Over in Zurich sits a small, unassuming publisher that, in the near-two decades since its foundation, has quietly forged a path for itself as a bastion for a distinctly hand-made approach and small-batch printing. Despite its small print runs—each edition has just 100 copies—Nieves has a well-deserved reputation for uncovering the most interesting, strange and smart approaches to drawing, illustration, photography and graphic arts. Co-founded by Benjamin Sommerhalder co-founded the publisher in 2001, its aim is to create “affordable, quickly made and simply distributed publications that could be published on a regular basis,”

The artists who it has worked with since range from almost unheard of emerging talents to the likes of Miranda July and Harmony Korine. The latter published the companion to his latest film, The Beach Bum, with Nieves—a title called Key Zest, which features dialogue spoken by the film’s central character Moondog, alongside snippets of his “poetry”.

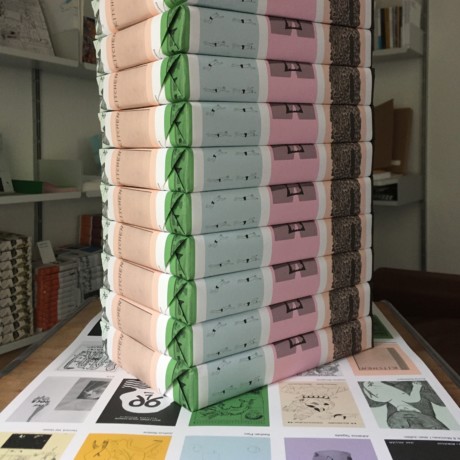

The Nieves zine publishing model is nimble thanks to its smart approach to uniformity: 100 copies per print run, with each edition printed using black and white photocopy on a paper colour selected by the artists, with every zine sold for $8 (around £6). The zines often sell out quickly but, at the end of each year since 2004, the publisher releases a boxset of the past twelve months’ entire zine output. These cost $100, and only twenty of them are created. Again, the boxes sell out fast.

