This year marks two decades since the pilot episode of Sex and the City. When Carrie Bradshaw first broke the fourth wall, Samantha Jones introduced us to the rules of the free-market-feminism that bound the show, Miranda Hobbes wore a bucket hat over a hoodie, and Charlotte York went back to Capote Duncan’s to “see the Ross Bleckner”. Not for the first time, or the last, contemporary art was brought in on the action (or as part of a ploy to get some).

A year earlier, in Los Angeles, Amanda Woodward, the head of advertising agency D&D, had brought her love interest, Kyle McBride, to an art opening at the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (MOCA), in episode 28 of the fifth season of Melrose Place—a spin-off of Beverley Hills, 90210, which followed a group of twenty- and thirty-somethings living in the same apartment complex. Much of their date took place in front of a Bleckner-like painting—as described by William Grimes in The New York Times—which alluded to the American bombing of Baghdad.

The GALA Committee 1995-1997 Exhibition, Red Bull Studios New York, 09-28-2016

Amanda: You know, I wanted to major in art.

Kyle: (Sighing) Aaah!

Amanda: But it wasn’t practical. So I majored in business and minored in art. I went through this bohemian stage, where I considered forgetting about money, and I just wanted to travel and paint. That was my dream.

Kyle: What changed?

Amanda: Poverty sucks!

Kristin Davis, who played Charlotte York in SATC, had previously been entangled with Amanda in a web of blackmail and drama in season 4 of Melrose Place, as Brooke Armstrong, an intern at the ad agency. She missed the MOCA show having drowned in a courtyard pool in episode 20, after a boozy argument with her ex-husband (and Amanda’s ex-lover); she also missed the grand unveiling of the PIMs (Product Insertion Manifestations), orchestrated for Melrose Place by the GALA Committee.

Conceptual artist, and GALA Committee founder, Mel Chin had stumbled upon Melrose Place when his wife, flipping channels, landed on a scene with Heather Locklear, who played Amanda Woodward, speaking in front of a painting. It was the mid-90s and he’d recently been approached by the curators of the MOCA exhibition Uncommon Sense, a show that would comprise the newly commissioned work of six artists who were interested in both social issues and engaging people who wouldn’t normally frequent galleries. The clip from Melrose Place, plus his interest in working out how artists might work with TV—a theme Chin was exploring in his teaching at the University of Georgia and the California Institute of the Arts—led him to the conclusion, “That’s the gallery”.

“They called the project In the Name of the Place, and recognized it as a viral, conceptual public artwork to be conducted on primetime TV.”

Although the cast of Melrose was older than that of 90210, they swung between love and hate like teenagers, and created countless opportunities for new layers of meaning to surround their absurd interactions. The show’s production team went for it and, for the next two years and two seasons of Melrose Place, the Gala Committee embedded PIMs in the storylines, homes and workplaces that made up the show.

In its artist’s statement, the GALA Committee wrote: “[We] sought to work with commercial television by actively approaching it as a proper site in which to develop possibilities for education, to generate the transfer of information, and to layer narratives and poetic construction.” They called the project In the Name of the Place, and recognized it as a viral, conceptual public artwork to be conducted on primetime TV.

The GALA Committee’s interventions included bedsheets with a repeat pattern of unrolled condoms on the bed of womanizing Dr Peter Burns, and a quilt appliquéd with the chemical symbol for the then-illegal abortion pill RU-486 that covered the accidentally pregnant Alison Parker (when unwanted pregnancies on the show had previously been dealt with by a dramatic fall-down-the-stairs, rather than any storylines involving reproductive rights).

Hockney-esque paintings (supposedly painted by Samantha Reilly, the show’s resident artist) depicted the infamous locations of LA deaths including Sharon Tate’s house, Marilyn Monroe

’s bungalow and the Ambassador Hotel where Robert F Kennedy was assassinated, and Chinese takeaway boxes that read “human rights” or “turmoil and chaos”, referenced the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989.

