Irish-American artist Michael Craig-Martin is known as much for his vividly pigmented studies of banal objects as he is for his earlier conceptual installations—in 1972 he famously proclaimed that a glass of water was an oak tree, simply because the artist said so. In considering the language of objects, he has broken down the very fabric of material identity to create works that speak a universal tongue and question how we interpret what we see. For his new show in Florida, he has brought together painting, printmaking and sculpture for the first time, in one of his biggest US shows to date.

As an artist you were born in Ireland, raised in the States and made a home in the UK, what do you consider to be your national identity?

It depends what country I’m in! I was born in Ireland, but I never lived there, though I do feel a strong connection to my family as I spent a lot of time there as a child, with my grandparents. There’s part of me that does feel distinctly Irish, though in a way my gut instinct is American—but I’ve spent by whole adult life in Britain. Theresa May said something terrible recently: “If you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere,” and I felt a knife go through my heart. So many people have the same sense as me, that they belong to the world, and have associations with more than one country.

What did you learn from going to Yale in the 1960s to study art? It must have been a very formative time.

I was very, very lucky. I started Yale in 1961 practically by accident, and when I arrived there were so few undergraduates studying painting and sculpture that we were just put in with the graduate students, with no programme. I was in the same class as Richard Serra and many other extraordinary artists were there too, like Brice Marden and Chuck Close.

Of course, don’t forget this was the sixties and Yale is not that far from New York, so I saw most of the early Pop Art and minimalist shows, all of the colour field painting… Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, I saw many of their key shows as a student. You can’t get a better start than that.

Those influences are clear, but there’s also an incredibly potent use of colour in your work, that has only appeared in more recent years.

I was frightened of using colour for a long time, it is quite daunting. I wasn’t until later in my career that I stumbled on it, which came from doing installations. I did one in a gallery in Rome and the building was old and full of character, not a white cube at all. For the first time I painted the walls in colour, and my life changed forever.

