Bombarded with images of collapsing ice shelves, stranded polar bears and burning rainforests, it’s easy to despair about mankind’s systematic abuse of the environment. But what happens when nature fights back? In their recent show Another Funny Turn at Block 336 in Brixton, Sarah Cockings and Harriet Fleuriot treated nature as a force to be reckoned with. The viewer was led on an adventure into a bizarre rural installation in the darkened basement, where topiary smileys loomed over the crowds, the walls seemed to breathe and outlandish purple plants resembling fuzzy kebabs rotated frenetically. Into this madness the artists inserted numerous videos of themselves in camouflage onesies clumsily performing futile feats in the great outdoors.

“There’s a transformative opportunity of stepping into a space like that and reconfigure the normal rules of behaviour and interaction,” says Fleuriot. “We talked about the idea of nature as a site of liberation. When you’re a teenager you don’t have a feeling of the sublime, it’s much more about a place you can smoke, drink, take drugs and roll around. Also there’s no authority; nature is the authority and it’s not judging you.”

“When you’re a teenager you don’t have a feeling of the sublime, nature’s much more about a place you can smoke, drink, take drugs and roll around”

This was played out at Block 336 in the tactile environment where adults threw off inhibitions, rubbing themselves against spinning airbeds and stroking the slimy ziggurat-shaped fountain. The sense of nature as something possessed lent the setting a creepy air, but in a hammy horror, Wizard-of-Oz-haunted-forest way, amid a plethora of other references: from gaming culture with its heroic quests through grandiose landscapes, to the gendering of nature, to catastrophic thinking, to our tendency to look to the universe for guidance. And metaphorically, the artists were also using nature to evoke the disorientation of growing older.

“Nature is essentially really indifferent to us,” says Cockings, pointing to the overgrown chalk quarries, tin mines and other industrial relics that formed the backdrop to their videos. “Among the many ideas in the show, we were talking about nature reclaiming these sites and the fact that we also can’t stop ourselves from getting older, that’s nature taking its course.”

There is, of course, an august lineage of art that deals with the theme of Vanitas, but one of the most shocking depictions of nature’s inexorable march is Damien Hirst’s 1990 installation A Thousand Years. Relentlessly unemotional and minimalist in appearance, the work consists of two glass vitrines: in one, maggots hatch inside a white cube then fly into the neighbouring space, where they feast on a rotting cow’s head and either mate or are zapped by an insect-o-cuter. As a metaphor for the human condition through the birth-to-death cycle of flies, it is terrifying and grotesque. It’s also gripping—Francis Bacon was apparently transfixed when he saw the work. And let’s not forget about the entire menagerie of animals that Hirst has suspended in tanks of formaldehyde, beginning with his notorious shark in 1991, animals so vivid that they appear to be trapped in a no-man’s land between life and death.

Fellow YBA Marc Quinn has also toyed with nature to create what might be seen as zombie plants. Experiments with freezing liquid silicone to preserve his famous blood head, titled Self, led to the discovery that he could halt the natural decaying process in plants. As a result, he began creating sculptures of flowers in vitrines of subzero silicon that appeared to be frozen in time. The series culminated in his 12.7 metre-long installation Garden (2000), consisting of an Edenic profusion of tropical flowers from different parts of the world, that could never naturally grow together, artificially kept in eternal bloom in a refrigerated tank. Turn the power off and these already dead flowers would turn black like the wraiths in a fantasy film.

Perversion in nature is not peculiar to contemporary art. Consider Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights: the erotic central panel shows men and women disporting themselves with oversize fruits and birds in a surreal fantasy landscape, while the final panel depicts the damned among wonderfully imaginative hybrid animals that are cannibalizing each other. Even if the Dutch painter intended his famous triptych as a moralistic allegory, as some believe, who would choose staid paradise when Earth and Hell look so much more enticing?

