Torbjørn Rødland is excited about teeth—the focus of his upcoming Manifesta 11 project and a feature of his summer solo exhibition at Zurich’s Galerie Eva Presenhuber

. “Teeth are part of the vocabulary of the subconscious,” he tells me when we Skype, between LA and London, late one night. “I saw a picture in a tabloid magazine of a woman posing with her dentals. I think that was the trigger. This was years ago, so when I was invited to choose a profession, someone to collaborate with for Manifesta, I chose a dental technician or dentist. She gave me access to teeth, both natural and artificial. I got to visit the lab that produces her dentals and I got to photograph her working on a couple of clients.”

Of course, the dental industry fits perfectly with the artist’s practice which similarly teeters along the line separating care and cruelty—a variable line, depending on quite how thorough your hygienist might be. “I’m interested in these human connections,” he tells me, “when it’s unclear if the hands reaching out are horny, healing or hurting. For a few years in Oslo I went to a dentist who I think had sadistic traits. Just a cleaning hurt more than it had any reason to.”

It is this ambiguity between horny, hurting and healing that first hits with Rødland’s photographs. An ambiguity that feels intriguingly perverse, despite the carefully limited inclusion of graphic content. The photographer understands the subtleties of the human body—and indeed all the potential excitement that those subtleties bring with them. A young woman’s finger, arched and dangling suggestively in a sunlit beer in Golden Lager (2007) takes the mind to uneasy places; the big, tanned hands of a grown man that reach towards a girl’s mouth in This Is My Body (2013–15) certainly border on the disturbing. Or do they? Perhaps he’s just pulling a tooth.

“Art as photography is always in dialogue with photography as advertising”

The subjects of his pictures generally dwell in a state of inequality with one another, most often finding themselves in this imbalance due to their youth. Typically, the second subject exists off-camera, sometimes as a pair of hands, at other times as Rødland himself. “Art as photography is always in dialogue with photography as advertising,” he explains. “When I try to show two similar people in harmony in a photograph it quickly reads as either a commercial picture or as an ironic response to a commercial form. On the other hand, I have a clear need to see opposite forces in union. It’s how the world presents itself to me.”

Innocence, it seems, is always on the verge of being smashed to smithereens. But these power relationships do sometimes find themselves in reverse in his photographs, the innocent—recognizable for their clean white socks, tennis sneakers and decidedly Nordic complexions—pushing back. Summer Scene (2014) sees a victorious, scuffed plimsoll-clad foot (white sock and all) crushing the face of a bespectacled man. The mind wanders to the worst possible back-story and one feels a sense of satisfaction at this unleashed wrath. But beside these obvious turnings of the tables, there is also a sense in a majority of his images—a look in the eyes—that the younger characters are privy to a world that belies their apparent purity. This world is not as black and white as it might first seem; it is complicated by the presence of knowing innocents.

Innocence is tricky terrain, and it has been previously noted—not always favourably— that female innocence is a running theme in his work. I wonder what draws him to this material. “Eroticism is a needed addition to cerebral conceptual art, and innocence is a powerful state. What can I say? In the postmodern, innocence is a construct. Every experience is a blessing. It’s complex. You’ll also find virgin boys and animals in my pictures, though, and my childhood and youth is probably the real background.”

“There’s a richer cultural history and discourse behind intuitive, inexperienced young girls,” he tells me, and it is quite obviously a topic that he has considered—most likely defended—many times before. “It’s so politicized, and I realize of course that it’s not my job to take part in the discussion. We want women in these driving seats. As a straight, white male I better focus on other issues than minority rights. When I started it was extremely complicated. I was my own model for the first four years. I never thought I would photograph a naked female body.” But, he claims, “I’m standing on the shoulders of feminist art. Sometimes it tries to shake me off, but in retrospect it will all make sense.”

While Rødland’s work displays the warping of innocence, much of it also feels like an ode to this state and, as he mentions, his own childhood forms a part of the bigger picture. “What has slowly crept up on me is a willingness to admit the personal aspects,” he tells me when I ask how conscious this influence has been over the years. “The previous generation of artists typically won’t go there at all. Maybe because a personal reading has a wider appeal and therefore tends to dominate or take focus away from other, more abstract or critical readings of the work. So yes, the link from my early photography to my teenage years is pretty clear. But unlike these New York hipster projects which grow from having a really cool and active group of friends, my early work deals with the experience of being utterly alone and seeking the comfort of the forest so as not to be seen as a loner lacking social skills.