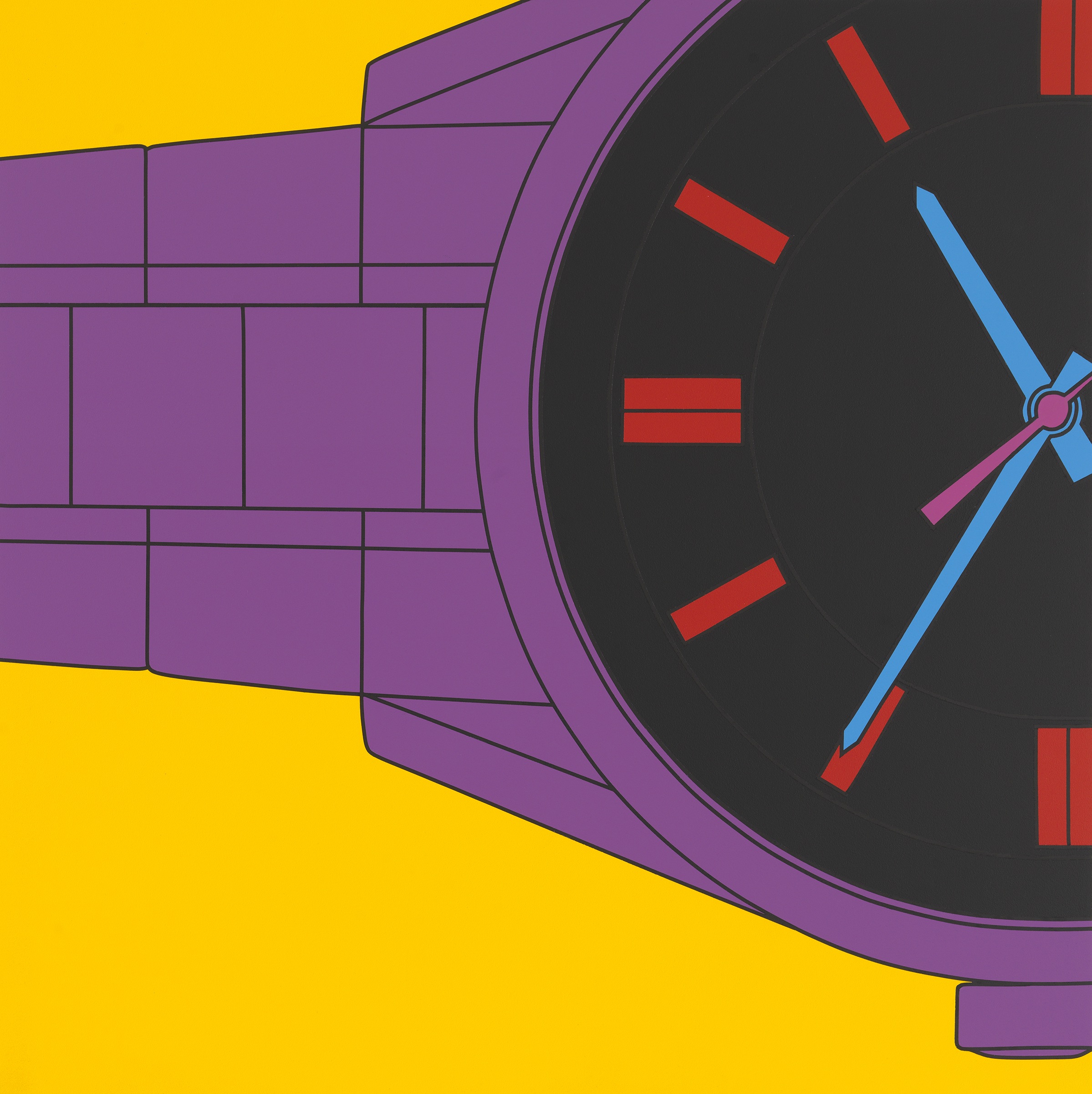

In another gallery in Paris I painted all the seven rooms a different colour: red, yellow, blue, purple, magenta… and I thought “how many different colours are there? Not that many!” I used every colour at its most intense and I used ordinary house paint. People came in and had a response of pleasure and astonishment that I’d never seen towards my work before. That led to me putting colour into my images.

Is there a parallel with the way you use colour and depict objects?

I never draw an object that you can’t name: chair, table, shoe, book. I would never depict an object that would make you speculate as to what it is called. That is why my idea is: if it doesn’t have a name, don’t use it. I never mix or use special colours, they come out of the tube. Somehow, I’m told my colours are special, and I can’t work it out. Whatever I do with it, it seems to be different. One of my teachers at Yale said “Remember, you don’t have to use all the colours at once,” but boy, was he wrong.

You have millions of objects to choose from as your subject, what is the process of selection?

When I started drawing them all I thought, “I’m going to be here forever, there’s millions of objects.” But actually, there aren’t. I drew everything I could find, around 500, because 95% of things are a repeat of another object. If you say chair, there might be thousands of chairs in the world, but “chair” still means “chair”. It’s amazing, the limited number of objects that define our world.

About ten years ago I realized that objects were changing, and through drawing I had been charting that change, which is reflected in this exhibition. I wanted to start drawing things that are both temporary and thoroughly contemporary, such as iPhones, laptops, memory sticks and sat navs, all the things we use that are actually very expensive, yet ubiquitous. You can’t say that something “ordinary” relates to it being modest anymore.

For most of the twentieth century we followed the mantra that form follows function, that it looks like what it does. As soon as we get into the technological age, that idea has gone out of the window. An iPhone doesn’t look like anything, but it holds fifteen other objects. Personally I’m very interested in two-dimensionality. My sculptures are drawings, they aren’t sculptures of things, they’re sculptures of images of things, and so you read them as two-dimensional. That play between my object and the reality is very interesting.