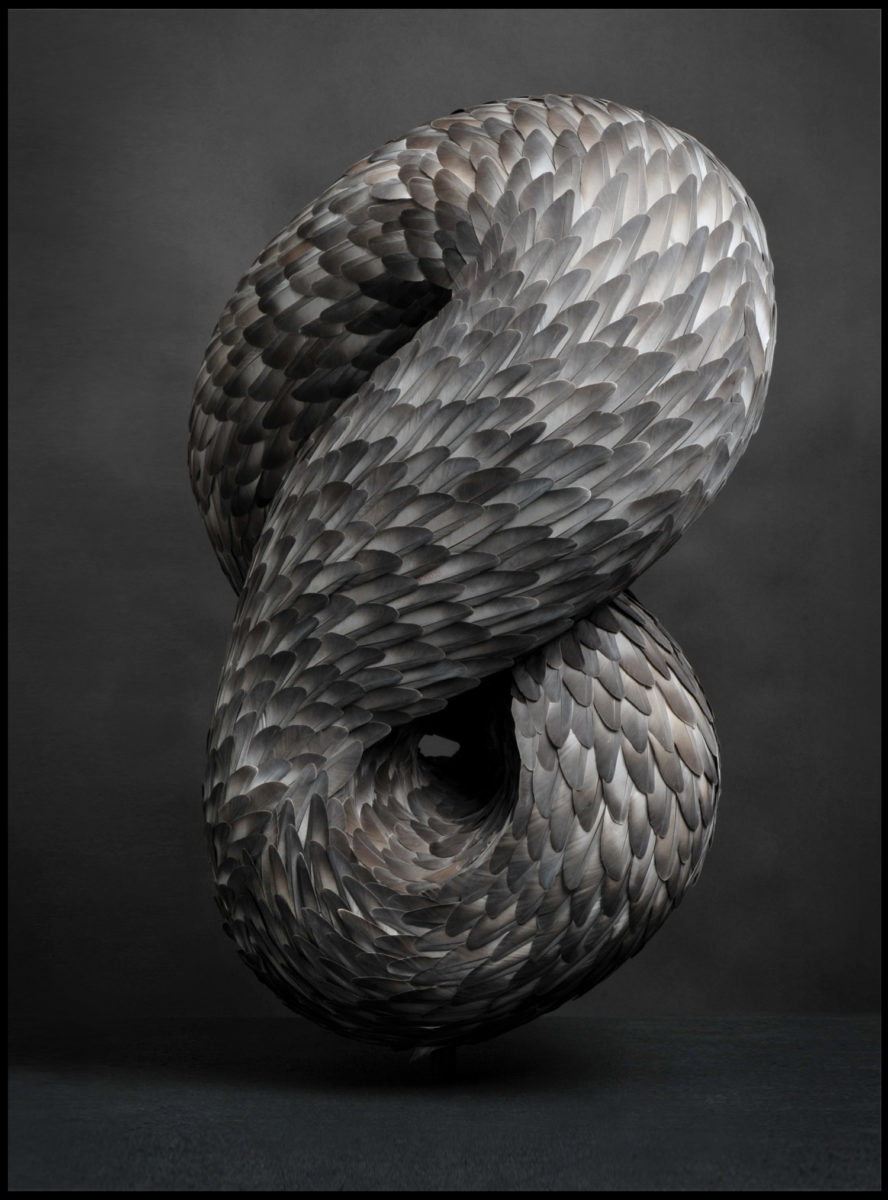

This idea of nature as freakish and enthralling has been taken up with gusto by artists such as Raqib Shaw, who tantalizes with intricate, hedonistic paintings of the physical world inhabited by kitsch monsters and fabulous beasts. The sculptor Kate MccGwire, meanwhile, uses nature as her medium, to construct shapeshifting, mysterious forms from feathers. Manipulating different parts of the plumage, her creations can have the delicacy of ash or the menace of a slick gushing from a pipe, invading the domestic space.

But beyond ideas of mutation and putrefaction, nature is perhaps most alarming and marvellous in its untamed wilderness. Turner’s magnificent paintings of tumultuous seascapes offer a visceral evocation of nature’s sheer might. John Akomfrah’s stunning 2015 film Vertigo Sea takes up this epic vision, portraying the roiling ocean as a capricious protagonist that swallows up bodies of migrants and slaves and is itself threatened by human ravaging of the environment.

“Beyond ideas of mutation and putrefaction, nature is perhaps most alarming and marvellous in its untamed wilderness”

Artistic depiction of nature has increasingly focused on ecological devastation as the scale of the crisis becomes more evident. But one might take solace in the portrayal of nature’s resilience, which one finds, for instance, in the recent work of the sculptor Anna Reading. For her show Pothole at Standpoint Gallery, the inhospitable Isle of Staffa, a basalt volcanic rocky outcrop off Scotland was her muse. “It’s a place where the organic is very much in control,” she says. “It’s almost like it’s washed clean of us. It’s one of the most uninhabited places we can go. You can’t build there because the sea will literally wash you away, but it’s also a site for things to congregate on, like limpets and puffins.”

Reading’s weathered-looking sculptures bore traces of human presence like a Puffa jacket dangling from one antenna-like structure, but the arid environment exuded a sense of foreboding, heightened by the occasional disembodied eye peering from an unfamiliar form, perhaps in the wake of some disaster. “Maybe that’s our fear attached to aliens, of life carrying on without us. It is a space of danger; I do want it to have a feeling of unease and disturbance,” Reading said about the show, but added, “equally, I want it to be quite hopeful and this idea that growth continues and big shifts can happen.”