This April at Milan Design Week, the British sculptor Alex Chinneck—best known for his illusionistic pieces that appear to upend, fold and rip the exteriors of building—presented a trio of new works. A warehouse in the Tortona district was metamorphosed into a traditional Italian palazzo, with a weather-beaten facade and graffiti-splattered shutters. From the top right corner, this imitation frontage appeared to peel off as if unzipped, with the palazzo’s quoins serving as a zipper’s teeth; a plain white aperture behind glowed with pale light. Inside, Chinneck unzipped a wall and a section of the floor, both of which revealed eerily glowing fields of coloured light.

Exhibited solely for the duration of design week, Chinneck’s works were ambitious in scale, the result of ten weeks of labour. They were commissioned by, and for, IQOS—a brand of devices that heat small sticks of tobacco, providing a potentially less harmful way for smokers to imbibe nicotine. IQOS is a branch of Philip Morris International (PMI), the world’s largest tobacco company, and Chinneck’s installations were exhibited as part of IQOS World. “Through this collaboration,” Frederic de Wilde, PMI’s EU region president, explains to me over email, “we challenged ourselves and visitors to unzip conventional thinking to reveal a better, positive future—brought to life through an artist’s interpretation.”

- IQOS World Revealed by Alex Chinneck at Milan Design Week 2019. Photo by Marc Wilmot

