When I was a child, I was impressed by the number of Christmas cards my parents received. I can recall being especially struck by the large cards that reproduced, with what seemed almost indecent sumptuousness, famous paintings of festive scenes. Of course, that’s not quite how I thought of them at the time: this was my introduction to, for instance, Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Hunters in the Snow, and when I later saw the original, in Vienna, my reaction was along the lines of “Oh yeah, it’s that Christmas card design.”

Another staple was what I am now able to identify as Winter Landscape with Skaters, which hangs in the Rijksmuseum

. I probably saw it a dozen times before I checked who the artist was—and to this day the name Hendrick Avercamp is simply one of the ornaments of Christmas, scarcely less of a seasonal fixture than crackers, mince pies and sulphurous Brussels sprouts.

Many of the cards I admired as a child featured religious scenes of the kind invoked by Christmas carols: “Away in a Manger”, “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks by Night”, “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing”. But today only a small proportion of the ones displayed in our sitting room illustrate sacred subjects, and when I picture a slightly older version of my daughter Athena, curious about the reasons for the season, I can see that if our Christmas cards informed her view, she’d think it was all about robins and rib-sticking food.

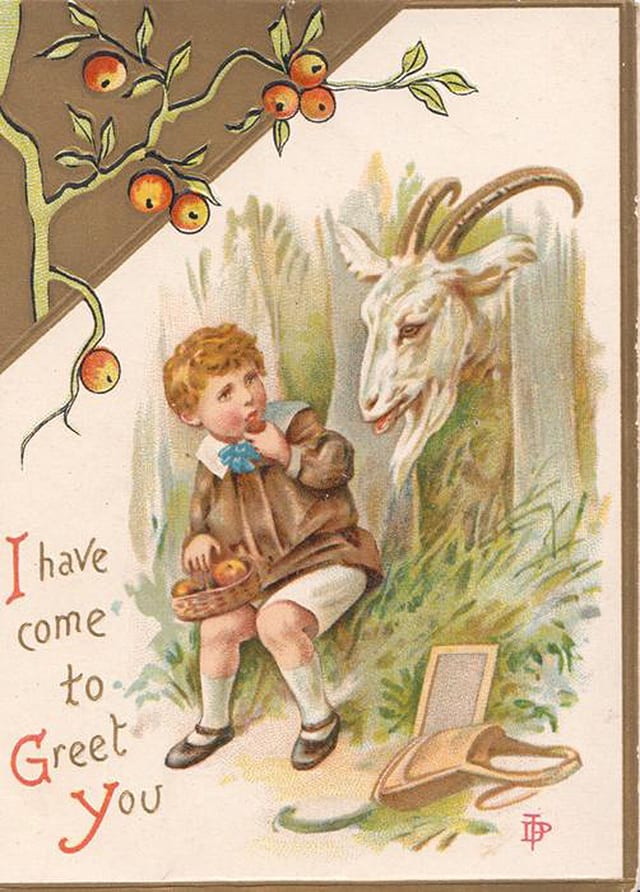

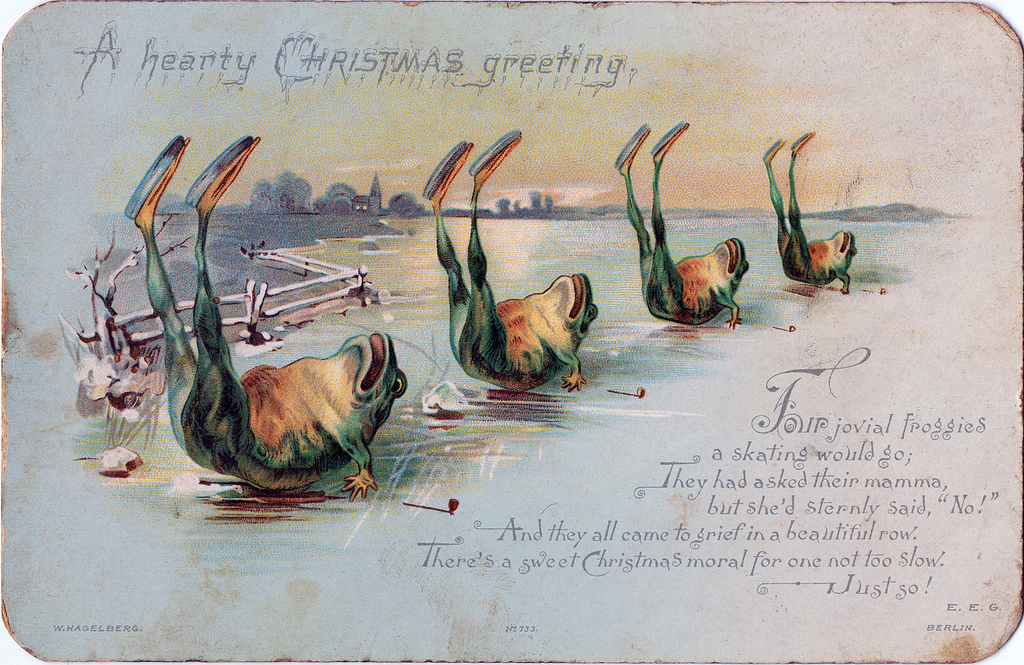

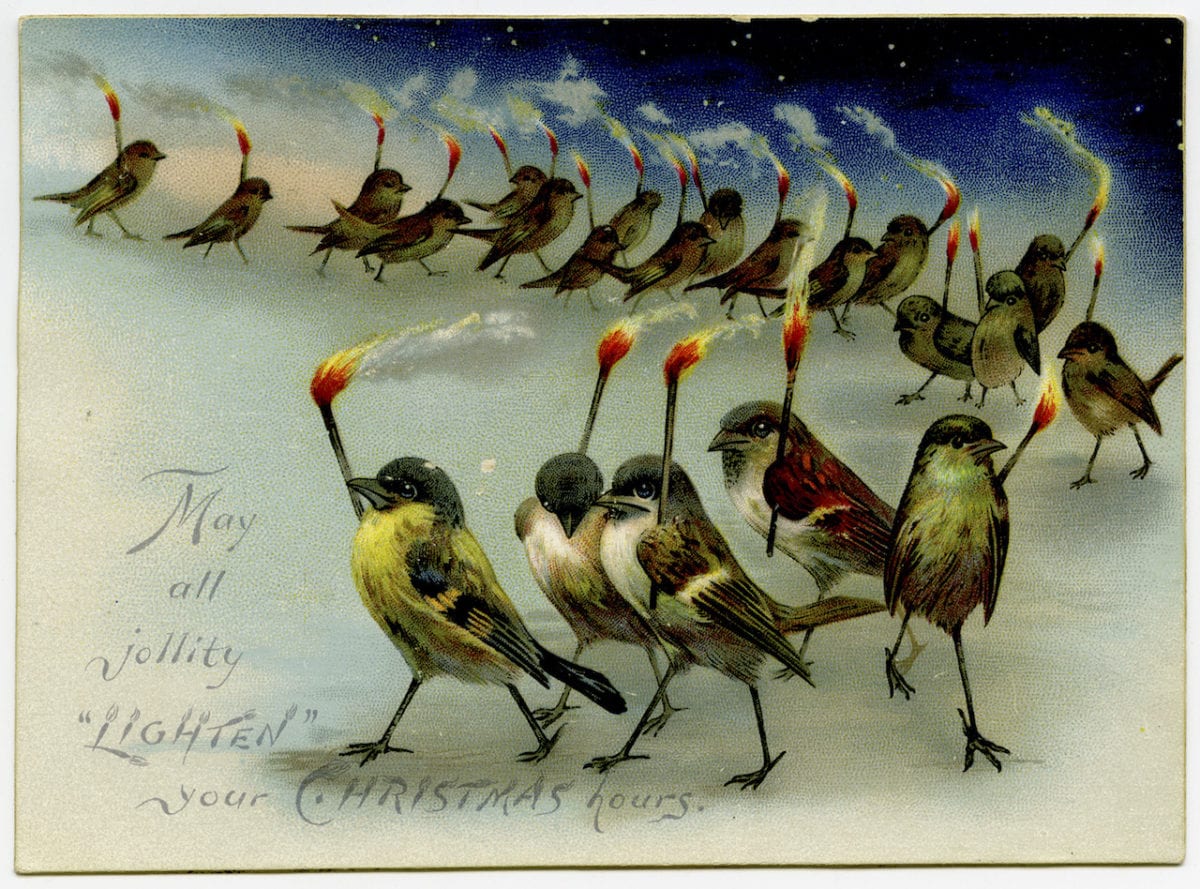

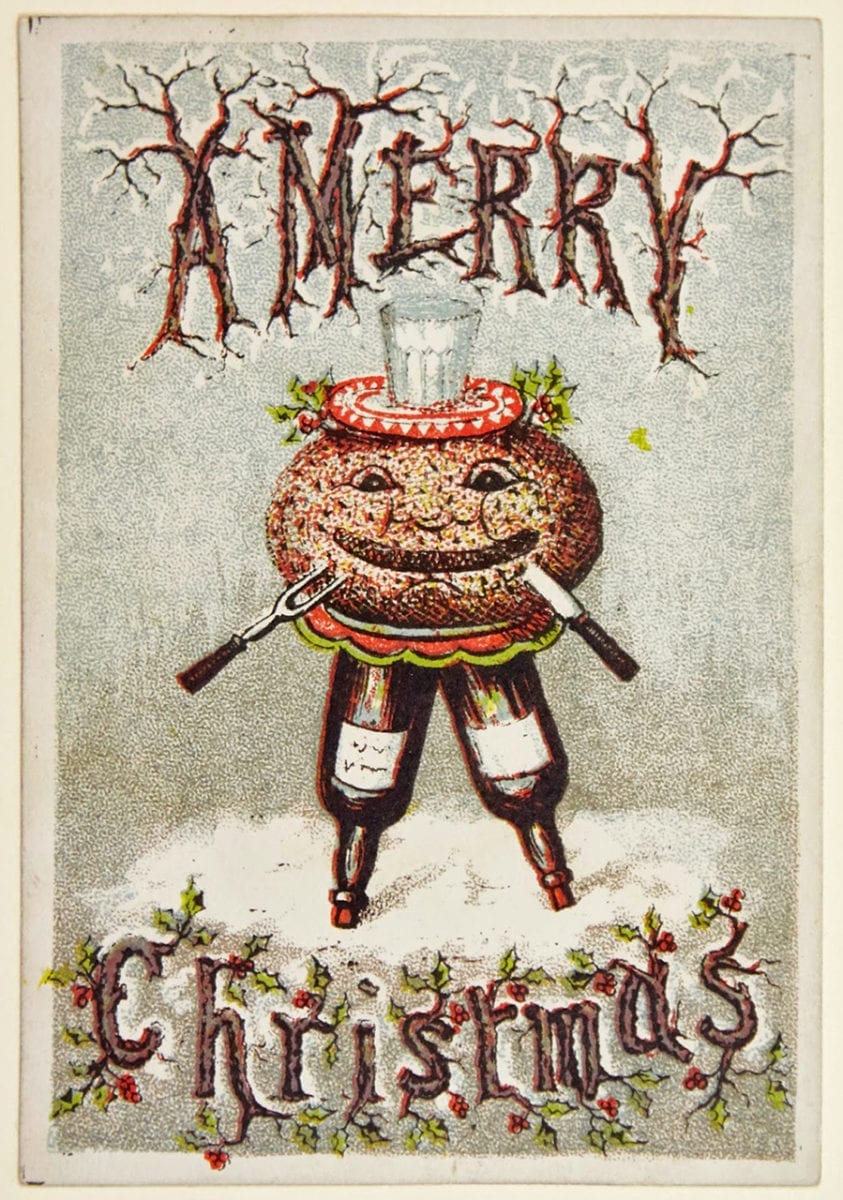

