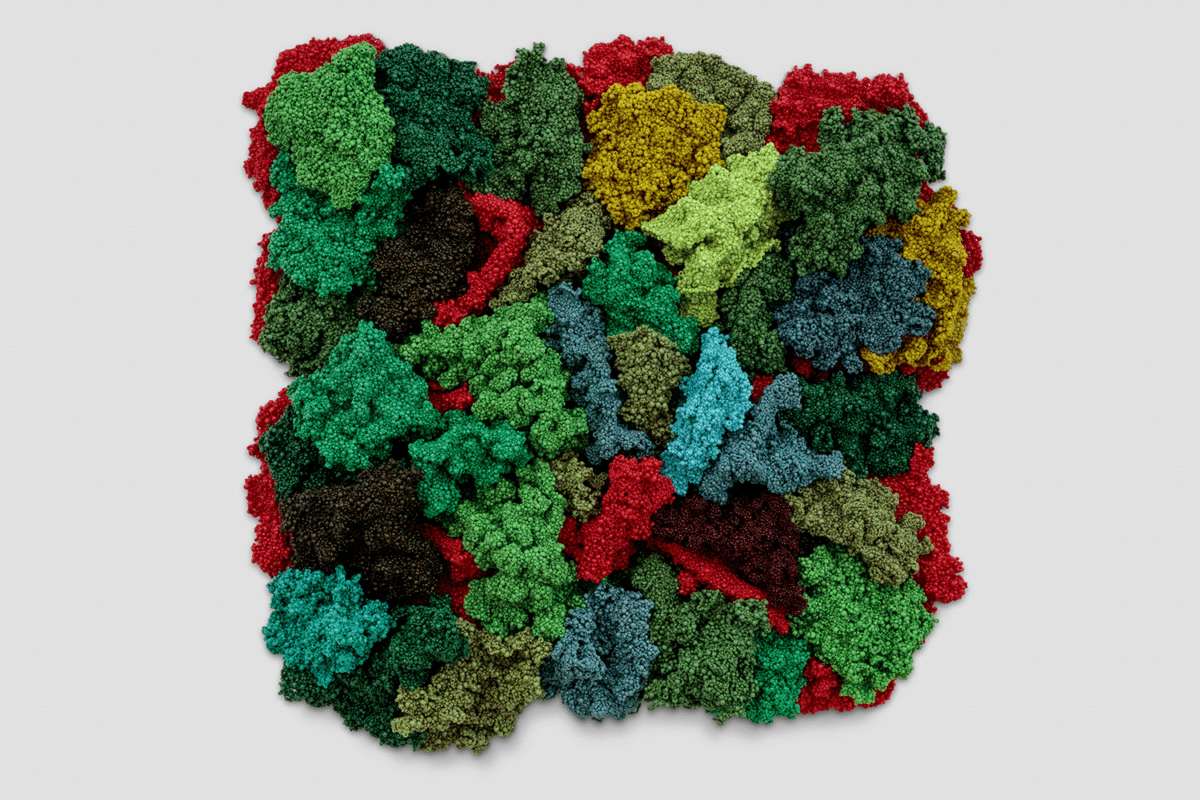

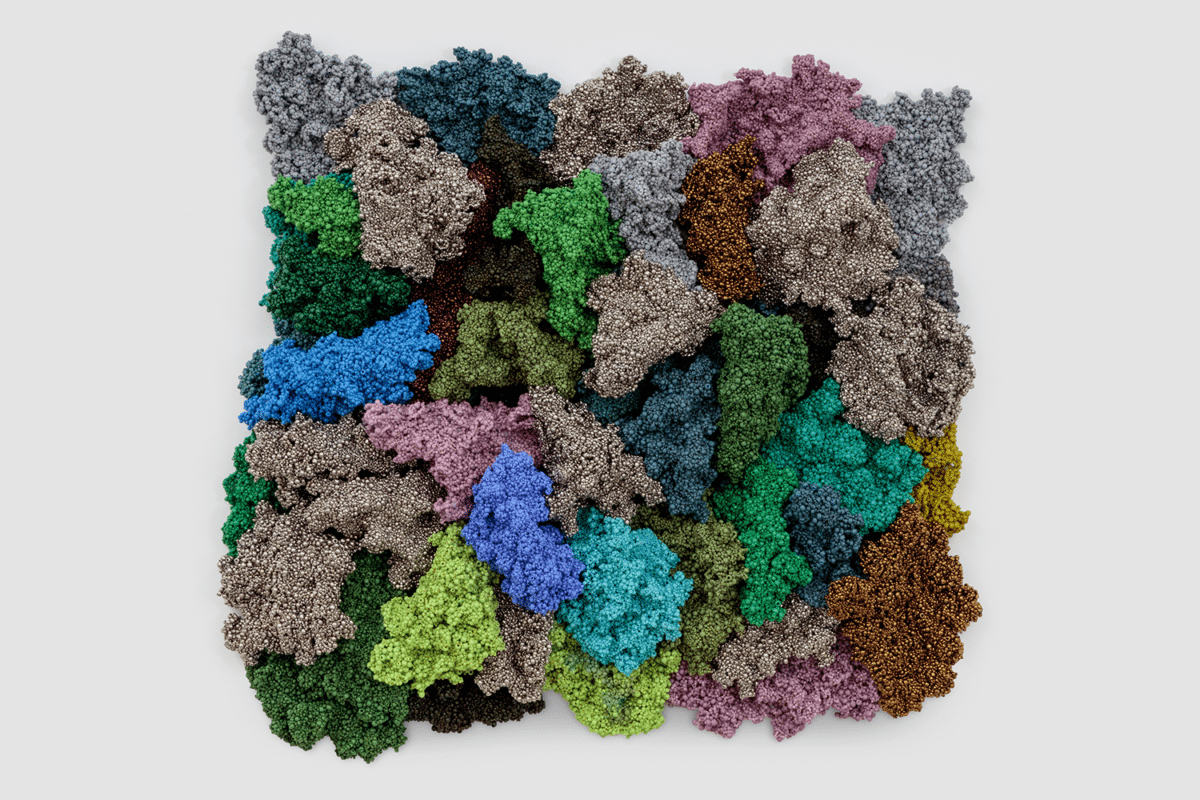

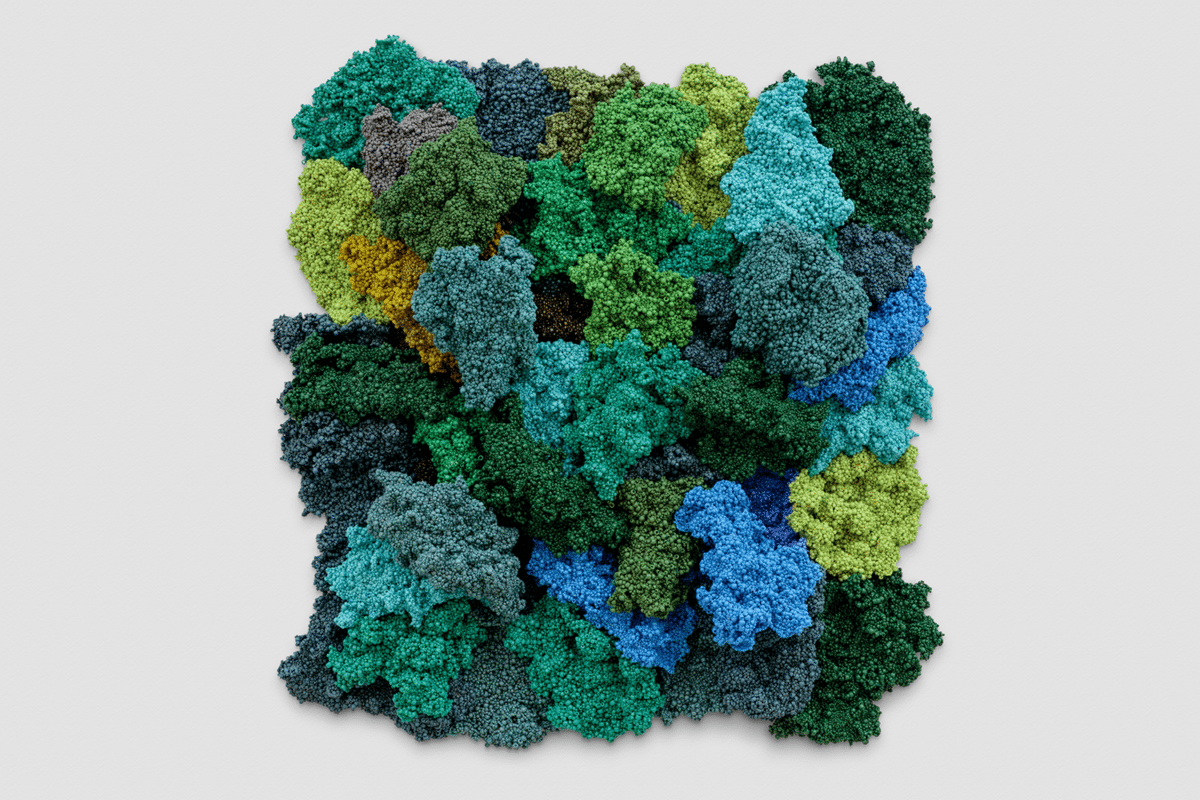

- Lichenform III, 2018. Woven glass beads.

- Lichenform II, 2018. Woven glass beads. Photo by Joshua White

During a walk-through of Lou’s show, a man with thick glasses asked a series of questions that seemed to upset her more and more. Are the women who work in her studio single? He wanted to know. Was it true that 90 per cent of women in the township have Aids? When he said that, Lou rocked back on her heels as if she’d been slapped. “That man really pushed my buttons,” she told me the next day. “He really, really, really did. Health is a real issue for the women I work with, but the way we treat it is that everyone has HIV, including myself—there isn’t a separation between me and you—we all have disease in one way or another.”

Much of the work in Classification and Nomenclature of Clouds represents Lou’s desire to bridge the distance between herself and the women in her Durban studio, exploring both community and labour. While creating the beaded cloths, each assistant left traces when oil from her hands subtly darkened the beads in places. Then Lou altered the beaded cloths in various ways, painting, smashing and mending them. In Nacreous (2018) she layers a grid of cloths within a frame. Glimpses of pink and blue paint show through, resembling clouds floating against a sunrise.

- Lichenform I, (detail) 2018. Woven glass beads.

- Lichenform I, 2018. Woven glass beads. Photo by Joshua White

“Health is a real issue for the women I work with, but the way we treat it is that everyone has HIV, including myself—there isn’t a separation between me and you—we all have disease in one way or another”

For Lou, adding layers of paint on top of these marks represents a sort of communion. “It was a way to continue to hold hands across the miles,” she says. “Every time I painted on top of a beaded panel I was saying hello to the woman who made it.”

Classification and Nomenclature of Clouds

At Lehmann Maupin, New York, until October 27

VISIT WEBSITE