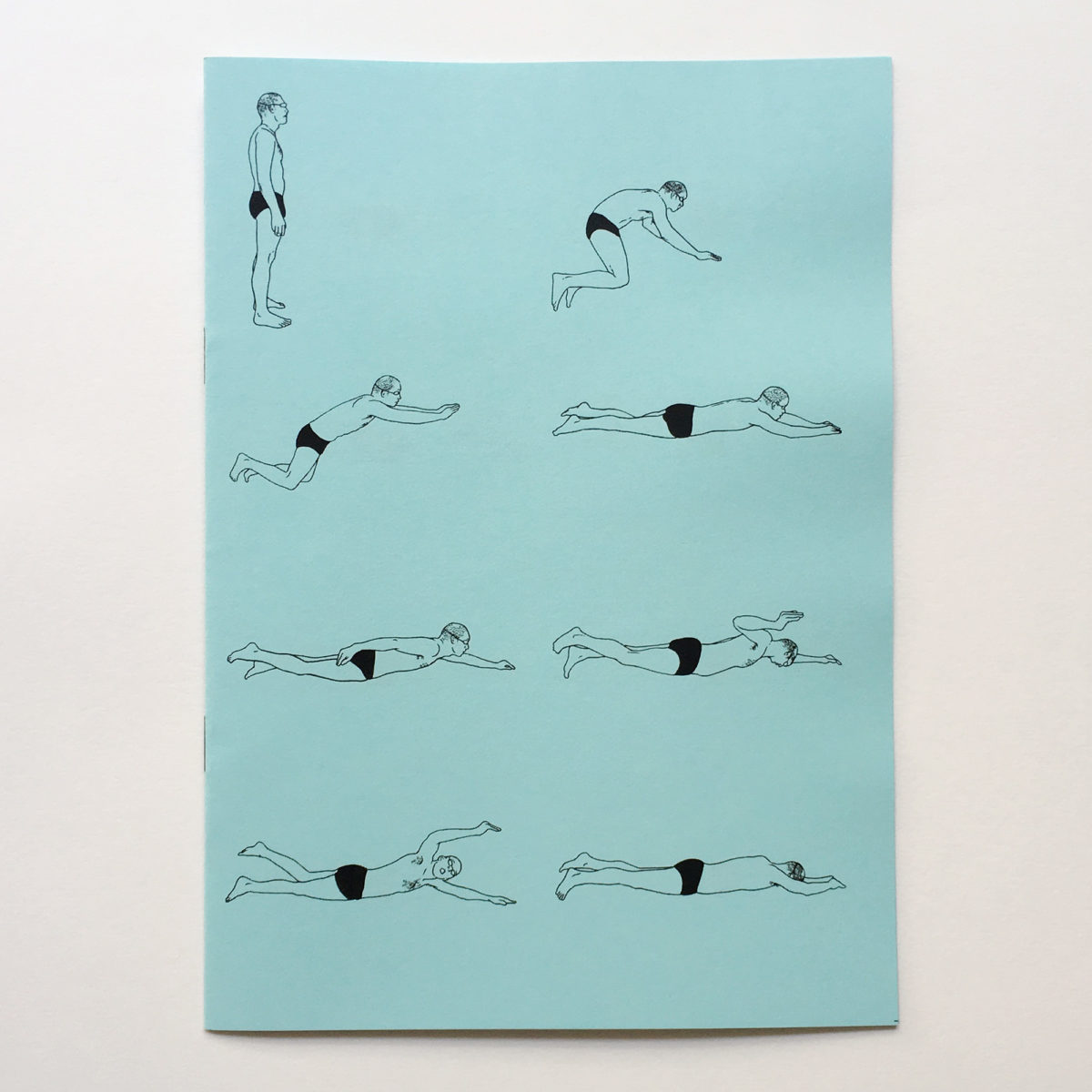

The 2019 Zine Box, as with previous years, demonstrates the weird, wonderful world of small-scale zine publishing, and what makes it such a crucial discipline when it comes to gentle humour that often uncovers complex issues through image-making. The breadth of approaches is extraordinary, despite the apparent formal similarities in place thanks to the Nieves zine guidelines for paper, printing technique and cover price.

“We love work that is on the edge of art and design; of high and low; beautiful and ugly; or on the edge between professional and amateur”

“The selection of artists is a very individual, personal one,” says Sommerhalder. “There’s not a big concept of who to feature—it’s also a web of people we’ve worked with before, friends of friends and new discoveries. The focus is on contemporary drawing but it doesn’t exclude other fields such as photography, collage or painting. It can be famous or unknown artists—what we look for is an original, fresh and surprising way of working and a great drawn line.” He adds, “We love work that is on the edge of art and design; of high and low; beautiful and ugly; or on the edge between professional and amateur.”

The approach to publishing, then, is both amorphously specific and deliciously broad, meaning that each box reflects the multifarious styles of the artists published in one year. “We don’t set out to have a homogenous set, but treat each zine individually,” says Sommerhalder. ‘What holds the zines together, or gives them a familiarity that makes them recognisable as a Nieves zine, is the curation, the style and also the specs on size, paper, printing, and so on.”

