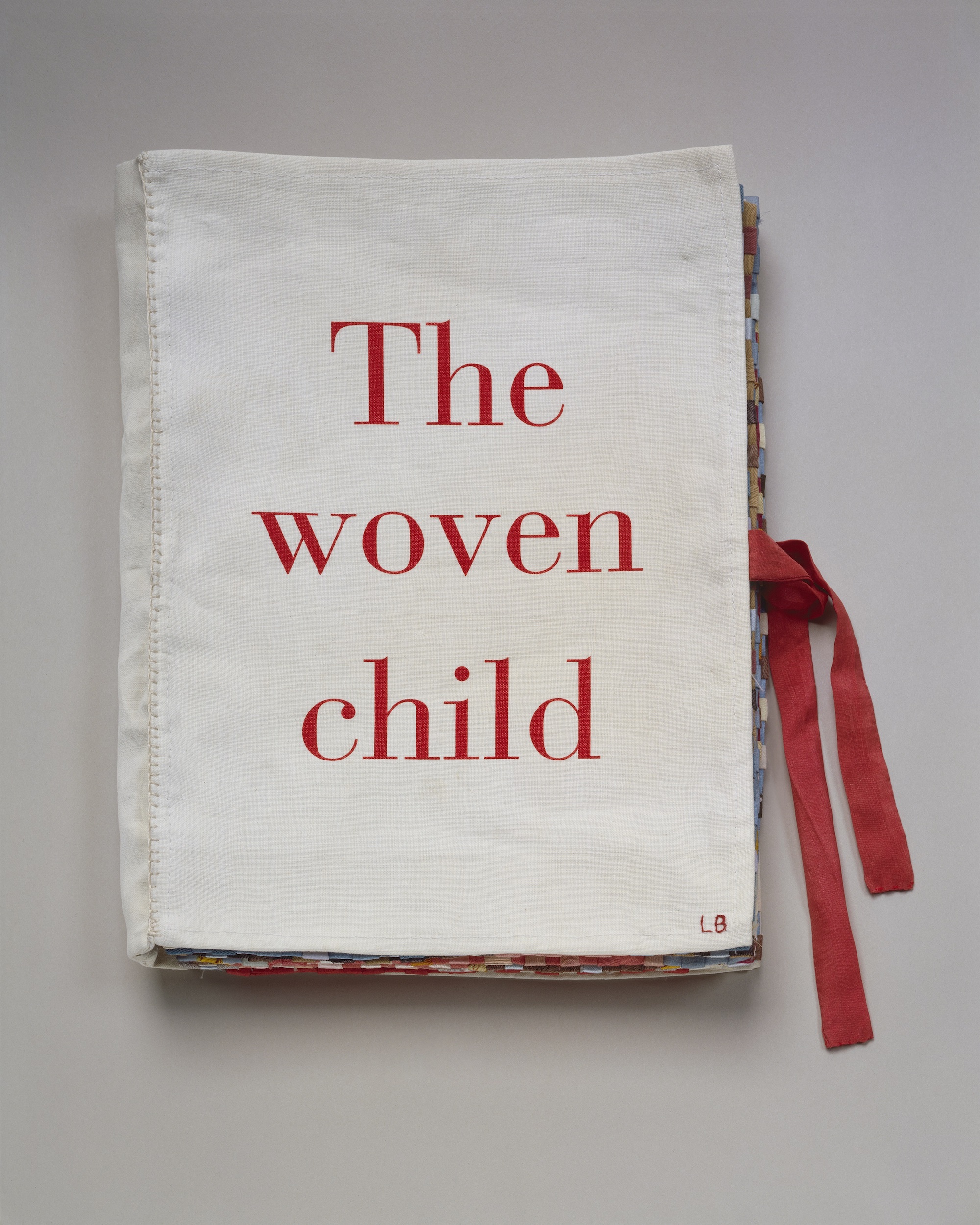

“It’s more intense than I was expecting,” a man at Louis Bourgeois’ The Woven Child exhibition is overheard muttering as he stands in front of a warped female figure formed from black fabric, twisted at an impossible angle, breasts and bulbous buttocks offered up. Two steel spikes jut upward from the figure’s feet: high heels as dainty as a Barbie doll’s, as menacing as bladed weapons. Safe and soft, it is not. Bourgeois is a virtuoso of violence. That the horror and trauma that she surfaces is buried in soft fabric only intensifies its impact.

