Paul Salveson, Courtesy Regen Projects

In anticipation of her upcoming solo exhibition at Regen Projects in Los Angeles, Smith spent some time via Zoom speaking to Karla Méndez about her show, what informs her work, and her intentional use of various mediums.

The layered mediums in the work of interdisciplinary artist, writer, and educator Sable Elyse Smith point to the corners of the carceral and justice system that are often hidden. The bright colours utilised in her Coloring Book series cover up the violence of the seemingly innocent intention of the lines below, sketching out images of judges, arrestees, and family members. These components call attention to the duplicity of the colouring books handed out to children whose parents have been incarcerated in an effort to help them understand the system of which they are members. Juxtaposed against the vibrancy of these pieces are her sculptures and videos, which display and mimic the emotional, physical, and psychological impact that incarceration has on families.

Smith’s work warrants a reaction of discomfort. A surface reading at a distance allows viewers to be pulled in by the colours and the larger-than-life depictions of ordinary objects like furniture, deceiving them into believing they have encountered some form of normality or safety. Yet, after closely engaging with any of her pieces, it becomes obvious that Smith has the desire for her work to disorient and force viewers to negotiate with systems of injustice. In anticipation of her upcoming solo exhibition at Regen Projects in Los Angeles, Smith spent some time via Zoom speaking to Karla Méndez about her show, what informs her work, and her intentional use of various mediums.

Karla Méndez: Can you tell me a little about your upcoming solo exhibition? What was the catalyst? What were some of the inspirations?

SES: This is my first real show in L.A., so I wanted to make sure that there was a space for all the different entry points and mediums that I’m thinking about because in some concentrated shows in the past, there would be one series and people would get attached to that. But I’m looking at and interested in these things from different directions, so this is a sampling of the processes and materials I use. There was a monumental sculpture I made for the most recent Whitney Biennial, which was basically furniture objects in the shape of a Ferris wheel. That piece and the ideas and site are the inspiration and springboard for the show. I became interested in thinking about both the temporary site, motifs, and caricature of this idea of a travelling carnival, fair, or amusement park, all spaces of entertainment, thrill, and chance that have temporariness. Particularly thinking through the history of the travelling carnival or fair, it’s a site that is put up and given a name. It’s deemed a space of entertainment, so anything that happens in that space is permissible. But if similar things happen outside of that space, then there’s conflict in what is morally permissible or not.

“I’m not trying to make something beautiful; the way I apply the paint is actually quite crude. I am using seduction as a camouflage to ground people.”

