Hank Willis Thomas and Emily Shur, Freedom From Want, 2019

There is no denying that Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms—a visual interpretation of President Franklin D Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union address—shaped the face of US visual culture. Illustrating the fundamental rights of “freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear”, they cast a view of an idealised America, but one which was entirely white. In 2018, Hank Willis Thomas and Emily Shur reimagined these images, under the umbrella of the politically active artist collective For Freedoms (a canny take on the original name). They photographed scenes of a multicultural society that includes artists, activists, public figures and more. Not content with four views, they created 82, all of which present a more accurate account of the country’s modern-day makeup.

Danh Vo, We The People, 2011

We the People is a 1:1, minutely detailed replica of the Statue of Liberty rendered in exactly the same thin hammered copper as the original frame Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi made for the Statue of Liberty in the nineteenth century. The aim for the project was to “turn something familiar into something very unfamiliar” Vo said, by dismantling the statue and laying it bare, in pieces, across the gallery floor, revealing just how delicate the monument really is, both materially, and as a synecdoche for American freedom and resilience.

Kent Monkman, Welcoming the Newcomers, 2019

Kent Monkman is a Cree artist who turns the narratives of colonisation across Canada and the United States on their head. In Welcoming the Newcomers, he envisages a scene which mirrors the composition of Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, alluding to its narrative of shipwreck and starvation through the context of the “wooden boat people” who arrived on North American shores. The painting presents Monkman’s gender-fluid alter ego Miss Chief Eagle Testickle as the central figure, who extends a life-saving hand to an enslaved African man while conquistadors and Puritans struggle to gain footing on land. The work was one of two commissioned for The Met’s Great Hall, in an effort to reassess the stories that are venerated throughout its historical collection.

Harmony Korine, Spring Breakers, 2012

On the face of it, Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers—the director’s shiny, blingy 2013 dark comedy—is all boobs, beaches and babes. But you barely have to scratch the surface of the Florida-based vacation-romp-gone-bad to see its searing, scathing attack on the modern day American teen dream. Much of the film is unflinchingly grotesque, dialling up its hot young cast’s sexuality to nigh-on pornographic proportions. The film’s anti-hero of sorts—a rapper, drug-pusher and arms dealer going by the name Alien—arguably embodies everything that’s hideous about modern interpretations of American-ness: he describes his life as the “American Dream”, in between ogling young girls, waving around dollar bills and apparently giving a gun a blow job. It’s ludicrous and hideous at equal turns, a high-octane, brash performance of “too much of a good thing”; a sardonic commentary of the disconnect between performative fun, freedom and the real-life horror of what that often entails.

