If you go down to the gallery today, you’re sure to see… yourself. The collective hand-wringing over the filter-happy “selfie generation” doesn’t bear repeating, but what is interesting about this new mode of self-interest is the way it’s moved way beyond our phones/sneaky hand-mirrors and into the art world. Not content with seeing ourselves reflected back in screens, it seems we’re increasingly hunting for our own image in artworks, too.

I’ve long had a hunch that Instagram—that window-display of all that’s so cool and interesting about us—has had a direct impact on the sort of work that people are most willing to go and see. Subtlety doesn’t cut it like, say, a room full of balloons and static-haired people does (Martin Creed’s 2014 What’s the Point of It?). Quiet works don’t make for as playful, “look-I’m-having-fun! And culture!” Insta-missives as a room full of massive mushrooms and little touchable red and yellow pills (Carsten Holler’s 2015 show Decision); or a vast Katharina Grosse work; or the sumptuous enveloping reds of installations such as that from Chiharu Shiota currently showing at Blain Southern. Such huge, snap-happy exhibitions can sometimes feel like the art-world freakshakes of our day: spilling over with cream and froth, instant saccharine gratification that’s fun for a minute, but very soon terribly sickly.

“Subtlety doesn’t cut it like, say, a room full of balloons and static-haired people does”

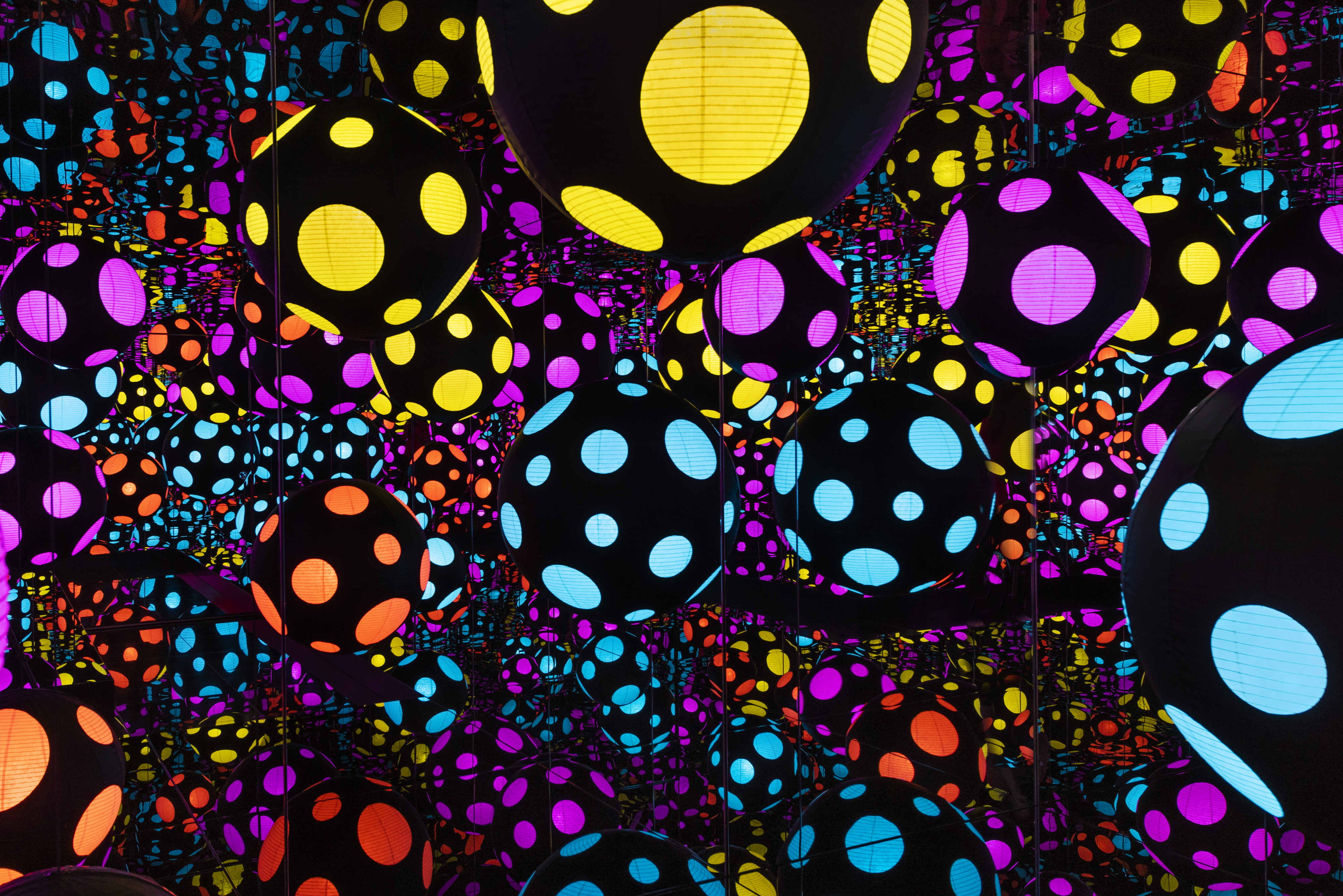

This isn’t to suggest that artists are deliberately creating work to fit into the squares of an image-sharing app. Of course, many of these pieces were conceived long before such platforms existed. The most oft-cited art-for-the-’gram is almost definitely that of Yayoi Kusama. Her iconically infinite, spotted works are so seized upon by the photographing masses that the queues for her exhibitions are now as legendary as the pieces themselves—something satirised beautifully by illustrator Jon Burgerman, who created his own “infinity box” out of cardboard to offer those queueing for a Kusama exhibition in New York a chance to get the selfie without having to actually bother waiting in line to see the show IRL.

It’s sort of preposterous that it’s come to this, when you think about—especially in an age of (albeit often surface-level) urging for us to “speak up” about mental health. Kusama has long been frank about her pieces being manifestations of her mental health problems: she has frequently stated that her art “originates from hallucinations only I can see,” which are then “translated” into paintings and sculptures. “All my works in pastels are the products of obsessional neurosis and are therefore inextricably connected to my disease,” she says. Yet today, they’re little more than theatrical sets in which we art-direct ourselves and our loved ones; backdrops for our own vanity and pleasure.

And while it’s not so much the artists making works deliberately to feed our Instagram-gratifications, it perhaps isn’t a stretch to suggest that galleries and art fairs are very much playing on what they know to be “shareable content” in choosing what they show. Gallery art fair stands know they’ll get the most snaps with big, bold retina-delighting colours; or better still, reflective works in which we can both take a subtle selfie, and broadcast to the world we’re very much looking at art, or at least standing near it (probably a nice shiny Anish Kapoor).

