Absurdism Ahoy

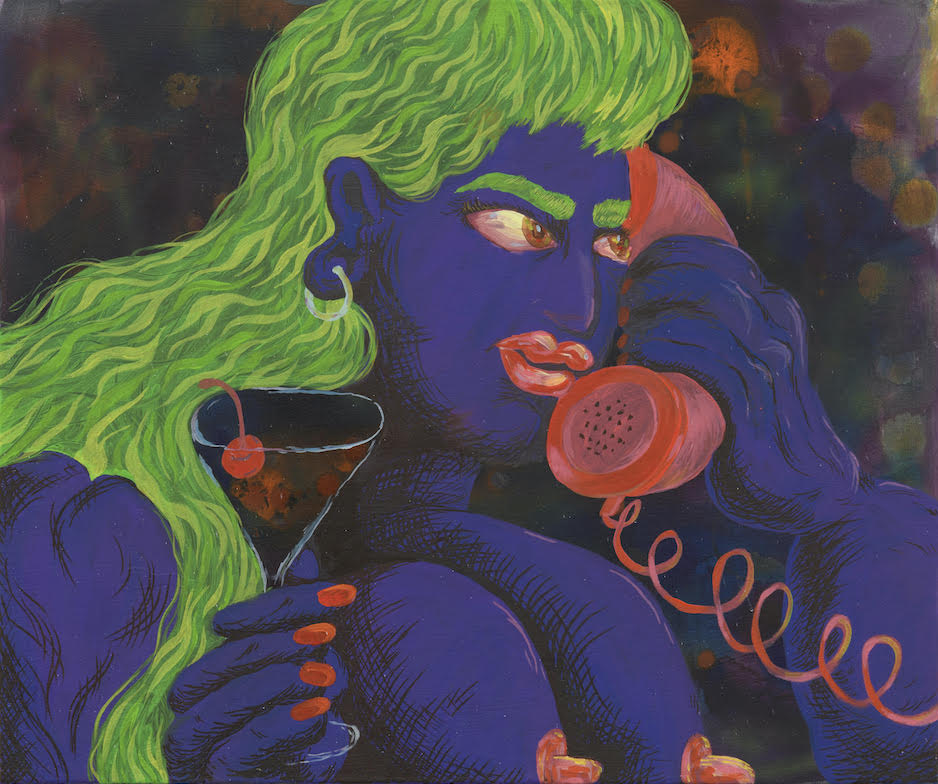

We just can’t resist searching for meaning in a world while knowing we won’t find it; culture thrives on this paradoxical human tendency. In 2021, Absurdism in art will play out in everything from photography (the likes of Instagram favourites like Alexandra Von Fuerst, @smeccea, Balarama Heller) to painting (take a look at what Ana Benaroya, Kate Groobey and Henni Alftan are doing, among others) to public sculpture (as seen in a 33-metre-high vulva sculpture installed on a hillside in Usina de Arte, Brazil by artist Juliana Notari, revealed earlier this month). Since a lot of the work we’ll be seeing in 2021 was created during multiple lockdowns and under conditions of confinement, it’s no wonder it will recognise this conflict between purpose and pointlessness, a push and pull between fun and futility. Or you could just watch Emily in Paris and realise that actually there is just no meaning to anything anymore. (Charlotte Jansen)