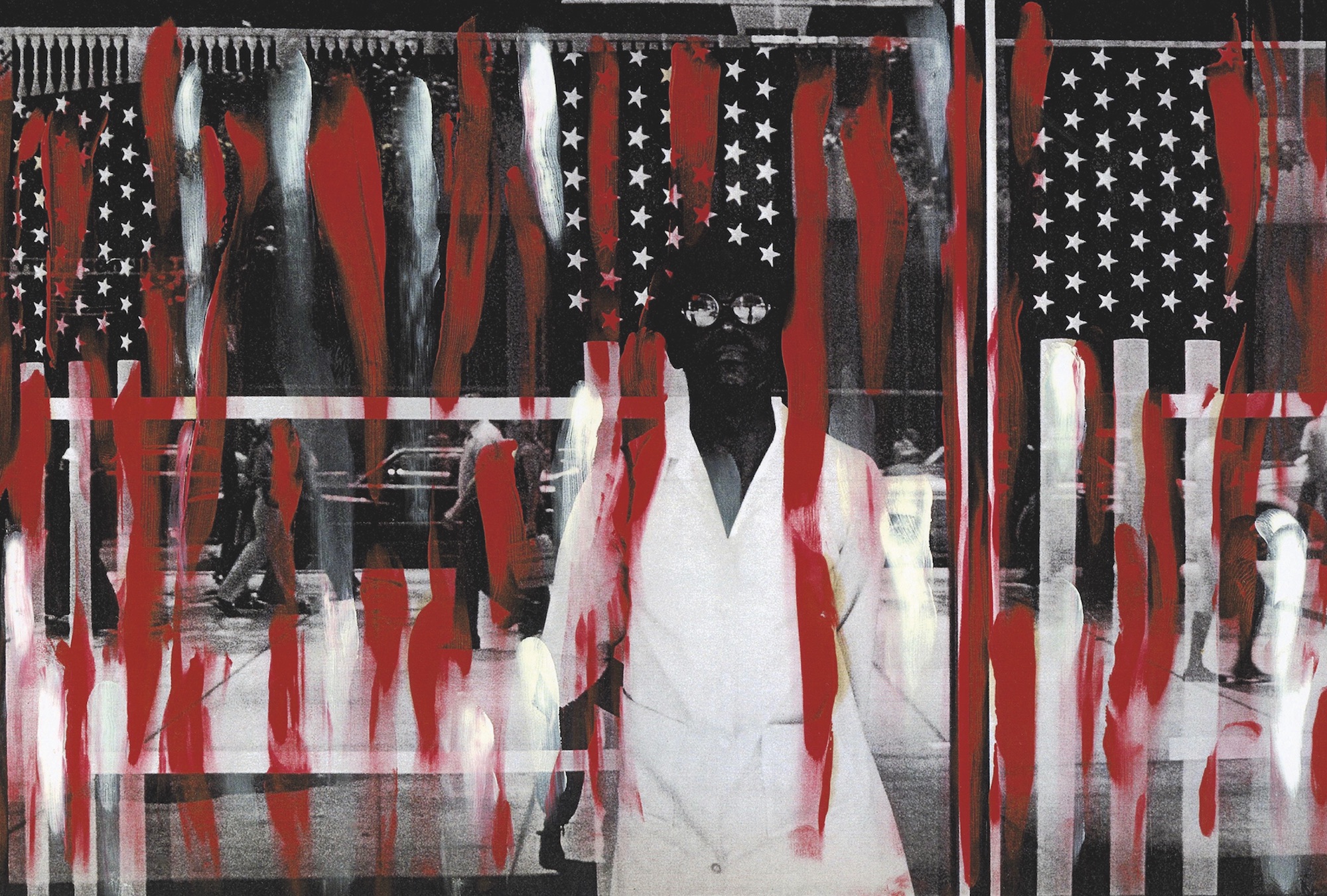

Ming Smith, America Seen Through Stars and Stripes, New York City, New York Painted, 1976

The red paint trickling down the hazy photograph might be the marks of defiance, its subject turned to face the camera head-on in mirrored sunglasses, or these wild streaks could be a symbol of the turbulence that defined America during the 1970s. Through Ming Smith’s overlaid hand-painting, the stripes of the national flag appear to unfurl and break apart, much like a country bitterly divided over questions of race. Smith was the first female African American photographer to have her work in the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and the first female member of the photography collective Kamoinge Workshop, a group of New York-based black photographers founded in 1963. Yet she has only recently been more widely recognised as a photographer and artist, with her first monograph released this month by Aperture. Her focus is on the racial politics of America, with her hazy black and white photographs of everyday encounters often transformed by double exposure, collage and layers of paint. As she stated in an interview this year, “I guess in my world I just go for things regardless of the boundaries, because I’ve always had to break boundaries.”

