Since the birth of our daughter, the enquiry my wife Tess and I most often have to field is “Are you getting any sleep?” Though kindly meant, it feels like a trick question. Of course we’re getting some sleep—just not enough—and when asked about it I sense, with the paranoia of the persistently wakeful, that I risk appearing either querulous or suspiciously stoical.

One thing’s for sure: when you’re not getting your head down a lot, you don’t want to read about the dangers of sleeplessness, so I’ve been making slow progress with Matthew Walker’s book Why We Sleep, which I bought back in pre-parenthood days. Walker’s account is urgent and enlightening. It’s also cautionary to the point of being terrifying: “A lack of sleep… is a deeply penetrating and corrosive force that enfeebles the memory-making apparatus within your brain”, “Getting too little sleep across the adult life span will significantly raise your risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease”, “Chronic sleep loss will erode the very essence of biological life itself: your genetic code and the structures that encapsulate it.” No wonder I keep finding excuses to pick up other books, especially ones with obviously analgesic properties, though even Dante’s Inferno would seem restorative by comparison.

“The idiom ‘to sleep like a baby’ strikes me as not merely hackneyed, but absurdly off-beam”

Missing out on my zeds each night makes me romanticize the past, a sleep-glutted dreamland. It’s as if, pre-baby, I basked the centuries away (the phrase is Emily Dickinson’s)—my soul a hushed casket (that’s Keats), a smooth dark wave slipping over my head (that’s Margaret Atwood). The truth is that, while never exactly a nomad in the wilds of insomnia, I was also never one of those people whose consciousness pleasantly ebbs away the moment they make contact with a plump cool pillow. Yet now I wake each morning believing that I’m a sentry who’s for a moment nodded off on duty; my neck is hot and stiff, my eyes are rusty slits, and it’s as if my brain has dried up, the inside of my head an old bread crust.

An aside: the idiom “to sleep like a baby” strikes me as not merely hackneyed, but absurdly off-beam. I aspire to sleep like a lake, or a bee in its honeyed cell, rather than napping intermittently and stirring every hour or two, emitting hungry shouts.

Recently, in the middle of a disturbed night, I conjured up a list of sleep art, and now, as I hide my face from the white knives of the morning sun, I return to it.

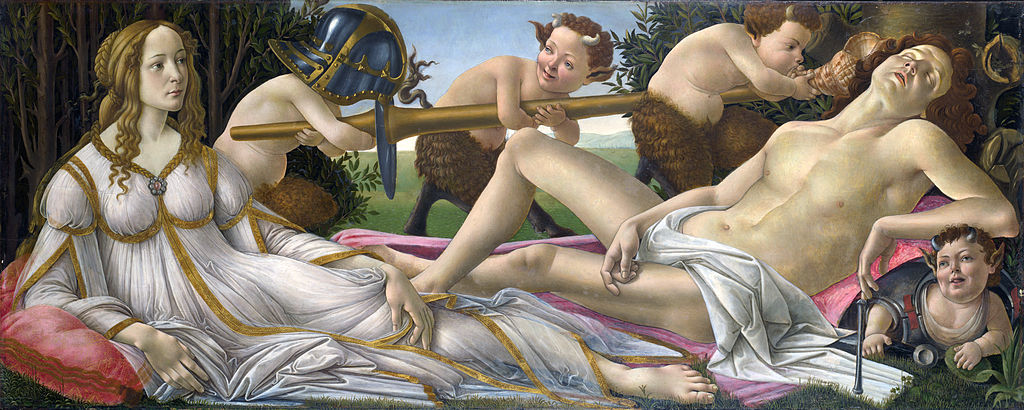

I think of Botticelli’s Venus and Mars, in which Mars, apparently recumbent after sex, won’t wake despite a satyr blowing a conch next to his ear; meanwhile Venus is vigilant, alert, a touch censorious—a look I’ve met in real life. The painting, it’s suggested, was originally the backboard for a day bed, and I pause to envisage such a luxury.

I see Lucian Freud’s canvas of benefits supervisor Sue Tilley—on her side, wedged at one end of a shabby flowered sofa, in what I call the “park bench position”. Then there’s Dalí’s Sleep, with its disembodied and distended fragile yellow head supported by delicate crutches: everything here suggests the imminence of collapse. Other images follow: Toulouse-Lautrec’s Le Lit, Klimt’s The Virgin with its tangled limbs and tangled scarves, Millet’s Noonday Rest (with discarded sickles, bottom-left) and the Van Gogh of dozing workers that it inspired (also with discarded sickles, bottom-right).

