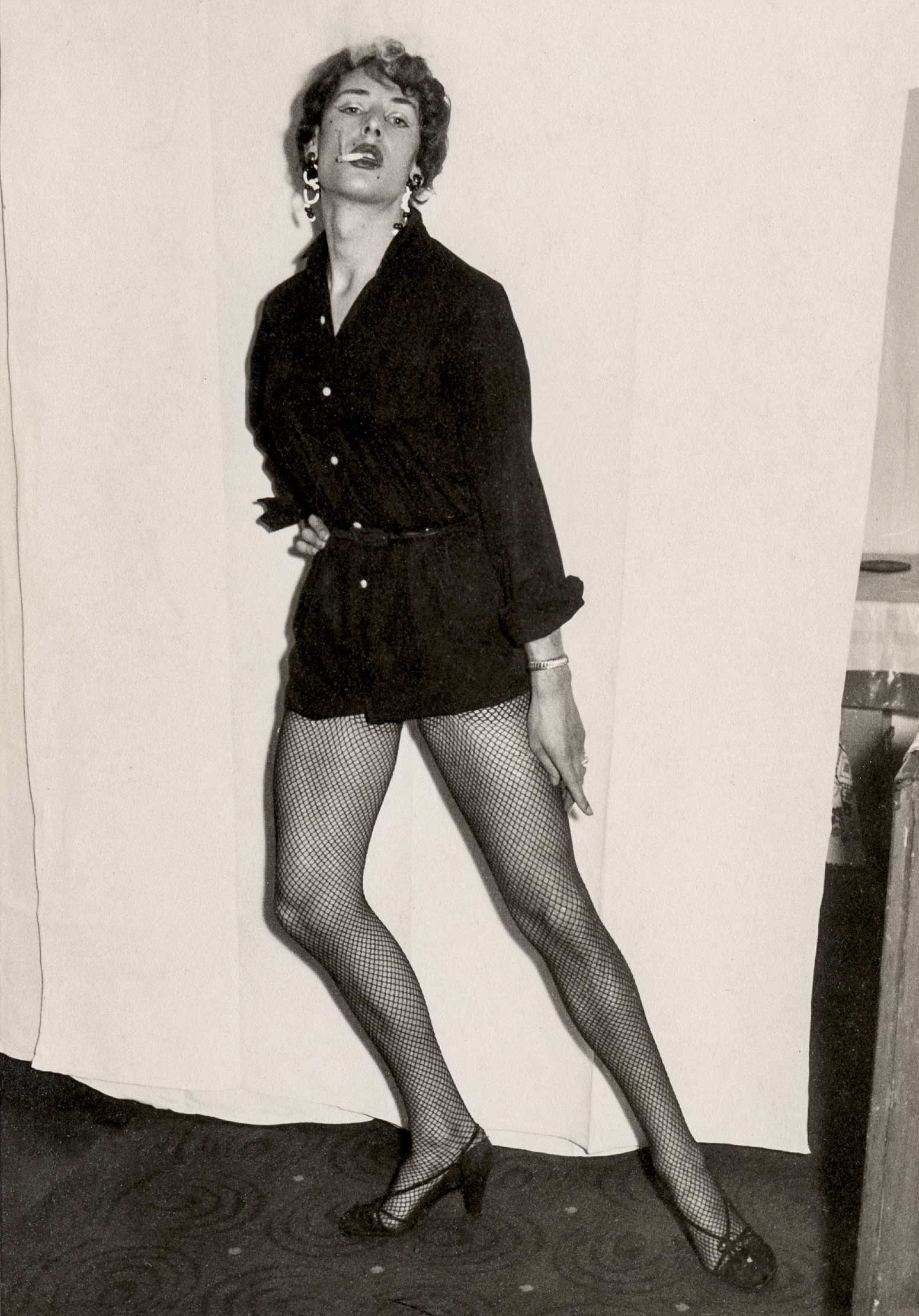

![Guilda, [one of a triptych]. New York, United States, circa 1950. © Sebastian Lifshitz Collection](https://elephant.art/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/03_Press-Images-l-Under-Cover-l-Guilda-1950.jpg)

© Sebastian Lifshitz Collection

“When I started buying found photographs, I didn’t intend to have a collection,” he says. “I was a student and I was in love with the past. I used to go to flea markets in Paris and at that time it was very easy to find photographs that nobody cared about; lost boxes that cost nothing. I just wanted to go home with them and they became my little treasures.” Soon, he began to identify a particular subset of forgotten, clandestine depictions that showed alternate histories of mainstream existence.