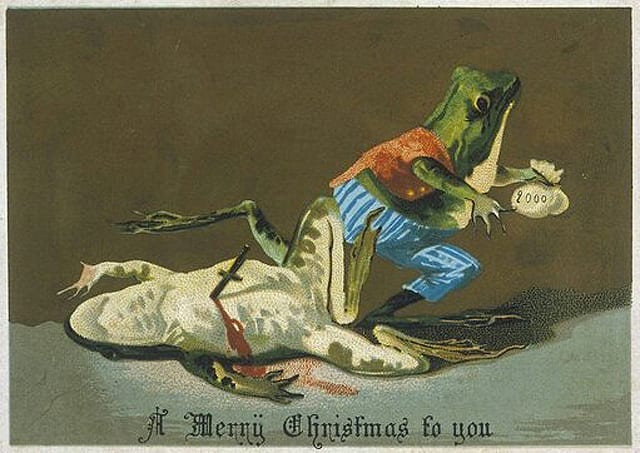

I remember learning in my teens that the sending of Christmas cards is not a very old tradition. It felt like an essential December ritual, so I was surprised to find that it originated in the 1840s, around the same time as Christmas crackers began being marketed (as cracker bon-bons or cosaques). The first Christmas cards often gave prominence to flowers, bells and snow, but some Victorian designs were positively bonkers: owls in top hats, ice-skating frogs flat on their backs, cats promenading on their hind legs with umbrellas in their front paws, a goat startling a child with the words “I have come to greet you.” Although such quirkiness is now less common, I’m able to show Athena a contemporary card of a dinosaur disguised as a tree (“Christmas Tree-Rex”) as well as one that exhibits “Cheeses of Nazareth”.

