What’s scarier: witnessing a serial killer robot methodically mop up blood at this year’s Venice Biennale, or the FOMO of skipping the art world’s most hyped event? How about this one: watching a movie about a haunted sculpture that literally devours LA’s gallery glitterati, or actually inhabiting the la-la-land of influence-obsessed art stars?

What’s the root of our fixation with body horror? As Jonathan Jones pointed out in an atypically insightful op-ed a few years back, we’ve depicted the terror of our flesh chambers for as long as we’ve been trapped inside them. Dreams of ascension and communion with immaterial deities are as old as human consciousness itself—so the prohibitive factor of embodiment has been poked at, prodded and dissected as surgeons do with scalpels. The results are often shockingly gruesome. But what about horror in contemporary art?

“The best kind of horror always creates an ambiguous mixture of feelings”

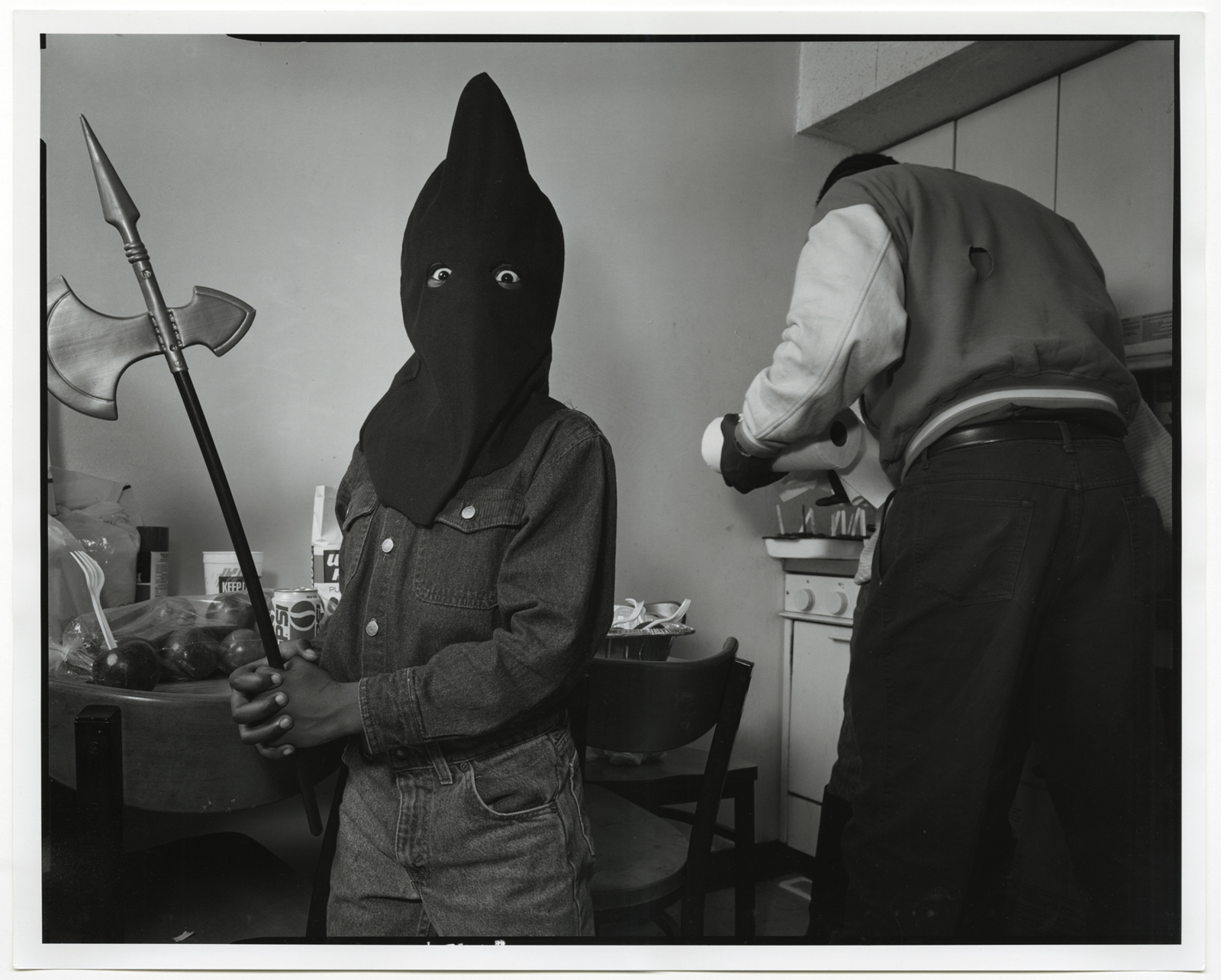

Instead of simply spilling guts and blood, today’s artists pursue darker demons. Mental illness and racial violence, the abuse of queer bodies and the toxic clutches of the privatized medical system are all far scarier than some grimacing gremlin. There’s a perverse kind of emotionalism packed in, too—artists are vindicating the monster, turning it into a tragicomic character worthy of your affection. Simply put, the black and white line of good vs evil is no longer so simple.

“The best kind of horror always creates an ambiguous mixture of feelings,” says writer Charlie Fox, who curated the goosebump-raising group exhibition My Head Is a Haunted House, which is currently on show at Sadie Coles in London. “It’s not slasher gore, but something that creeps over you slowly, a sinister but delicious feeling… it puts you inside the monster’s skin, and the world never looks the same again.”