Next, I summon up Millais’s L’Enfant du Regiment, in which, amid the turmoil of the French Revolution, a girl who’s been wounded by a stray bullet rests innocently on a tomb, covered by a soldier’s tunic, in tribute to sleep’s healing potential. I recall Andy Warhol’s film of his out-for-the-count lover John Giorno—an extended essay on the death-haunted hours before dawn, its 320-minute running time ironic, given its creator’s legendarily meagre powers of attention. My mind is now racing, crowded with sculptures by artists as different as Brancusi and Canova. I think of Antony Gormley’s “inhabitable” hermit’s cave at London’s Beaumont Hotel, and of all the snoozing Roman Cupids, including the one by Michelangelo that made his reputation and is sadly lost.

But what about images of sleeplessness? I compile an anthology of examples—a perfectly masochistic way to occupy the small hours. Here’s James Thomson’s poem from the 1870s, The City of Dreadful Night: “The city is of night, but not of sleep… The pitiless hours like years and ages creep.” Here are the rhythmic after-dark doodlings of Louise Bourgeois—“a kind of rocking or stroking, and an attempt at finding a kind of peace.” Here’s the young woman in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s story The Yellow Wallpaper, fascinated and tormented by the mutating patterns of the decor in her bedroom. Here are Dr Seuss’s Midnight Paintings, furtively created in his studio and only exhibited after his death, and here are the ugly, ominous crows in Damien Hirst’s Insomnia, a triptych produced as an homage to Francis Bacon.

Yet for me, art’s patron saint of sleeplessness is Edward Hopper. The first of his paintings to come to mind in this context is, unsurprisingly, his most famous one: Nighthawks, that much-parodied vision of lonely people killing time in an apparently doorless New York diner, resembling specimens in an aquarium.

I think, too, of Hopper’s earlier Hotel Room and Eleven AM, both of which suggest not just boredom, but a stultifying dullness, the captivity of an unventilated room, the anchoring effect of fatigue. When he portrays people who are actually sleeping, as in Summer in the City and Excursion into Philosophy, Hopper also includes their wakeful, pensive companions. Even when he shows us a couple who may be about to go out for the evening (Room in New York) there’s the sense that each of them is isolated and might just as soon flump down for an hour. These are vignettes of melancholy and exhaustion, of those conditions’ power to make their victims anonymous, and of night as a place of anxiety.

Images of sleepless parents aren’t so easy to call to mind. Racking my brain, I come up with Caravaggio’s Rest on the Flight into Egypt

: Mary and Jesus are locked together in that semi-sleep I associate with families held up at the airport, an awkward huddle that follows a lot of overwrought manoeuvring and makes me think of compromise, not repose.

“Artists have tended to associate sleep deprivation with nocturnal entertainment or the vagaries of the feverish creative mind”

Trying to add to this list as I wrestle with a pillow that’s as flat as a shadow, I instead draw up a mental catalogue of artistic representations of beds, and spell out all their uses besides sleep: giving birth, retreating from the bustle of the world, reclining nude for the delectation of the artist and his or her audience, reclining nude for one’s own delectation, writing or composing, conversing intimately, having sex, celebrating the indolence of majesty, worrying, praying, daydreaming, languishing in sickness and dying—shabbily, perhaps, and in many cases obscurely, yet sometimes passionately, madly, tragically. As this inventory darkens, I’m struck, too, by how often artists equate bed not with bliss, but with fear.

More than that, though, I’m struck by how few images I can remember—or find—that do justice to the relationship between sleeplessness and parental (particularly maternal) responsibility. Artists have tended to associate sleep deprivation with nocturnal entertainment or the vagaries of the feverish creative mind, not with the toil (a noble toil, but toil all the same) of sustaining another person’s life, providing nourishment and comfort and the conditions for that tiny individual to get as much sleep as possible.

There are hints of this toil in some of the works I’ve identified, by Hopper or Caravaggio for instance, but they’re not much more than hints. Artists have mostly chosen not to document mothers’ vigilant travails, perhaps because they have failed to notice them, or perhaps because they’ve supposed that it’s more salutary to idealize motherhood. This seems a failure of empathy, and it’s worth noting, too, the broad tendency to represent those who are awake when most people are asleep as outsiders, even as morally dubious, rather than to recognize that many of them are society’s backbone, the wrung-out yet resolute custodians of its very future.