There is a marked upswing in the number of women artists participating at the Venice Biennale (11 May to 24 November) in 2019, titled May You Live in Interesting Times. The corollary is, it seems we do. Forty-two of the seventy-nine artists taking part this year are women—that’s 53%. In 2015, the number of solo female participants was 33%, and in 2017, 35% of all participating artists were women. It’s worth noting, that figures only reflect those who have identified as male or female, and doesn’t account for other genders.

The 2019 statistics indicate not only that commissioners are paying closer attention to the representation of gender but that the kind of exposure that women artists are getting is changing: of the forty-three National Pavilions presenting a single artist at the 58th Venice Biennale, some twenty-six are women—an impressive 60%. With a strong female-fronted voice 2019 is an exciting time for everyone, but particularly mid-career women artists who often hit a plateau elsewhere in the commercial and institutional art world. The youngest participant in this year’s Biennale is twenty-nine, and is the only artist under thirty being exhibited. The artists are getting older, but the audiences are getting younger, as “more than half of them are under twenty-six years of age”.

According to statistics compiled by the Freelands Foundation in 2017, 50% of women selected in the last ten years to represent Great Britain have been women—this year the mantel is picked up by Cathy Wilkes, curated by Zoe Whitley, (who returns from Italy to start her new role, working alongside the Biennale curator Ralph Rugoff at the Hayward Gallery

).

Perhaps most excitingly, women have made history this year: Pakistan selected Naiza Khan to represent the country’s first ever appearance at the Biennale, and Shu Lea Cheang will be the first ever woman to represent Taiwan.

Read more about Khan and Cheang—and the other women artists making this Biennale the most exciting yet—below.

Charlotte Prodger, Scotland

It’s been quite a year for the forty-four-year-old Prodger, with a Turner Prize and now a pavilion to her name. Using her experiences, research and, often, her iPhone, Prodger explores the “queer wilderness”, drawing analogies between landscapes and identity, gender and geography, informed by her upbringing in rural Scotland. She speaks openly about queerness in her work and outside of it. At the Scottish Pavilion, she will present a new video work.

Shu Lea Cheang, Taiwan

Shu Lea Cheang is the first woman to exhibit her work at the Taiwan Pavilion as a single artist. The artist, born in 1954, has been a pioneer of net art, using film, action and installation to bridge that ever-increasing gap between technology and humanity. She made her name in the 1980s in New York, and she was the first ever artist to be commissioned by the Guggenheim to create a web-based artwork. Her online platform, Brandon (1998-9), addressed the horrific rape and murder of transgender man Brandon Teena. Her art continues to be engaged with activism and anti-racist politics, subjects bubbling over at this Biennale.

Laure Prouvost, France

After working with Martha Kirszenbaum in Los Angeles on her acclaimed solo exhibition at Fahrenheit, Prouvost enlisted the young curator for her presentation of Deep See Blue Surrounding You /

Vois Ce Bleu Profond Te Fondre at the French Pavilion. The film follows a journey on horseback through France, to Venice, using metaphor and magic, typical of the Turner Prize-winning artist.

Naiza Khan, Pakistan

In February it was announced that Naiza Khan would be the first artist to represent Pakistan in Venice. Her work explores life on Manora Island, revealing links between Venice and Arab, Persian and Indian history, through trade routes and empires. The artists began travelling to Manora for time to think and space away from the turbulent and restrictive atmosphere in Karachi, where she is based. From there, ideas began to emerge, and the project evolved into “not just views or scenarios of a city but it’s also very much about a subjective experience of me as a female body traversing a space which is a very public space, which is a very gendered space. So I see that notion of the body very much present in this work.”

Iris Kensmil, Holland

Iris Kensmil describes her work as “the painting of memories”, with which she refers to making the history of black people visible. At the Dutch Pavilion, a mural by Kensmil will cover the walls with seven black female intellectuals: journalist Claudia Jones, feminist science fiction novelist Octavia Butler, anti-colonial writer and surrealist Suzanne Césaire; communist and activist Hermina Huiswoud; black feminist Audrey Lorde, the Pan-Africanist Amy Ashwood Garvey; DJ and singer Sister Nancy and iconic feminist author and critic, Bell Hooks. In the context of the Dutch Pavilion, the past of colonialism, nationalism and modernism in Europe will be radically uprooted.

Cathy Wilkes, Great Britain

Wilkes follows on from Phyllida Barlow’s exhibition at the British Pavilion in 2017, and the Northern Irish artist is the twenty-second to have a solo exhibition at the Biennale. Every work presented will be entirely new: sculptures, objects and paintings, experimenting with materials and materiality. The British Pavilion is one of the most anticipated this year—perhaps a contender for the Golden Lion—also due to the intensity of attention on its curator, Zoe Whitley. “[Wilkes’s] inventiveness, curiosity and unique thinking have produced something as ambitious as it is captivating,” Whitley hints.

Kris Lemsalu, Estonia

Lemsalu’s world is one we want to live in: and so, apparently, does Sarah Lucas, art critic, Andrew Berardini, the curators, Irene Campolmi and Tamara Luuk, and a bunch of musicians—all part of her team of personal friends who have helped put the show together. At thirty-four, Lemsalu is one of the younger artists to represent her country, but her visual language is already solid, a fairytale landscape of ceramics, costumes and characters.