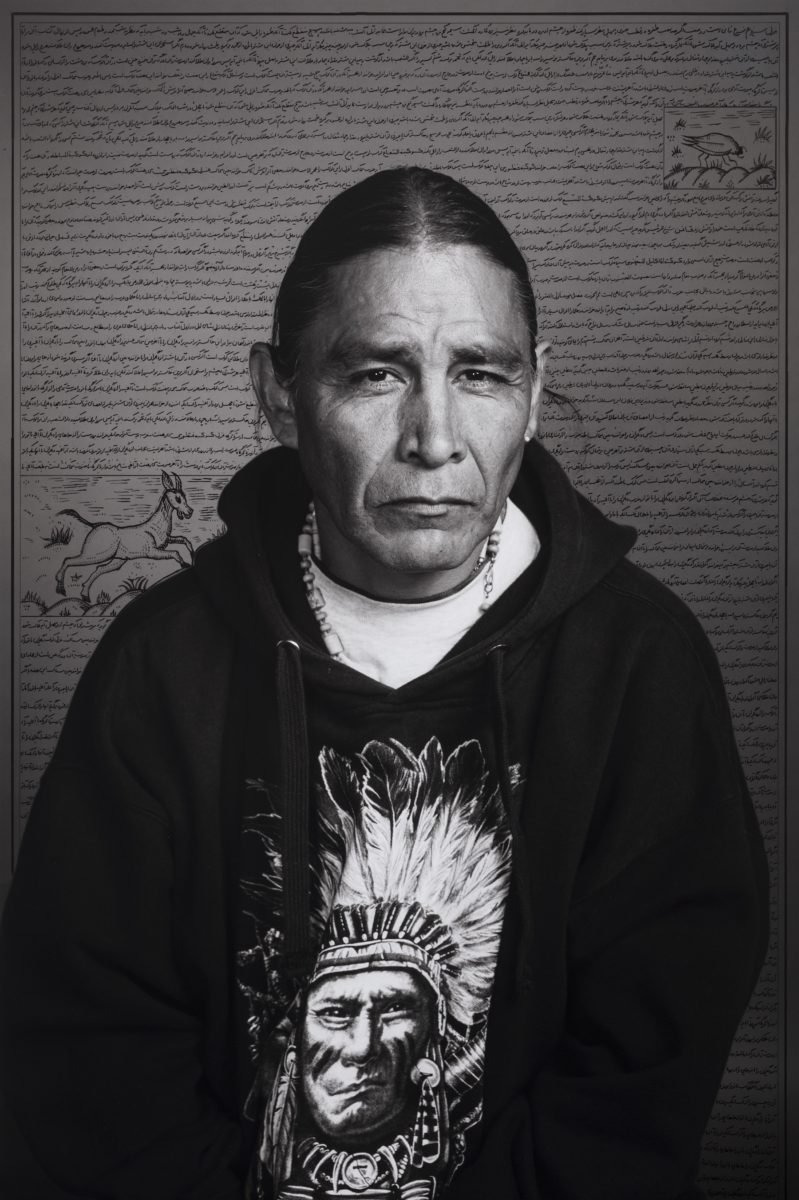

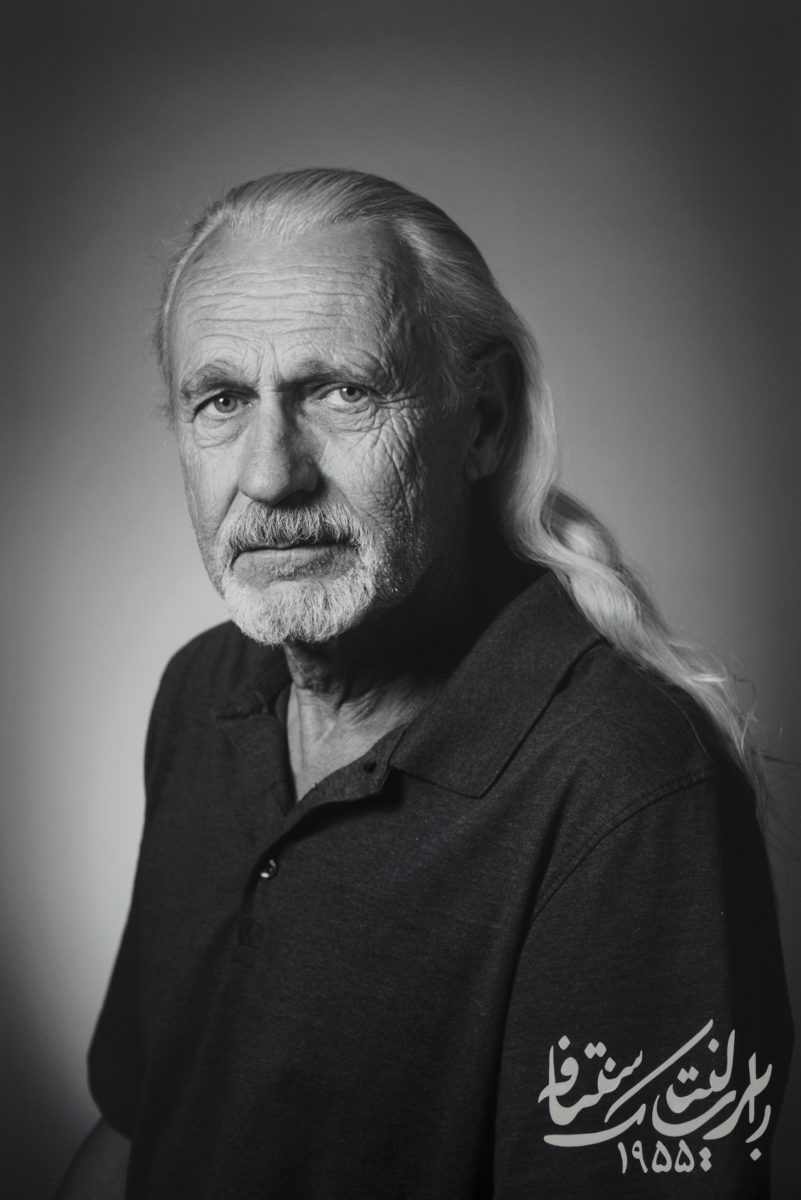

- Left: Robert Lenick. Right: Herbie Nelson. Both from Land of Dreams series, 2019

Shirin Neshat, Land of Dreams, 2019

What happened to the American Dream? In the dystopian settings of Shirin Neshat’s three-part film and photographic work, the exiled artist gives her own version, following a young Iranian woman, who, like Neshat herself, is in search of a place to belong and call her own in a mythologised and fractured land. Land of Dreams itself unfolds like a dream, with surreal sequences and Neshat’s signature black-and-white. Portrait photographs that accompany two film works document the disillusioned and disenfranchised people of the US, the displaced dreamers. The work is a rich depiction of the US through the eyes of an immigrant, and an incisive commentary on the impact on individuals under Trump’s regime.

Gina Beavers, American Flag Sponge Butt Cake, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen. © Gina Beavers. Photo credit: Lance Brewer

Gina Beavers, American Flag Sponge Butt Cake, 2020

In an age often characterised by a collective addiction to the internet, Donald Trump’s uncensored Twitter rampages are surely the toxic beacon for our screen-based entrapment. The source material for the thickly-layered compositions of American artist Gina Beavers is rooted in the digital images that circulate online, from #FoodPorn to make-up tutorials. Her unusual paintings, which border on sculpture, are built up through dense accumulations of acrylic medium or foam. Inspired by underground comics and outsider art, her work explores contemporary trends, highlighting the divide between our digital and physical lives. She raises questions around the desires and self-obsession that have come to define our age. American Flag Sponge Butt Cake satirises the relentless pressure to perform amidst a culture focused on the attention economy, serving up an all-American slice of a posterior in a minuscule striped bikini. Good enough to eat?

