Library music is a distinctly peculiar category; it doesn’t slot neatly under artist name or title and its tracks tend to be anonymous and ordered by mood or “production genre”. It might be simply defined—in his book Unusual Sounds, author and filmmaker David Hollander introduces library music as: “incidental film music ready-made for film, television and radio production and used instead of, or in addition to, an original musical score”—but it’s also densely layered. Something about these “incidental sounds” sticks around and seeps into your consciousness.

“To my childhood ears, it sounded kitschy and out-of-time”

When I was a kid growing up around 1980s Britain, library music wasn’t something you could buy in a regular record shop, yet it was the ubiquitous soundtrack for prime-time pop culture. As Hollander explains, its “golden age” was actually the sixties and seventies, when the boom in commercial TV and genre filmmaking called for affordable (royalty-free), accessible musical themes. To my childhood ears, it sounded kitschy and out-of-time; when library music wasn’t setting the tone for sitcoms, adventures and game shows, it was played to accompany the surreal static screen of the BBC test card or daytime Pages from Ceefax (this was the dusty era before 24-7 programming, but it still demanded a jolly melody).

- From Unusual Sounds, published by Anthology Editions

As an adult, I’ve experienced the resurgence of library music through crate-digging DJ culture and specialist compilation albums; I’ve even danced to its cue tunes at retro club nights (memorably, the jaunty funk of the theme to eighties school drama Grange Hill—actually a 1975 library track called Chicken Man, recorded in Munich by prolific British composer/musician Alan Hawkshaw). In Unusual Sounds, Hollander vividly evokes the nostalgia-trippy quality of library music, through detailed profiles of leading production houses, notes about seminal themes and a captivating array of associated visuals: psychedelic, luridly-hued vinyl artwork and cinema posters.

“Romero relates his childhood infatuation with movie scores, but also the creative possibilities that library music presented to him as a debut filmmaker”

This is traditionally the lair of the music or movie trainspotter, though it’s also powered by an infectious passion, which opens up the “hidden history” within Unusual Sounds for broader audiences. The book’s foreword comes from library music’s most legendary enthusiast: US horror icon George A Romero (written a year before his death in 2017). Romero relates his childhood infatuation with movie scores, but also the creative possibilities that library music presented to him as a debut filmmaker, with 1968’s Night of the Living Dead. Having independently shot the zombie horror, Romero teamed up with Karl Hardman’s audio production company to complete its experience, and describes discovering the vast archives:

“Karl’s company had hundreds… (it seemed like thousands)… of records, vinyl discs that contained countless hours of music. None of it was specific to any film, but there were passages entitled ‘Anticipation’, ‘Suspense’, ‘Sudden Shock’.”

The composers of all this music had seen the needs of low-budget filmmakers and had provided scores that could be bought for a fraction of what it might cost to hire a composer and/or an orchestra.

When Romero later created Dawn of the Dead (1978), he actually eschewed the original soundtrack created by cult Italian band Goblin, in favour of ready-made library music in pivotal scenes. Romero’s use of library track The Gonk, by Brit musician Herbert Chappell, over this film’s end credits creates an unforgettable, off-kilter and much-mimicked end-note: a clownish, brassy tune looped against scenes of lurching, moaning zombie masses.

Hollander points out that, as music libraries were freed from the constraints of making hit records, its multi-faceted composers could often afford to be experimental, spanning emerging electronic sounds to folk and jazz inflections. At the same time, he’s realistic about the challenges of trawling through library music archives, where sheer volume isn’t necessarily matched by quality, and stand-out compositions weren’t always synchronized for use onscreen.