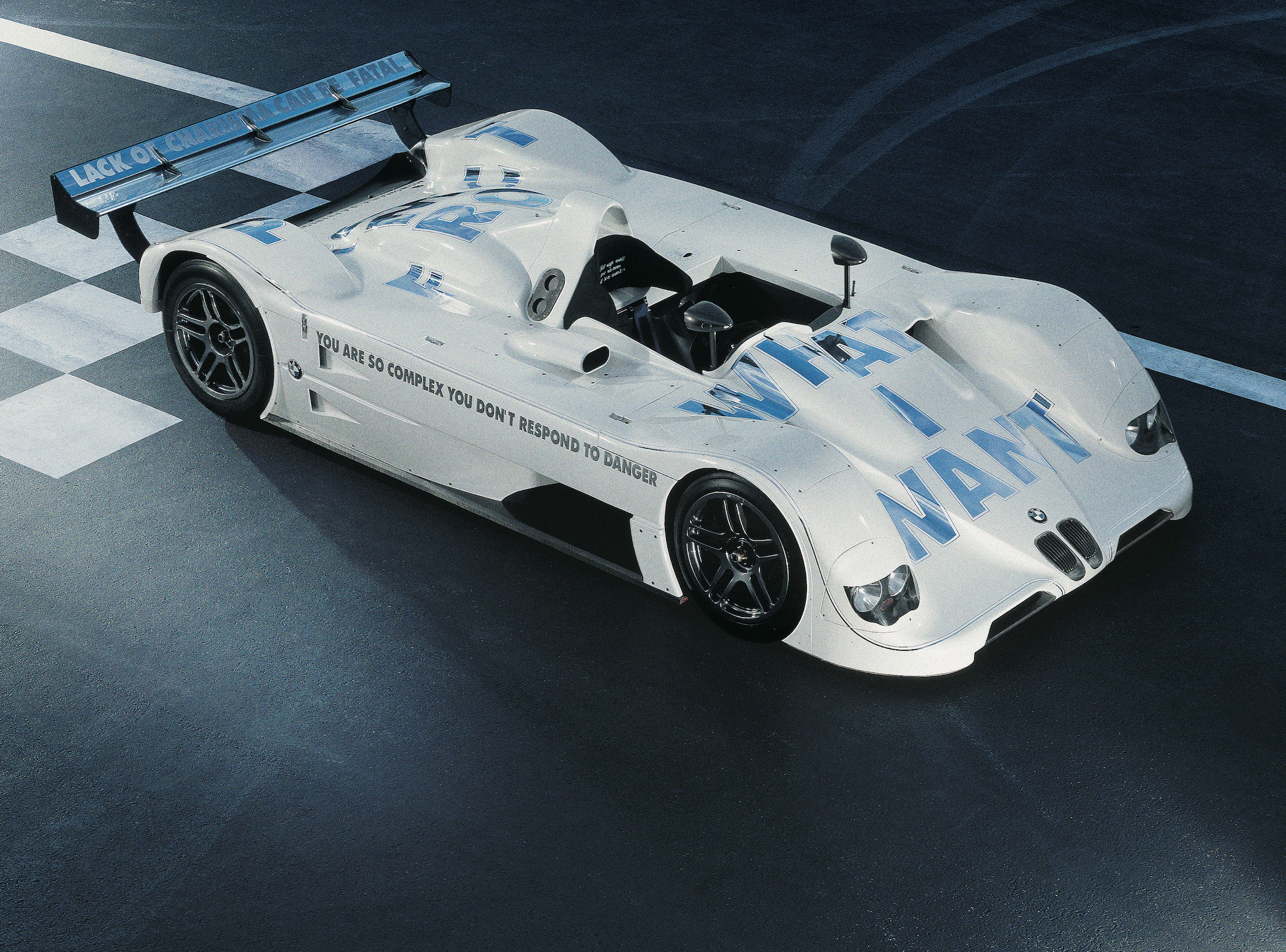

Corporate sponsorship in the arts is nothing new. London’s Tate currently receives support from Ernst & Young and Hyundai, and for almost twenty-seven years maintained a controversial connection with BP. The Tate Live programme is supported by BMW, and recently featured Faust, the highly-acclaimed performance by Anne Imhof. Meanwhile, BMW Art Cars was introduced in 1975 with the simple aim of inviting artists to use a car as a one-off canvas; their first collaboration was with Alexander Calder, and it has since expanded to include such celebrity artists as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Jenny Holzer, John Baldessari, Jeff Koons and David Hockney.

All this is hardly surprising, given that patronage is almost as old as Western art itself. What seems a more recent phenomenon, though, is the commissioning of new works primarily to be presented to the public. The prime habitat of these collaborations are art fairs and design weeks, where the creative intersects with individual and corporate wealth. As well as IQOS World at this year’s Milan Design Week, I stumbled across offerings from Google, Samsung, Lexus and Cos; I’m in no doubt there were plenty more besides. But similar partnerships have began of late to crop up in all manner of places, from Parisian department stores to the Nevada Desert.

“All this is hardly surprising, given that patronage is almost as old as Western art itself“

The pros are clear for artists, especially those like Chinneck whose pieces require a profusion of resources. Prior to Milan, Chinneck’s large-scale pieces had been largely installed in south-east England. IQOS offered a chance to appear in a new country, and to a global audience, with the backing of an enormous company. “They have facilitated work that otherwise wouldn’t exist,” says Chinneck, when I ask him about the partnership, “which is fantastic for me, hopefully good for them, and hopefully exciting to people that come and see it.” The cons, of course, stand somewhere between the ethical and the reputational: is big tobacco the sort of company to which you’d like to be attached?

From the brand side, too, the driving motivation behind these projects is fairly self-evident. At a time when digital technology has rendered advertising omnipresent to the point of overload—it is an oft-repeated adage that Americans are estimated to see 4,000 to 10,000 advertisements a day—brands need to find alternative ways to connect with increasingly cynical audiences. Collaborations with the creative fields are a potent means to achieve this, as evinced by the rise of agencies devoted to facilitating these connections. One such agency is ArtFlow. “We believe that art is a unique vector of meaning, emotion and human experience,” writes founder Katie Kennedy Perez in her 2018 report on art and branding. “As such, it has for too long been cordoned off within the walls of ‘high’ culture. Our mission is to bring artists to the heart of commercial culture.”

Art is particularly fecund for brand collaborations precisely because these walls (or cultural assumptions) appear to exist. Although in many senses commercial itself—and the so-called art world of galleries, fairs and auction houses is nothing if not the commodification of art—it carries connotations of authenticity. It can create spectacle while claiming intellectual seriousness, and still thrives on old ideas of individual creative genius. And, crucially, it retains the imprimatur of history and high culture while forming part of the zeitgeist.

One of the most visible brands in contemporary art is (the perhaps unfortunately named) Ruinart, France’s oldest extant champagne house. “We are a very old company,” says Frédéric Dufour, Ruinart’s president, “and we think that a connection to art and artists of what keeps us relevant in the contemporary. The company needs to stay active, fresh, relevant and up-to-date.”

