The Brixton studio of Zineb Sedira is in a state of flux. As the artist prepares for her first solo exhibition in a UK gallery for more than 12 years, Can’t You See the Sea Changing? at the De La Warr Pavilion, part of her working space has been transplanted to the Bexhill-on-Sea gallery for visitors to enjoy.

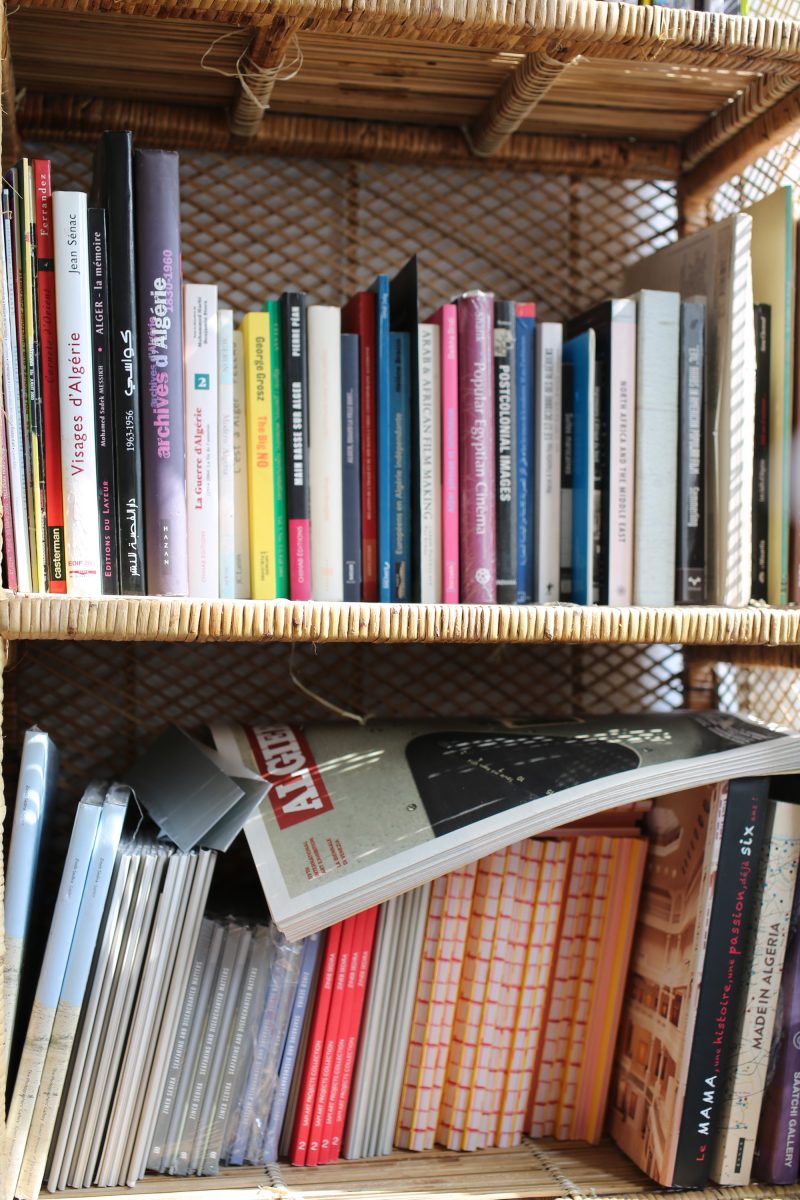

“We agreed that in order to combine something closer to what I did at the Venice Biennale and my older work about the sea, we would take part of my studio there,” Sedira explains. “I have so much vintage stuff related to the sea that I’ve collected over many years, so I said why not recreate a little display of two shelves from my studio.” She’s also planning to leave her studio soon and return to working from home. As such, the room is filled with boxes and past work piled up on the remaining storage units, awaiting their new residence.