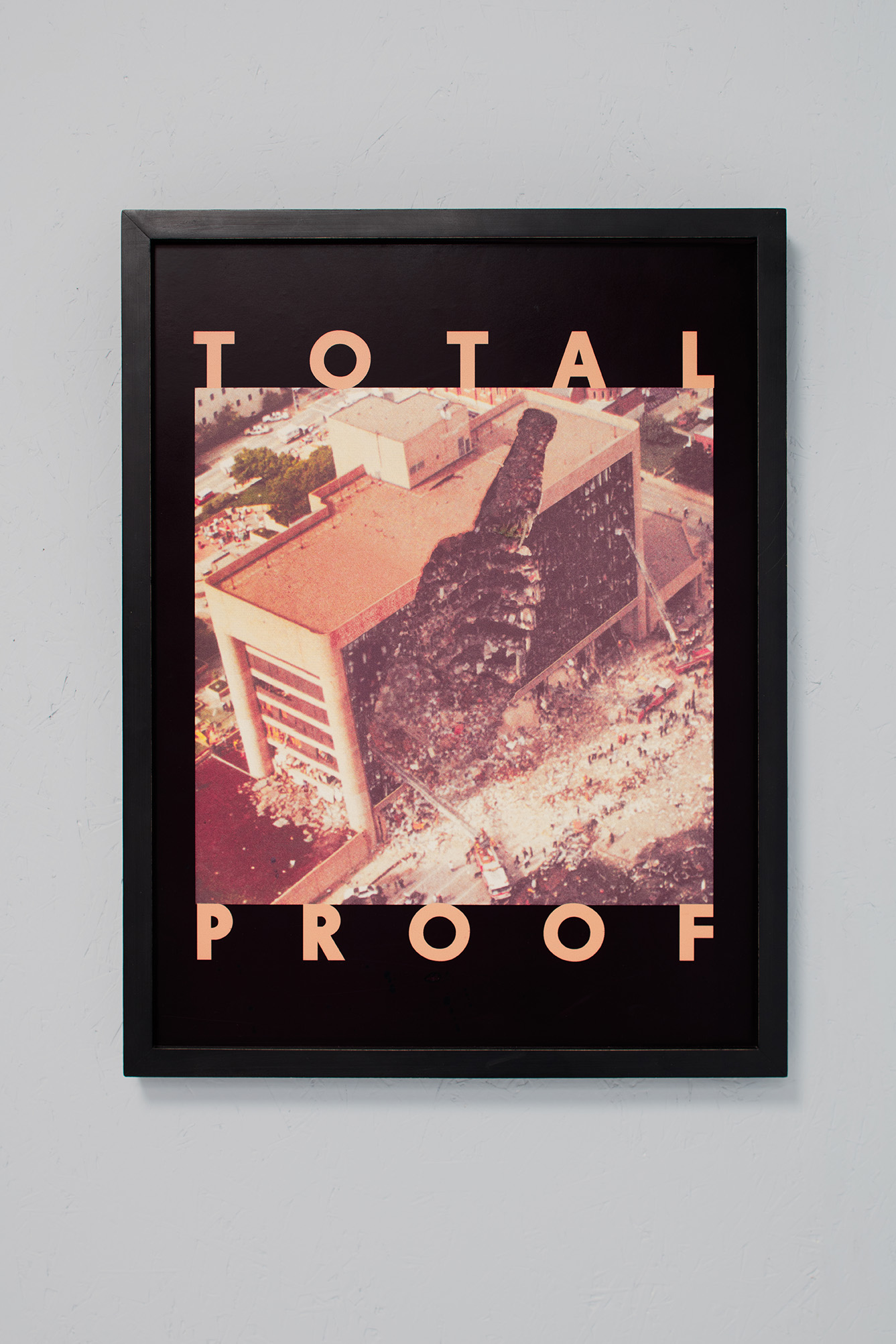

The PIM that created the biggest stir, and finally provoked the attention of Aaron Spelling and the cast, was a vodka ad campaign called Total Proof, which depicted the wreckage of the 1995 Oklahoma Bombing (and took its title from an altered photograph of the site), with the shadow of a vodka bottle embedded in the building. The piece had been ruled too offensive, but somehow ended up on the wall of D&D Advertising, behind Allison and Amanda in their last showdown at the company—which also nearly became the GALA Committee’s last hurrah.