Tracey Rose, South Africa

Hilariously funny and politically trenchant, Tracey Rose‘s work to date has been rooted in physical performance, but at Venice, where she is part of a group presentation at the South African Pavilion, she’s doing something new, and getting behind the camera to direct the action in a “mancave” she’s creating to explore ideas about healing. As she relayed in a recent interview, “I have been asked for the last two Biennales. I said no because they were a mess. I’m not gonna put my name to that. I’m not going to endorse mediocrity.” This year she’s back, after participating for the last time twelve years ago, but it’s on her own terms of course. Her untameable and truly unique work will no doubt rattle a few cages.

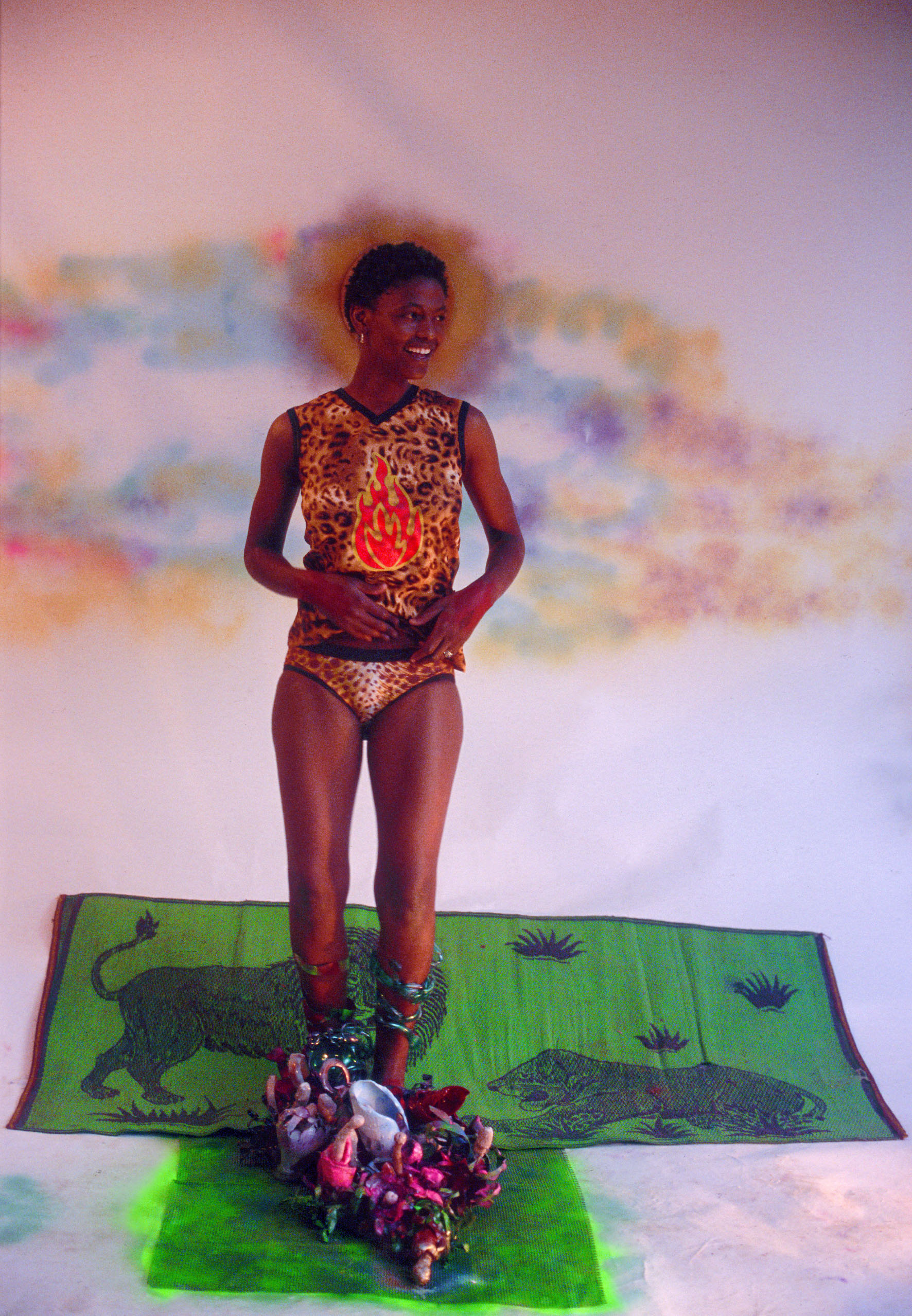

Kudzanai-Violet Hwami, Zimbabwe

Painter Kudzanai-Violet Hwami is part of a group exhibition at Zimbabwe’s Pavilion, reinterpreting the epic poem by the late African nationalist Herbert Chitepo, the leader of the Zimbabwe African National Union who was assassinated in 1975. Born almost two decades later, in 1993, Hwami left Zimbabwe aged nine amidst political turmoil and has lived in South Africa and the UK since. In her paintings, she finds creates a space for an identity that has been displaced, exploring sexuality, healing, rituals and family life.

Renate Bertlmann, Austria

At seventy-six, Bertlmann is finally getting all the recognition she deserves in Austria, a country that for a long time, shunned and censored her work. Now the grande dame of the feminist avant-garde, Bertlmann’s iconic works, old and new, will be part of her solo presentation. Erotic, funny, sexy and cool, Bertlmann is a role model who loves playing with roles and hierarchy, things we need to be reminded of, in Venice, and beyond.