Movement, journeys, and the transplanting of spaces have long been key facets of Sedira’s work. Primarily a filmmaker, but also working with photography, installation, and collage, the Franco-Algerian artist has explored the history of her parents’ migration from Algeria to France, its subsequent impact on her family dynamics, and, most extensively, the sea as a symbol of passage. In her own words she is “a guardian of memory”, concerned with “looking at forgotten stories and bringing them to the forefront”.

“Algerian history will be totally different to French history about Algeria. Who tells the truth, what is the truth?”

She has developed these ideas further with her film work. 2019’s mise-en-scène grew out of two “rusty, beautiful” film canisters she found in an Algiers vintage shop, their contents too damaged to restore properly, but there was enough there for her to piece them into her own work. The colours of the film’s decay bleed across the hazy images to create a kaleidoscopic work peppered with glimpses of a lost past. She’s framed certain stills on her studio walls, along with images of the canisters themselves, which she loves. She mourns the loss of metal in favour of plastic to store film now, despite its greater protective properties.

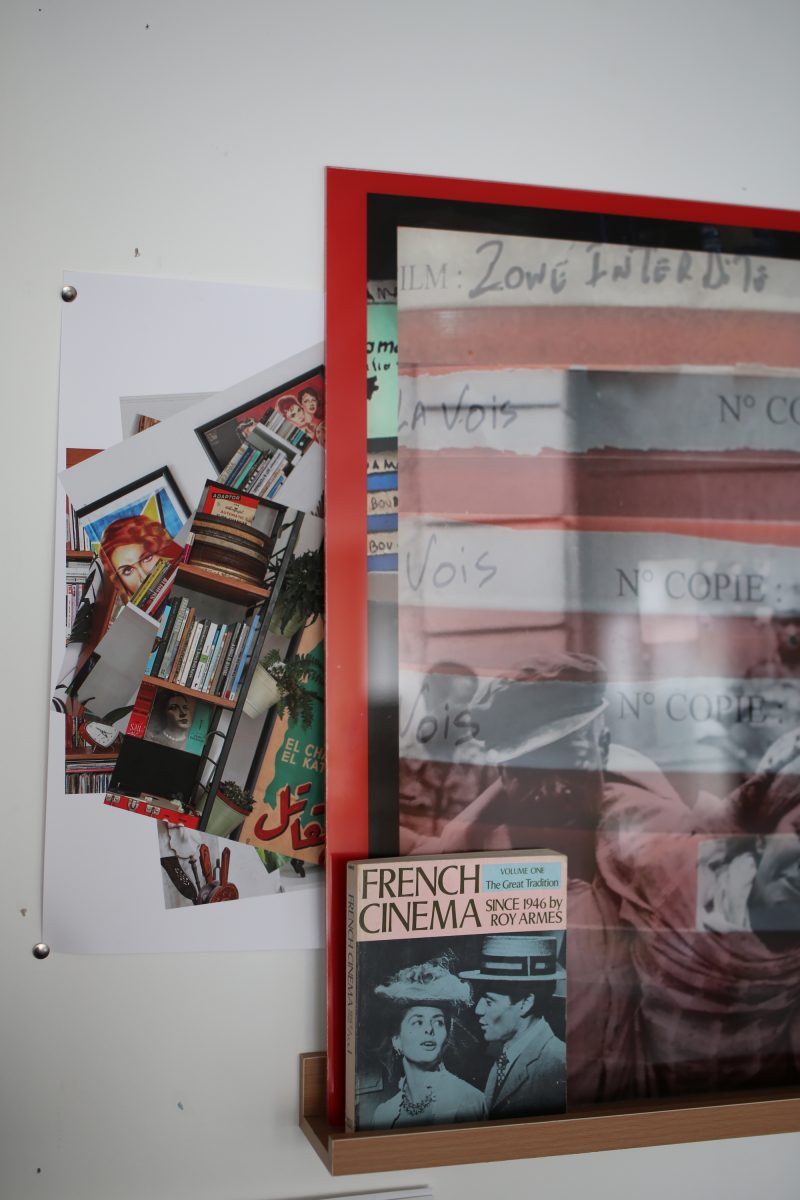

These forgotten stories interplay with Sedira’s interest in how history has been recorded. “We have so many different angles,” she explains. ”Algerian history will be totally different to French history about Algeria. Who tells the truth, what is the truth? Can you trust the archives that compiled and saved certain records?” After another recent archive dig, she found a copy of a film by Italian director Ennio Lorenzini shot in Algeria two years after the country achieved independence from France in 1962. Lorenzini’s Les Mains Libres (1964) was restored with the help of the Cineteca di Bologna and presented earlier this year at the famed repertory cinema festival, Il Cinema Ritrovato.

Sedira has worked in the same Brixton building for around six years, but it’s her home, a five-minute walk away, that offers the best artistic environment. “A lot of my work is autobiographical and I like working from home because I’m informed by my surroundings,” she says. “My living room is very cosy because I’ve got a lot of 1960s objects everywhere and paintings and furniture. I buy a lot from flea markets and car boot sales.” This very living room became a 2019 installation at the Jeu de Paume in Paris, where Sedira copied over every detail to the gallery space and recreated it piece by piece.

Accordingly, the decision to leave her current studio has not been overly difficult. “My practice is not studio-based really,” Sedira says, “I’m more of a filmmaker and photographer, I go on site and film. So I don’t use the studio in the same way as other artists and a lot of the time I’m hardly here.”

“My practice is not studio-based really. I’m more of a filmmaker and photographer, I go on site and film”