This is the twist at the crux not only of Bourgeois’ work, but of artists all over the world who employ textiles to convey emotional intensity and political potential. They turn the expected on its head, challenging how things are supposed to be. Having been undervalued for centuries due to its associations with femininity and domesticity (and frequently relegated from the domain of ‘fine’ art to the ‘lesser’ sphere of craft) textile art has undergone a resurgence in the last decade.

The Woven Child (at London’s Hayward Gallery until 15 May) may be the first Bourgeois exhibition to focus solely on her fabric work, but it is certainly not the first of its kind. Curators at institutions across the UK and the US are highlighting various neglected traditions of textile production, from African and Black diaspora quilting to Bauhaus weaving.

One of the most prominent of these recent re-appraisals was the Tate’s 2018 exhibition of Anni Albers’ textile work, billed as “a long overdue recognition” of the Bauhaus artist’s “pivotal contribution to modern art and design”. Other artists known for their work with textiles, such as Sonia Delaunay, Judith Scott, Shelia Hicks. Magdalena Abakanowicz, Lenore Tawney and Faith Ringgold, have also received renewed scholarship in recent years.

“Textiles are able to communicate deep cultural, traditional, societal and environmental stories”

A plethora of contemporary artists are continuing to push the boundaries of what textile art can be and do. Figures like Chiharu Shiota, Billie Zangewa, Vanessa Barragão, and Bisa Butler (to name but a few), are all proving that fabric work has the power to challenge expectations and overturn conventional hierarchies, and should rightfully be regarded as a radical practice.

“Textiles are able to communicate deep cultural, traditional, societal and environmental stories,” says Los Angeles-based artist Tanya Aguiñiga. “As an art form that has been constantly subjugated because of its functionality and connections to the domestic and labor, for many of us using fibre and textile processes are acts of defiance, resistance and cultural survival.”

Aguiñiga was raised in Tijuana, Mexico, and now collaborates with artists, activists and community organisers to create installations and performances (often using traditional craft materials) that address political and human rights issues at the US-Mexico border.

Aguiñiga describes textile art as “an incredibly complex medium that many of us who have been ‘othered’ can see ourselves in”. The line between material and message, art and activism, is necessarily blurred. For Aguiñiga, working with fabric “feels like a radical act in its opposition to the norm”.