Interlacing opposite ends of the horror spectrum from Sue de Beer’s inexplicably weird Making Out with Myself (1997) to Alex Da Corte’s hilariously endearing Slow Graffiti (2017), Fox conjures a fun home of spooks big on love, empathy and desire. Going deeper than surface level scares, the exhibition becomes a parallel universe of slow-burn spookiness: De Beer and Marianna Simnett use uncanny and comical aesthetics to tease out questions of bodily autonomy. But the show also gives into its own theatrics: devised as a carnival, the installation is drenched in purple and green light, adopting a melodramatic aesthetic that’s complete with a gift shop of monster masks.

My Head Is a Haunted House offers an excellent taster of contemporary horror’s many terrifying tendrils, but in order to understand how horror entered the contemporary art world, we must travel back to 1980s Amsterdam. In March of 1986, a painter named Gerard Jan van Bladeren walked into the Stedelijk Museum and attacked Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III (1967) a painting by Barnett Newman that was infamous for provoking a sense of existential dread among visitors. He slashed it with a boxcutter. Stretching 5.4m long, the crimson canvas was slashed eight times, putting an end to its reign of terror.

“Instead of simply spilling guts and blood, today’s artists pursue darker demons”

The butchering of Newmann’s canvas within a supposedly sanctified institutional space shook the art world to its core, and in the process, it opened up a new platform for high visual culture to invoke horror. More significant still, the painting’s violent destruction symbolized the changing relationship between art and its audience in an age of increasing uncertainty. Since then, globalization boomed, walls and empires collapsed, the Internet reared its digital head and the first qualms of climate change began to surface—the terrifying performances, spooky installations and mind-bending videos keep coming.

- Mike Nelson, The Coral Reef, 2003 © Mike Nelson, courtesy Matt’s Gallery, London

At the end of the millennium, British sculptor Mike Nelson’s The Coral Reef (1999) turned the architecture of globalization into a highbrow house of horrors. Conceived as a series of rooms originally installed at Matt’s Gallery in London, the installation conjured a similar sense of existential unease in its visitors. Narrow corridors and claustrophobic rooms exposed the crushing effect of global capitalism: scenes of urban squalor revealed the art world’s privilege in it all and made visitors complicit in this cannibalistic food chain.

The real knife twist comes from the work’s ironic title that elevates abject poverty, when displayed in the white cube, to the exotic and (no longer) life-giving world of coral reefs. The message implied by The Coral Reef chimes with the 2017 spoof film The Square: that the art world is a debased villain guilty of grotesque indulgence and aestheticizing violence, but the fact that we still indulge these hackneyed and problematic platitudes as unavoidable grievances of art culture’s operating logic might as well reveal us to be the true monsters.

- Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Can’t Help Myself, 2016. Mixed media. 58th International Art Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia, May You Live In Interesting Times. Photo by Francesco Galli, courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

One of the most popular works at this year’s Biennale, Can’t Help Myself (2016) by Chinese artist duo Sun Yuan and Peng Yu seems to suggest as much. Inside a room-sized glass box, a serial killer robot methodically mops up the blood pool of its latest kill. Thick ruby liquid slowly bubbles across the floor, but it’s always reigned in by the machine before it trickles too far; everything’s under control, nothing to see here, suggests its nonchalance. Equal parts horrific and soothing, visitors found themselves listening to their inner demons and yielding to the spectacle.

But make no mistake, the monster can definitely still be the artist. The American artist Jordan Wolfson shook the art world in 2016 with Colored Sculpture: an animatronic red-haired, maniacal-looking puppet tethered in chains and repeatedly stretched, twisted and slammed against the gallery floor. The character is apparently imaginary, “like a cross between Huckleberry Finn and Howdy Doody”, claims its Frankenstein creator, but as it takes more beatings, its face grows less recognizable.

“Tate’s Board of Trustees wouldn’t have lasted two seconds in Velvet Buzzsaw”

The puppet’s piercing blue eyes are video screens with special glass lenses, so it can detect viewers and make eye contact while it’s being abused. Yes, it reveals our inner demons and fixation with violence, but the work also demonstrates the art world’s refusal to be held accountable for its at times debased horror addiction. Wolfson has denied claims of any political and racial implications made by the sculpture (particularly set off by the work’s title); instead, in his quest to aestheticize violence, the weight of that discussion is forced upon the audience.

As the redhead is dragged around in front of you, the true horror of the sculpture is revealed, disturbing as much in its moral flight as the dollar-signed art world armature that heralds its senseless violence as provocative. Produced for upwards of $500,000 by a special effects studio in LA, it was later sold to Tate Modern following an exhibition in 2018 for an undisclosed amount. One thing, however, is clear: Tate’s Board of Trustees wouldn’t have lasted two seconds in Velvet Buzzsaw.

Not without its own controversies, horror is certainly finding its soft spot in contemporary art, producing that “gooey and velvety feeling that makes you fall in love with the monster”, as Fox says. Ambient aesthetics, existential terror, body politics and quasi-fictional narratives converge in a heady haunted cocktail that lets our demons out of the closet and into the white cube, where they can pose as our lover, best friend or mother—whatever they need to send us down the rabbit hole. Yet as the grotesque scenes of yesteryear grow closer to our present reality, perhaps that’s exactly what we need.