“It is worth noting that the church has long found the Adoration a ‘useful’ image, inasmuch as it suggests that, from birth, Christ was venerated by wise and regal figures”

As it happens, though, the first card we received this year, from someone I know to be an atheist, reproduced Guido Reni’s The Coronation of the Virgin. Visitors to our home might also spot a couple of cards depicting the Adoration of Christ by the three wise men. A few days ago, I found myself gratuitously explaining to eight-month-old Athena that this gift-bearing trio are more poetically known as the Magi, and that the gifts they brought were gold, frankincense and myrrh. Mentioning the last of these reminded me, as ever, of The Life of Brian: the question “What is myrrh, anyway?” and the not entirely compelling explanation that it is “a valuable balm”.

The Adoration of the Magi is a religious scene that resonates with a secular audience because it depicts the giving of presents—with all their symbolic freight as tokens of sacrifice. This isn’t the place to survey changing attitudes to such seasonal gifts (which used to be handed over not at Christmas, but at New Year), or to reflect at length on George Bernard Shaw’s claim that the commodity-glutted modern Christmas is “forced upon a reluctant and disgusted nation by the shopkeepers and the press”. Yet it is worth noting that the church has long found the Adoration a “useful” image, inasmuch as it suggests that, from birth, Christ was venerated by wise and regal figures.

There are celebrated paintings of the Magi by Botticelli, Leonardo, Dürer, Velázquez and Rubens. The story is also the subject of a tapestry composed by Edward Burne-Jones for William Morris; ten versions of it were created and can be seen in spaces as different as the Hermitage Museum and an Anglican church in Sunderland. Hieronymus Bosch made it the focus of a triptych, now in the Prado: among its more unsettling features are Herod’s soldiers gathering in order to hunt down the infant Jesus, an owl in the hayloft contemplating a dead mouse, and a monkey being conveyed on horseback towards a brothel.

My favourite example, though, is by Jan Gossaert, a Flemish artist of the early sixteenth century who is far less well-known than Bosch or Bruegel. Dating from between 1510 and 1515, it’s in many respects conventional. But Gossaert is exceptionally attentive to textures, and there’s a huge amount going on in the picture.

To revise a familiar saying: the divine is in the detail. Gossaert shows the Virgin and Child receiving their royal visitors in a ruined building; weeds sprout from between the floor slabs, and creepers snake up the walls. One of the Magi, identifiable as Caspar, has presented Christ with some coins in a gold goblet, and Christ holds one of these as if it’s a communion wafer he might bestow on his guest. At Caspar’s feet are the lid of the goblet, his hat and his sceptre, all finely delineated, but perhaps more immediately striking are the wart on his cheek and the unusual Vulcan shape of his ear.

Behind Caspar stand a couple of shepherds: one clutches a musical instrument, and the other brandishes a trowel. On the right is Melchior, holding with no apparent effort a large vessel of extraordinarily intricate design. Meanwhile Balthazar is moving in from the left, and we can see the outline of his toenails through the delicate leather of his boots. Behind the Virgin, an ox and an angel peep through a doorway. A dog, bottom right, seems taut with alertness. Higher up on the right, a man in a turban approaches on horseback with an ornamental hammer, looking furtive.

Such particularity was an advertisement of the artist’s skill. It makes looking at the work a bit like trying to solve a mystery, and it may serve as a reminder that, when obviously important events are unfolding, it’s worth paying attention to whatever is happening on the margin. It also reinforces the sense of this occasion’s momentousness: Christ is born, Christ is adored, and every nuance of the painting contributes to one’s understanding that this is an episode dense with significance.

“At their heart is something that has the power to magnetize our interest”

As a parent whose baby is experiencing Christmas for the first time, I can’t help being stirred by this image of an infant who is an object of enraptured, munificent scrutiny. Although Gossaert’s Christ occupies about one per cent of the canvas, the eye keeps returning to him. That’s as it should be—doctrinally correct. But there’s an interesting tension between the way the painting invites us to examine all its other details and the way it draws us back to the central figures of mother and child. I find myself thinking about how both Christmas and parenthood involve this double attention: at their heart is something that has the power to magnetize our interest, yet the reactions it provokes all around us can become sources of fascination in their own right.

There are differences, of course. Only members of Athena’s family are likely to regard her as the light of the world. On a more trivial note, her presents will be wrapped, and you can be pretty sure that the wrapping paper will afford her more pleasure than the contents—which prompts the unkind thought that we could just give her wrapping paper enveloped in more wrapping paper. No one’s going to be bringing frankincense for her. And gold? She should be so lucky. As for myrrh, the closest she’ll be getting to a valuable balm is calendula face cream. I’m also reasonably confident that I won’t be seeing any of our guests’ toenails—though I’m bound to see hers, when the excitement of being adored causes her to wriggle out of her Rudolf the Reindeer slippers.