It might seem slightly on the nose for Frieze London to present a curated section called Possessions. After all, the end game of an art fair is to sell as much as possible, even if the whole thing is happening online this year. However, in the hands of curator Zoé Whitley, the term takes on a two-fold meaning. “It is a bit of an in joke, because possession relates to a state of owning,” she says, “but there is a double meaning. It also relates to the notion of being controlled by a spirit or being dominated by an idea.”

She focuses on this more expansive reading through the work of artists who—rather than conveying literal interpretations of organised religion or relying heavily on the iconography of faith—explore how art can connect with or convey something transcendental. The idea was sparked by a quote from the late artist Noah Davis, who declared that “painting, like spirituality, makes people very uncomfortable”.

It is fair to say that the art world, at least in the contemporary sense, has kept spirituality at arm’s length. Prevailing narratives have often minimised the impact and influence of something metaphysical, or even exoticised and othered the connection. That is why it is so refreshing to see such a range of work presented in this section, which celebrates the relationship with solitary and collective spiritual experience.

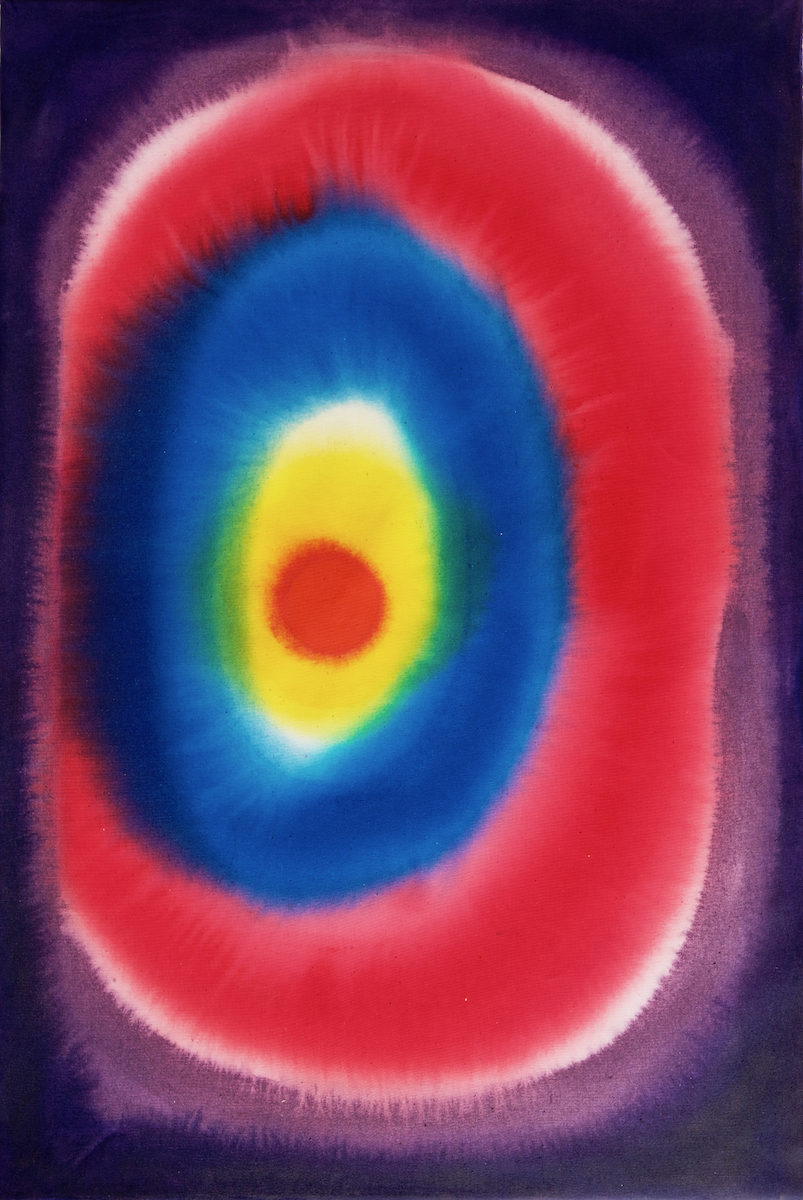

Unsurprisingly, painting features heavily. Mike Cloud‘s expressive pieces expand the accepted notion of portraiture, while Prafulla Mohanti‘s tantric works take the form of vivid circular formations that are informed by his childhood in a remote village, where he was often called upon to draw near-perfect circles for special occasions including religious celebrations.