“Although in many senses commercial itself, art carries connotations of authenticity”

Ruinart—which since 1987 has formed part of luxury behemoth LVMH—achieves this through a dizzying array of art initiatives. It partners with thirty-five art fairs, including those of the Art Basel and Frieze empires; it sponsors exhibitions in institutions such as the New Museum; it runs photography competitions; and, of course, it commissions artists (both established and upcoming) to produce new work. This month it unveiled the fruits of a collaboration with the Brazilian artist Vik Muniz, who took series of photographs of temporary plant-based sculptures for the project, to be exhibited at Paris’s former stock exchange. Muniz also created an installation for the Ruinart cellars, comprising 2,800 LED-lit champagne bottles. Ruinart is in part a lifestyle brand, pitching its products as an improving feature of its consumers’ lives. “It’s a way,” says Dufour, “to create special, shared moments.” Of course, there is a parallel to be drawn here between the functions of art and champagne.

A brand that has been particularly adept at bridging the gap between product, art and lifestyle is the H&M-owned Swedish clothing label Cos. Over the past eight years it has collaborated with a bevvy of artists, architects and designers, including an annual series at Milan Design Week. This year it commissioned the architect Arthur Mamou-Mani to create an installation of 3D-printed bioplastic bricks. Talking to Cos’s collaborators over successive years, I’ve gleaned that the working relationship between artist and brand is often highly involved and reciprocal.

“We have the benefit of our worlds feeling very similar in some ways,” says Alex Mustonen of interdisciplinary New York trio Snarkitecture, a regular Cos collaborator. “The way we look at creating our work is not dissimilar.” For a brand that sees itself as existing within the creative industries, artistic collaborations are less a leap than an easy step. “The team at Cos,” says creative director Karin Gustafsson, “is full of people engaged with art and design, and into doing research and reading about other creative disciplines.”

