Wandering through Ian Sinclair and Loren Kronemyer’s 2016 Ecosexual Bathhouse, which was housed in multiple locations around the world, guests encountered many surreal sights, sounds and, if they wanted, sensations—from being showered with pollen to misting with a strap-on plant spray—as they were invited to play with plant-based toys, watch eco-porn, and dance with the “resident metamorphosing mistress”. They were encouraged to have consensual, mutually beneficial relations with everything from compost to the wind, and to be transported into a world where cress-sprouting face masks and floral ball-gags disrupted the boundaries between the human and non-human, the personal and the political, and the intimate and the environmental.

Plants, especially flowers and fruit, have been associated with both the quasi-spiritual magic of fertility, and very earthly sensual pleasure for as long as people have been able to think allegorically. For a long time they were even thought to have a kind of sentience, to have feelings and agency, and to be active participants in holding creation together at the seams—seams which, to the medieval mind, were inherently prone to fraying. Today, as the seams of creation tear dramatically all around us, philosophers and eco-theorists like Timothy Morton are increasingly turning back to theories of non-human ethics, and considering the agency of inanimate objects, of animals and environments, as we all look for ways to build a healthier relationship with Earth.

“Ecosexuality combines avant-garde queer theory with radical environmentalism, and the result is something that has the capacity to shock even the radicals from whose work it descends”

- Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle, Dirty Sexecology. Performance. (Left) Calderwood Pavilion, Boston, November 13, 2009. (Right) Vienna, March 5 & 6, 2010. Courtesy of the artists

Of course, there’s a fairly obvious way to build a healthier relationship with Earth, and that’s to do it quite literally. To treat Earth not as a mother from whom you are entitled care and support (and whose fridge you raid unthinkingly), but as a lover, who has every right to leave you if treated with anything less than devotion and respect. This is the fundamental premise of the ecosexual movement, pioneered by artist-activists Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle in the early 2000s. Ecosexuality combines avant-garde queer theory with radical environmentalism, and the result is something that has the capacity to shock even the radicals from whose work it descends. It is often viewed with some suspicion by both mainstream queer and environmental activists, as well as by the wider public, who are understandably wary of anything that asks if you’d like to get off with some dirt, or marry the Appalachian Mountains.

“Plants, especially flowers and fruit, have been associated with both the quasi-spiritual magic of fertility”

In the world of contemporary art, however, ecosexuality has found an eager audience. The Serpentine Galleries recently hosted Plantsex

, an event reflecting on the long and intimate relationship between botany and eroticism, featuring the work of artists like Melanie Bonajo, Victoria Sin and Dineo Seshee Bopape. The event was part of their General Ecology programme and coincided with a show of Hito Steyerl’s immersive AR installation, featuring plants and flowers designed by neural networks, arcane and occult texts on plant-based healing, and a focus on changing our fragmented relationship with our environment into something more holistic and interconnected.

The gallery followed Plantsex up with A Shape of a Circle in the Mind of a Fish with Plants, a day-long symposium on plant sentience and forms of healing mysticism. Saelia Aparicio’s animations and illustrations of anthropomorphic plants and botanomorphic people, commissioned by the Serpentine for this event, capture the growing interest in a fleshy, sensitized, vegetal “other”. The pink-tipped shoots, dancing weeds and loose, leafy limbs of her creations blur the boundaries between anthropomorphic and vegetal forms, and play with ideas of post-apocalyptic post-humanism, as well as ideas of old gods and the possibilities of ecosexuality.

- Heather Rasmussen, (Left) Untitled (Cornucopia Self-Portrait), 2016. (Right) Untitled (Three Legs and Squash in Mirror, Yellow), 2016. Courtesy of the artist and The Pit, LA

It’s not just well-established institutions taking an interest in the sexiness of plants; Cuntemporary, a non-profit organization dedicated to supporting queer, feminist, decolonial art practices, also hosted a conference on eco-criticism this spring, which highlighted plant sentience and ecosexuality as exciting new avenues for artists and theorists to explore, and ended in a performance-cum-club night of “sticky” encounters, in which “you might also come across some mystic papayas, acts of shared ecolove and ecosex, BDSM technoshamanist rituals against the current ecocide… and the sacred cleansing of our inner (yoni) climate”.

