The emergence of the word ‘vibe’ seemed to dominate 2021. The nebulous term can seemingly be used to describe anything from the mood of a party to a subculture, a TV channel to a whole city. It can describe a person, a food, a website, or even the entire world. In an end-of-2021 essay in the New Yorker titled The Year in Vibes, Kyle Chayka likened its sudden burst of popularity to “the Strasbourg dancing plague of 1518”.

What might the prevalence of the word tell us about the time that we live in? Its lack of specificity is arguably an accurate reflection of how little of the present we actually understand, no matter how hard we try. It’s an uncertainty that could be attributed to both post-pandemic shock and a constant stream of online data, from live news blogs to social media updates.

Just as we were getting our heads around the rise of vibes, an article published in February in The Cut sent readers into a tailspin. In A Vibe Shift Is Coming: Will Any of Us Survive It?, writer Allison P Davis explored how our cultural moment is in the process of a transition that doesn’t yet have a name. 2022, supposedly, is the year of the vibe shift.

The piece is primarily an interview with Sean Monahan, the trend forecaster who popularised the term ‘normcore’ in 2014 with the K-Hole collective (a group of New York based artists, writers and creatives). In the piece he reflects on the popular aesthetics of the last two decades, notably the switch from indie rock’s mid-aughts supremacy to a plural post-internet culture.

“Vibe’s lack of specificity is arguably an accurate reflection of how little of the present we actually understand, no matter how hard we try”

Most significantly, Davis and Monahan discuss the popular explosion of trend forecasting in recent years. In 2022, the corporate activities of identifying and predicting consumer patterns spilled out of the opaque secrecy of the boardroom and into the wider consciousness. Increasingly, trend forecasting is a task that artists, writers, and creatives are also undertaking.

Can almost anyone with an art school degree now lay claim to an uncanny ability to assess the vibe? It is arguably an intersection that K-Hole pioneered back in the early 2010s. They came of age with the rise of DIS magazine, another art collective with a tongue-in-cheek sensibility and an acute awareness of the inherent capitalist contradictions of the so-called utopian internet age.

With K-Hole, Rhode Island School of Design graduate Monahan (he studied painting) combined the commercial processes of trend forecasting with the aesthetics of post-internet art. The group produced reports decorated with bold slogans about global youth culture. The confluence of styles was reminiscent of everything from Situationist pamphlets to the early days of Vice Magazine, all repackaged in InDesign for Adidas executives. Naturally, K-Hole worked with brands and institutions including MTV, Stella Artois, and Kickstarter.

“In a precarious time of frequent change, it is natural for speculation to dominate our thinking”

K-Hole folded in 2016. In interviews Monahan has spoken of the challenges they faced in making their research profitable. He now runs 8-Ball, his own consultancy firm. Similarly, his former-colleague at K-Hole, Emily Segal, runs Nemesis, a design and strategy consultancy group with clients including Nike, Louis Vuitton and Off-White. She is currently selling a crypto coin to fund the writing of her second novel, which focuses on the pitfalls of trying to write fiction while working in a corporate environment.

For many artists and writers, trend forecasting is a way to earn greater sums of money through collaborations with brands and corporations. The New Yorker’s Chayka suggests the slow death of print media’s profitability as the reason behind the move by creatives to monetise their cultural nous. “A way to monetise your clout as a writer is to sell your expertise,” he explains. “In other words, it’s the economics of media that makes a cultural observation as likely to show up in a corporate trend report as a magazine essay.”

Charlie Robin Jones, a writer and former editor at Real Review, the Guardian and Dazed, undertakes consultancy work in a professional capacity alongside his work as a journalist. He explains that maintaining a division between the cultural analysis that he carries out in both a creative and a more commercial context can be difficult.

“I’m always feeling where the line is, enforcing it, because it gets less clear by the day,” he admits. “I love both parts of my work, and see them as feeding each other, to the point where I can’t say which is the day-job. Is this modern? It feels so.”

“Can almost anyone with an art school degree now lay claim to an uncanny ability to assess the vibe?”

The skills required by trend forecasting (analysis, research and prediction) are exactly those often inherent in a cultural workforce of artists. The seemingly contradictory nature of this phenomenon, from creativity to commerce, might be contained less in the tasks than in the outcomes. You can’t eat your own knowledge, and trend forecasting is able to offer economic stability to supplement a creative career that is notoriously underpaid and unreliable.

Could trend forecasting even offer a fairer model for a society that wishes to value the work of its writers? Some creatives share their cultural predictions directly with consumers. In their Substack newsletter Blackbird Spyplane, California-based culture journalist Jonah Weiner and Erin Wylie, a talent scout for Apple’s design team, collate their reflections on design with cultural observations. The newsletter is written in a idiosyncratic TOV (industry speak for tone of voice), best characterised as a hyperactive soup of colloquialisms, and is billed as a unique insight on the contemporary moment from the heart of Silicon Valley.

Meanwhile, the artist Brad Troemel uses social media and digital publishing in an attempt to critique faddish cultural zeitgeists. He produces video reports that aim to cut through the ‘babble’ of capitalist culture, taking aim at the art market and at crypto-currency. His work frequently takes on and makes fun of trend forecasting, although his ability to mockingly spot trends could be mistaken for the real thing. He promises to make clear what lies beneath the bluster of marketing, although much of his content is for paid subscribers only.