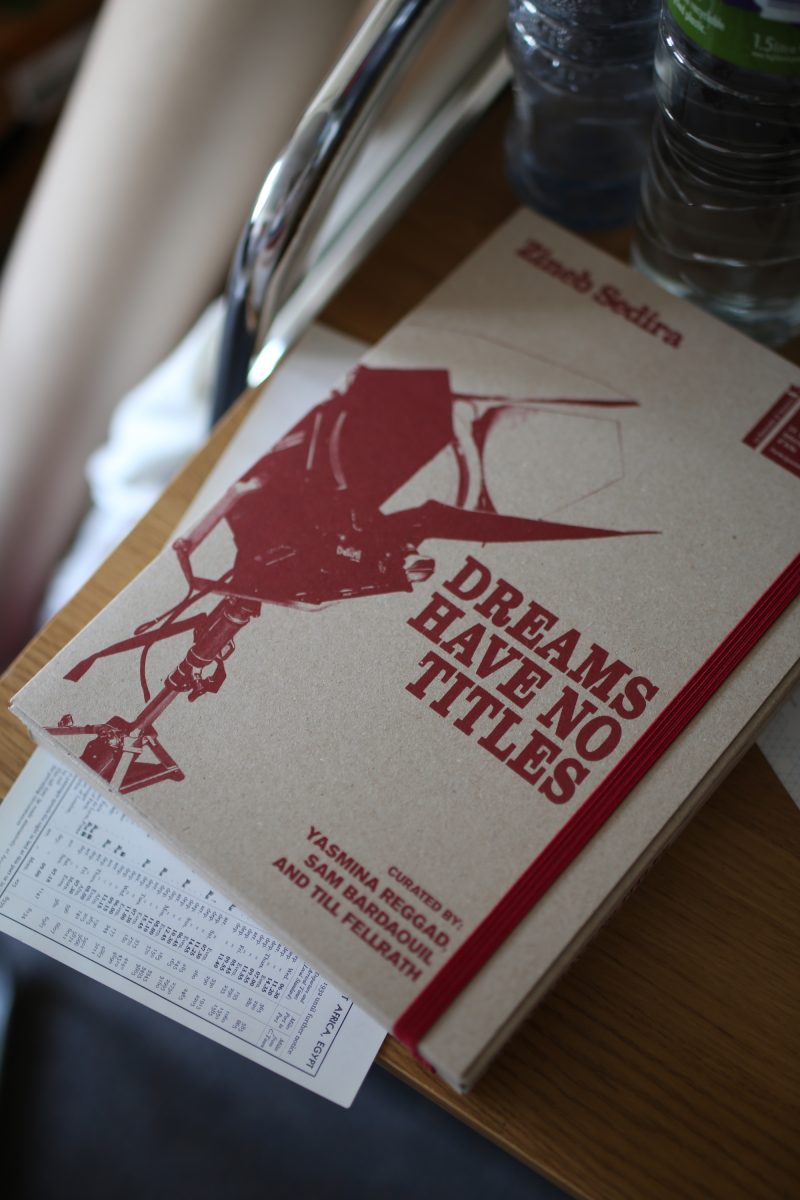

She explains that her need for a studio now is predicated on the growing commercial interest in her work. “This is changing my practice, especially after Venice, because there is more demand for buying work,” she says. “I’m quite glad about it because it’s nice to be more hands-on. I’ve spent two days doing some collages with my assistant and it was a lot of fun. I realised how much I missed actually being there and cutting stuff up and getting messy.” These collage works cover a table in the centre of the room, a patchwork of images taken from the French Pavilion at Venice where Sedira presented Dreams Have No Titles.

There’s not a vibrant collective spirit among the other studio residents in the building, she explains, but the Brixton community she’s lived in for around 30 years has had a lasting impact on her. It followed her all the way to the Biennale, where she revisited her living room installation, and in which Sonia Boyce (Britain’s Golden Lion-winning representative and Sedira’s old friend and neighbour) took part, through a pre-recorded film.

“I’ve realised how much I missed actually being there and cutting stuff up and getting messy”

Dreams consisted of further room recreations as Sedira re-staged scenes from famous works of militant, anti-colonial cinema such as Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966) to explore the relationship between history and fiction, reality and what is presented as truth. In overlapping film scenes with her own artistic expression (a dance performance, inserting her family into the installation, the use of mise-en-abyme with images and film clips playing within the space), Sedira introduces layers upon layers of references and meaning to build a sense of what she calls “fiction-reality.”