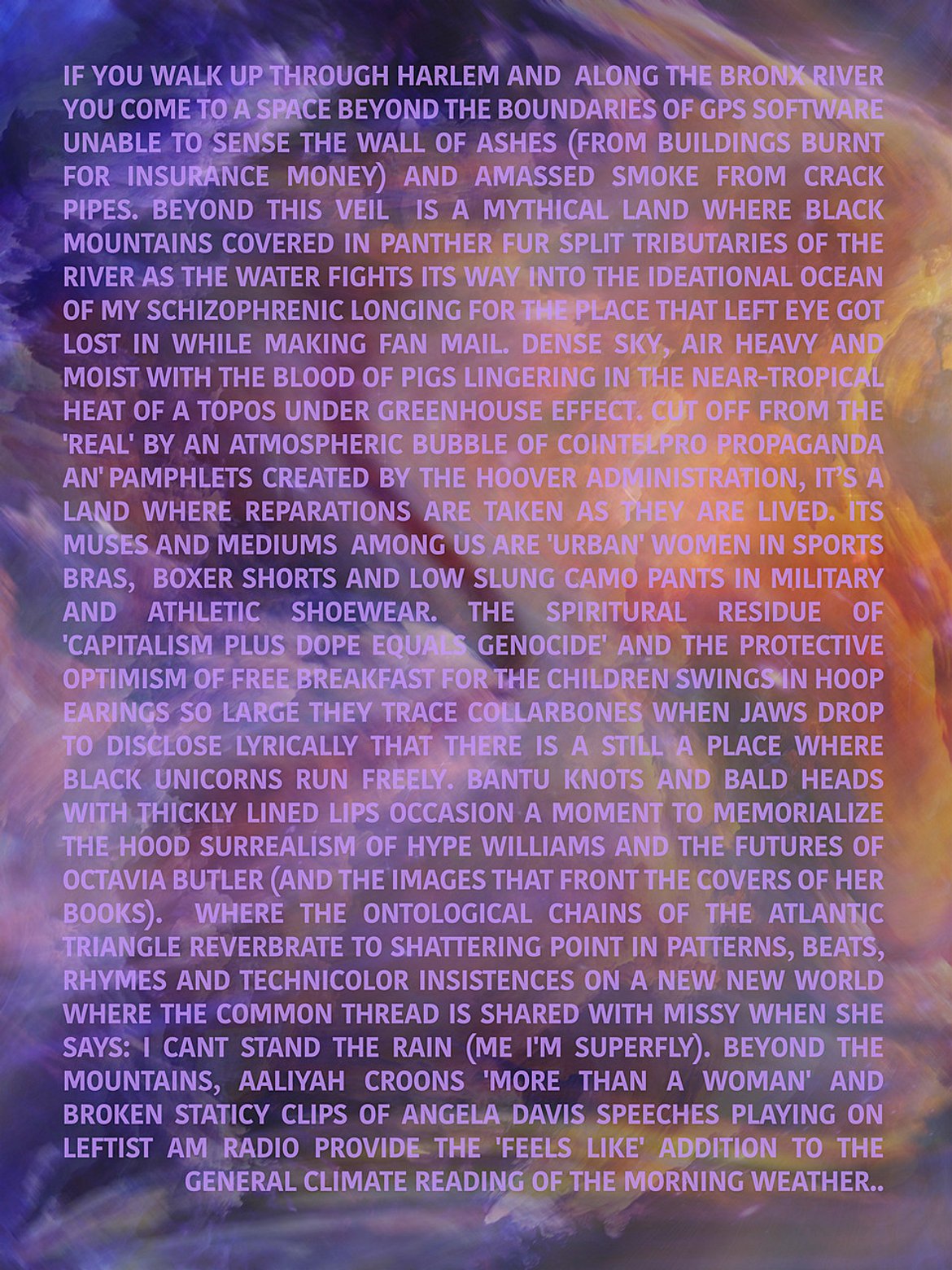

Juliana Huxtable, Untitled (Casual Power), 2015

In 2015 Huxtable was dubbed the star of the New Museum’s Triennale, starring both as artist and muse. One of the works Huxtable herself presented was Untitled, (Casual Power), a prose poem written in caps to emulate the text commonly used on social media. Mixing high and lowbrow cultural references, from Octavia Butler to Lisa Left Eye Lopes, she gives a remarkable, circular and personal account of the contemporary history of black people in the US, bringing the experiences, sights and sounds of several decades vividly to life in the present moment.

- Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Obodo (Country/City/Town/Ancestral Village), 2018-19 Installed at MOCA Grand Avenue (250 South Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90012) from January 9, 2018 - February 25, 2019. Photo: Elon Schoenholz.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Ancestral Village, 2018-19

Akunyili Crosby created this enormous installation for an entire side of MOCA’s building on Grand Avenue in Los Angeles. Akunyili Crosby’s works are composites whose many pieces and fragments create multiple, simultaneous narratives, reflecting the experiences of the many people who live in, or pass through, a multicultural city like Los Angeles. This vinyl mural with images of interiors and individuals in their space riffs on the many meanings of ‘home’: the closer you look, the more the details reveal themselves and tell more stories about the people and places in them. As an LA-resident herself, Akunyili Crosby’s monumental work symbolises the complex tapestry of the city’s community, while paying homage to her own homeland, a fusion of her past and present.

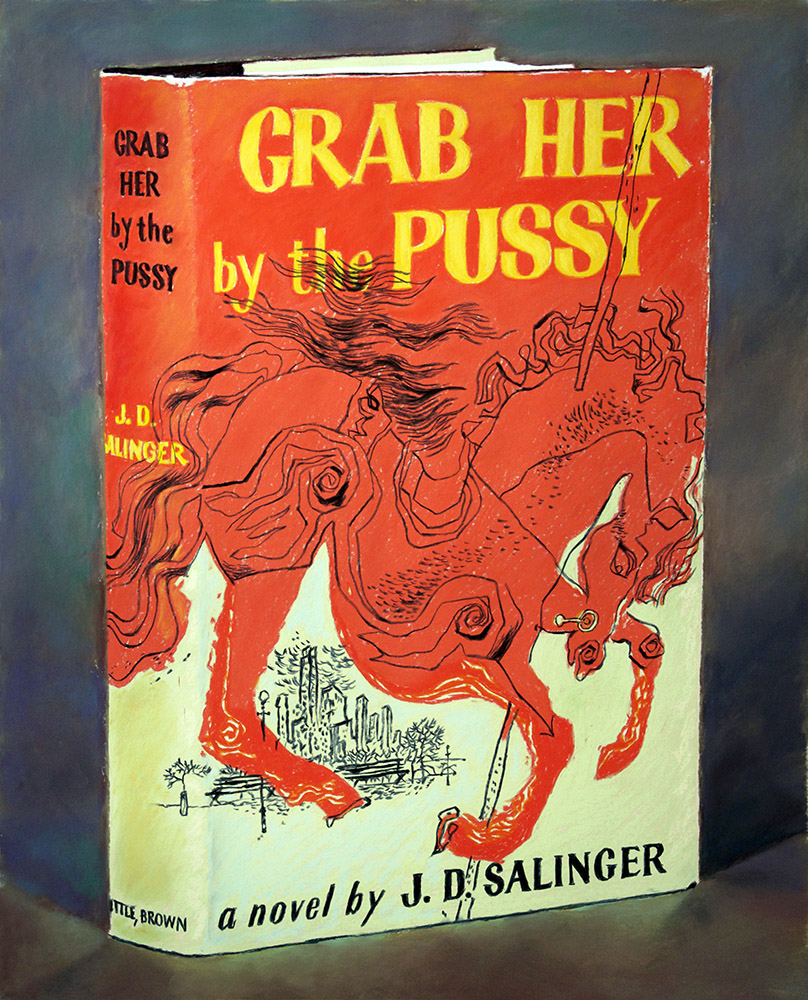

Eric Yahnker, Alternative Fiction, 2017

In his 2017 image, Grab Her by the Pussy, California-born artist Eric Yahnker reworks the recognisable image of J. D. Salinger novel Catcher in the Rye while incorporating Trump’s vile statement “Grab Her by the Pussy” into the book’s cover text. The choice of the coming-of-age novel is interesting: at its most basic, it has been read as a treatise on adolescent anger and rebellion against “phoneys”; it has become infamous for being associated with several high-profile shootings, including John Hinckley Jr.’s assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan and Mark Chapman’s fatal attack on John Lennon. As such, Yahnker’s piece can be seen as a comment both on Trump’s idiotic “locker room” misogyny and the thorny debates around American gun laws. It also references the wider issues around truth and “phoney”-ism: the image is drawn from a series titled Alternative Fiction, a play on “alternative facts”, a phrase used by US Counselor to the President Kellyanne Conway during a press interview in 2017.

- Martine Syms, Notes on Gesture, 2015. HD video. Courtesy of the artist and Bridget Donahue, New York

Martine Syms, Notes on Gesture, 2015

LA-born artist Martine Syms created Notes on Gesture as a riff on the phrase “Everybody wanna be a black woman but nobody wanna be a black woman,” according to the Video Database. The video work sees a black female actor play out gestures that are seen as being stereotypical (and reductive) expressions of Black women. Syms enacts finger snapping and other tropes frequently co-opted as mimicries of no-nonsense, one-dimensional views on the body language and essences of Black womanhood. The hand actions were based on the seventeenth Century text Chirologia: Or the Natural Language of the Hand, with the actor in the piece performing these alongside employing acting techniques such as “blocking” and “cheating”; while text slogans such as “DON’T JUDGE” and “WHEN IT AIN’T ABOUT THE MONEY” are peppered throughout the work to further highlight the dangers of reducing a vast swathe of people to a singular, flat identity.