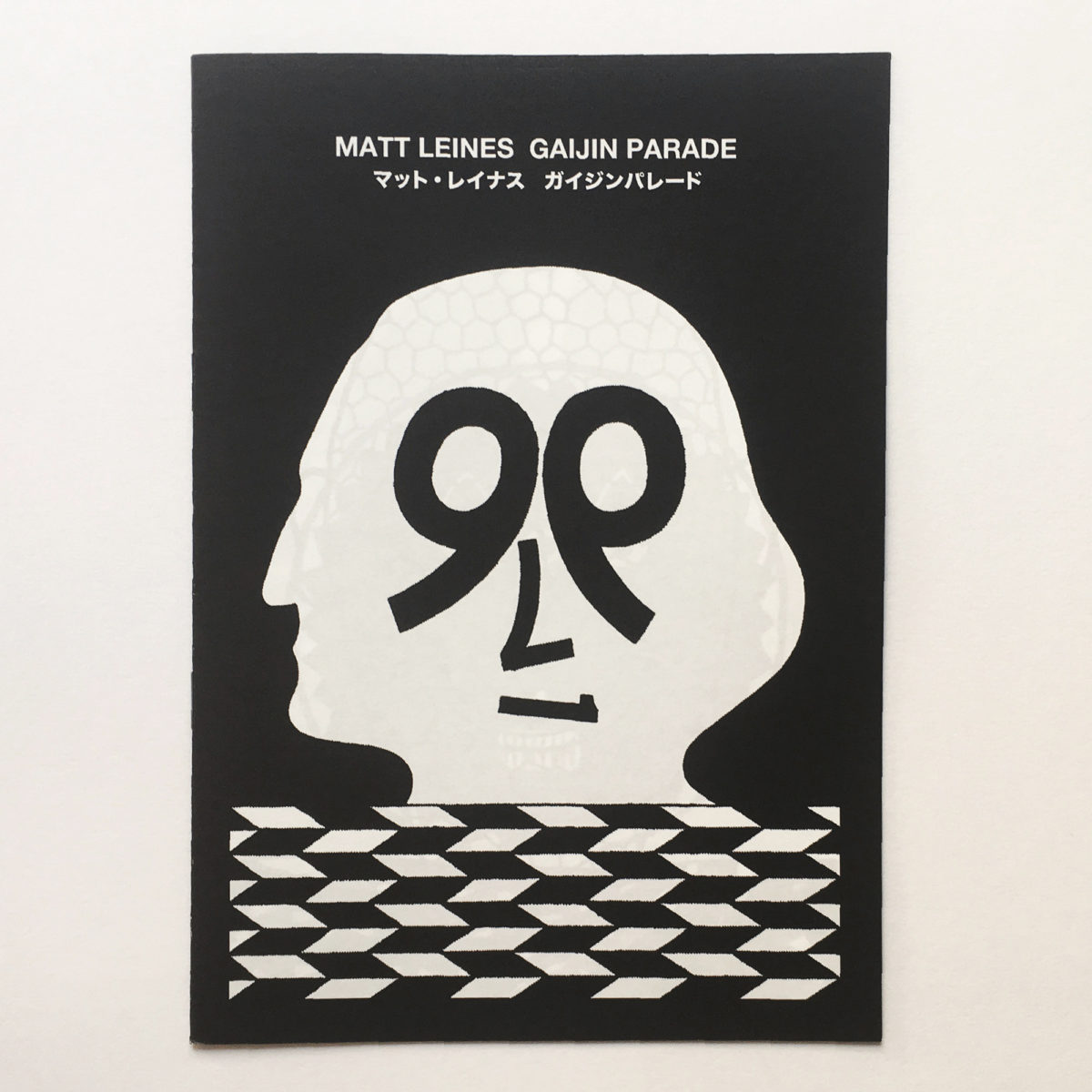

The 2019 edition includes work by Yannick Val Gesto, Johanna Tagada, Joshua Abelow, Emma Kohlmann, Nathaniel Russell, Heather Benjamin, Arisa Odawara, Umar Rashid, Micah Lexier, Mrzyk & Moriceau, Jean Jullien and many more. It also features a publication by Sommerhalder himself, celebrating Nieves’s very own ghost (he features on their logo), Knigi, who haunts the walls outside the publisher’s office. It shows the young ghost reach the “birthnight” (as opposed to birthday because, you know, he’s a ghost) that marks the age at which human children usually learn to read. His aunt gives him a book as a gift, but he finds that it’s empty—the pages are just white—and the wee ghoul decides to investigate, ultimately discovering the joy of reading.