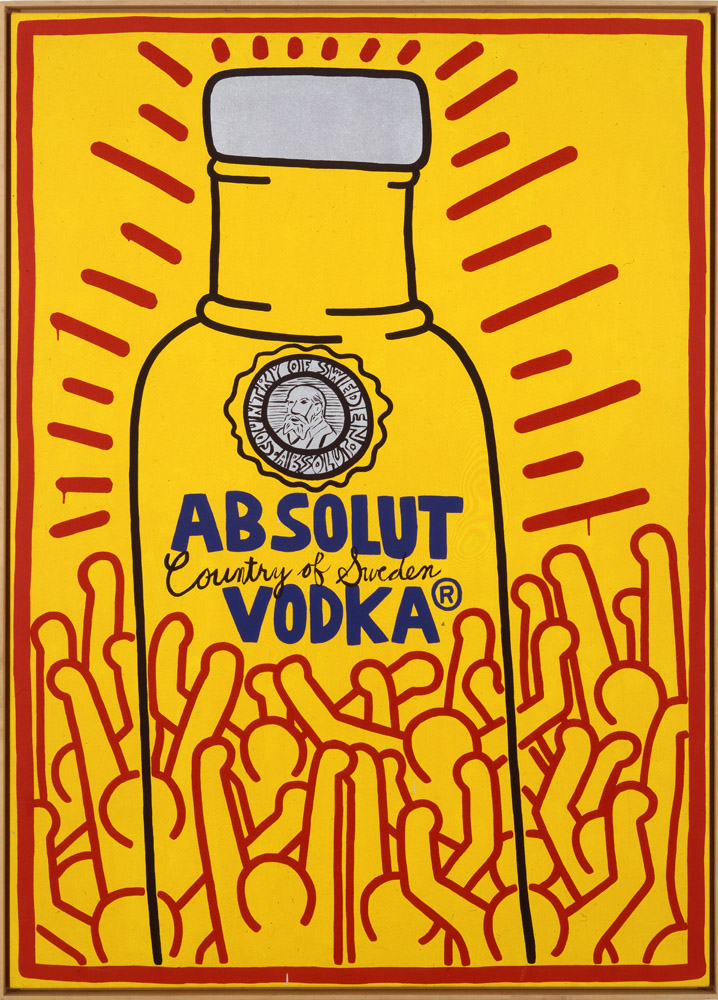

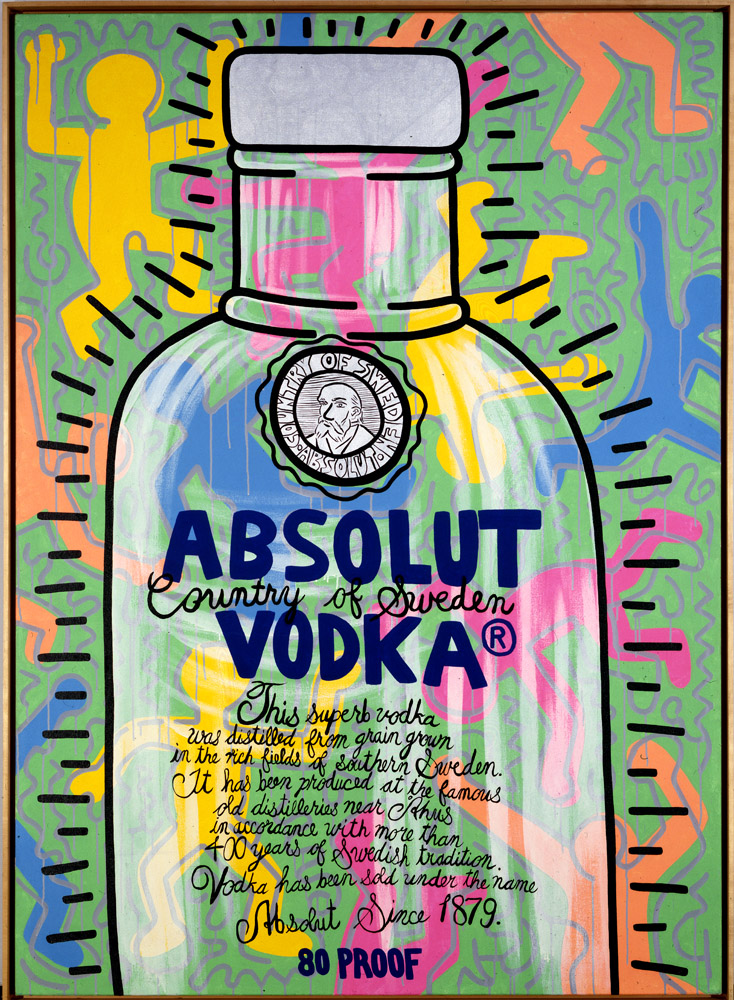

- Keith Haring for Absolut, 1986. © Keith Haring Foundation

Besides, the apparent barriers between art and brands have long been interchangeable. In 1895, Ruinart commissioned the then-unknown Czech painter Alphonse Mucha to design an advertising poster; a few years earlier, Pears Soap bought John Everett Millais’s saccharine painting A Child’s Life, which became so associated with the brand that it is now known as Bubbles. Pop Art, by testing the boundaries between high and popular culture, inevitably brought them closer together. In 1985, Absolut invited Andy Warhol to depict a bottle of vodka, inaugurating a twenty-year scheme that saw contributions from artists as diverse as Louise Bourgeois, Keith Haring and Angus Fairhurst.

“For a brand that sees itself as existing within the creative industries, artistic collaborations are less a leap than an easy step”

The Absolut Art Collection has come to be seen as culturally meritorious. In 2008, when the Swedish state sold Absolut to Pernod-Ricard, the brand’s art collection was withheld from sale as a piece of the country’s cultural heritage. It now forms part of the Spritmuseum, an independent institution that charts Sweden’s drinking culture, from medieval wine presses onwards. “It’s a very unique collaboration,” says curator Mia Sundberg, “between art and enterprise.”

Such a fate is unlikely to await the present spate of artist-brand collaborations, many of which are explicitly conceived as temporary installations, present for a brief period and then alive only in memory, Instagram and branding portfolios. Many of them are also worthy projects. And it would be churlish to deny the commitment brands like Ruinart, Cos and BMW have made to giving young artists a platform. But there remains the worry that, slowly but surely, art is sliding towards becoming a marketing accessory.