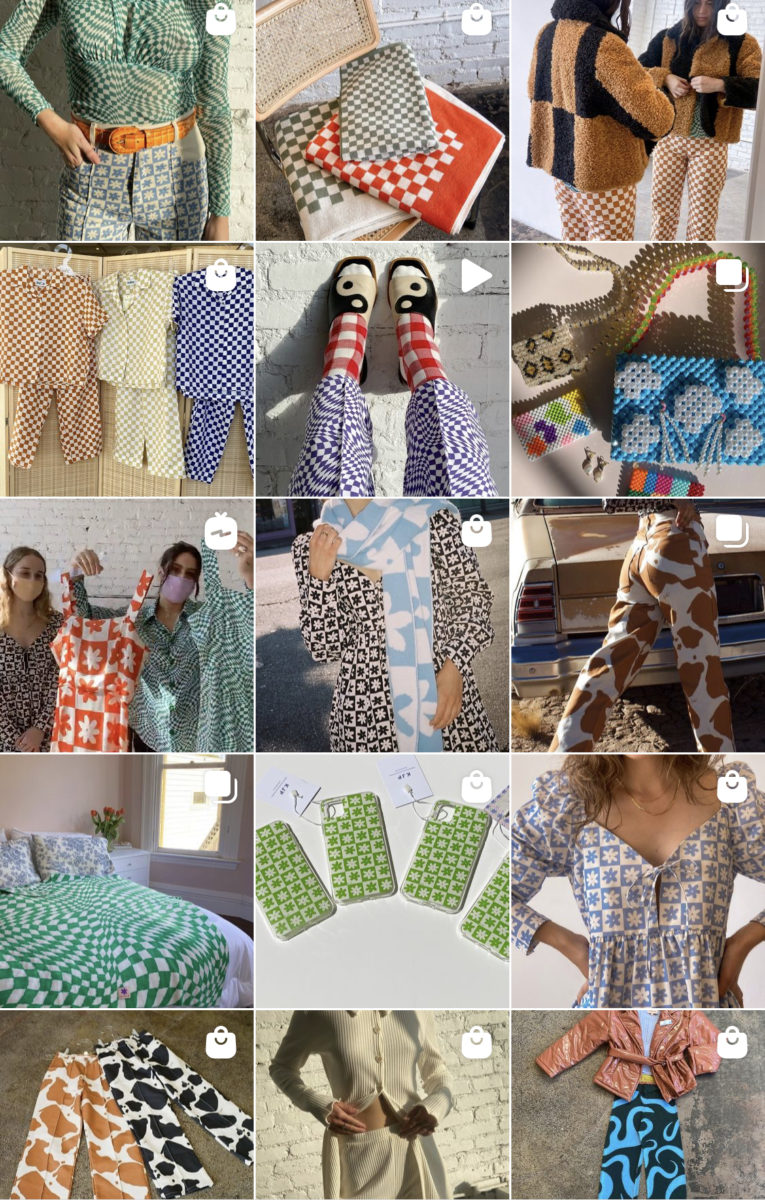

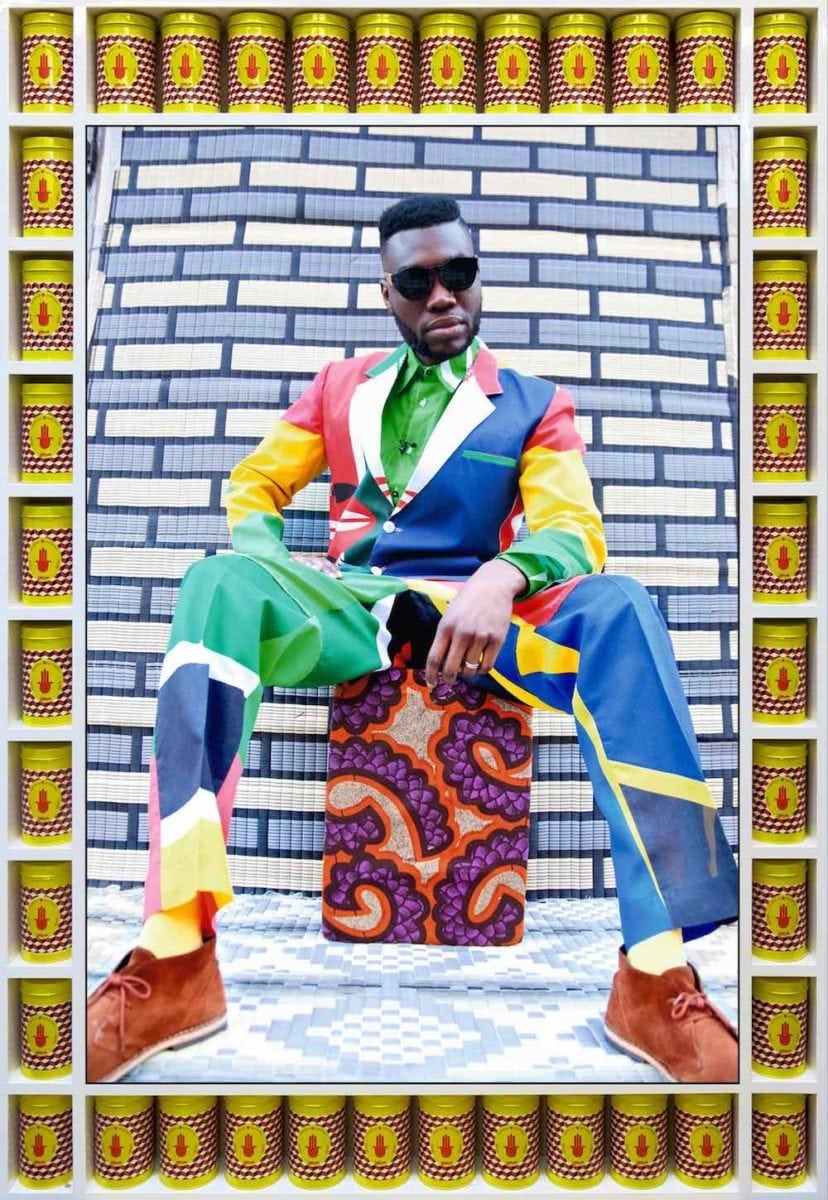

- Left to right: Instagram page of Lisa Says Gah. Nathalie Du Pasquier, Gabon, 1982. Photo: Studio Azzurro. Courtesy MK Gallery. Hassan Hajjaj, Afrikan Boy Sittin’, 2013/1434. Courtesy the artist and Arnolfini

Postmodernism for Millennials

Where blonde wood, natural materials and Scandi stacking school chairs previously reigned supreme when it came to aspirational interior design, the latest millennial design trajectory is definitively maximalist. Terrazzo flooring, rainbow taps and geometric tiles (think Anthea Hamilton’s Squash takeover at Tate Britain in 2018), and lots of pastel shades of pink, purple, green and blue. It continues the trend for all things 70s-inspired, kickstarted in the fashion industry by Alessandro Michele’s Gucci, and sees a resurgence of the wayward whims of postmodernism trickled into everything from garments to rugs to chairs. A major exhibition of Ettore Sottsass’ Memphis Group, up at MK Gallery until April this year, adds further fuel to the flames, as does Hassan Hajjaj’s exhibition at Arnolfini. The consumer end of the trend has been nicknamed “avant basic” by former Dazed fashion editor Emma Hope Allwood for its inherent contradictions, offering a quirky fantasy to a mass audience, or “algorithm fashion”, via the likes of fashion retailers Paloma Wool and Lisa Says Gah, where bright, clashing prints and chunky heels reveal the evolution of the likes of Marimekko and Celia Birtwell for a firmly millennial audience. Move over modernism, postmodernism is back. (Louise Benson)

Goth, Monochrome Graphics Are Out (for now…)

It’s an aesthetic favoured by the likes of modular synth nerd-baiting Berlin arts festivals, techno record labels, pop-up t-shirt stores and the kind of subtly edgelord-leaning male art directors who spend a lot of time on Instagram. Black, white, occasional shades of grey; all-caps, widely spaced, sparse serif fonts; some sort of scientific illustration or geometric patterns. Such designs have, to their designers’ credit, been largely successful; hence their perennial status throughout the 2010s. However, just three letters has changed all that: CIA. The US federal agency recently launched new designs that pilfer that trendy design language and take it to its logical conclusion: the very opposite of what it’s supposed to signify. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the new CIA brand and website design—which aims to appeal to young recruits with its hip vibe, monochrome palette and fonts like Grilli Type’s America, more usually associated with the hip young design crowd than national security—has got itself a fair few detractors. Designer David Rudnick said that “with this rebrand, the CIA has lost all credibility”; while some on Twitter compared the new logo’s line-based graphic (alluding to data and sound recordings, apparently) to Peter Saville’s iconic sleeve design for Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures. (Emily Gosling)

Chiharu Shiota’s new installation at König Galerie

A Need for Repair

Over the last couple of years, there have been countless exhibitions about the damage that humans have done to Planet Earth. The visibility given to environmental issues by these shows has left audiences in no doubt: the world is at breaking point. Recently, there has been a noticeable shift in focus towards possible solutions. While Moma’s Broken Nature has a less-than-positive title, it hones in on innovative and creative ways of turning things around: from regenerating coral reefs to the concept of restorative design. The show examines “how design and architecture might jumpstart constructive change”. Olafur Eliasson’s very successful In Real Life continues at a pace this year, opening at Guggenheim Bilbao in April with a keen focus on the artist’s experimental environmental work. A message of optimism is also present in Chiharu Shiota’s new installation at König Galerie, which shares stories of hope from around the world. “In contrast to the opacity the pandemic has suddenly catapulted us into, here it is the principle of hope that’s in charge,” writes the gallery. Even David Attenborough’s recent, sobering Perfect Planet concluded its episodes with a focus on initiatives which could move the world towards a cleaner, more positive future. (Emily Steer)

