One positive take on the current pandemic is that, with many people staying at home, avoiding flights and not consuming quite as much, we are having a positive impact on the environment. This can be seen within the art world right now, as the global flurry of art fairs comes to a halt. Of course, it remains to be seen whether this slowing down will have an impact in the long-term, once free movement becomes more available again.

Historically, art has often presented nature as little more than a passive muse or backdrop. This year was set to see numerous art institutions address the climate crisis through a lens that was more reverential, including London’s Somerset House, Serpentine Galleries and Hayward Gallery, Liverpool’s FACT and the Baltic in Gateshead. Finally, we collectively seem to be admitting our human powerlessness and the fact that we, too, are animals.

- Kuai Shen, Ohm1gas, 2012. Installation view. Photo by Miha Fras. The work was set to go on show at FACT

This emerging angle is beautifully articulated in FACT’s planned show And Say the Animal Responded?, focusing on what animals might actually say, if we were to listen to them. “Art is so important in how we think about the world,” says curator Nicola Triscot, who has a long history of exploring environmental themes through art. Her curatorial stance in this instance was to ask of each work, “Is it coming from the animal’s perspectives?” She adds, “We can only usually think about animals through our own eyes, so it was a difficult process.”

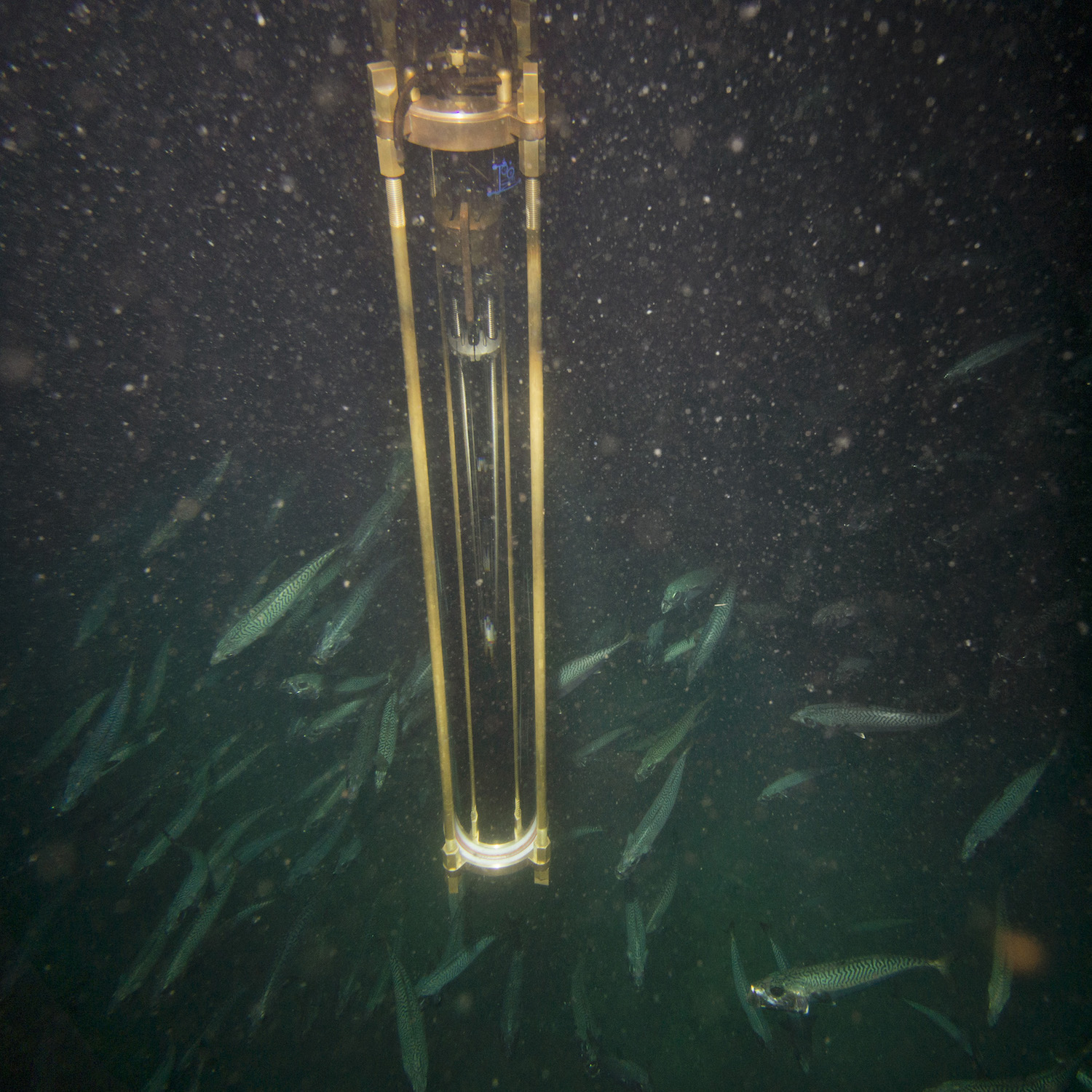

One of the key works due to be featured was a new installation by Mexican musician and artist Ariel Guzik. The piece incorporates sound, drawings and sculptural works from his long-term research project, which sees him communicate musically with whales and dolphins in the wild using his instrument, Nereida. This is submerged in the deep sea and uses subtle vibrations that invite a chorus of responsive sounds.

“We can only usually think about animals through our own eyes”

“He’s sending a message of love into the oceans,” says Triscot, who explains that while huge vessels disrupt and stress ocean creatures, his work has the opposite effect. Sea mammals are intrigued by the sounds, and are attracted to it. This is scientifically evidenced by their vocal responses, which Guzik presents alongside the recordings from the vessel with which he “spoke” to them. “We’ve changed animals’ worlds and we aren’t seeing it as an issue,” says Triscot. “Why don’t we think about things from the animals’ point of view, when we talk about their tragedies? It’s not just about ‘Isn’t it a shame that we can’t get food from the bees.’ Or ‘The coral is now bleached so we can’t scuba dive.’”