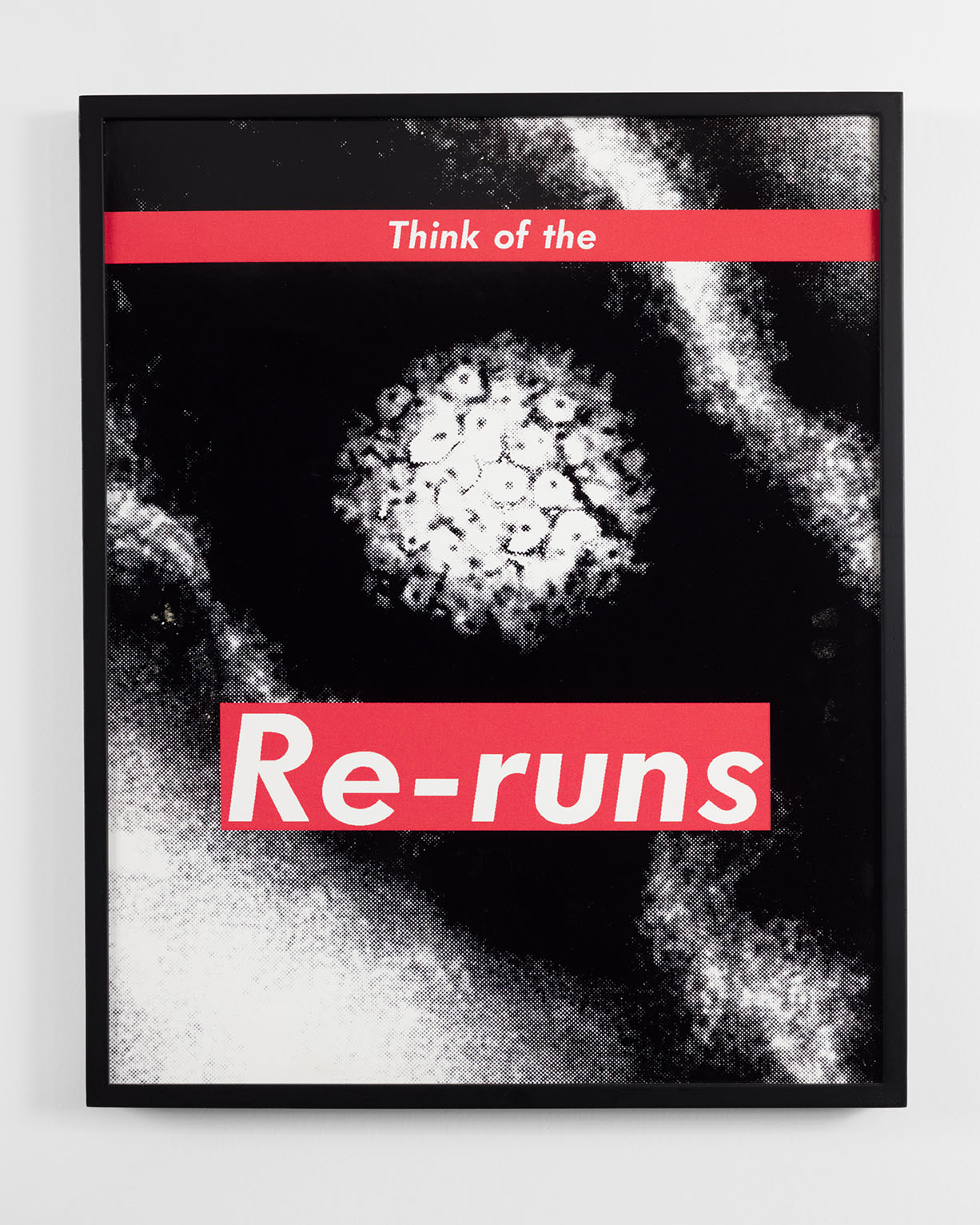

Back at MOCA, Amanda and Kyle’s in-situ date coincided with a piece in The New Yorker, titled “Agitprop”, which coincided with the real-life opening of Uncommon Sense. In the piece, Mel Chin was interviewed about In the Name of the Place, the thematic links between the props and the show’s treacherous characters, and how he’d been inspired by Goya’s Los Caprichos—the salacious etchings of the Madrid aristocracy that he subsequently sold back to them. Chin imagined an ecology for In the Name of the Place that would rely less on the project’s time in the gallery, and more on the space of TV, where ideas could re-run until we all “got it”.

It could be understood as a form of parasitism, informed by the revelatory potential of fiction, and the power of broadcasting secondary messages and meanings within an endlessly repeating and comfortably recognizable structure. In his synopsis of the work on his portfolio site, Chin explains: “This project of covert insertion wasn’t intended to be subversive, but to offer a blueprint on how artists can collaborate with commercial production from the ‘inside.’”

For the GALA Committee, the belly of the beast was the centre of the action. In the Name of the Place culminated in a glamorous charity auction in Beverley Hills, where its collectively-made works of art were sold off by Sotheby’s to patrons that resembled their fictional peers.

- Pages from the catalogue of the Prime Time Contemporary Art Gala Committee Auction

Melrose Place faded out with the twentieth century. Its final episode, “Asses to Ashes”, aired in the summer of 1999. A couple of seasons earlier, the character Megan Lewis had been introduced. She was a hooker employed by the wife of Michael Mancini (long story) who was played by Kelly Rutherford. Despite her various entanglements, marriages and attempts at murder, Rutherford held out until the show’s final episode, and a few years later, reappeared as Upper East Side matriarch Lily van der Woodsen, in the teen drama Gossip Girl.