Typography Goes Back to the 1970s

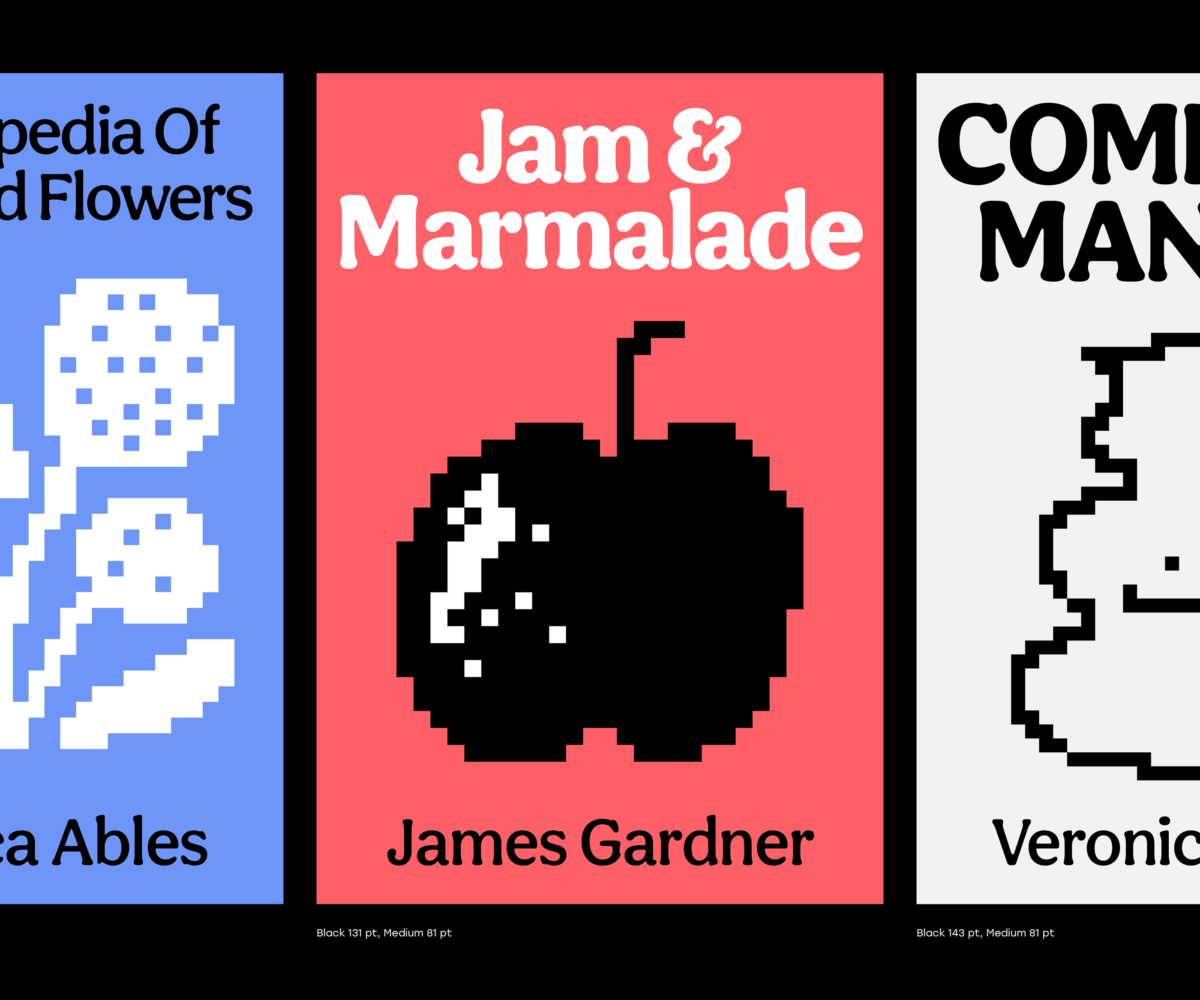

In Burger King’s first rebrand in 20 years, design agency Jones Knowles Ritchie created a very cute, unabashedly retro but also undeniably stylish new logo that directly references the one used by the brand in the 1970s, 80s and 90s. The new bespoke font, Flame Sans, is deliciously 70s in its squidgy, pliable forms and carefree aesthetic. A number of new fonts that are predicted to do very well this year also tread a 70s path: Moranga by Sofia Mohr Latinotype uses similar tones in its promo imagery, and its retro serif letterforms call to mind iconic twenty-first-century type stalwart Cooper Black. That font is also referenced in Aesthet Nova, a display serif type family designed by Mariya V. Pigoulevskaya and released through The Northern Block this January. It’s perhaps a more subtle nod to the 70s; while Bogart is unashamedly vintage. Designer Francesco Canovaro, who published it through Zeta Fonts, created it as a typographic tribute to low-contrast, old-style fat faces like Cooper Black and Goudy Heavy Face, and its playful, hippie-ish vibes suggestive of simpler times, with their hints of 60s and 70s rub-on transfer designs and phototypesetting systems of the 1960s and 1970s, and are bursting with hippie energy and childlike personality. (Emily Gosling)

- Ajuan Song, Absolutely Augmented Reality. Courtesy Hoxton 253

Extended Reality Gets Another Chance

A few attempts were made to make Extended Reality (XR) cool (remember Bjork’s 2016 exhibition at Somerset House?) in the art world, but without much success. Then the pandemic hit. Galleries, art fairs and institutions alike have little choice but to embrace it, whether it’s using smartphone accessible Augmented Reality technologies to present digital programmes, or via art made using AR and VR tech that can give the viewer the 360 experience in absentia. In the last year, AR has been slowly seeping into our daily lives via social media filters (blame the lockdown boredom). AR is more accessible, affordable and appealing as an artistic medium. AR artworks have proved popular on the much-hyped Acute Art app under the directorship of Daniel Birnbaum, with ambitious projects by established names like Oliafur Eliasson and Cao Fei (whose VR experience was shown for a few days at the Serpentine Galleries in 2020 before moving to the Acute Art App). Jenny Holzer launched her big AR public art project “You Be My Ally” with the University of Chicago last year. More AR art is sure to follow in their virtual footsteps in the near future. Of course, you can also experience AR IRL: in summer 2021 American filmmaker, writer and artist and Chinese multimedia artist Ajuan Song will open Absolutely Augmented Reality (an AR photo show) at Hoxton 253 in London. (Charlotte Jansen)