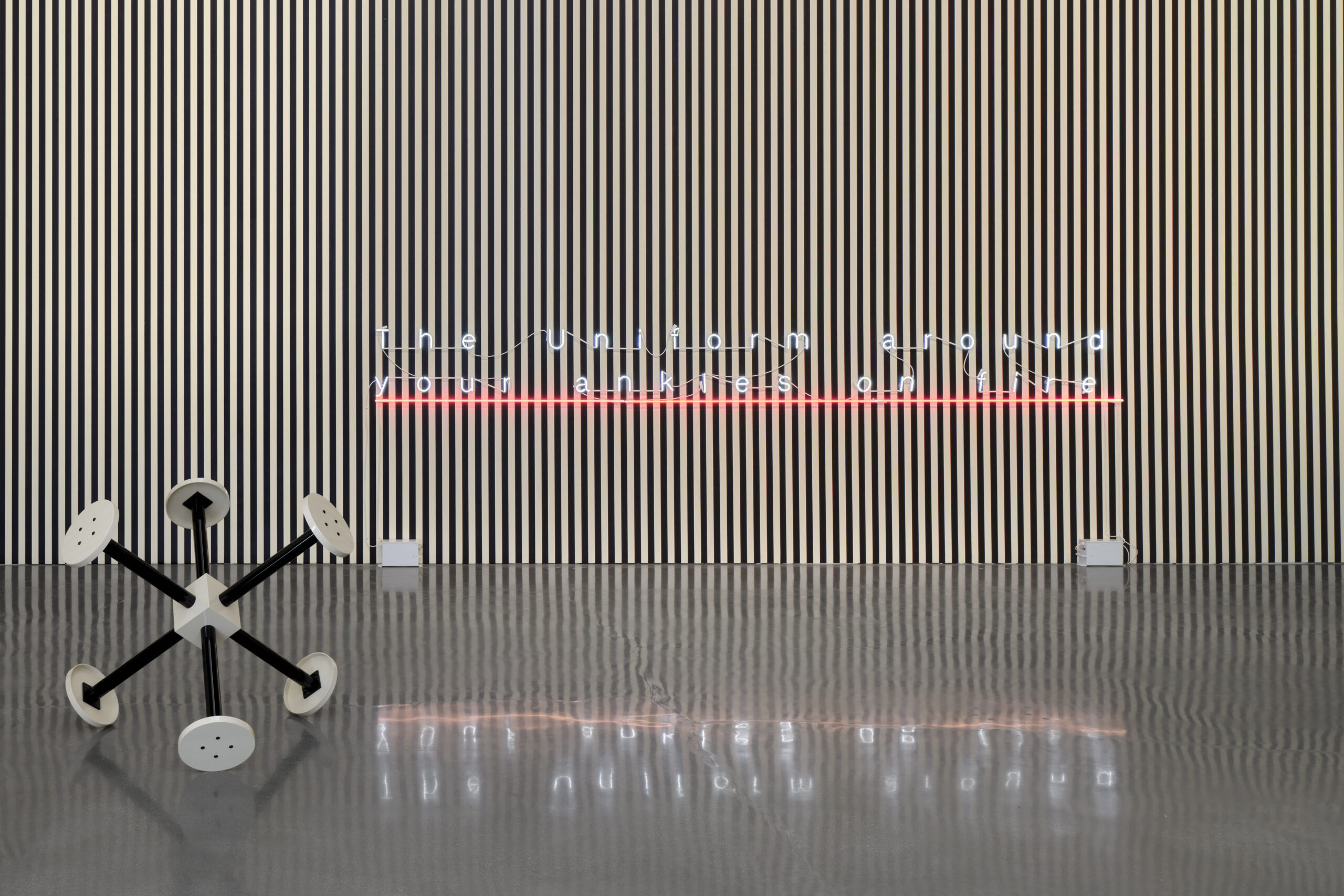

Thinking about language and naming has always been interesting, but especially pulling out an example that I thought people would be familiar with and might not necessarily question. If we’re thinking about the history of carnivals, there are people paraded around as “freak shows,” there’s violence, and people fighting each other or animals allowed in the space. The economy and commerce revolve around it, so I’m focused on using that as a caricature to reinsert this carceral context and dialogue of various systems of violence or oppression. That’s the aesthetic motif for the show.

