“Design” is a word that makes enormous and seductive promises. There is a tendency, most obvious in the tech industry, to believe that the majority of problems (no matter their complexity) can be solved with better design.

A number of designers are now thinking about what the role design might play on an increasingly hostile planet. In May 2020, at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, design critic Alice Rawsthorn and Paola Antonelli, senior curator of architecture and design at MoMa, began hosting weekly interviews on Instagram live with different designers, architects and environmentalists.

Design Emergency: Building a Better Future, compiles 25 of these conversations for posterity in a chunky blue book. The interviews circle a paradox: in making our environment more comfortable and convenient, design has also helped to destroy it.

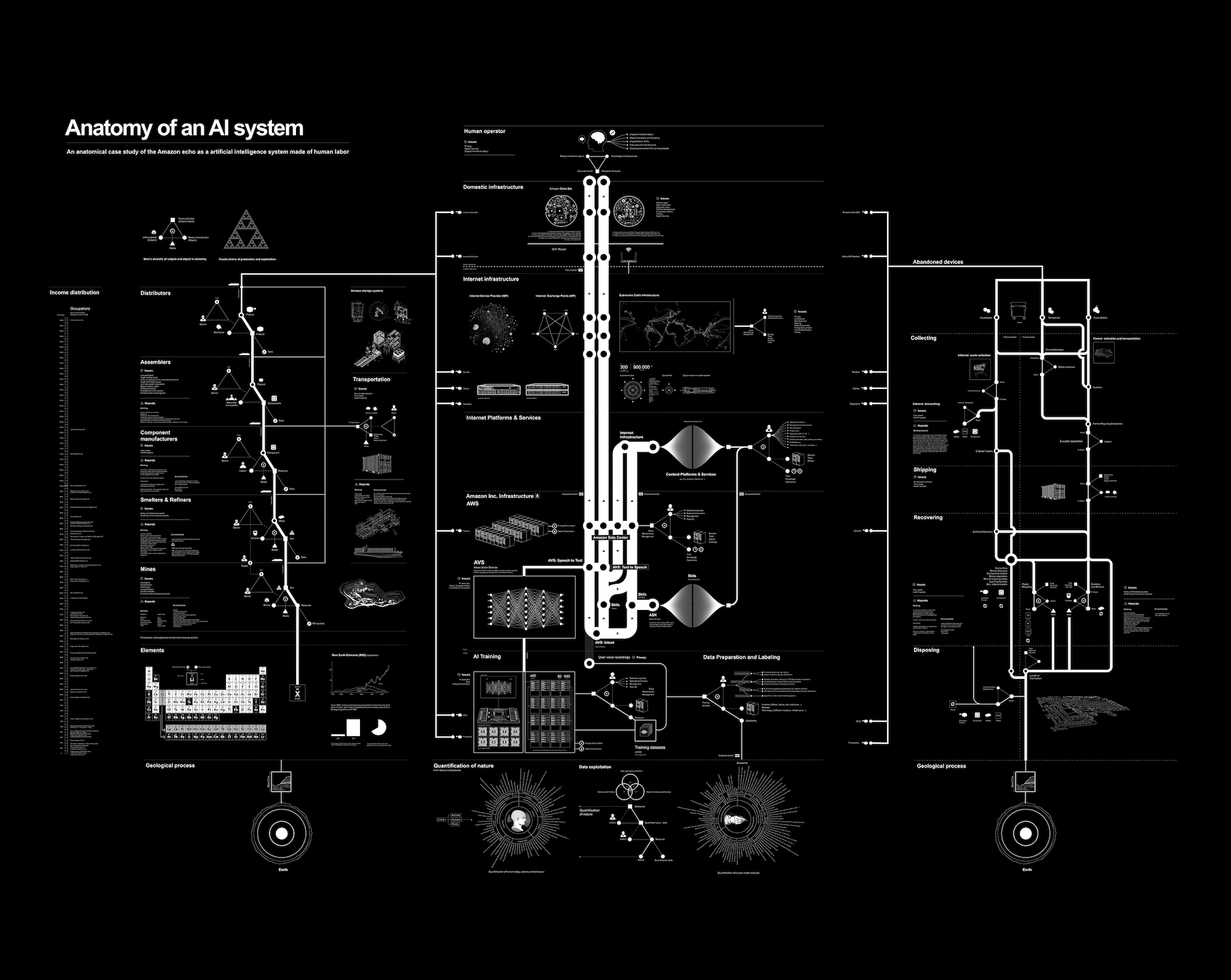

One of the most notable attempts to map the environmental impacts of digital technology is Anatomy of an AI System, produced by Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler, reproduced here in a black-and-white map. Crawford and Joler’s study traces the origins of an Amazon Echo device, from the places where its elements are mined and smelted, to its transportation and distribution, the data analysis and machine learning processes that inform its “intelligence”, and the incineration of abandoned Echo devices.