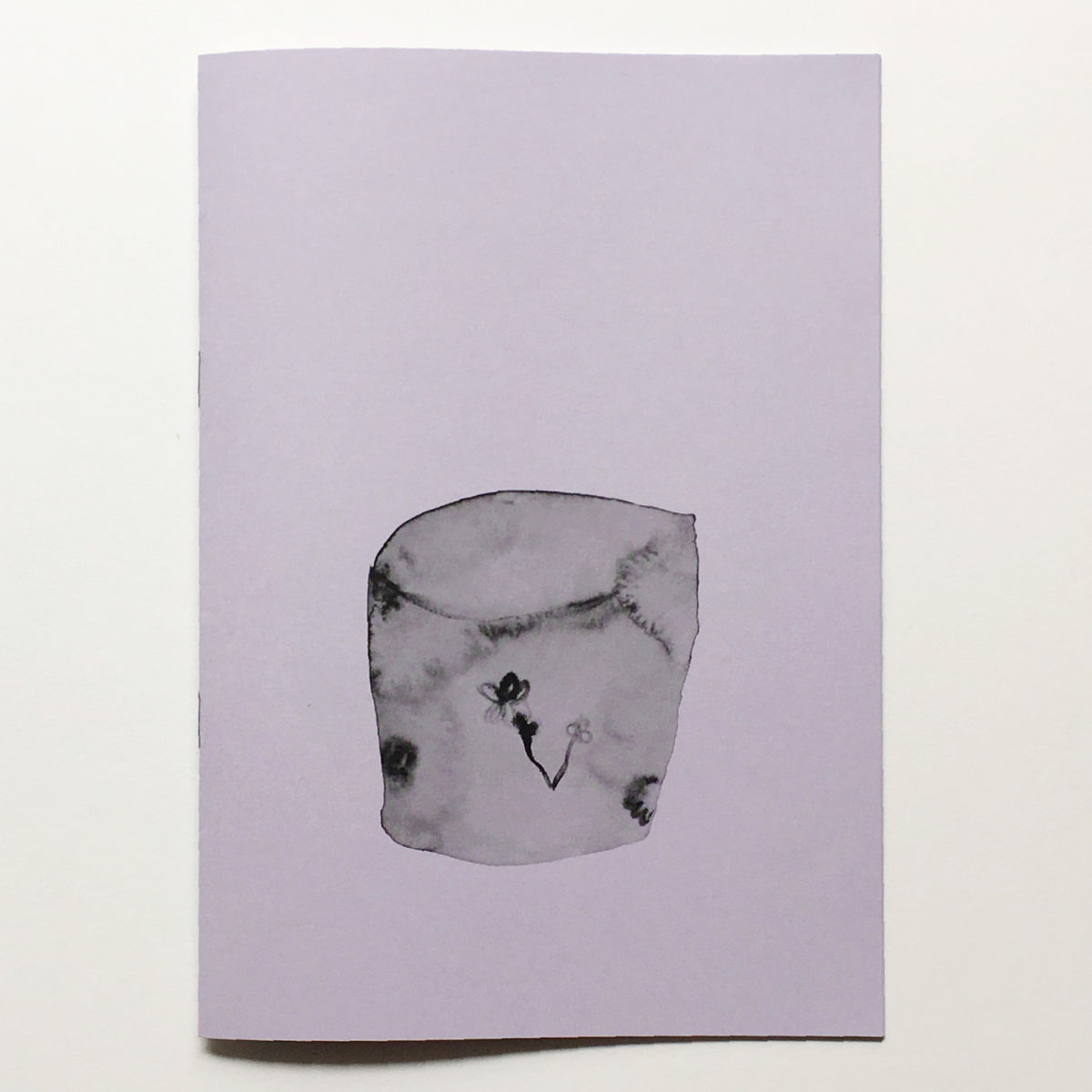

Many of the zines are similarly lighthearted and personal, such as Tea Vessels by Johanna Tagada. The broad focus of the artist—who is based between London, Alsace in France and rural Tamil Nadu in India— is around art’s relationship to daily life. The zine features a series of Japanese watercolour paintings on paper, an ongoing body of work begun in 2017 as a daily painting practice when Tagada was editing Journal du Thé—Chapter 1. She created a painting every day of an object relating to tea culture, in just twenty minutes, during which time she also enjoyed a cup of tea.

“What we look for is an original, fresh and surprising way of working and a great drawn line”