“Technology has been all but deified, and the relationship between body, mind and soul has been irrevocably altered”

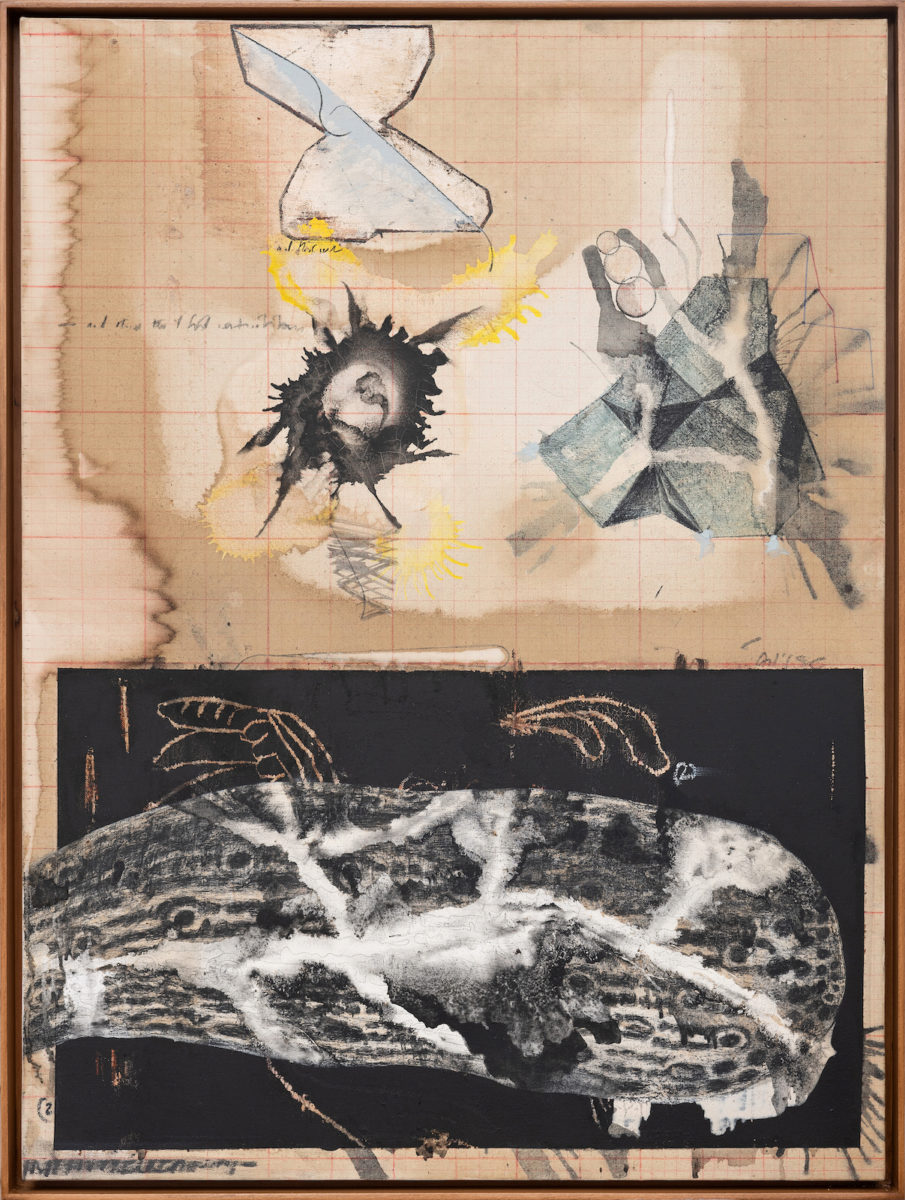

Buhlebezwe Siwani also interrogates the cultural significance of spirituality and ancestral ritual. Her abstract paintings incorporate green soap, thereby considering the habitual act of cleaning the body. As an initiated sangoma—a traditional healer that works within the space of the death and the living—she also probes the relationship between Christianity and African spirituality, using performance, sculpture and photography to question the history of colonialism and bodily agency.