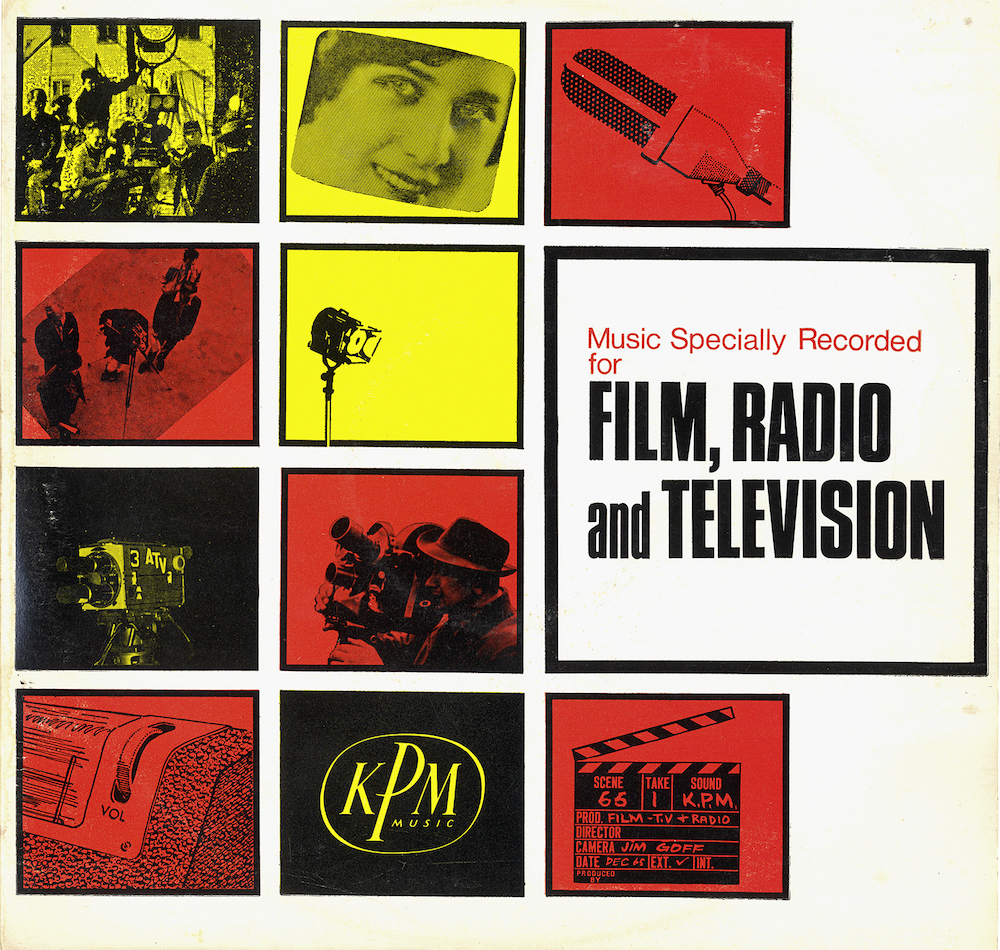

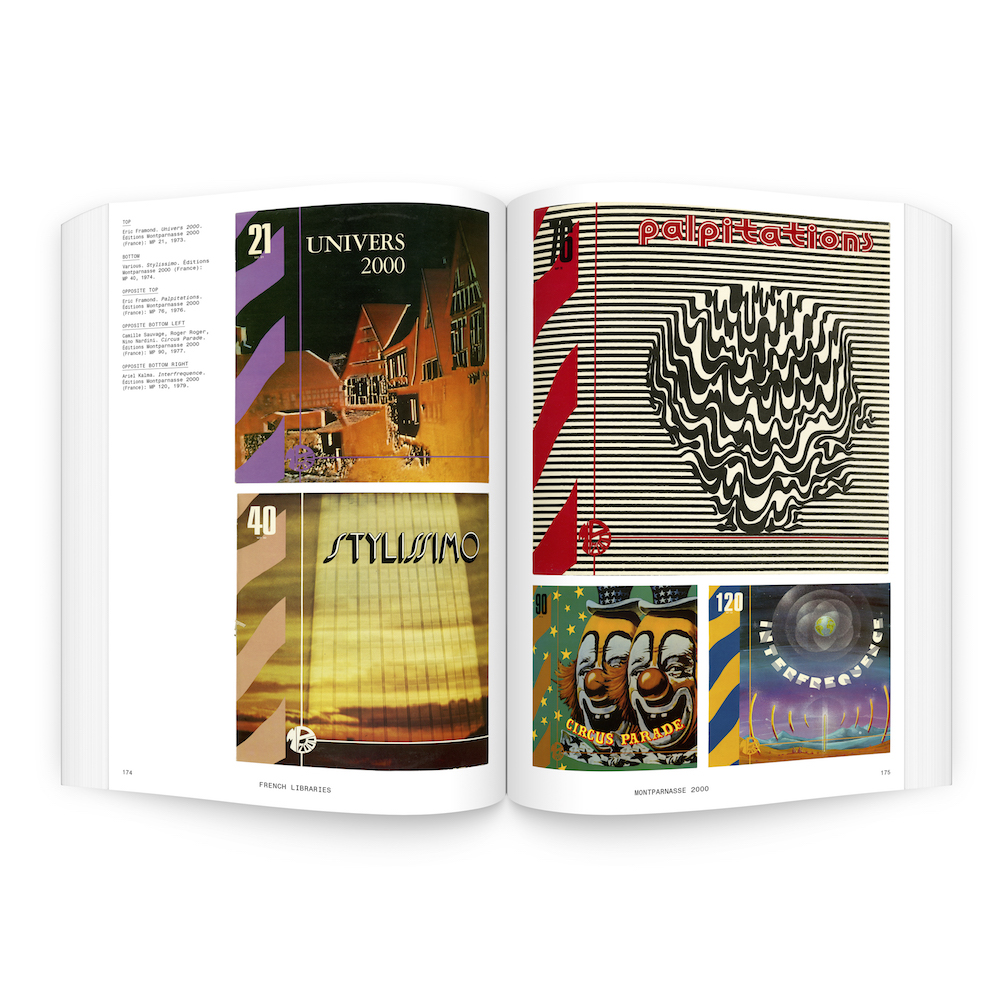

The sixties and seventies dominance of European music libraries is notable; Hollander puts this down to the influence of US musicians’ unions, which disapproved of its members surrendering their rights to library buyouts. So Unusual Sounds progresses through chapters on seminal libraries and luminaries such as Britain’s KPM (which featured composer talents including Hawkshaw, Keith Mansfield and John Cameron, and produced countless iconic themes, synched across sports shows including Grandstand and soft porn films like Emmanuelle); Germany’s Sonoton (founded by pop hitmaker Gerhard Narholz in 1965, and developed into an international label); Italy’s Flipper, CAM and Octopus; and France’s snazzy Montparnasse 2000 (named after its Paris arts district birthplace, in 1968).