Because while our feeds demand bombast—big, bright works for that all-important cutting through of digital noise—they also demand faces. It’s long been established that the magazine covers that sell best are those that make “eye contact” with us on the shelf, and as such, it’s likely that the images on social media that make the most impact are where we, too, make eye-contact with our unseen hoard of followers and story-watchers.

“Where do we draw the line between art and good old-fashioned dicking about?”

It’s obvious to look at the big, shiny art as emblematic of this new-fangled narcissism—especially when such works are by the likes of the king of LOOK AT ME, Jeff Koons. But it’s not just reflections that incite us to raise our phones aloft, tilt our heads and scan the walls for the appropriate exhibition hashtag. It’s the playground feel of it all, or art that very blatantly broadcasts just how much fun we’re having (lots, natch). In today’s Groupon-fuelled world of “immersive experiences” and a collective desire to return to the simpler pleasures of childhood (frappuccinos, Escape Rooms, dressing up as someone from Top Gun to go and watch the film somewhere otherwise unremarkable in the Docklands), it’s little surprise we see the art world echoing such pastimes.

Where do we draw the line between art and good old-fashioned dicking about? There’s nothing wrong with the latter, of course, but it does complicate things. Take The Beach, for instance, by Snarkitecture. It’s a massive ball pool. How then does that differ from your average suburban soft play area? Just because it’s an “installation”, by name, and the balls eschew gaudy rainbow brights for tasteful, minimal white?

Perhaps it’s just coincidence that the current show at the Hayward Gallery, Space Shifters, seems designed to appeal to our collective inner Narcissus. The group show gathers works from the past fifty years created largely in translucent materials such as glass, acrylic and polyester resins and those with reflective surfaces, such as stainless steel, polished bronze and engine oil. “Luscious and seductive—and often demonstrating huge technical accomplishment—these objects act as optical devices that enable us to see our surroundings in new and unexpected ways,” reads the show blurb. Of course, we see ourselves in new ways too, shining out from those works—and more than likely, in due course, shining out from our social feeds, too.

I was wondering why we have this sudden need to see ourselves anew, constantly; but maybe the situation is more a chicken and egg one. Galleries show work that insists on showing us to ourselves, so that we in turn show the work to the world. In a climate that often prizes “reach” and “engagement” over real, considered looking and actual, thoughtful engagement with work (especially in the sphere of public galleries that must cater to a broad audience), maybe we shouldn’t be too quick to judge institutions’ decisions to openly present pieces that cater for the Insta-generation. But surely, one day not far in the future, we’ll at last be sick of the sight of ourselves?