Philosopher Peli Grietzer, author of popular academic paper A Theory of Vibe, sees the growth of trend forecasting in creative circles as just another way of understanding the world around us. “Social media means we’re experiencing society from both a bird’s-eye view and in real time,” he explains.

“For many artists and writers, trend forecasting is a way to earn greater sums of money”

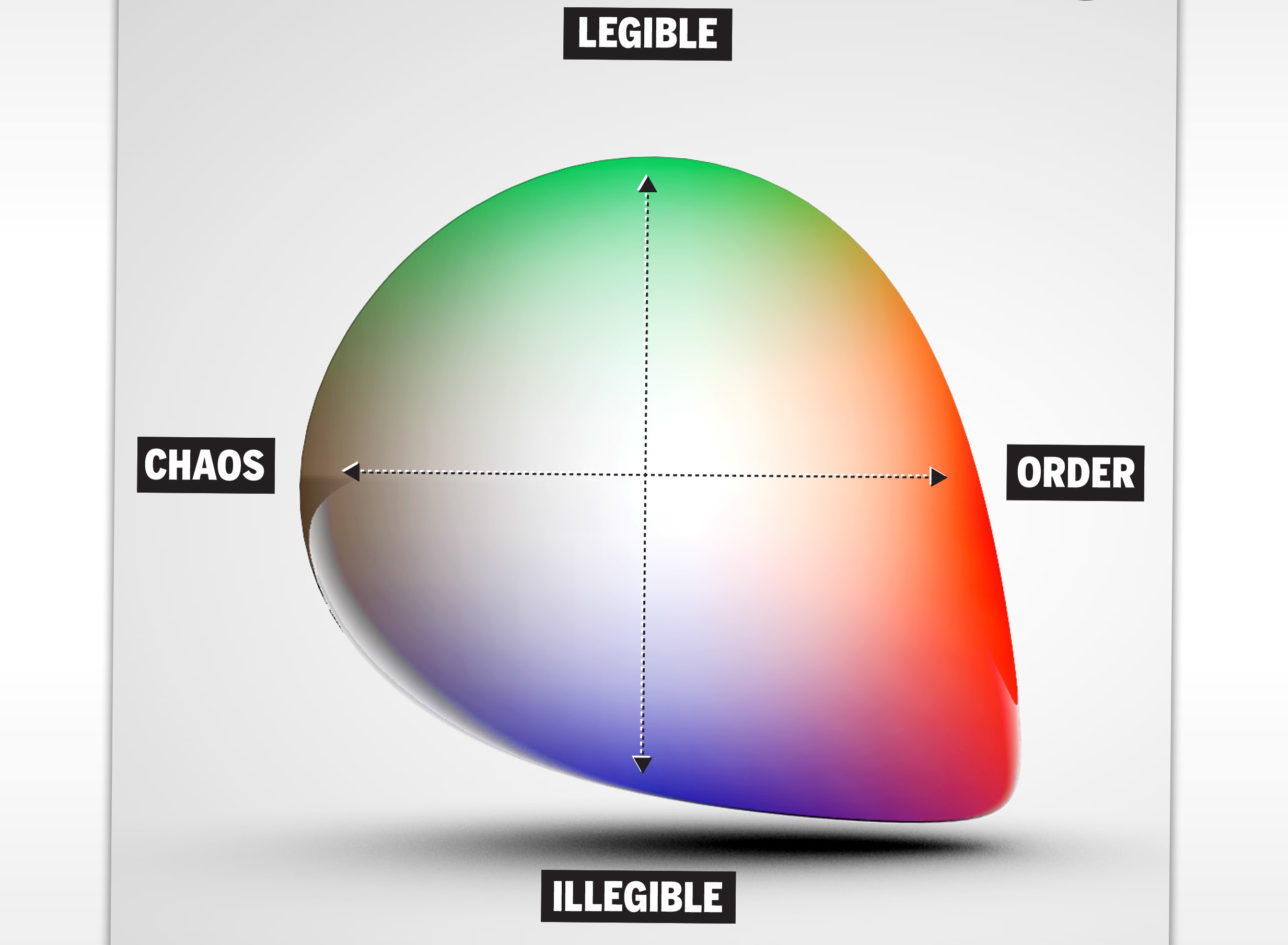

Our constant exposure to new data means we are trying to give coherence to something that is legible but hard to process, which has given rise to the amorphous notion of the ‘vibe’. The algorithms render, distribute, and sell cultural objects, but the human brain is slow to process this new data-driven reality. Trend forecasting make sense amidst the chaos.

There is also something to be said for the gratification gained from engaging in unscientific processes. The joy of predicting the next trend is comparable to the predominance of online content about astrology: both provide neat boxes, and conceptual structures into which a complex reality can be squeezed. In a precarious time of frequent change, it is natural for speculation to dominate our thinking.

Change is inevitable, but the present moment remains overwhelming for many. One thing that the recent stream of emergencies has revealed is how vital the work of artists and writers is to making sense of the world around us. In the moments of freedom from economic necessity, it allows us to reflect, sensorily and intellectually, on a chaotic reality and its strange impulses: to understand it and to think about how it could be different.

Yet as the economic consequences of pandemic management take hold, it will be even harder for powerful art to emerge. Perhaps there are fairer models for a society that truly wants to value the work of its artists and writers than the ones currently on offer?

Ed Luker is a poet and writer based in London