Though the artists are fine with visitors missing their work–it’s also the case that even if you don’t want to see their work, you’ll come across it anyway at their new exhibition, since it’s dotted all around the place, without any labels, like a treasure hunt (there’s a map available for the intentional visitor).

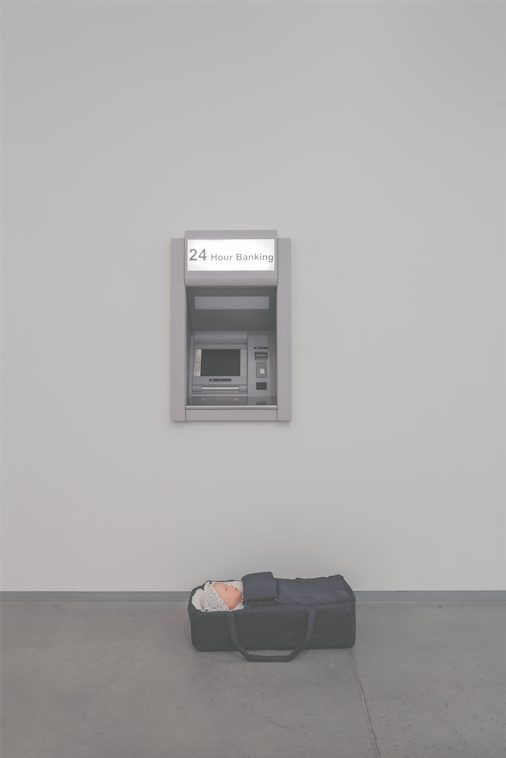

Some of their sculptural works, such as Modern Moses, (2006)–a very realistic cash machine with a too realistic baby in a cot underneath–had already received complaints from concerned visitors. Among the European masters of the 16th – 19th century hangs their sardonic send-up of the selfie, Portraits of the Artists, (2014) that nods to their solo exhibition at Victoria Miro last year. Other works are harder to miss; such as their monumental For as Long as It Lasts (2016) a life-size recreation of a section of the Berlin wall, installed in the museum’s largest gallery.

The Scandinavian duo were in attendance, leading a walking tour around their typically unconventional exhibition–their first in Israel. We put our five questions to them.

What are your impressions of Tel Aviv?

Tel Aviv as a city seems a bit brusque on the surface, like Berlin, but once you break through it’s very engaging. We found the people to be friendly and warm.

You’ve installed an exact replica of a section of the Berlin Wall at the Tel Aviv museum as part of this exhibition. Why is that?

We moved to Berlin in the mid-1990s as a direct result of the fall of the Berlin Wall. The city was open and free, offering room to experiment for young artists like ourselves back then. Berlin as a city has played a big role in our personal and artistic development. In addition to referencing our history together, the For as Long as it Lasts installation recently took on a renewed relevance, as we’re seeing new fences and walls emerge in some places in Europe, and certain candidates in the U.S. presidential election primaries are calling for a wall between the U.S. and Mexico.

You mentioned that your Powerless Structures came out of your misreading of Foucault, and his writing on overcoming systems. There was another kind of productive misreading, at the MoMA that resulted in your piece, Other Landscapes… Would you mind telling the story of how that work came about?

Of course: we were in New York and went to see the Isa Genzken show at MoMA, and there was a partly installed sign on the wall announcing an upcoming Gaugin exhibition. Scattered around the sign were all the installation equipment and ladders, and we thought this was such a great entrance into the Genzken show. It turned out that these materials were actually being used in preparation for an upcoming Gaugin show at the museum. We liked the visual impression and it stayed with us, and we decided to use the name ‘Matisse’ for Tel Aviv—referencing the lack of works by Matisse in the museum’s collection.