“Somehow, library music and its mythologies feel more weirdly persuasive than ever”

The interviews here definitely pore over obsessive details, though they’re also spiked with smart soundbites; as Italian library music don Romano Di Bari explains: “Film music you write [based on] images already existing, but with library music, you are blind. You just work with your imagination.”

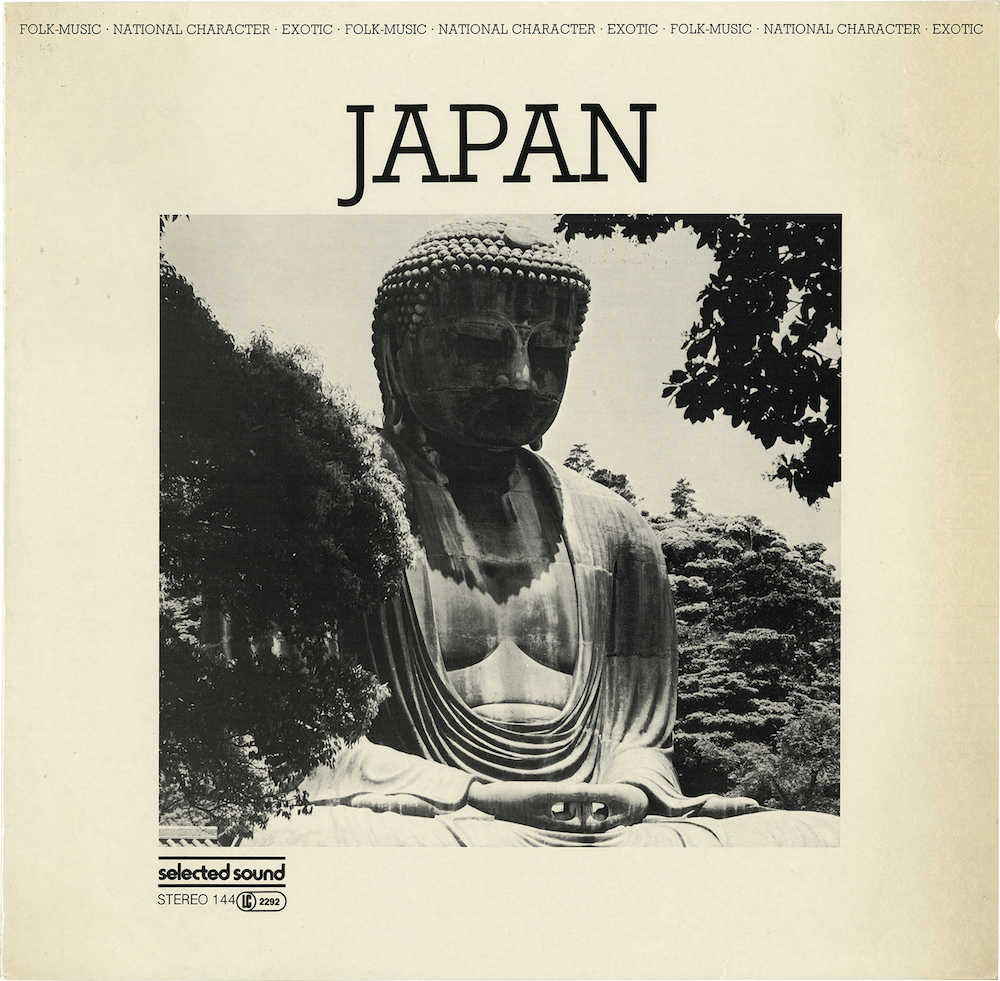

The record visuals then seize the imagination in their own right. Rather than revealing the composers’ identities, these library music sleeves are also all about summoning a mood—through futuristic graphic design, “exotic” imagery (these libraries frequently referenced non-Western sounds and subverted them into something else), poppy expressionism (the instant appeal of 1973 collection Jingles from Brit library Themes International), glamour or sleaze in heavily saturated colours. KPM’s records were also recognizable for their “greensleeves”, while Sonoton presented some of the most outlandish artwork—I’m still transfixed and horrified by the sleeve for Walt Rockman’s 1980 Pollution, which depicts a young child (actually Gerhard Narholz’s son) eerily asleep in a gas mask, clutching a doll. The illustration befits Rockman’s otherworldly/nightmarish electronic drone tracks, some of which can be heard online.

Ultimately, Unusual Sounds leads us deep into the archives and leaves us to continue our own explorations. Hollander equips us with plenty of fascinating leads and recognizable names who emerged from library realms (Delia Derbyshire, Fabio Frizzi, Piero Umiliani, Jean-Jacques Perrey and the KPM Allstars who now play live sets of classic themes). Somehow, library music and its mythologies feel more weirdly persuasive than ever. File under: out-there.