Artistic Independence

If 2020 was the year that saw the art-world merry-go-round stop, 2021 is the year that artists take matters into their own hands. The Artist Support Pledge, an initiative started by artist Matthew Burrows as a means for artists to make an informal income via Instagram during the pandemic, has become an international phenomenon, generating millions in sales. More artists than ever before are taking to Patreon, Instagram and YouTube to sell their work and reach audiences (the artist Stuart Semple has run successful lockdown life drawing classes). Michaela Yearwood Dan sold a series of ceramic works via Instagram Stories last year, while Aaron Angell has established an online store in conjunction with his pottery studio Troy Town. Artist-run galleries have also sprung up despite the setbacks of the pandemic, with HOME by Ronan McKenzie, which has a focus on Black artists, launched at the tail-end of last year. This year artist couple Lindsey Mendick and Guy Oliver are slated to open Quench, a project space in Margate, and led a successful fundraising campaign throughout December, offering collectable ceramics and prints as rewards. It indicates a broader trend towards the diversification of what it means to collect art; where there was previously a snobbery around artist editions or merchandise, particularly from gallerists keen to keep prices high, artists have increasingly moved towards direct sales and more creative approaches to their output. (Louise Benson)

Alternate Worlds Arise

2020 was undoubtedly the most unsettling year in recent collective memory, and 2021 has shown no sign of letting up the pressure. It’s no wonder then, that some people are looking for escape. Numerous exhibitions this year explore alternate worlds, spanning utopia, dangerous ideology, and personal escapism. Ad Minoliti has exhibitions at both Baltic and Mass MoCA: the former has been conceived as an “alien lounge”, the latter, Fantasias Modulares, blurs boundaries between human, animal and machine in her characteristically utopian work. The Argentinian artist, who featured in Issue 43 of Elephant, “uses her work to picture alternate realities free of biases by utilising diverse, colourful, and playful hybrid forms”, writes Mass MoCA. At Tel Aviv Museum, Karen Russo’s Myths of the Near Future explores “the failures of personal, artistic or national utopias”. The Israeli artist brings together stories from history and fantasy, moving between science fiction and dangerous ideology. Meanwhile at Istanbul Modern, Selma Gürbüz merges her own fantasy world with the one we live in, presenting “elaborately crafted works woven with myths, legends and fairytales”. (Emily Steer)