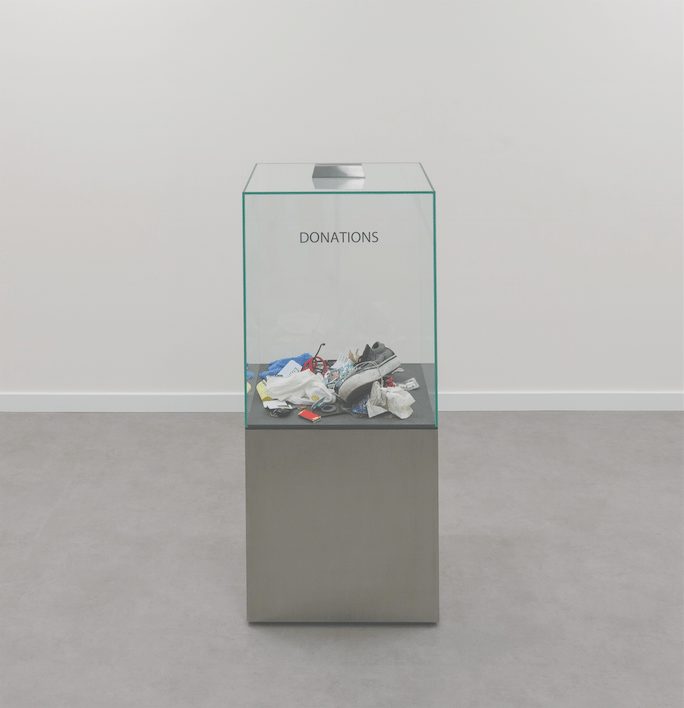

You also have had a nice chance encounter regarding your Wishing Well/Powerless Structures Fig 166 work…

Our piece Wishing Well/Powerless Structures, Fig. 166 is a round pool dug into the ground, containing coins without any imprints or denominations, and sealed with a transparent top. We made a similar work, in a square version, called Wishing Well/Powerless Structures, Fig. 66, for the first Berlin Biennial in 1998. It was installed in Oranienburgerstrasse, and we overheard a conversation between two homeless people standing in front of it: they said it was actually a very democratic work with regards to money—it remains the same whether you have money or not.

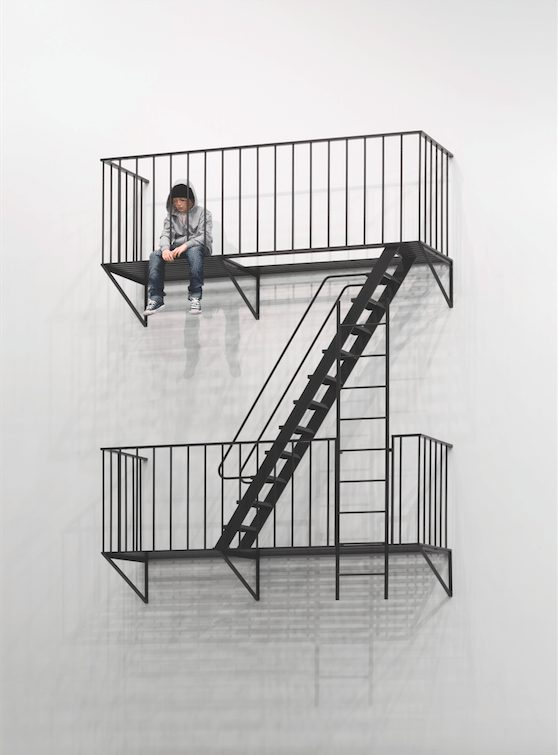

You mentioned that often when adolescents appear in your work they’re not very happy. Were you moody teenagers yourself? If these figures are our future, do you feel quite bleak about it?

Growing up is a difficult process—it was for us and on some level, it is for everyone. Rather than signifying solely a bleak outlook about the future, this work shows an introspective, quiet moment of reflection. It’s about the complexity of the future; we can’t predict what’s in store for younger generations.

‘Powerless Structures’ runs until August 27 at Tel Aviv Museum, Israel