The show at the De La Warr Pavilion comes at an exciting moment for the artist’s practice. She acknowledges her focus on the sea as a subject ended many years ago but there is something revelatory in revisiting, or recycling, her older work for the exhibition. It is also fundamentally connected to her personal love for vintage clothes and ephemera from the time when she was born. The political climate of decolonisation, anti-imperialism, feminism, and civil rights that typified the 1960s has had clear influence on her work.

“Why am I going to travel to Algeria again to take photos of whatever, when there is so much in my archives?”

“I’m really interested in the idea of recycling by buying existing objects or secondhand clothes, especially in the day to day when we talk so much about having to save the planet. In recycling my work, I’m trying to do the same thing,” she says. “Why am I going to travel to Algeria again to take photos of whatever, when there is so much in my archives? There’s always an abundance of photographs that I don’t use from my film shoots.”

Sedira reflects on the importance of the Venice Biennale on her career, what she describes as “the highest achievement” for an artist, but worries about what comes next. “The problem now is where do you go from there? When you’ve done such a big project, and you’ve gone almost as far as you could, not conceptually but in your career, how do you make the next piece?” she asks.

Who’s to say, but the show at the De La Warr offers a pertinent opportunity for introspection, for taking stock of what has been and what will come. As the Brixton studio is packed up, long-loved items will be moved to a new home where they can be repurposed and reimagined in a new space. It is an opportunity for Sedira’s practice to unfold within itself, to bring the past through to a new future.

Cailtin Quinlan is a film critic and writer based in London

All photographs by Louise Benson

Zineb Sedira: Can’t You See The Sea Changing? Is at De La Warr Pavilion, from 24 September 2022 to 8 January 2023