- © Tanya Aguiñiga

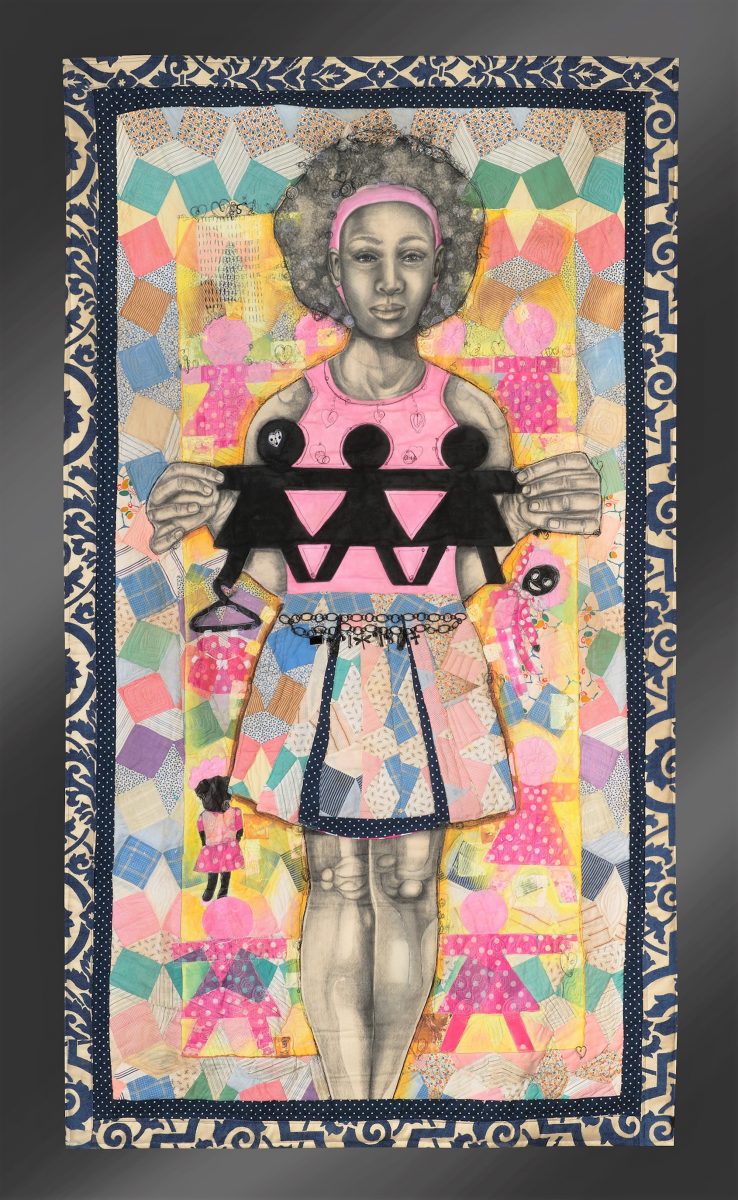

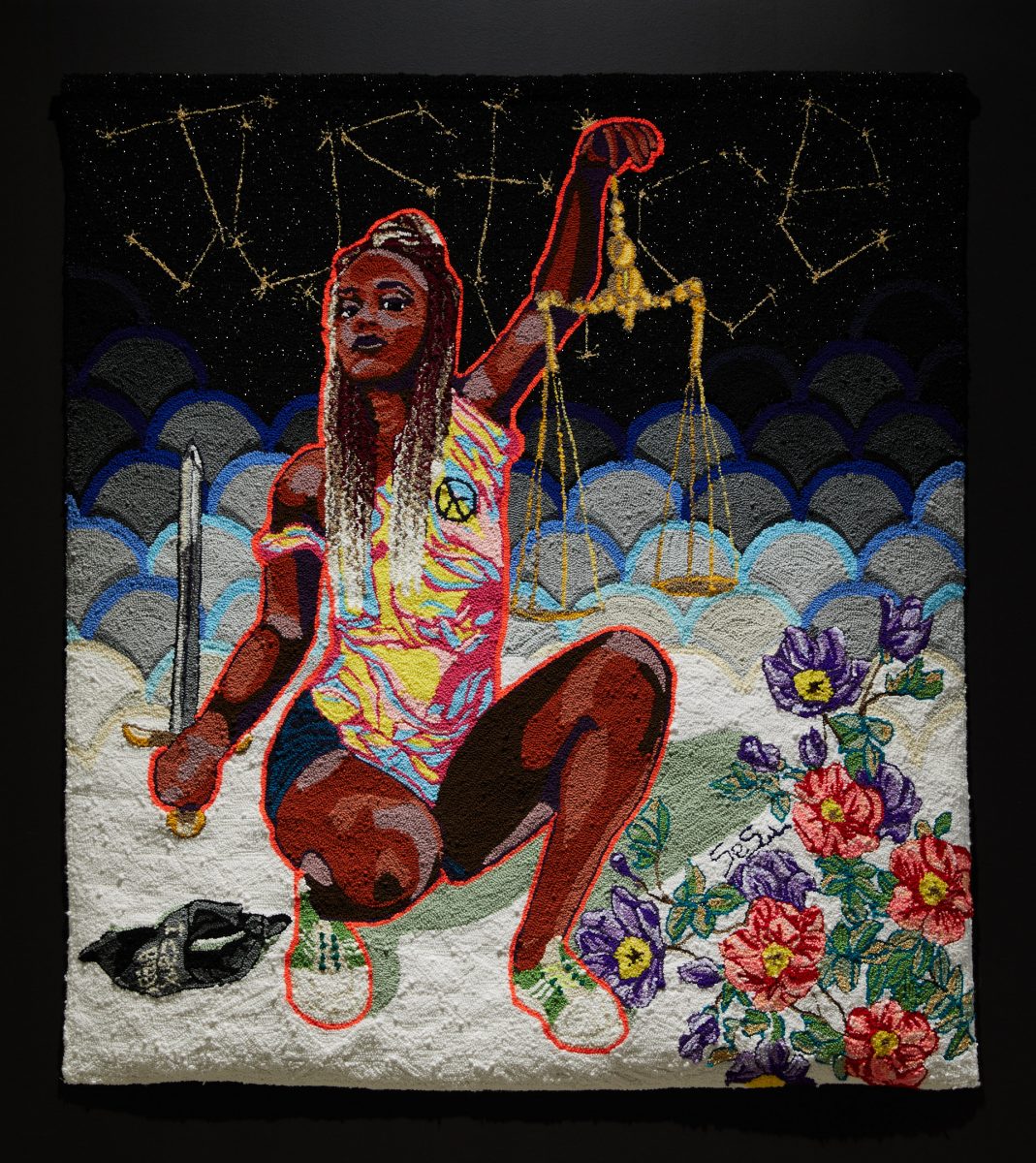

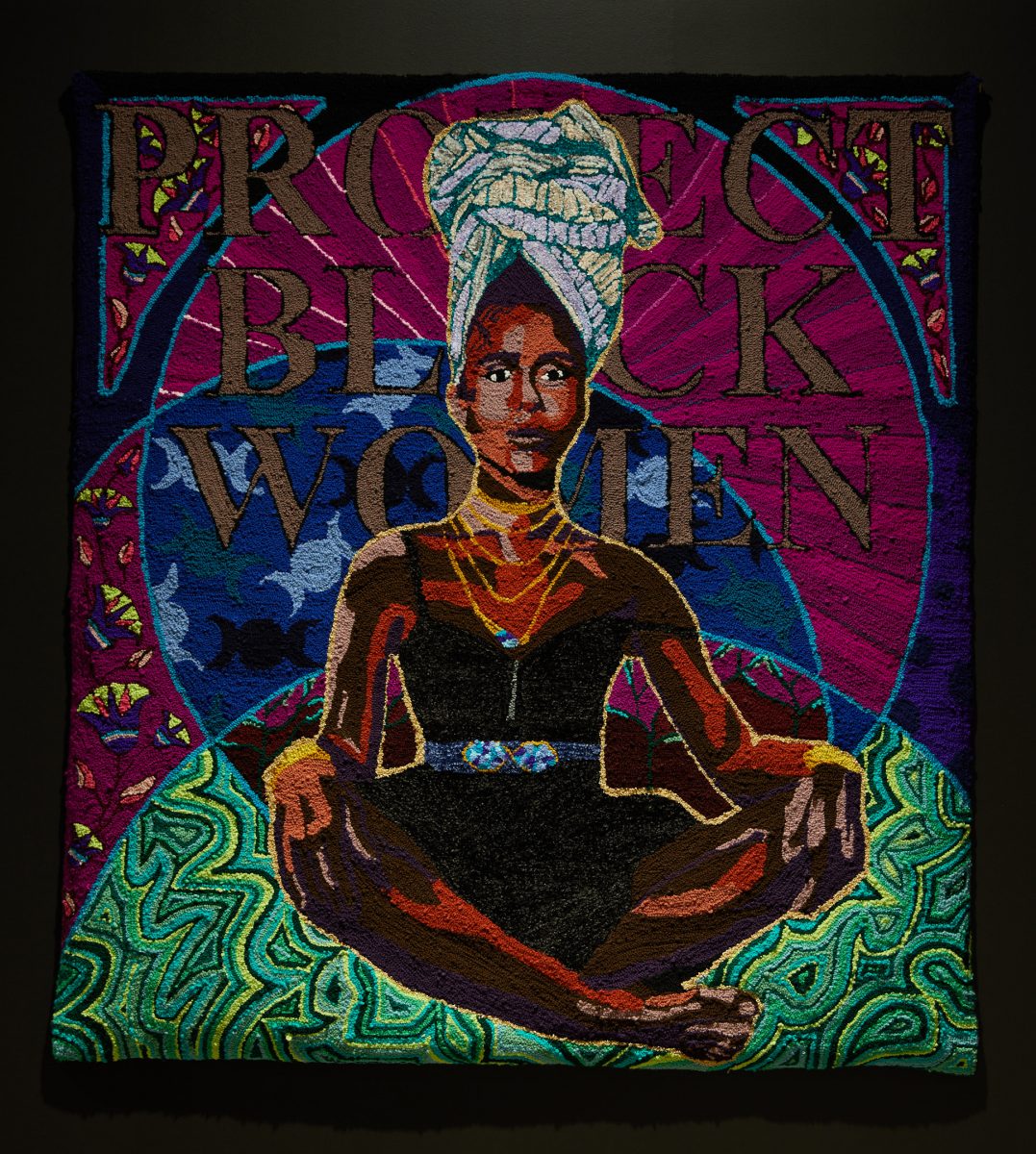

For many of the contemporary artists working with these crafts, textile processes are acts not just of resistance but of cultural survival. Simone Saunders creates bright, hand-tufted textiles that highlight motifs and iconography from her Jamaican heritage. She calls her large-scale portraiture “painting with thread.” She is acutely aware that these textiles “are often associated with domesticated crafts or utilitarian use”, and seeks to subvert that through her work.