“One of my aims is to ground our understanding of artificial intelligence, quite literally, by placing it in the landscapes where it is made”, Crawford explains. Artificial intelligence is often thought of as something free-floating and immaterial, this cartographic diagram shows it to be anything but.

“It regards design less as a professional capability than a set of attitudes which can solve any number of complex problems”

“Americans love design most when we’re afraid”, the scholar Maggie Gram has observed. The ongoing attempts by various billionaires to reach and then colonise Mars are perhaps the most extreme examples of this: some people seem to believe (sincerely or not) that humans could design away their problems by escaping to another planet.

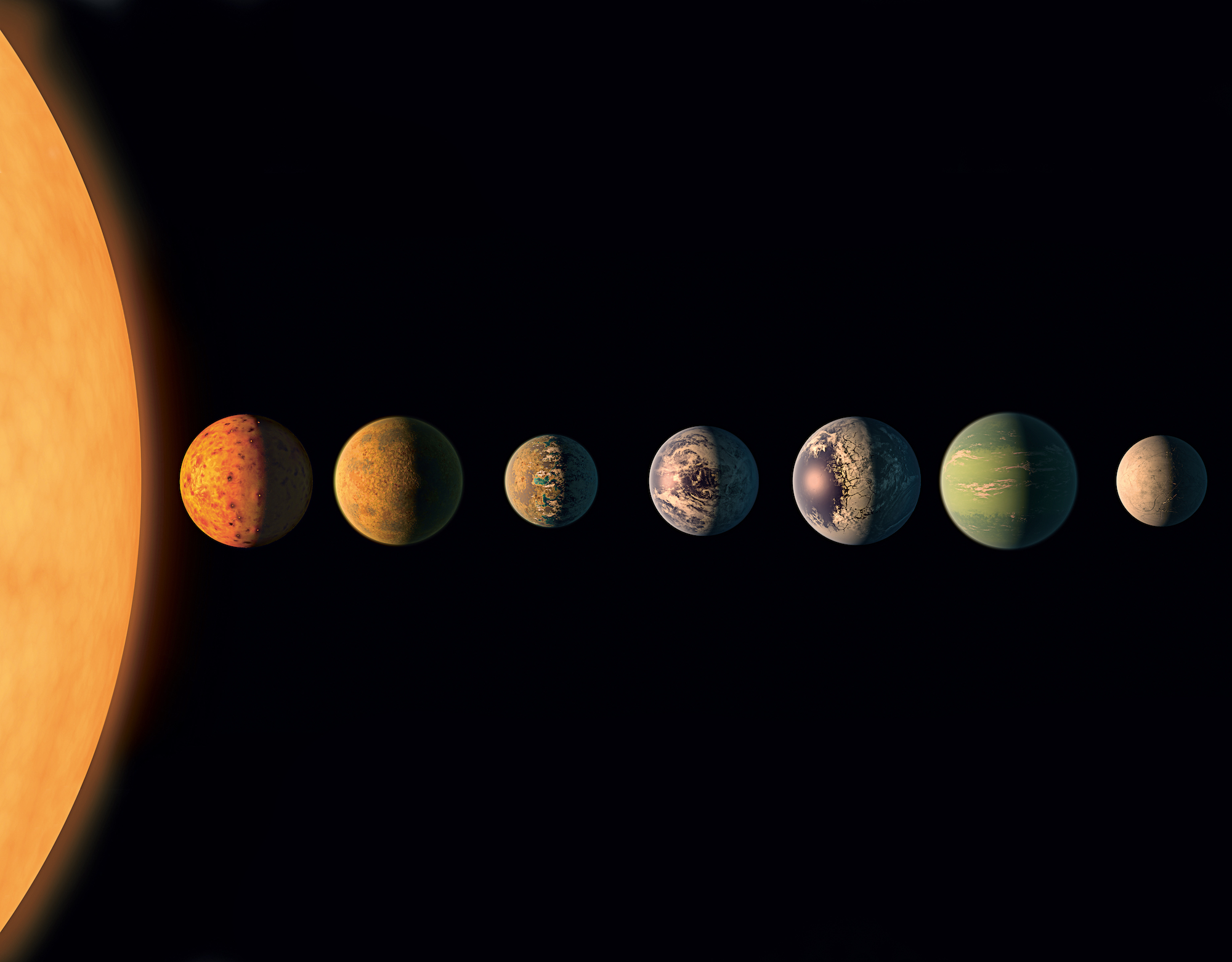

Antonelli speaks with Ersilia Vaudo, chief diversity officer for the European Space Agency, who discusses TRAPPIST-1, a solar system of seven planets with “habitable covering” identified by NASA five years ago. There could be life on TRAPPIST-1. The only problem is that it’s 40 light years away, while an average spacecraft would take 37,000 years to travel just a single light year.

It’s a shame that more space is not given here to considering whether settling on other planets is a good use of resources given the emergencies we already face on our own planet. Without seriously considering such questions, coverage of space travel feels more like vapourware for the designs of “astropreneurs” like Elon Musk and Richard Branson, attractive ego-boosts that will never actually achieve much.

Likewise the inclusion of the floating school in Makoko, Lagos, seems more like a triumph of design PR than a genuine practical solution. The school, a tent-shaped structure made from photogenic wooden struts, was widely lauded in the design press before its load-bearing structure abruptly fell apart following a storm in 2016.

Its architect Kunlé Adeyemi defends the building here as a test and a prototype. Prior to its collapse, media outlets rarely mentioned that the school was only used infrequently. Noah Shemede, the school’s director and a Makoko native, complained that the the structure was dangerous, and said that he would sometimes move desks into the school when Adeyemi warned him that journalists were coming.

Most cities are built without consideration for rising sea levels, and the architects of the future will have to “accommodate more water basins and have fewer hard surfaces”, including more drainage systems and canals in their designs, Adeyemi says. This is true, but it’s hard to see how the Makoko school is a scalable solution.