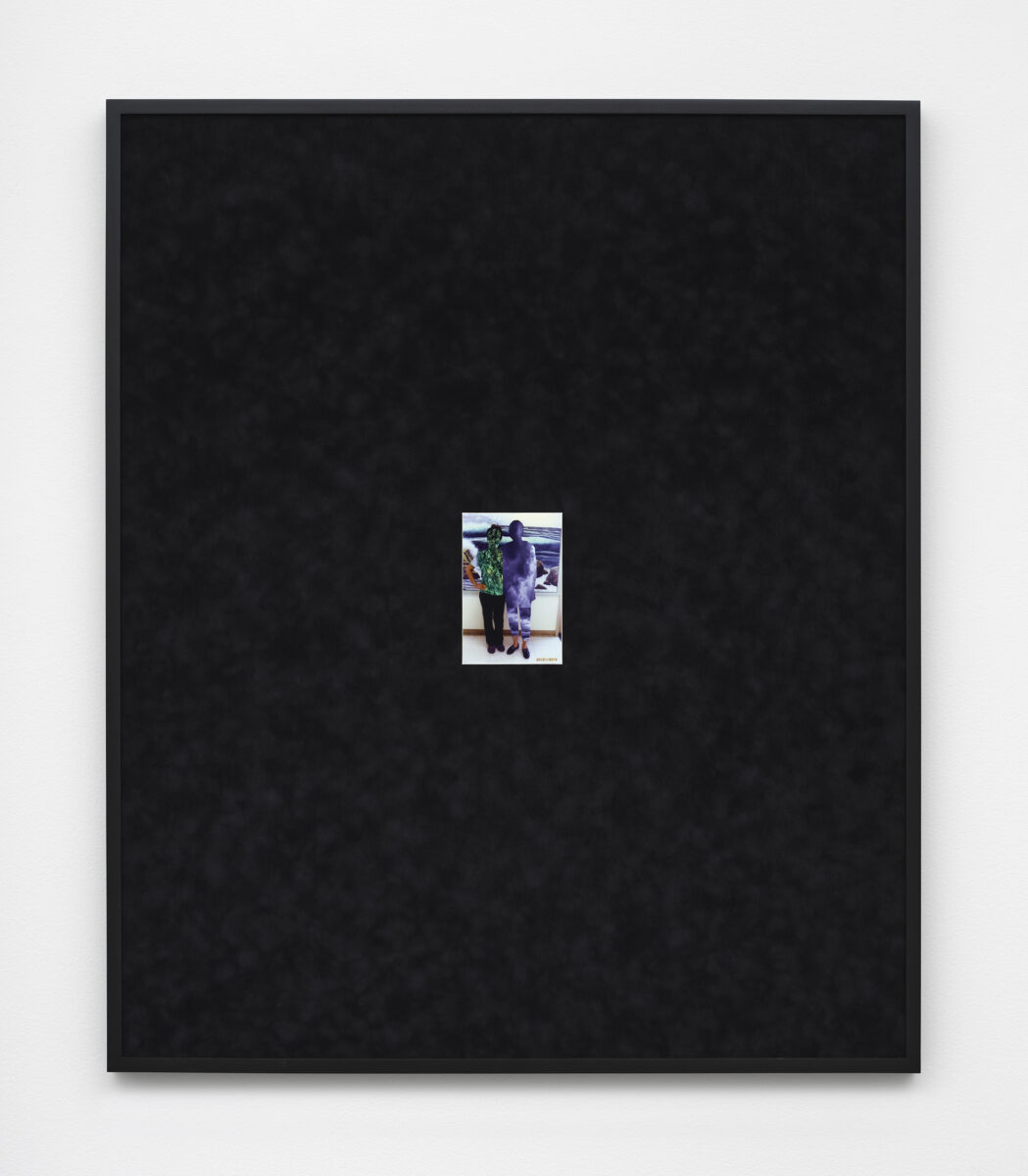

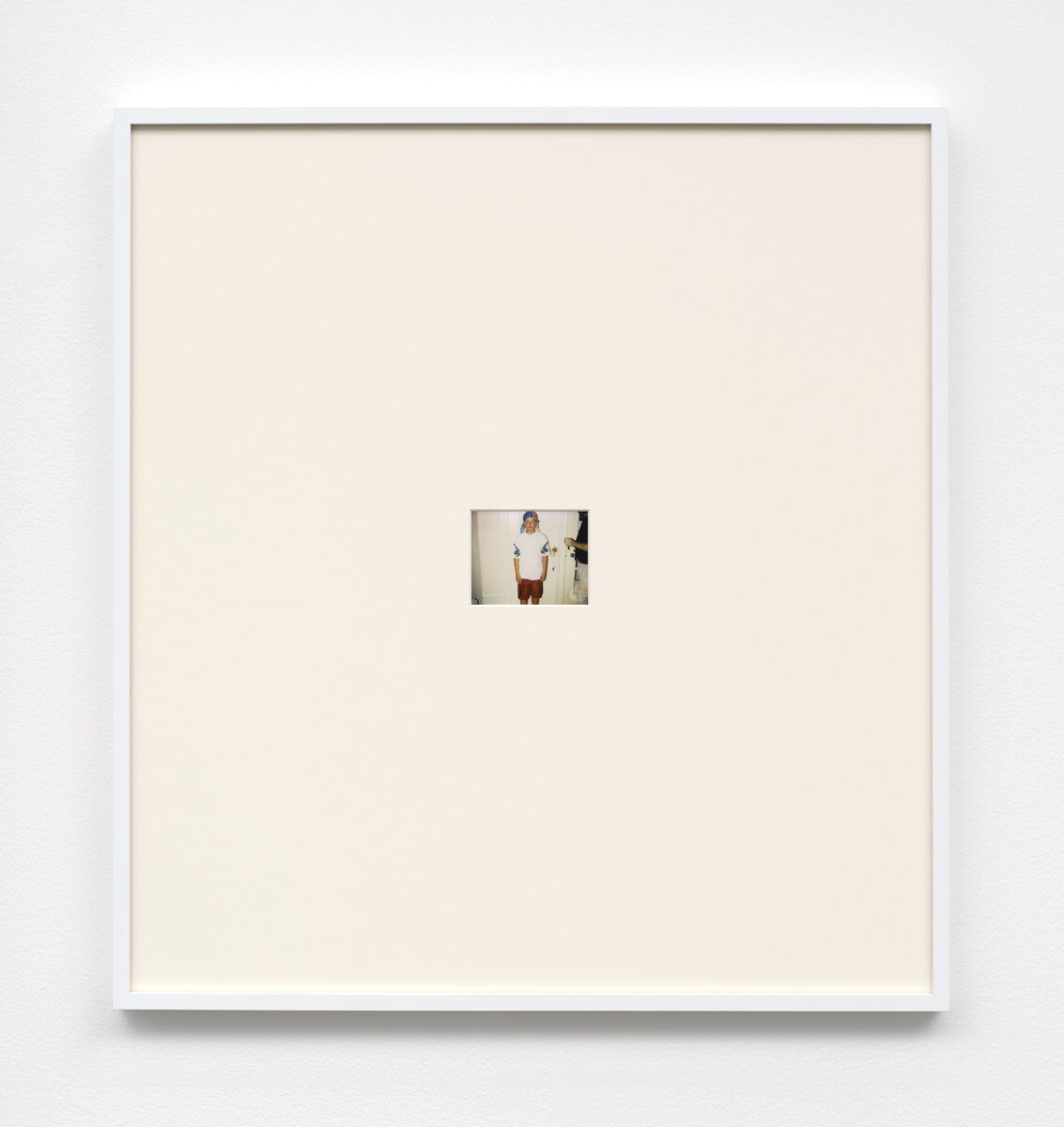

Within that, there will be two smaller sculptures from the same series, which take prison visiting room furniture and use it as a modular building block to reconfigure obsolete objects or other objects reminiscent of architecture. There are a few brand new pages from the Coloring Book series that have never been seen, with the addition of grotesque caricatures of this carnival aesthetic placed on top. There is also a new neon text piece and two different photographic series.

KM: Could you talk more about the new Coloring Book pieces and the neon pieces?

SES: The Coloring Book series is basically these multi-media works, but they’re conceptually paintings. I found this colouring book that exists and is still distributed that a child used and probably lost. I sat with it for a long time because something that stuck with me was that many people would see it as a neutral object that is well-meaning and meant to educate. I thought about the context and the audience and the way language, image, and a child’s motor skills are being asked to engage with the object. At every turn, the colouring book tells children to imagine themselves within the justice system and to constantly erase, shut down, and foreclose imaginations. In something that seems to be about education, there is a subtlety through which it creates a stricture and produces a different type of violence through projection. It asks them to place themselves in the system and in the court instead of anywhere else. I made a bunch of work from that specific colouring book and then began to research other books that were similar and created by municipalities or were state-sanctioned. I have been collecting these images and reconfiguring the ones juxtaposed together because they articulate a different narrative depending on how they’re put together.