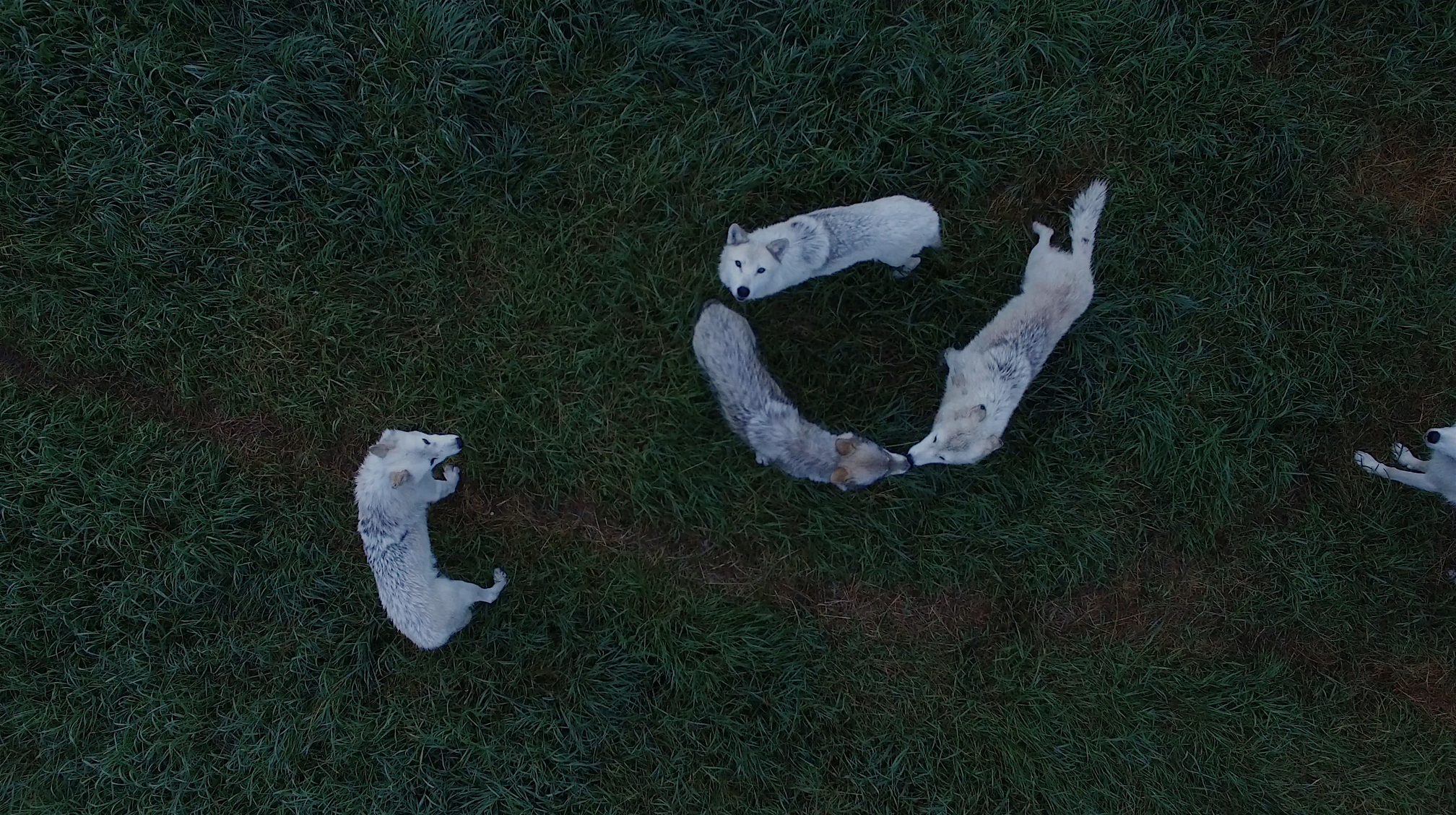

In late 2019 Baltic opened Animalesque / Art Across Species and Beings, curated by Philippa Ramos and featuring artworks spanning film, video, drawing, sculpture, installation and sound art. The show invited visitors to rethink the human position in the world in relation to other species, and the “complex ecologies that bond beings together”. The idea was to push a non-human-centred perspective, and consider “non-verbal forms of communication”, says Irene Aristizábal, head of programmes at Baltic. “It brings behaviours in the animal world to the fore, which tell us about how we behave ourselves.”

This movement for art to centre on animals’ rather than humans’ voices might have an interesting foundation in the concurrent conversations around gender identity. Aristizábal suggests these shows are not only springing from an increased awareness of climate change but also the “influence of feminism in terms of how we relate to our cities”. She cites writers like Donna Harraway, who artists seem to be referencing more than ever. “We are animals too, and the show looks at hierarchical perspectives, but also at future and gender perspectives. The performativity of gender is a human construct, and it can be interesting to see the realities of the animal world, in how sex and other kinds of relations happen. We need to demystify how these binaries were constructed.”