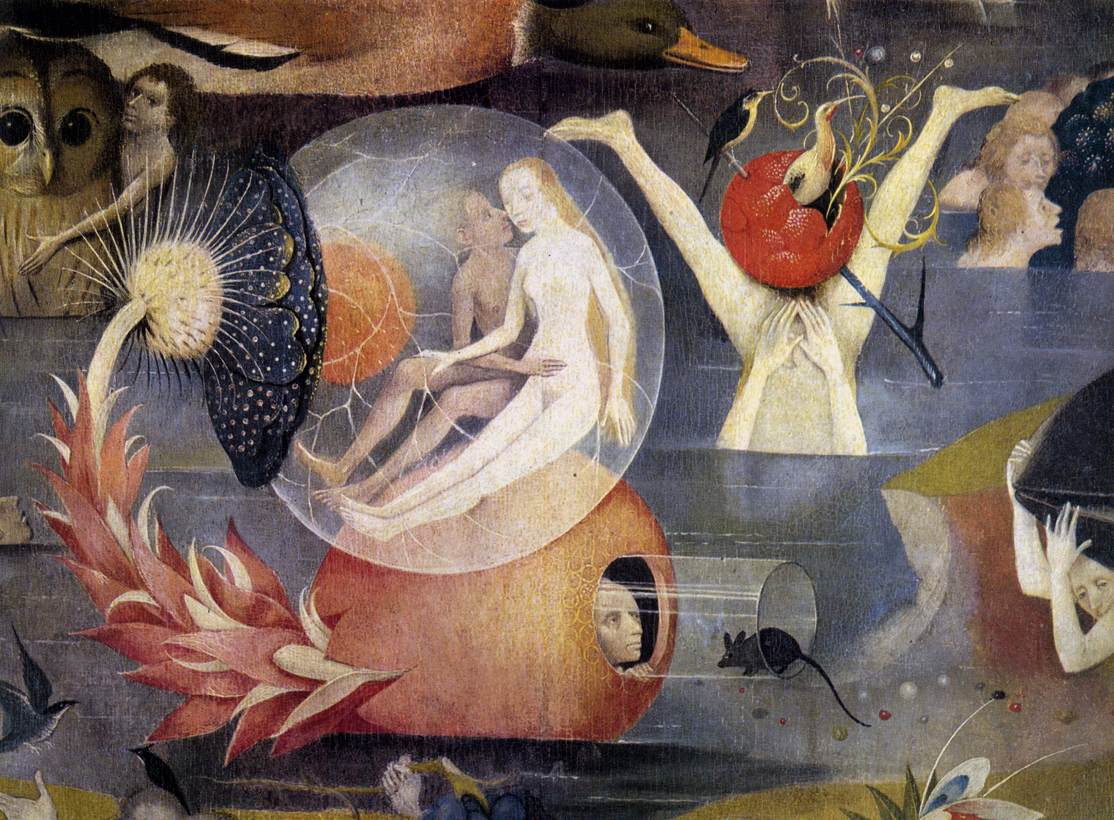

It isn’t hugely surprising that ecosexuality has found fertile ground in the art world. Art has a long history of symbolic responses to plant-based forms. Chances are anyone reading this will, at some point in their lives, have had “that” conversation about Georgia O’Keeffe’s flower paintings. You know the one. The “did she mean to paint giant vaginas?” one. Go further back and there are the flower fairies of Victorian high-kitsch, or Hieronymous Bosch’s wonderful, fantastical Garden of Earthly Delights, which features couples making love inside flowers, fruit emerging from akimbo legs, and a whole host of other transgressive but utopian depictions of uninhibited, unalienated sensual pleasure. Even further back there’s the medieval illustrations of mandrakes, or the pagan Green Man motif, relics of alternative ways of seeing and being.

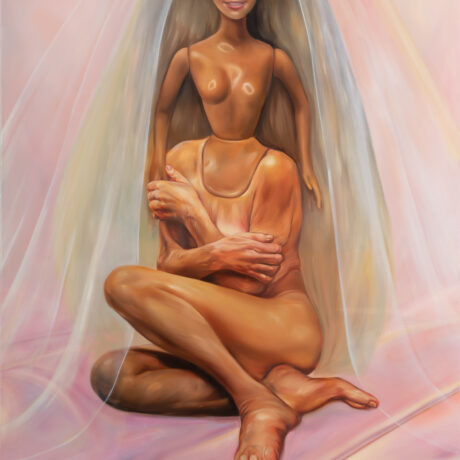

Artists have been blurring the boundaries between people and plants for a very, very long time, and the environmental crises of today are only lending an edge of urgency to their efforts to transcend distinctions between nature and artifice—between animals, vegetables and minerals. It’s a concern that reaches further than explicitly environmental work. When Heather Rasmussen plays with the aesthetic and sexual qualities of her own body—disrupting predictable four-limbs-one-head forms with mirrors and plaster casts, but retaining the sensual qualities of a sinuously curved and pointed foot and introducing bulbous, fleshy squashes and other coiling vegetable forms—she highlights the capacity of sensual aesthetics to both rupture and form connections, and questions the underlying conditions of her own physical existence.

What happens if we don’t break down some of the boundaries between human and non-human, between self and other? In Hito Steyerl’s Serpentine installation, “future” plants bloomed and mutated before our eyes like an accelerated, disturbingly intangible re-interpretation of an O’Keeffe, vulnerable and unstable in a future where the rules of reality have been undermined by human exceptionalism. They are plants which have been “gaslit” by humanity, worn thin and lacking the solid, earthy sensual presence that has traditionally given them their magical, spiritual and medicinal qualities.

Fundamentally, ecosexuality seems to be an attempt to understand and disrupt the alienation from nature which leads to such abuse. That’s an itch that art has a long history of scratching, so it makes sense that the possibilities of this radical, queer, environmentalist ideology should be having a moment in a world practically built on the problems of image vs reality, self vs other, and artifice vs nature.