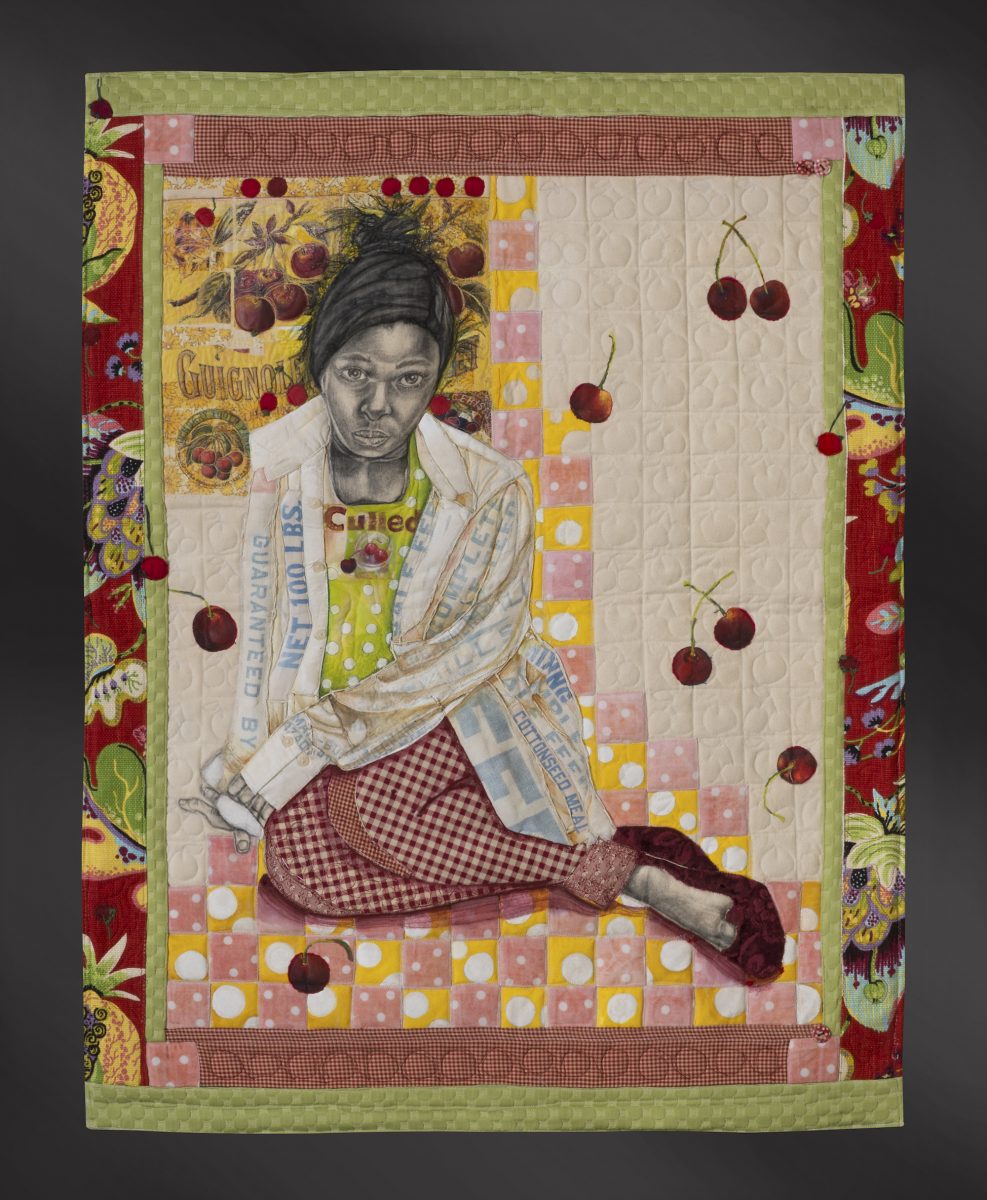

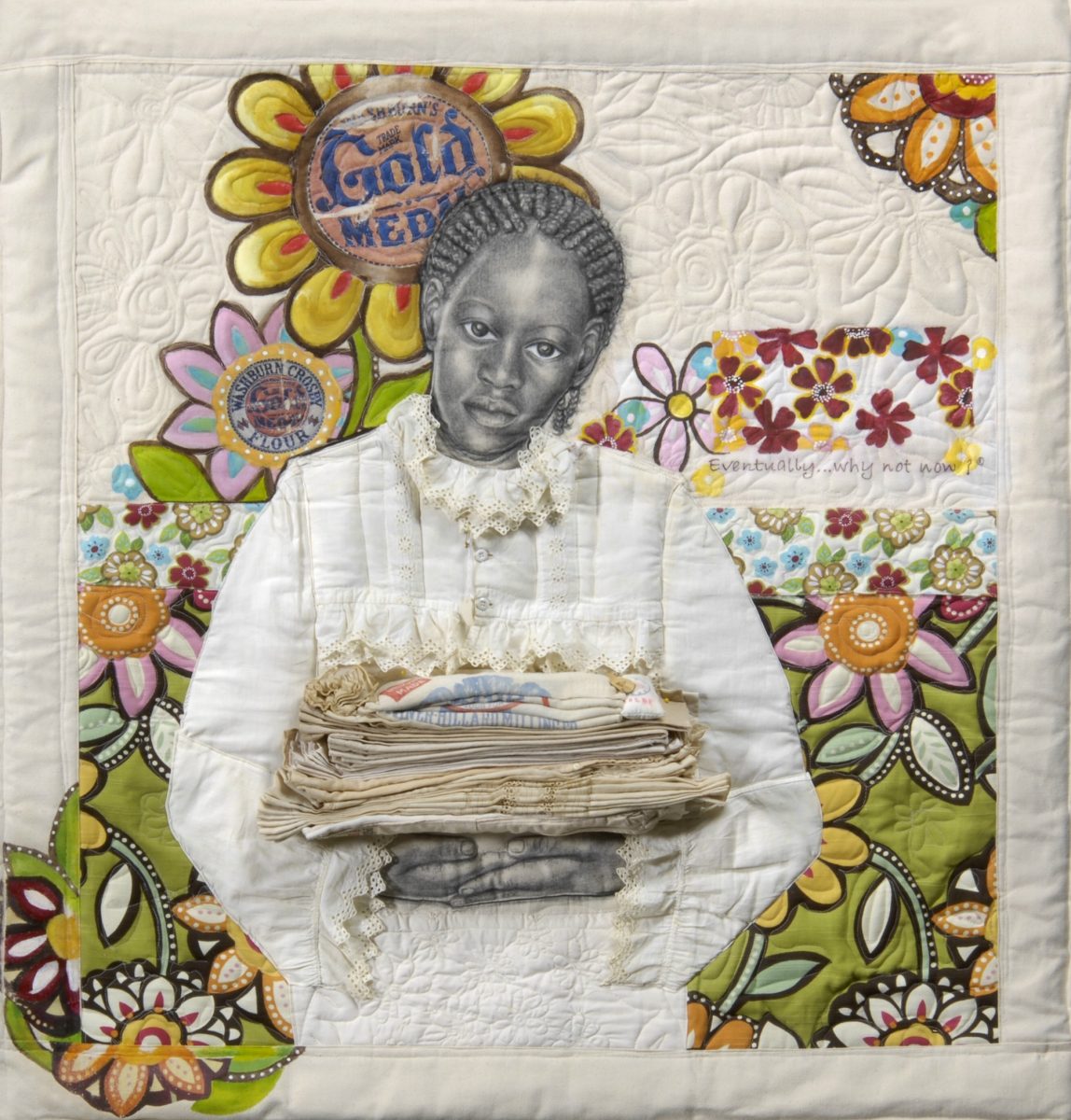

For American artist Beverly Y Smith, whose bold, collage-like quilts draw on the textile traditions of her ancestors and often focus on themes from the Antebellum South, textiles and their varied history have the power to “change perspectives, educate us about others, and change lives”.

“I have always had a fascination with the magic power of the needle,” Bourgeois once said. “The needle is used to repair the damage. It’s a claim to forgiveness.” The contemporary textile revival has seen artists both reclaim craft and its associations with the domestic and the feminine, and simultaneously shake them off entirely.

“As I mend old garments, repurpose vintage quilts… I heal from wounds my ancestors encountered years ago”

Just as Bourgeois used traditional crafting techniques to articulate complex notions of damage and psychological mending, a new wave of textile artists are currently utilising ‘domestic’ materials to navigate complex global socio-political issues, such as borders, race, colonisation, ecology, and structures of care. “For me, fibres and textiles speak of colonisation and patriarchal white supremacist structures of oppression,” Aguiñiga says.

- Left: Simone Saunders, Lady Justice, 2021; Right: She Prevails, 2020

For Saunders, “the energy and intention that goes into the intertwining of my threads is a reclamation of power and exemplifies the strength and joys of Black womanhood.” In contrast to Bourgeois, she insists that “there is zero notion of forgiveness for me, but rather a coming together of threads demanding to be seen, acknowledged and protected”.

Personal histories weave seamlessly into political narratives. English artist Anna Ray, known for her oversized assemblages and vivid soft sculpture, is informed by “the transformative experience of pregnancy, childbirth and parenting”. Ray’s mother and grandmother shared with her their love of dressmaking, appliqué, embroidery, collage, drawing