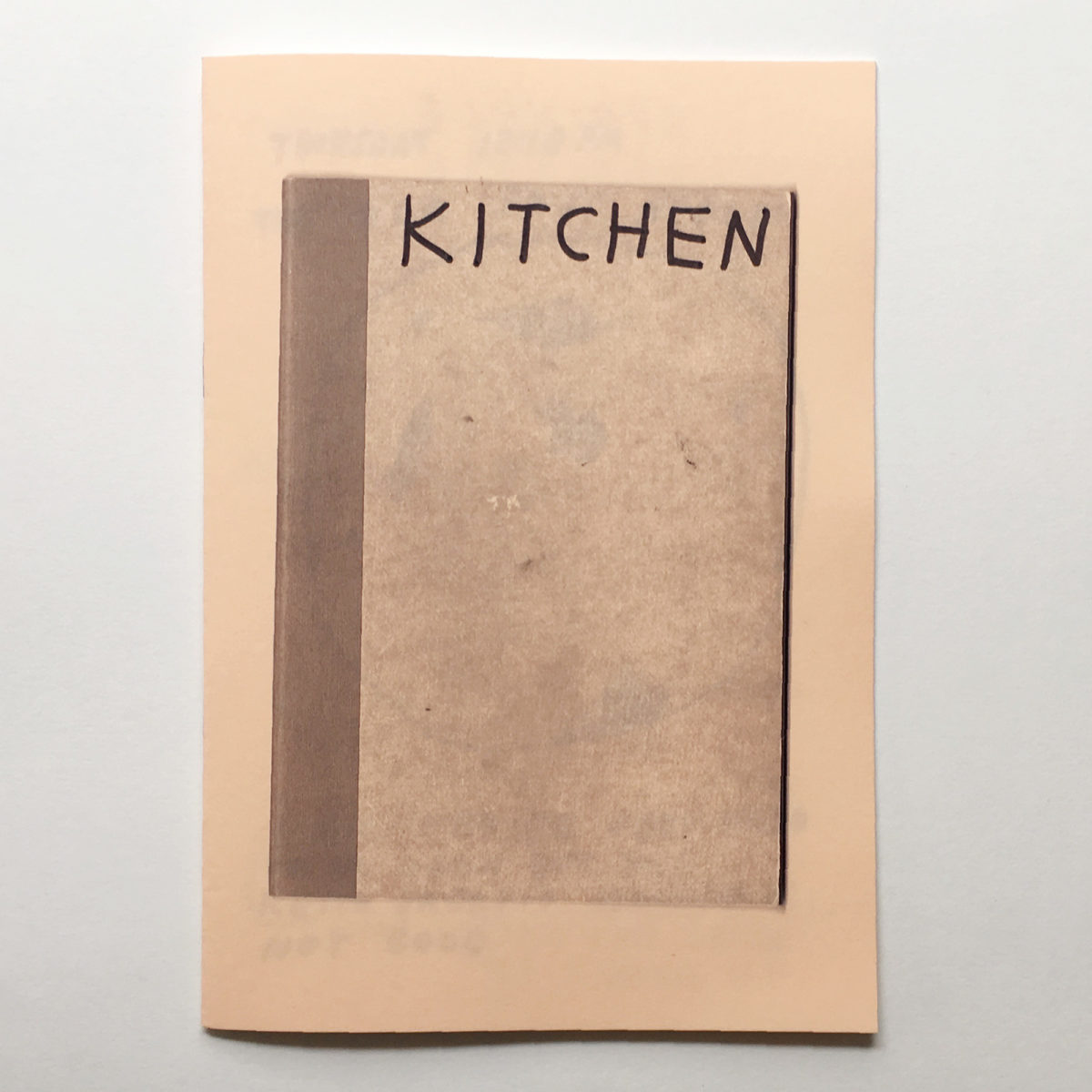

Kitchen Diary, by Nathaniel Russell, shares that focus on domesticity. “I started keeping a small sketchbooks in the kitchen, to be used only in the kitchen, so it would be easier to record thoughts and draw things while I make food for my family,” he explains. “It was an exercise in being present and not letting moments slip away that may seem small at the time.” His zine shows a selection of drawings and writings from the first month of keeping the sketchbook.

- Tea Vessels, Johanna Tagada

- Dream Sketchbook, Emma Kohlmann

Other zines in the box, meanwhile, tackle more complex, thorny issues. Pathological High Mood, for instance, by Karoline Schreiber shows fifteen drawings from the ongoing series Drawing Account. Her images investigate the strange other-worlds of the unconscious; through depictions of “misplaced body parts, distorted figures, and hybrids of people and plants performing strange activities,” as the publisher puts it. The overall drive behind this is to show that there are dreamlike qualities in what might seem weird or deformed, aiming to “normalize the monstrous.”