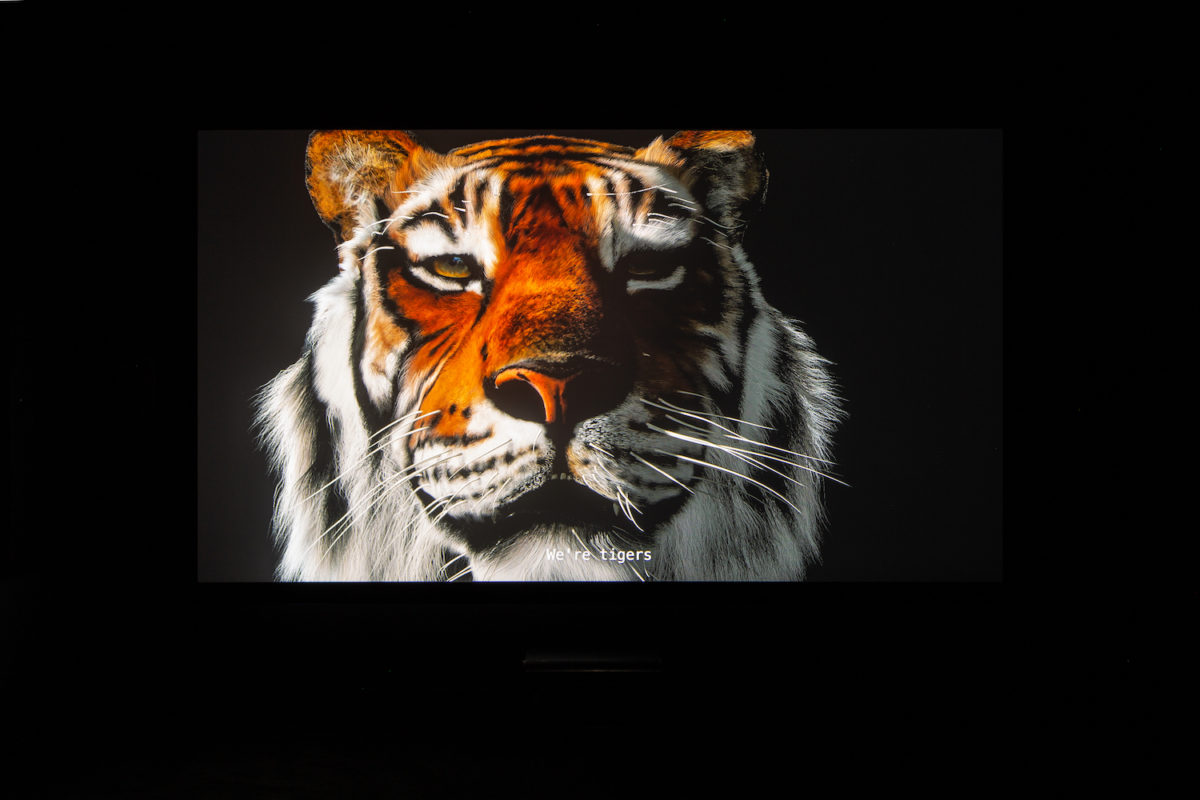

- Ho Tzu Nyen 2 or 3 Tigers, 2015. From Animalesque / Art Across Species and Beings, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, 2019. Photo by Rob Harris © 2019 Baltic

“It’s moving away from the idea of hierarchies where humans come first,” she says. “There’s a wider consciousness around how we relate to the natural world. Ecofeminism [a branch of feminism that draws on the concept of gender to analyse relationships between humans and the natural world] is grounded in that and has an important impact on artists’ approaches.”

Animalesque was still running when a new Baltic exhibition of work by Abel Rodríguez, an indigenous Colombian elder who paints the landscapes of his birthplace from memory, opened last month. His works were also shown as part of the Hayward Gallery’s group exhibition Among the Trees. Billed as “the first comprehensive exhibition in the UK exploring trees and forests in contemporary art”, the show (which is currently on hold while the gallery is closed) includes work by thirty-eight international artists, created over the past fifty years. Steve McQueen shows a photograph he took just outside of New Orleans of a tree once used as a gallows for racist lynchings, one of a number of pieces that “cast trees as silent witnesses of forgotten histories”, as Hayward puts it. Rachel Sussman’s colour photographs show some of the world’s most ancient trees, one of which is 9,500 years-old. Other artists include Tacita Dean, Peter Doig, Kazuo Kadonaga, Luisa Lambri, Myoung Ho Lee and George Shaw.

- Abel Rodríguez, Terraza Alta, 2019 (left); Orilla de Rio, 2018 (centre); Terraza Alta III, 2018 (right). Courtesy the artist and Instituto de Visión

Hayward Gallery’s director and the show’s curator, Ralph Rugoff, says that Among the Trees aims to leave visitors with “a renewed sense of appreciation for both the beauty and complexity of these indispensable organisms”. In the show, trees are presented as natural, physical wonders, and symbols in art that have shaped human civilization, our collective ways of living and our imaginations. The three sections of the show look at nature’s “complexity and connectivity”, loosely echoing the recent news about the “wood wide web” concept that roots, fungi and bacteria are intertwined to create a sort of subterranean social network; the blurring of nature and culture today; and the theme of time, examining the seasonal changes and trees as a symbol of mortality, beings that often live far longer than humans.