“The painting took on a character as central as Bass, or any of his vapid frenemies”

Developed by Josh Schwartz, who had previously created The OC (a show indebted to the 90210/Melrose Place family), Gossip Girl also adopted the principle of the TV drama as gallery. Working with the Art Production Fund—a non-profit producing public art projects—the Gossip Girl team had the work of contemporary artists installed throughout the show. The main location was Lily van der Woodsen’s apartment, from which party guests could enjoy works by Kiki Smith, Richard Phillips, Marilyn Minter and Elmgreen & Dragset (whose Prada Marfa sign was specially commissioned for the show).

But rather than being a project of “parasitism”—as Chin had described, In the Name of the Place—on Gossip Girl, the art wasn’t adding layers of meaning, it was rather, inserting itself into the centre of abundantly meaningless escapades. In perhaps the next logical step of Chin’s intention to show how artists could collaborate with commercial production from the “inside”, artists and the APF appeared on the show as characters, the work itself often took on central roles, and could later be bought as prints.

When Richard Phillips’s Spectrum got embroiled in Chuck Bass’s scheme to have his back-from-the-dead father imprisoned on the grounds of an illegal oil deal with a Sudanese sheikh, the painting took on a character as central as Bass, or any of his vapid frenemies. In both Melrose Place and Gossip Girl, the revelatory power of fiction was explored. For the former, it was in the Gala Committee’s PIMs, adding meaning while hiding in plain sight; in the case of the latter, it was in the way the artworks were co-opted into the teen drama, caught up in the fizz, and giving up meaning for the sake of becoming a piece of the action.