“From time to time I found images of cross-dressers and, as a gay teenager, I was very curious because this type of picture was something of a surprise and impossible to find in the press at that time. Today in the media queer culture is big. There is high visibility, but people need to know that it’s not something new. This exhibition is about making these people from the past visible.”

Lifshitz is also quick to point out that this show is not simply a binary tale of men dressing as women. It explores trans identity, feminist militancy, right-wing propaganda, the Parisian cabaret scene and secretive, domestic images of individuals who struggled to present their true selves in everyday life. These interweaving narratives are defined by three overarching themes: men dressing in women’s clothes, women dressing in men’s clothes and the life of Bambi (also known as Marie-Pierre Pruvot), who is considered to be France’s most famous trans woman. She carved out a career as a cabaret performer before retiring to become a schoolteacher in the suburbs.

“The realm of theatre has always been a relatively safe space for gender play.”

Unlike the multitude of anonymous stories that form the bulk of this exhibition, Bambi’s entire life story is presented in an array of childhood images, glamorous shots from the Swinging Sixties and a few more from her alternate later life as an educator. Lifshitz forged a friendship with her while creating his 2013 documentary about her life. “She was quite famous in the cabaret scene,” he explains. “Then at thirty, she said ‘Ok this can’t be my life forever. If I stay, it’s going to be really difficult for me.’ She became a teacher in Cherbourg and her pupils fell in love with her. They couldn’t believe that she came from Paris. She said that the way she chose to make herself seem discreet and unrecognizable was to put a headband on, which I thought was fantastic.” For me, both accounts seem laughably unfeasible. Bambi appears distinctly glamorous in class, and her ineffectual headband gives her the air of an extremely stylish hippie.

© Sebastian Lifshitz Collection

Other equally glamorous images show life as performed by other Parisian entertainers, along with the members of the ballroom scene. These are probably the environments best known to mainstream audiences, yet they are but one facet. Lifshitz points out one of the more unusual cross-dressing scenarios, where inmates at internment camps during World War Two partook in theatre as a way of coping with their awful conditions. Naturally, drag

was required for the female roles, and the costuming is surprisingly elaborate considering the circumstances. The realm of theatre has always been a relatively safe space for gender play, although any liberal viewpoint can be quashed, as this outlet was only provided due to the complete prohibition of women on stage throughout various points in history. That being said, it is still an important facet of the story, with some, such as Kabuki theatre, still prevailing today.

© Sebastian Lifshitz Collection

Other forms of conservative-minded cross-dressing are presented in a fantastic display of early twentieth-century parody postcards demonstrating an anti-feminist backlash. They depict women in an array of hybrid male/female uniforms (it is worth noting that corsets are still firmly in place) and poke fun at the “masculinization” of women who were fighting for the right to vote and broader forms of female equality. Therefore, they were apparently seeking to imitate the “stronger sex”.

“There is humour there, they could dress like a banana or an elephant, but they choose to dress as men.”

Historically, the idea of women’s agency and sexuality has been somewhat overlooked or trivialized, as was the case with Britain’s former homosexuality laws, which ignored female relations altogether. Therefore it is wonderful to see that Lifshitz has uncovered plenty of examples to the contrary. A collection of intimate mock wedding photos taken in American colleges in the nineteenth century show the trend for women embodying the roles of bride and groom, and another group of college snaps show students in full top hat and tails at various social functions, jostling and laughing together. Lifshitz speculates that the latter pastime was specifically linked to the campaign for voting rights, which would account for diminishing evidence directly following the nineteenth amendment. “There is humour there, they could dress like a banana or an elephant, but they choose to dress as men. So it means something, it is militant.”

© Sebastian Lifshitz Collection

Whether politically engaged, sexually motivated or embodying gender identity, all of these images create a colourful tableau of individuals operating in what has traditionally been considered an underground society. Some seem isolated and covert, while others paint a picture of supportive communities and glamorous fantasy, but the true significance lies in merely making these unknown faces visible. At a time when trans rights, gender fluidity and sexual politics are becoming ever more prominent in mainstream discussions, it is important to remember that these present-day concerns are rooted in a long and complex legacy. Lifshitz puts it succinctly: “This type of person has always existed.”

All images courtesy Sébastien Lifshitz and The Photographers’ Gallery

Under Cover: A Secret History Of Cross–Dressers

Until 3 June 2018 at The Photographers’ Gallery

VISIT WEBSITE