Encounters between strangers take place every day, and yet how many of these are remembered or recorded? Russian Ghanaian photographer Liz Johnson Artur has been spontaneously documenting the people who she meets in her day-to-day life for more than 30 years, forming a deeply personal chronicle of lives from the African diaspora across Europe, America, Africa and the Caribbean.

By capturing them on film (Artur has resisted the shift to digital, consistently shooting only on analogue cameras), she holds on to these fleeting conversations with both familiar and unfamiliar faces, like the imprint of a shadow that otherwise would have passed by. “What I do is people,” Artur has said of her work. “But it’s those people who are my neighbours. And it’s those people who I don’t see represented anywhere.”

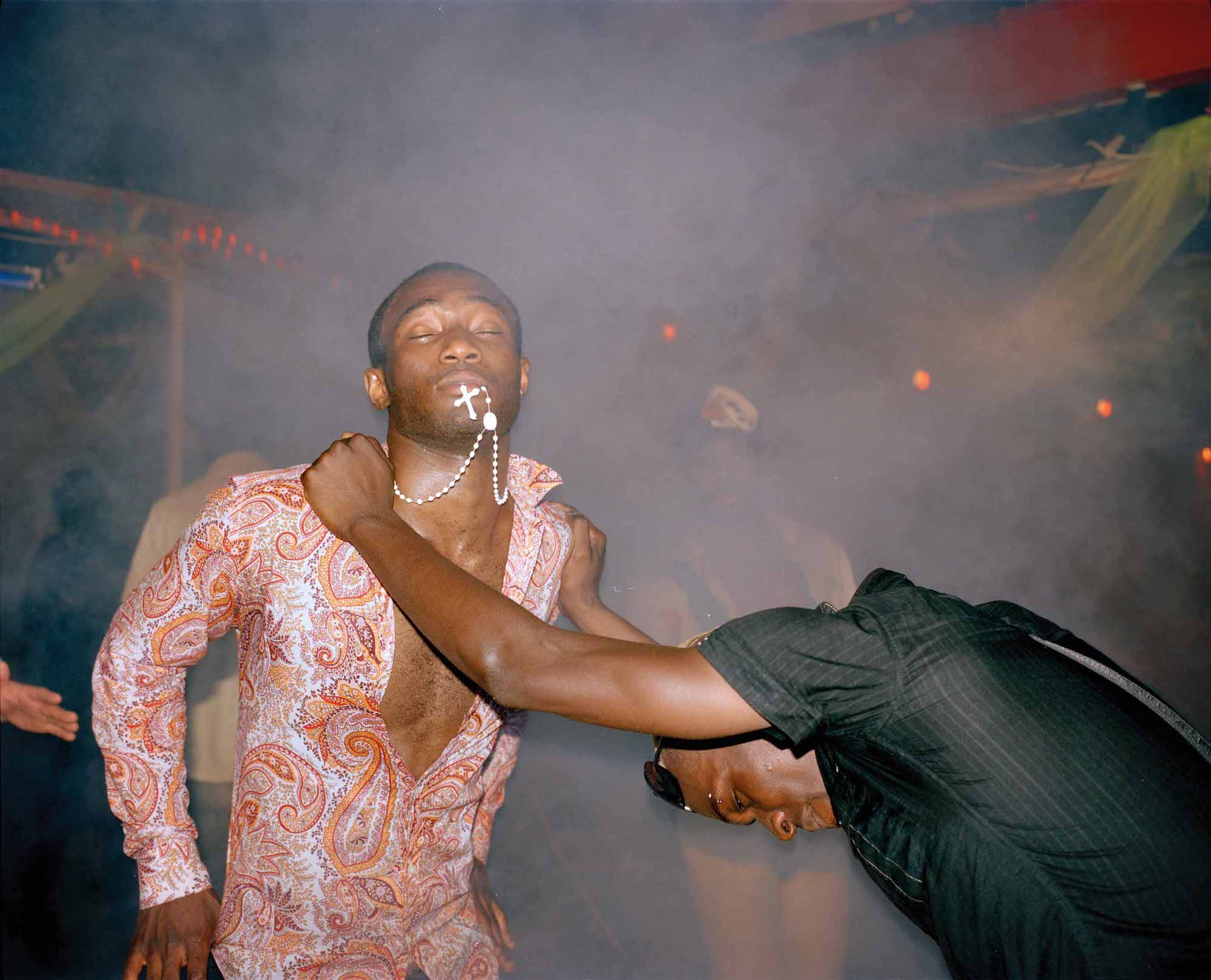

“Artur’s shot of two young men lost in blissful euphoria on the dancefloor could have been taken at any time in the past 30 years”

Based in London, the UK capital forms the backdrop to many of Artur’s shots, from queer club nights held in crowded basement bars to busy shopping streets. Her working practice often involves approaching people from beyond her own circle of friends and family, pushing herself through shyness to cross the road or bar and request permission to snap that scene and keep it for posterity.

Together these images form an ongoing archive that Artur has named the Black Balloon Archive. Each picture is unnamed and undated, with any defining descriptions stripped away. It is Artur’s intention to leave the photograph to speak for itself, removing what she sees as the limits of perception enforced by the rigidity of a timestamp or title.

Instead they expand to infinite possibilities. Artur’s shot of two young men lost in a moment of blissful euphoria on the dancefloor could have been taken at any time in the past 30 years. One of the pair faces the camera straight-on, eyes closed in abandon and shirt unbuttoned almost to the navel. A white cross hung on a set of rosary beads dangles from his mouth, catching the light of Artur’s flash as if struck by a beam sent straight from heaven.

“She holds on to these fleeting conversations like the imprint of a shadow that otherwise would have passed by”

The central focal point of this Christian cross introduces the hazy influence of religion into the frame. From the pulsing beat of the dancefloor to the rousing voice of the pastor, it is not difficult to see the connection between the two. Both lend themselves to the experience of losing oneself to a force that goes beyond conscious thought, to the power of collective emotion. There are moments of euphoria to be found in everyday life, and it is these small reprieves that animate much of Artur’s work.

Who appears in front of the camera, and who takes the pictures? A photographic archive is a powerful filter of both history and memory. Artur’s camera becomes a tool for reshaping not just her own past and present, but the future of how these people and communities will be remembered. In these photographs, the casual glance of a stranger takes on new meaning as it moves beyond the transient and transforms into something more permanent, something akin even to the spiritual.

Louise Benson is Elephant’s deputy editor

Liz Johnson Artur, of life of love of sex of movement of hope

Foam, Amsterdam, until 9 February 2022

VISIT WEBSITE