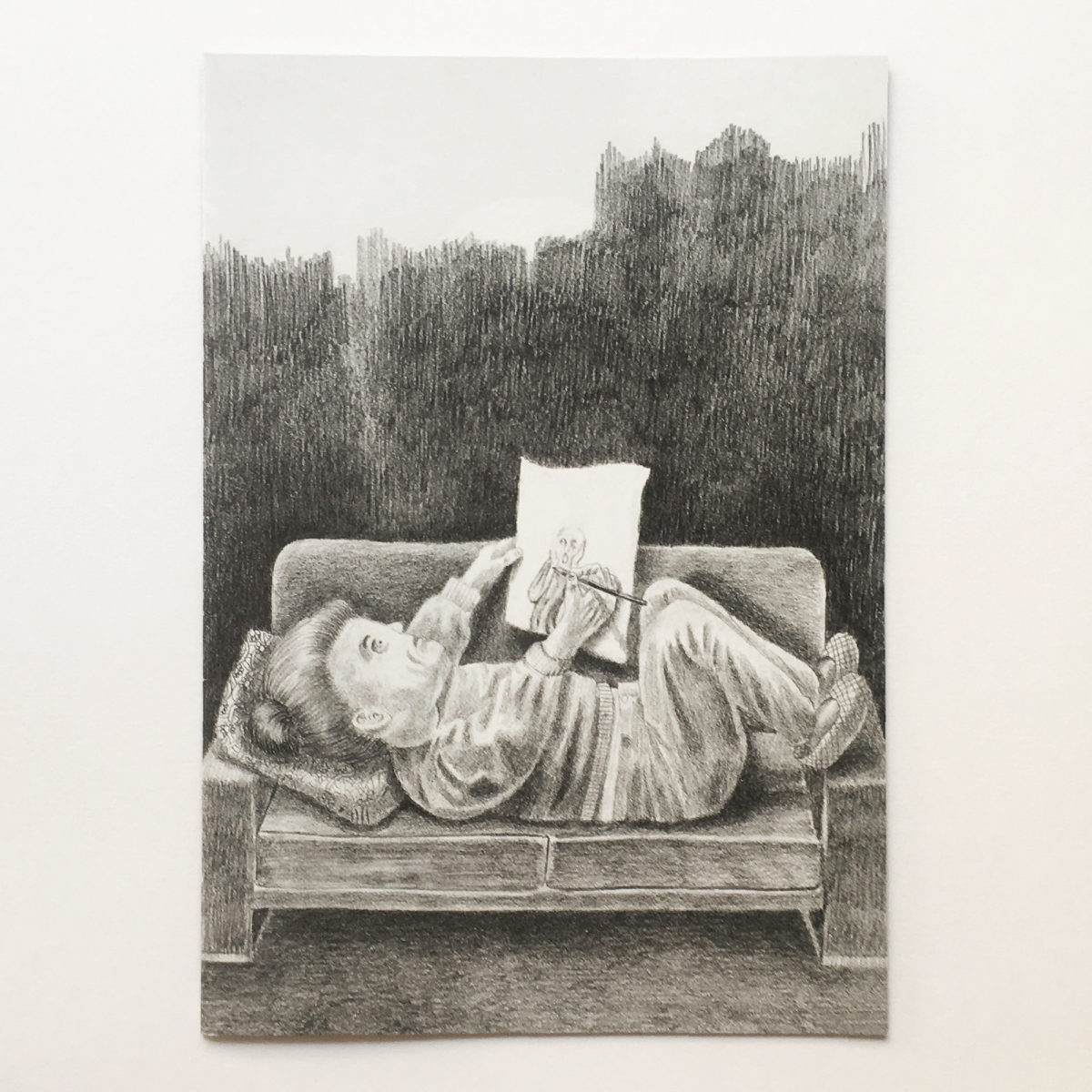

Dream Sketchbook by Emma Kohlmann, meanwhile, confronts the inherent difficulties of creativity, or of translating what we see in the mind’s eye into concrete visual output. The artist, based in a small town just outside Massachusetts, created the series of drawings in the zine using crayon, to “represent recurring ideas that appeared to her in dreams but never seem to actualize themselves into works of art”. Well, happily for Emma and the other artists included in the zine box, they have now.

Nieves, Zine Box 2019 by

VISIT WEBSITE