“Having a connection with the cycles of the seasons and the weather, means having a connection with ourselves”

The interconnectedness of the natural world and humankind, and nature’s largely unseen power over our lives, are notions that seem particularly apposite at the moment, as the world is brought to standstill. It suddenly has become very apparent that however advanced we may like to think we are as a species, when you mess with nature, things go very, very wrong (the overarching theory of COVID-19’s origins traces the virus to bats). Arts and social justice project Idle Women was founded around principles of co-creation and collaboration within complex sociopolitical contexts, and largely works outside formal institutional settings on projects that reconnect people with the natural world.

Founded in 2015, Idle Women’s recent projects have included a collaboration with support service organization Humraaz, and gardener, writer and presenter Alys Fowler, who’s helping to create the UK’s first medicinal herb or “physic” garden for women and girls on the Leeds to Liverpool Canal. The goal is to provide a “living archive of women’s medicinal plant knowledge” and work with women to design, landscape and plant a 2,500 square-foot site near the Selina Cooper, Idle Women’s narrowboat HQ.

Rachel Anderson, co-founder of the platform, formerly produced collaborative projects for ArtAngel, while her partner Cis O’Boyle was a theatre maker and lighting designer for sites including the Royal Opera House. They found themselves increasingly protesting the closure of devoted women’s spaces, such as Lambeth Women’s Centre. “We both felt like we could use our skills and access in the arts to feed in more constructively to the women’s sector,” says Anderson. “We became really interested in sustainable spaces for women that can’t be taken away.” Hence the narrowboat, which can access more people on a local level and doesn’t carry such risk of being “taken away” as landlocked sites.

- Left: Allora & Calzadilla, Hope Hippo, 2005. Courtesy the artists. Right: Pierre Bismuth The Jungle Book Project (2002) Courtesy the artist and Jan Mot Gallerie. Animalesque / Art Across Species and Beings, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art 2019. Photo by Rob Harris © 2019 BALTIC

The project offers women who might not have access to natural areas and gardens the chance to experience and work in them. “It’s so important for women, especially, to have access to nature,” says Anderson. “Having a connection with the cycles of the seasons and the weather, means having a connection with ourselves.” This connection between women and the natural world directly informed the physic garden: from its site, you can see Pendle Hill, which is most famous for its well-documented 1612 witch trials. Such demonizing attitudes towards women significantly contributed to a “severing of knowledge and power for women which we’ve still not recovered from”, according to Anderson. “We’re connecting back to the roots of community knowledge around plant medicine, knowledge which was taken out of women’s hands.”

It’s interesting how often women’s voices, art and nature converge, whether that’s in the ecofeminism that Baltic curator Aristizábal cites or the collaborative, participatory nature of Idle Women’s projects. Many studies have shown that women are making the most active steps to rail against climate change, with Greta Thurnberg recently becoming the straight-talking face of the youth movement. Of course, this current wave of exhibitions have featured artists of all gender identities.

- Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, The Substitute, 2019. Courtesy the artist. The work was set to go on show at FACT.

With the pure number of shows planned, you do have to wonder if this is trend-driven. “I hope it’s not just a fashion,” says Aristizábal. “I think there’s a growing consciousness around how we deal with the natural world and the planet, and an explosion of that subject matter is being explored in artistic practice,” she adds, citing personal wellbeing and the realization that the planet isn’t exactly in the best shape as possible reasons. “It’ll become harder, even for people who don’t work politically, to not consider the impact of art production and commerce on the environment. It’s important that institutions view this as an important way to open people’s minds, or offer a counter narrative to mainstream culture and media. We need to change the way we think about and relate to the natural world, and realize that it’ll come to an end if we don’t stop using fossil fuels.”

And it’s high-time we did. Crises such as the current pandemic and climate change shouldn’t just be headline-fodder, but agents of change which, like art, help us wake up and reconsider things. We are just animals, after all, and now we’re all fighting for survival in an ailing world.