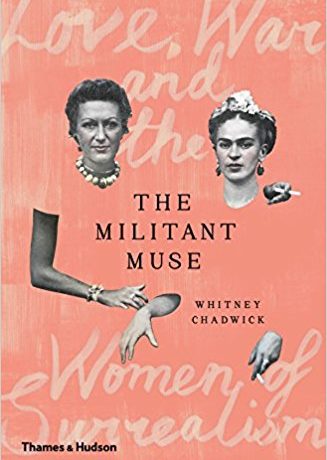

Frida Kahlo and Jacqueline Lamba, Patzquaro, Mexico, 1930

Whitney Chadwick uncovers the labyrinth of complex alliances, intense friendships and romantic entanglements that bound the surrealist community in The Militant Muse: Love, War and the Women of Surrealism. She exposes the significant struggles of its female members, who were often constrained by marriage, love or a ferocious creative connection that operated at the expense of their own artistic endeavours. Through five chapters, each functioning as something of a capsule account for a particular companionship, with distinct overlaps in several instances, Chadwick identifies the incredible connections many of these women had; albeit across continents, several decades and often through unorthodox and blurred same-sex and heterosexual couplings.

“They weren’t artists […] Of course the women were important […] but it was because they were our muses.”

As one might expect, most of these women’s stories begin as the wife or lover of the well-known male protagonists, fulfilling the duty of youthful beauty or “femme-enfant” that embodied much of the surrealist movement’s conceptual base. Leonora Carrington was still a teenager when she met Max Ernst (who was already married to an underage convent student), as was Jaqueline Lamba, wife of André Breton, surrealism’s founding father.

None of this is news, but Chadwick’s revelations surrounding the more maternal and co-dependent partnerships forged among these women (illustrated by extensively researched reams of correspondence) are remarkable. Valentine Penrose, a poet, collagist and the first wife of surrealist patron and artist Roland Penrose, comes across as something of a steadfast protector of some of her more vulnerable companions, such as the aspiring painter Marie-Berthe Aurenche, who married Max Ernst while underage before being swiftly cast aside and replaced with Carrington.

Carrington’s own horrendous hardships throughout the Second World War are also recounted in her incessant letters filled with sinister poetry, sent to Leonor Fini. The Argentine painter was another former lover of Ernst and served as a sympathetic voice as Carrington slowly descended into madness in rural France, while Ernst was incarcerated as an enemy alien. This account is the first of several to draw connections from beyond surrealism’s tight Parisian base (Fini never officially joined the group) and precedes the story of Frida Kahlo and Jacqueline Lamba Breton’s brief yet intense union in Mexico. This friendship is presented against the backdrop of the political meetings of Leon Trotsky, André Breton and Diego Rivera, and at times Chadwick’s diligent attitude towards explaining the intricacies of the trio’s discussions and affairs seem a little superfluous.

“I [would] rather sit on the floor in the market of Toluca and sell tortillas than to have anything to do with those ‘artistic’ bitches of Paris.”

The in-fighting and dramatic interludes of the surrealist men are, in my mind, still omnipresent, and at times seem stifling considering the book’s premise. But there is a fantastic irony to be found in the fact that these female-centric narratives cannot be told without this masculine framework. That being said, The Militant Muse is undoubtedly at its best when its heroines are either completely removed from male influence or are actively riling against it. Kahlo’s condemnation of Breton (she despised his efforts to exoticize her and her work) and distaste for the entire group is brilliant in its brutality: “I [would] rather sit on the floor in the market of Toluca and sell tortillas than to have anything to do with those ‘artistic’ bitches of Paris.” Similarly, Claude Cahun and Suzanne Malherbe’s defiance even when facing the death penalty for distributing resistance propaganda on the occupied island of Jersey shows just how resilient these artists remained in the face of adversity.

The first-hand accounts, archive photographs and reproductions of a beautiful selection of work throughout this text certainly build a full and luscious picture of life within and adjacent to the surrealist circle. It proves just how intrinsic these women were, whether their names remain recognizable today or not. The Militant Muse does an excellent job at conveying the opposing challenges they all faced, nearly all including stifling marriages, enforced domesticity and a near-constant struggle for their work to be taken seriously. The most potent example is found in the accounts of Lee Miller, second wife of Roland Penrose, who is more often than not recognized as Man Ray’s muse, despite her exceptional contributions as a photojournalist during the Blitz and on the front lines of conflict. She never really recovered from the trauma, and threw herself into a life of hosting, entertaining and debilitating alcoholism, while living in a tentative menage à trois with Roland and his former wife Valentine.

In Chadwick’s preface, she recalls meeting the collector at his home in the 1980s, after both of his lovers had died. On discussing the premise of this book, he was shockingly dismissive. “They weren’t artists […] Of course the women were important […] but it was because they were our muses.” It seems that even with the benefit of hindsight Penrose couldn’t recognize the incredible talents of these women and was adamant that their autonomous achievements should remain obscured, and that is, of course, why books like this are so vital.