To survive on a planet which is heating up, we arguably have most to learn from projects that directly respond to their environment. Wallmakers, a Keralan architecture practice featured in the book, create homes using age-old techniques such as building with earth instead of brick or concrete, and employ passive cooling (the ability to control the internal temperature of a building without the use of AC).

“Some people seem to believe that humans could design away their problems by escaping to another planet”

Vinu Daniel, its architect founder, explains that earthen buildings use only one-sixth of the embodied energy of a normal building, and are surprisingly resilient. During earthquakes in Kerala, concrete scrapers “fell like matchboxes”, Daniel says, while many earth buildings remained standing. Wallmakers’ ‘Pirouette House’ is a geometric triumph of voluminous, twirling red bricks laid in a rat-trap technique that increases thermal efficiency and maximises ventilation.

The idea of design that Rawsthorn and Antonelli propose in Design Emergency is intuitive and spontaneous. One of their guiding lights is the Hungarian artist Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, who wrote in 1947 that design was “not as a profession but an attitude”. This notion has grown in popularity, and “design thinking” is now a buzzy phrase that regards design less a professional capability than a set of attitudes which can solve any number of complex problems.

Today, a whole industry of “user experience designers” advises companies and governments how to solve problems that have traditionally fallen outside the scope of design, such as the Universal Credit system in Britain, or the entire economy of Gainesville

, a city in Florida.

Yet approaching complex issues as “design” problems has frequently meant glossing over or doing away with politics. One original example of political engagement with grassroots design was Stuart Brand’s 1966 Whole Earth Catalogue, a countercultural manual that is mentioned only in passing here by the systems designer Adam Bly.

The catalogue’s detailed descriptions of survivalist gear foresaw a realm of “intimate, personal power” where well-designed tools could be the means of self realisation. For Brand’s acolytes, some of whom went on to found companies in Silicon Valley (Steve Jobs described the Whole Earth Catalogue as “one of the bibles” of his generation), you could change the world by upgrading the design of your operating system, without having to “do” politics at all.

If we’re to survive the next century, we’ll need to do both.

Hettie O’Brien is an assistant opinion editor at the Guardian

Design Emergency: Building a Better Future by Alice Rawsthorn and Paola Antonelli is out now (Phaidon)