KM: I know you’re originally from Los Angeles, but as you mentioned, this is your first real exhibition here. Is that because you’re New York-based and, as such, don’t really have a relationship with the art community here? How does it, in a way, feel to be coming home to show this new body of work?

SES: It’s weird and exciting because I haven’t lived in California for a long time, but I obviously go back and visit from time to time. And a lot about the L.A. that I know has changed and shifted. Also, when I was growing up, the art world was never a part of my life or consciousness. It wasn’t a space that I found aspirational, so I feel like it’s nice personally, but also weird to be coming back to this world and context that is mine but that as an artist in this geographical location, it is not the space, community, or context that is my muscle memory.

KM: How does your written work inform this specific exhibition?

SES: For this show, the most present impact is the titling. It’s 50/50, some people pay attention to it, and some don’t, but I do think of it as another space where it is material. It is also the medium and material of the object itself, so it’s a place to be able to play around with or provide a kind of curveball. The neon works are always text-based, so there will be a loud text in the show. I anticipate it will probably be a slow read for people because I think there’s ambiguity in it.

Writing and language were my first introduction to any kind of artmaking or creativity, so in that sense, language has always been crucial to me, and it’s the lens through which I think about physical objects and materials.

KM: You’ve mentioned in the past that in creating the colouring book pieces, you wanted to blow them up, transforming them into enormous facsimiles of the original to rid them of any intimacy or protection they could provide. Interestingly, some of your work is featured on the Poetry Foundation website. To me, poetry is an artistic and creative medium that is intimate. This brings up the question, do you perceive your work as poetry, particularly since you intentionally wanted to rid it of any intimacy?

Sable Elyse Smith: Writing and language were my first introduction to any kind of artmaking or creativity, so in that sense, language has always been crucial to me, and it’s the lens through which I think about physical objects and materials. The thing that’s important and beautiful about poetry, lyrical fiction, or anything that has a poetic tendency is the effect. Poetry creates images, it has a sonic quality, and it’s something that lingers. We might argue that there’s a layer of abstraction in poetry. The abstraction is potentially in what we’re able to understand through language, but poetry is working on different registers, which is something I’ve always been attracted to, and it is through that sensibility I create work. Sometimes, that work directly engages language and thinking through these elements, motifs, and methodologies of trying to transmit information, but other times, it’s through pure colour, line, shape, or redaction. I’m also thinking about when the subject of an artwork can be revealed. Some things are immediate and in your face, while others are slower. I think of that as a poetic device, which I think is present in the Coloring Book series. There’s language there that is important and powerful for what’s beneath it. That’s one thing I want to highlight, which is why I don’t change the information the book came with. I may cross out or add something, but ultimately, I want the viewer to know this exists and show them what needs to be paid attention to. Also, the decision to use oil sticks or oil paint in general and to blow up the scale and manipulate these bright and visibly pleasurable and seductive colour schemes or mark-making is to lure people in. Once you get there, there’s a horror that unfolds at a different timeline.

KM: I’m glad you brought up your use of oil sticks and pastels because they feature prominently in your colouring book pieces. These mediums are typically known for their permanency which made me think of their similarity to the permanency of the carceral system, not just for the people who are incarcerated but for the family members outside and the enduring injurious experience. There are other mediums like watercolour or graphite that could be used that are far more forgiving. Was this something you thought about in your decision to use oil sticks and pastels?

SES: The pieces are like conceptual paintings because they have paint on them, but I’m not a painter. My interest is not in the typical questions and theory of making a painting. I enjoy that in my free time, but it’s not the work that I’m interested in making. For me, the mediums became a perfect vehicle for this found object, these images and texts. There were a couple of decisions that perpetuated that conceptual logic. One was making them a series. The seriality of it feels important to me. Sometimes, people will ask, “Is there a moment when this series ever stops?” My response is yes, but right now, I don’t feel like I’ve exhausted all the potential of it. Also, using these mediums and these objects that are directly talking about the criminal justice system which is insistent; it is something that is serial. I’m interested in the exhaustiveness of this, the repetition of these images. The fact that this is a series and there is repetition ties into the first step of the process—screen printing, which is about mass production. It’s this other industry that is about the perpetuation of something and distribution, reminiscent of its original colouring book form. It’s not just about this one image that exists; it’s about the fact that there could be a million of them out there. If there isn’t a million of this object, there’s a million of another being continuously reproduced and distributed. The scale is also important in the means of production, the enlarging of the colouring book pages.