and painting. Smith’s work also often contains vintage and reclaimed garments as well as nostalgic materials, while her grandmother’s quilts consisted of leftover scraps from her aunts’ worn-out dresses and uncle’s ripped jeans, and “faded floral tablecloths from several Thanksgiving dinners”.

It is a familial heritage that she connects to a deeper history of overlooked female artists. “Forms like knitting, crochet, embroidery, as well as quilting have played a critical role in women’s history,” Smith notes, “and as a means of coding information”, and Black women’s history specifically. During the 19th century, she explains, seamstresses would hang quilts in full view containing secret codes that helped slaves to escape safely to Northern states: “Each pattern led the enslaved to safe houses, food, and safe routes on their journey.”

“Working with fabric feels like a radical act in its opposition to the norm”

It could be precisely the idea of safety that gives textile art its intensity and its charge. Safe, not as in the stereotypical notion of tame, soft, cautious, or timid, but as in the removal of violence. Safety as in freedom and healing. “As I mend old garments, repurpose vintage quilts… I heal from wounds my ancestors encountered years ago,” Smith says.

Aguiñiga is clear on this: her work is explicitly “related to healing, visibility and dignity”. Working against histories of repression and violence, insisting what usually remains concealed is put on display, overturning traditional hierarchies… textile art is able to be both radically disruptive and radically reparative. These artists stitch together both violence and safety, trauma and healing.

As Aguiñiga concludes, “We are making works that we see ourselves and our struggles in. We are reshaping what is considered art.”

Eloise Hendy is a writer and poet living in London

Elephant Spring Summer 2022

Read more about Louise Bourgeois’ use of textiles in our new print issue

ORDER NOW