Nina Chanel Abney, Who’s Got Team Spirit?, 2015

This series draws upon the symbols of American patriotism, which Abney describes as having become synonymous with

White Nationalism. In recontextualising Fourth of July celebrations, the moon landing and even the very idea of displaying the stars and stripes, she considers how and why one feels compelled to patriotism, and questions who is allowed to occupy that role. Furthermore, by including more subtle emblems of commerce, media empires and all-American products, she alludes to the widely caricatured national identity of the United States in the eyes of the wider world.

Zoe Leonard, I Want A Dyke For President (updated recital by Mykki Blanco), 2016

Zoe Leonard’s typewritten poem from 1992 was originally written to celebrate poet Eileen Myles’ campaign for the presidency, but it is still vitally relevant today. In reeling off the qualifications that should make one eligible for high office, she eschews an Ivy League education and lofty resumé in favour of everyday human struggles, whether it be having abortion, being the victim of a hate crime, facing deportation, or simply waiting in line at the DMV. In 2016, performance artist and rapper Mykki Blanco recited the piece in a film directed by Adinah Dancyger, just in time for the fateful election result. Unfortunately, this analysis of the laughably narrow pathway to political power and the experiences of those who wield it is still prescient. One can only hope that one day all of Leonard’s wishes come true.

Paul McCarthy, DADDA, Donald, Green Screen, 2019

Paul McCarthy isn’t one to shy away from controversy. Over his more than 40-year career he has doused himself in ketchup and created lewd sculptures of pigs engaged in sexual intercourse with political figures and Disney characters alike; he was also the artist behind the now infamous “butt plug” Christmas tree installed in Paris in 2014. Based in LA, Hollywood has inevitably infused his working practice, resulting in a series of feature-length films. Set in a dystopian American Western-inspired world, sex, violence and death are pushed to their limit with an exuberant cast of damsels in distress, a John Wayne-influenced cowboy and a character named after Minnie Mouse. Naturally, there is a Donald Trump figure played by McCarthy himself, face covered in make-up and blonde wig askew, shot during the period that Trump took office in 2016. “I think of my work as using a type of exaggerated normality,” he explained in an interview with Elephant in 2019. “They’re caricatures that represent a broader swoop of American culture.”

Words by Louise Benson, Holly Black, Emily Gosling and Charlotte Jansen