Then there’s the paint, which in the art context is given the ultimate value, economically and intellectually. I’m interested in the cheekiness of that. I’m not trying to make something beautiful; the way I apply the paint is actually quite crude. I am using seduction as a camouflage to ground people. I continue to use them because there is that kind of hand action, and by using oil sticks, there is this frenetic energy and an immediacy that you have to use to produce them. I’m not taking the time to break down the pigment and mix it. There’s a limitation.

KM: You’ve said that in Fairgrounds, you will have new neon text pieces, colouring book pages, and photographic pieces. In previous exhibitions, you’ve also had video art installations. Is that something that will be present in this show?

SES: Potentially. There are video elements that I’m playing around with. I’ve only visited the gallery a few times. I’ve mapped out elements, and once I’m in the space, I’ll see how things feel. There are smaller video elements I’m playing with, but I don’t know how they’ll end up in the show yet.

At every turn, the coloring book tells children to imagine themselves within the justice system and to constantly erase, shut down, and foreclose imaginations.

KM: Were there any pieces that you were originally thinking of including in the exhibition but ultimately chose not to? How did you decide what to include in the show and how to organise it?

SES: I went through many iterations and possibilities for this show, but I knew early on that I wanted to transform the exhibition space in a very particular way. I conceptualised the show with three elements. I made this jack-shaped (like the toy) sculpture that is made out of prison visiting room furniture and introduced a cream and black colour story. I knew I wanted to do something with that in the show, but magnified. So I came up with vinyl stripes that also reference carnivals and two jack sculptures that are the inverse of this cream and black to hopefully give a sense of disorientation and optical illusion in the space. From there, I built out every other object that will occupy the space. The back room will be visibly neutral. There won’t be frenetic noise present.

KM: That’s amazing. So visitors have to negotiate with the loud pieces in the front room before they find quiet. I’m also interested to hear how you see these pieces located in relation to and in conversation with your previous work.

SES: One thing I’m always intrigued by is exhibition-making, not making one-off objects. I’m interested in seeing objects juxtaposed and in conversation with each other and potentially creating something more tense or sharper than the object on its own. I view this show as works in a similar way to how we think about music, like a chorus or refrain. Some of the subjects are similar, but some diverge and go on their own tangent narratives or get more specific. There’s a building refrain that is a crucial container for the song. I think about the idea of a chorus a lot, which is in music and various forms of literature and poetry, but it also becomes a visual cue for some of the works in the show.

KM: A question that keeps coming to mind is, how do you see the Coloring Book series answering the efforts of defined police departments and abolishing the carceral system?

SES: There are a lot of different answers to it, but the first thing I think about is that art objects exist in a specific context, an art space or gallery that certain people will see. Some objects exist in other spaces that have access and potential for other types of audiences, but knowing and being aware of what that audience will be is also being aware of what an art object can do. It can communicate an idea or information, it can shock or provide tension. That’s one thing that I’m more interested in in my work. I want people to be rubbed the wrong way because those that are, that is, the information they’re getting, that’s material and art within itself. There are a lot of ways that I’m invested in engaging in politics, and I feel like articulating my point of view through object-making is one thing, teaching is another, and being in dialogue in intellectual spaces is another. I’m very careful about conflating what either of those aspects can do. I often get the comment that I’m an activist artist. My art practice is not activist. Certain things I do in my daily life as a human being who is engaged in certain communities and conversations might look like activism in some aspects. I participate in different ways. Those distinctions are important.

Written by Karla Méndez