Susan Cianciolo puts love into everything she creates. Long recognized for her clothing line, Run, Cianciolo’s boundless creativity is evident throughout her multifaceted practice, which includes designing books, theatre costumes, films and forms of ephemera that defy the categorizations of fashion, craft and art. Appreciation for Cianciolo’s tender sensibilities has been celebrated with recent exhibitions at Bridget Donahue Gallery in New York, Overduin & Co. in Los Angeles and and Stuart Shave Modern Art in London. Her work ushers our understanding of clothing away from the flighty world of trends and towards an awareness of spirituality and imagination.

I wanted to ask you about the religious aspects of your work. I know you had a very Christian upbringing. I read that your mother was Episcopalian and your father was Pentecostal.

I actually decided at four years old to join a Pentecostal church on my own. I had this calling. I would walk there and join this other family. We would travel in a station wagon, they had all of these kids and lived in a church home. So I would spend all my time there. We would go help Cambodian families and read the bible all day.

Did you ever want to be a minister?

I knew that wasn’t my calling. I felt guilty that I wanted to be an artist. I didn’t know how that was going to be helpful for the world. I saw everything that this family was doing, and my mom was working so hard as a prison guard, all her friends were nuns. We had a friend who was a lay reader and ran a soup kitchen, so we would work there a lot. I always had this feeling of, “What’s my purpose?” All the people around me were humanitarians and kind of saintly. Obviously, that was very influential. In the church I joined they would speak in tongues. I was baptized at twelve. It was very intense.

When did Eastern practices enter your spiritual life?

I remember it was around nineteen or twenty, when I was living in New York. I moved here when I was seventeen. I just started to get books and to read about different religious practices. My mom had a friend in Providence, Rhode Island who we would visit. She had a room with a crystal ball, she would tell me to go in there and meditate. We would eat macrobiotic food and do yoga. Through yoga I was led to mediation, which now is the biggest part of my life. That whole transcendental state really lends itself to my work.

“It’s not meant to be a message, I don’t want to preach. I just follow my instincts”

But this is in a different way to in the nineties, when I would go on psychedelic trips and make such large bodies of work. You can’t sustain that. I don’t see a difference between my childhood religious practice and Eastern spirituality because to me there are no rules. There is the same feeling. That is a lot of what I’m talking about in the work. Especially in the new Run church and Run prayer room. A lot of the aspects of these works are taken from Shintoism, which I learned about while in Japan. I was able to understand the sense of God in nature. All of their gardens are a form of worship. That was a big influence for me. I’m always trying to learn and pick up different methods.

I appreciate the fact that while there is sacredness in your work, it’s not treated with a sense of fragility.

That’s on purpose. Just to show that everything is sacred but we shouldn’t take it too seriously. Material should never take over our life. It’s not meant to be a message, I don’t want to preach. I just follow my instincts.

Where do you source your fabrics?

Well [gesturing to materials], this is one that a textile artist from the Bronx gave me, these were all sourced in Maine where I usually go in the summer, this I did by hand, this little piece from the corner is from a textile studio I work with in New York called Thompson Street Studio; we make a home collection together. This group of materials just came back from Paris. There’s a child’s shirt in there that I got in Jamaica, these are bedsheets, this is a piece my daughter made… Friends from Japan send me things that they weave by hand. Bridget [Donahue] gives me things. But I don’t take everything, I only take pieces I know I’m going to use. I either like something or I don’t.

So you treat the textiles that you collect?

Yes. This one has been in the sun and the rain for the last year. I usually leave them outside to see what happens with weather treatment after natural dyeing. There’s an experimentation of materials and binding: I use tapes, glues, threads. I’m interested in all the possibilities.

Which other artists working today do you feel a connection with?

I’m close to Torey Thornton, I asked him to make the money that was used for the Run store within my show at Stuart Shave Modern Art last year. When I did the original store in 2001, I had Chris Johanson make the cash. I’m not out there so much, I don’t know too many artists because my work takes up so much time.

But I get to see the shows at Bridget Donahue’s gallery and thankfully I really connect with all the artists. I’m a big fan of Jessi Reaves’s work, I have two of her pieces. I recently went to the lecture that Martine Syms gave at the MoMA and I was so completely blown away. She’s my hero, such a genius. I was so enamoured. She was so relaxed, eloquent and natural. Lynn Hershman Leeson is a hero as well, and I’m also a big fan of Monique Mouton. As a painter, I’m very drawn to her work.

There’s a strong emphasis on child’s play in your work, and you often collaborate with your daughter. Do you see this aspect of your art as a form of subversion or is it just natural to you?