“I look for a depth beneath the randomness of image production in our current pluralistic culture”

“This is the beautiful twist: making something to feel better about hiding in the woods evolved—after I started involving other people in my photographs—into a life. The symptom turned into a cure. It’s my space but I depend on the input of strangers and friends to make it fully come alive.”

Although many of his images are set indoors, in manmade surroundings, nature is a key player. Scenes are sun-spattered, his subjects have flushed pink skin, hair is natural, and animals play a large part (if rather often making appearances as meat or fluffed-up pets). It’s as though the pure, natural world is constantly finding itself warped by the world of man. In fact, in 2008 he published a book of photographs, I Want to Live Innocent, in which he returned to Stavanger to explore the rapid development of this city which plays a big role in Norway’s oil industry; dominated by gas pumps, flattened land and piles of bricks, promising ongoing redevelopment. I wonder if Rødland feels this contradiction, living and working in LA, a built-up city, that is surrounded rather arrestingly by nature.

“Yes!” he confirms. “It’s how we roll: humans! The underlying ambition is to unite and to be at peace with these so-called contradictions. I live in the hills, there are birds singing outside my open door now. The deer and coyotes come out at night. Yet I can walk to gyms, restaurants and cinemas from here.” I wonder if LA has had a direct impact on the practice of this boy from the Norwegian woods. “Probably not,” he reckons. “It’s hard to see from the inside. The motivation is interior, but I constantly reach out to include things, people and places, and then Los Angeles is right there. I need exterior support to create a photographic picture and in many ways this is what LA is about: reality supporting and slipping into myth.”

Certainly from the outside there appears to be the occasional exploration of the fanciful LA life. A great example of this is the 2014 Hilton series that the photographer created for Purple Fashion—featuring Paris Hilton dolled up in pink and peach, blonde hair flowing, powder puff-style pooch under her arm—in which Hilton encompasses every aspect of the Rødland muse: “girlie”, sugary, prim but, beneath the surface, suggestively dirty. Similarly The Curve (2012—15) shows a white limo rounding a recognizably Hollywood hill, nothing at all out of the ordinary, but suggestive of all manner of darkness afoot—perhaps already in action behind the blacked-out windows. As with all of his images, one simple scene leads to a multilayered response.

Picket Fence, 2015. Courtesy of Galerie Eva Presenhuber

This layered image making is an element of the artist’s photographs that has been discussed many times as going against the grain of the throwaway, rapid image production that dominates photography today—albeit of a mostly non-professional nature. Surprisingly, Rødland doesn’t think that style of image making is such a bad thing. “I look for a depth beneath the randomness of image production in our current pluralistic culture,” he tells me. “When a medium, a motif or tradition is emptied out, the only sensible thing to do is to try to slowly fill it with something. Too much contemporary art continues to criticize content or induce fragmentation. That just feels old to me. You don’t dance on the graves if all your friends are dead, but you cannot reject fragmentation either. You cannot put Humpty Dumpty back together again. That would be nostalgia—a longing for less complexity. I’m all for more complexity!”

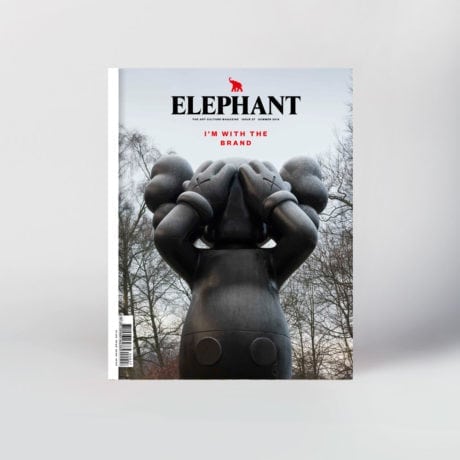

This feature originally appeared in issue 27

BUY ISSUE 27