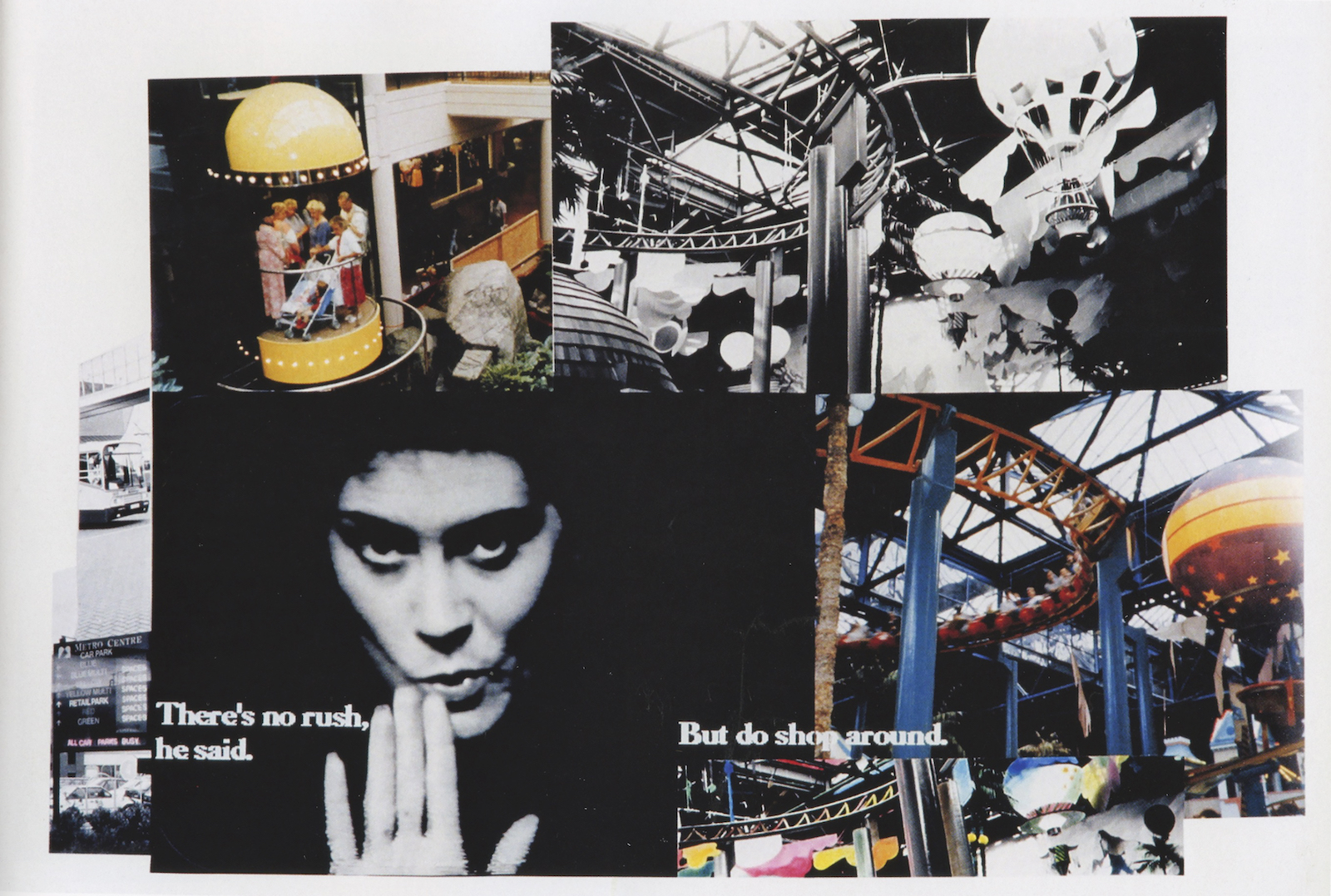

Meanwhile, in the work of Vera Frenkel, the association between religion and contemporary commerce is pulled apart. The Canadian artist has been making video works that encompass text, sign language, performance and more, since the 1970s, in what Whitley describes as an “exploration of consumerism” and a study of “the seduction of aspirational buying”. Some 50 years later, technology has been all but deified, and the relationship between body, mind and soul has been irrevocably altered.

While Frenkel’s installations are ominously prophetic, Veronica Ryan’s subtle, sensitive sculptures consider the power of everyday objects and the spiritual impressions they can contain. She utilises innocuous objects such as food packaging and agricultural ephemera to build various totems that speak to issues of memory, migration, displacement and loss. Each piece appears both familiar and mysterious, much like the nature of spirituality itself.