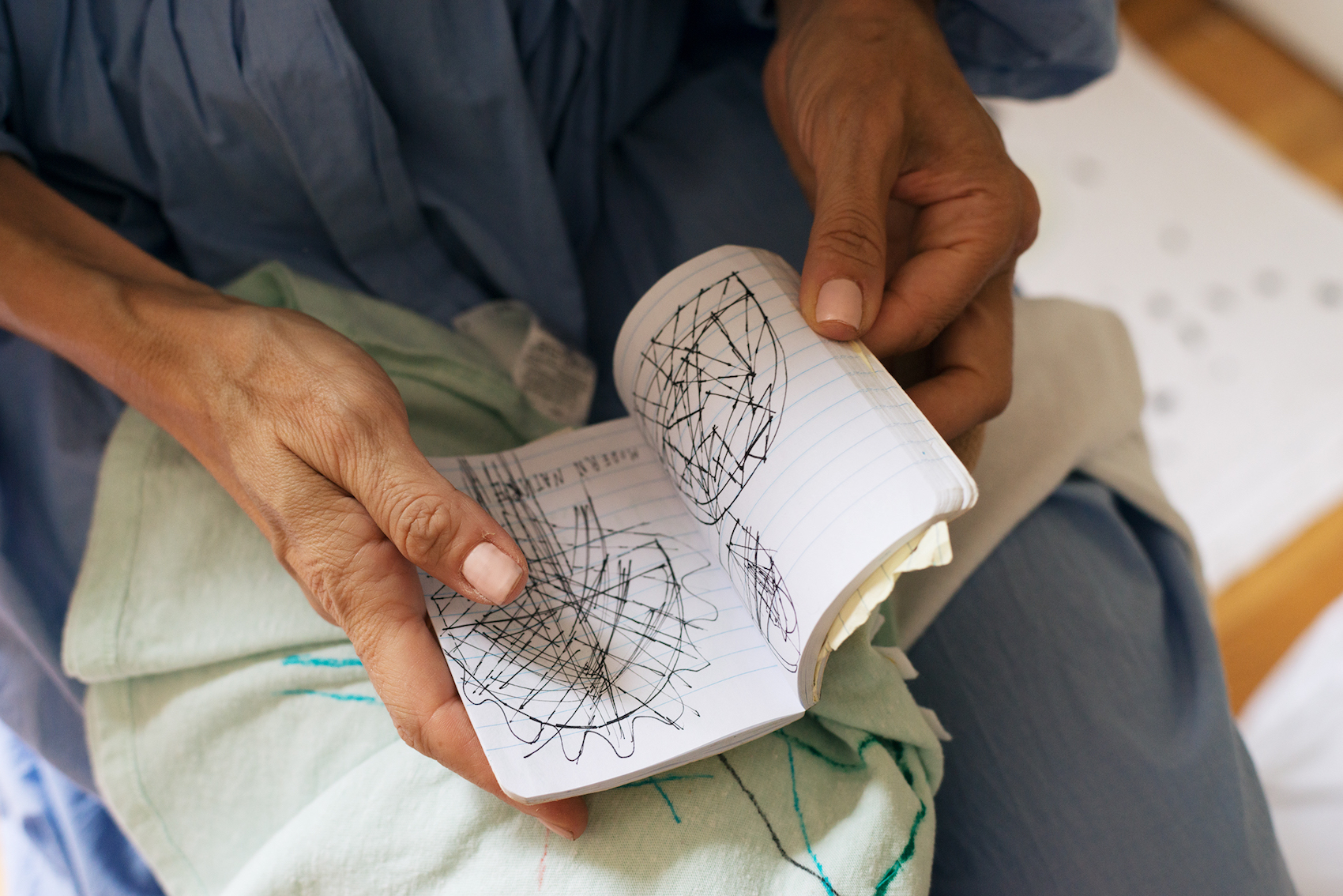

I don’t think I’ve ever done this consciously. Mark Gonzales has always been my favourite artist, I always loved his work for not being trained and his poetry for being misspelled; I wouldn’t even say the word “wrong”. He was from the school of Alleged Galleries, which was run by my former husband Aaron Rose. Everything was untrained work that became art—graffiti and so on. That was my education, so when I see what my daughter makes, it seems to me that it’s the best thing. It’s so real and pure. I’m really drawn into it. And since we’re stuck together 24/7, I see her making things constantly and it gets me really excited.

There’s such a lineage of artists deskilling themselves as a form of rebellion against bourgeois intellect, with art brut and Cobra for example. But it seems with you it’s not an artistic position.

No, it’s just a matter of me being stuck with my daughter. We argue a lot. Often she’ll tell me I can’t use a piece of her work, other times she’ll want to be involved. It just happened out of necessity. I had to continue, I didn’t have a choice. The first three years of her life she was in my studio every day. She was always filthy, disgusting, covered in dirt. The place was a mess. Things have just carried on as part of the reality of being an artist with a child.

So your work has adapted to you being a mother?

Yes. I remember when I was pregnant and she was newborn, I was making fashion collections. I felt a new energy just from having this other being around me. In everyday life I’d be making something and see this little person scribbling and just realize, “Oh wow, that is so much more beautiful.” I remember when she was very young I got this job to do a cookbook which was called This Cookbook Is Made for Jesus. I remember at one point we were on lockdown because she got lice from daycare, and I was on deadline for this book, so I just told her, “Ok we’re stuck in the house so you’re going to learn how to collage.”

I gave her a bottle of glue and she just started. For the cover I drew all the vegetables and she coloured them in. It was really just a matter of, “How do I get this work done?” In that moment I realized how much better she was than me, the way she would place things was so intuitive. As I watched her, she would really react and be emotional and go crazy. It helped me to see how much more open I could be with things, it really helped me. She taught me to be free.

Photography © David Lurvey