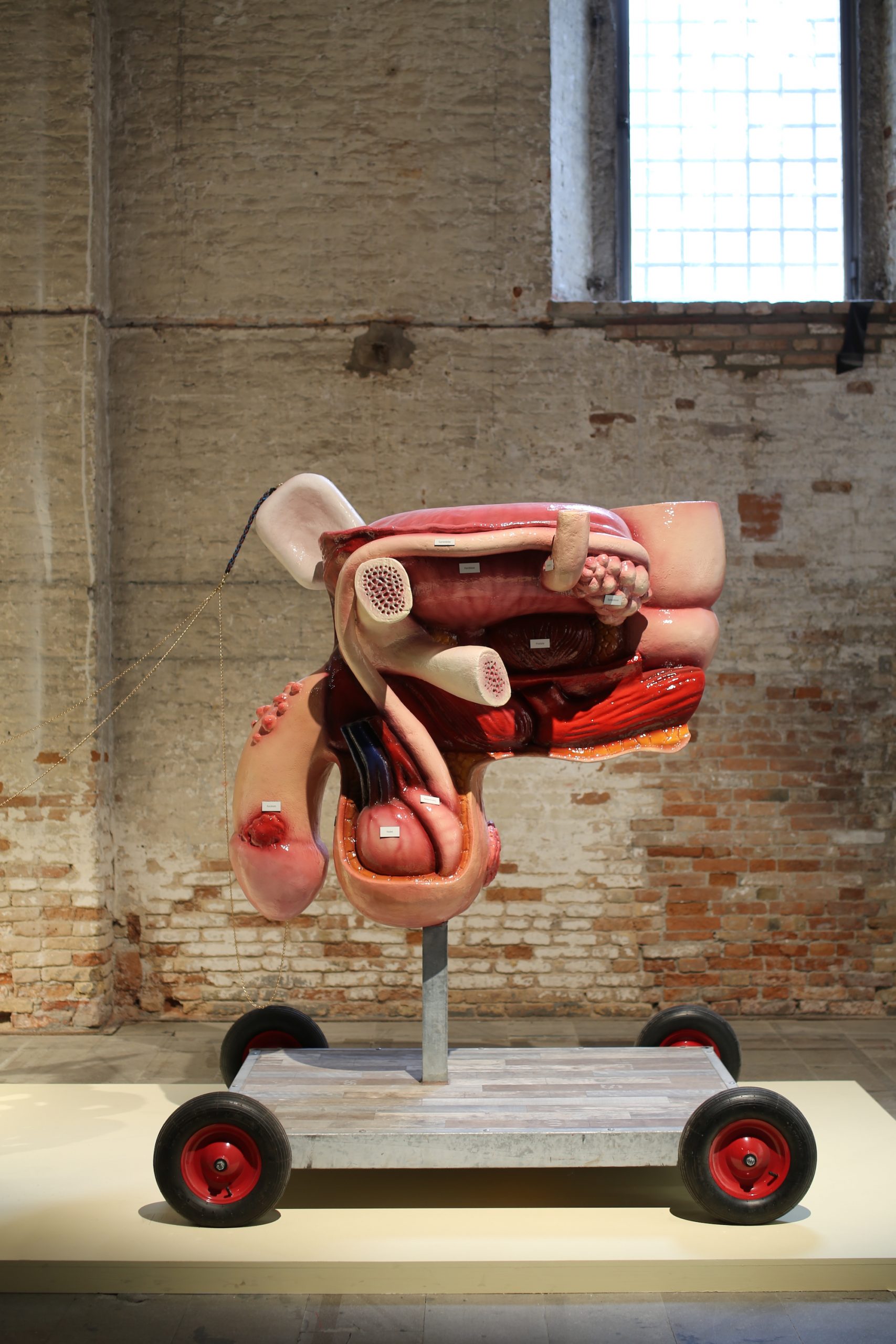

Raphaela Vogel, The Milk of Dreams, 2022, installation view at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Louise Benson

Bodily fluids frame the whole of the life cycle, from the semen of creation to the blood and guts of death. At the Venice Biennale

, fluids leak and drip from exposed body parts and hybrid human forms. In some works, they point to the fragility of the fleshy casings we inhabit. In others, they convey the tactile pleasure of sexuality. They also communicate the violence unleashed on humans and animals by the relentless drive of production and war. Everywhere, fluids spill and pour in the stickiest Biennale yet.

The life cycle begins with Raphaela Vogel’s giant sculpture in the Arsenale: a huge anatomical cross-section of male genitalia acting as a carriage is pulled by a tower of ghostly giraffes, which appear to be formed by energetic sprays of semen. It looks like a pornographic Santa sled.

“Everywhere, fluids spill and pour in the stickiest Biennale yet”

The work is as vulgar as it is comical, and on closer inspection it reveals darker undertones of fleshy diseases and genital conditions: explanatory plates on the anatomical model detail prostate cancer, warts and erectile disfunction. Even in this climactic moment, the destruction of the genitals and their attached body is foretold.

Gloopy fluids are referenced more abstractly throughout the Biennale. Melanie Bonajo’s sex-positive video installation When the Body Says Yes, housed inside the stunning Chiesetta della Misericordia, depicts naked performers writhing in thick, gelatinous liquid. Their bodies glisten in the light like glazed doughnuts, as their rhythmic movements squelch over the soundtrack. It is a celebration of bodies in every form, conveying the pleasure of sensual touch and removing the disgusting connotations often connected with the naked human form and fluids. Like everything else in this work, gloop is shown as viscerally beautiful.

In stark contrast, the horror of body fluids and guts is explored violently by Mire Lee, whose imposing installation makes the most of the Arsenale’s abattoir feel. Endless House: Holes and Drips is straight out of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre school of gore, depicting skeletal forms draped in sinew and flopped across a steely metal frame. Liquid drops from the stretched-out entrails and ceramic bones, splashing into dirty puddles on the floor. This hellish work presents the body in its basest form: sodden meat with no identifiable human characteristics.

Off-site, seasoned painter Anselm Kiefer

also captures the horror of man as meat. His vast painting installation, These writings, when burned, will finally cast a little light, is situated in one of Palazzo Ducale’s magnificently grand rooms, with gilded ceilings and unbelievably ornate painted panels by Tintoretto, Palma il Giovane, and Andrea Vicentino.

“It’s not just human bodies that leak fluids at the Biennale, alien and cyborg forms are also presented as fleshy and perforable”

Kiefer’s thick oil paintings capture the terror of war, with large areas of congealed carmine paint conveying the deep tone of blood en masse, mingled in the dirt from countless fallen bodies. The painting installation is eerily presaged by the Palazzo’s sprawling weapons cabinets in the preceding rooms, displaying all manner of tools humans have invented to puncture one another with.

It’s not just human bodies that leak fluids at the Biennale, alien and cyborg forms are also presented as fleshy and perforable. Andra Ursuta’s sculptures at the entrance of the Giardini’s sprawling space are reminiscent of the gooey creatures that terrorise in Alien and many other sci-fi films. Combining wax casting with 3D printing and often using her own body as a model, Ursuta creates creatures that seem to be skinless, formed in wet-looking lilacs, greens and browns. Not only does their moist surface create the squeamish appearance of bare innards, it also makes the sculptures seem covered in alien goo, with connotations of disease and contamination.

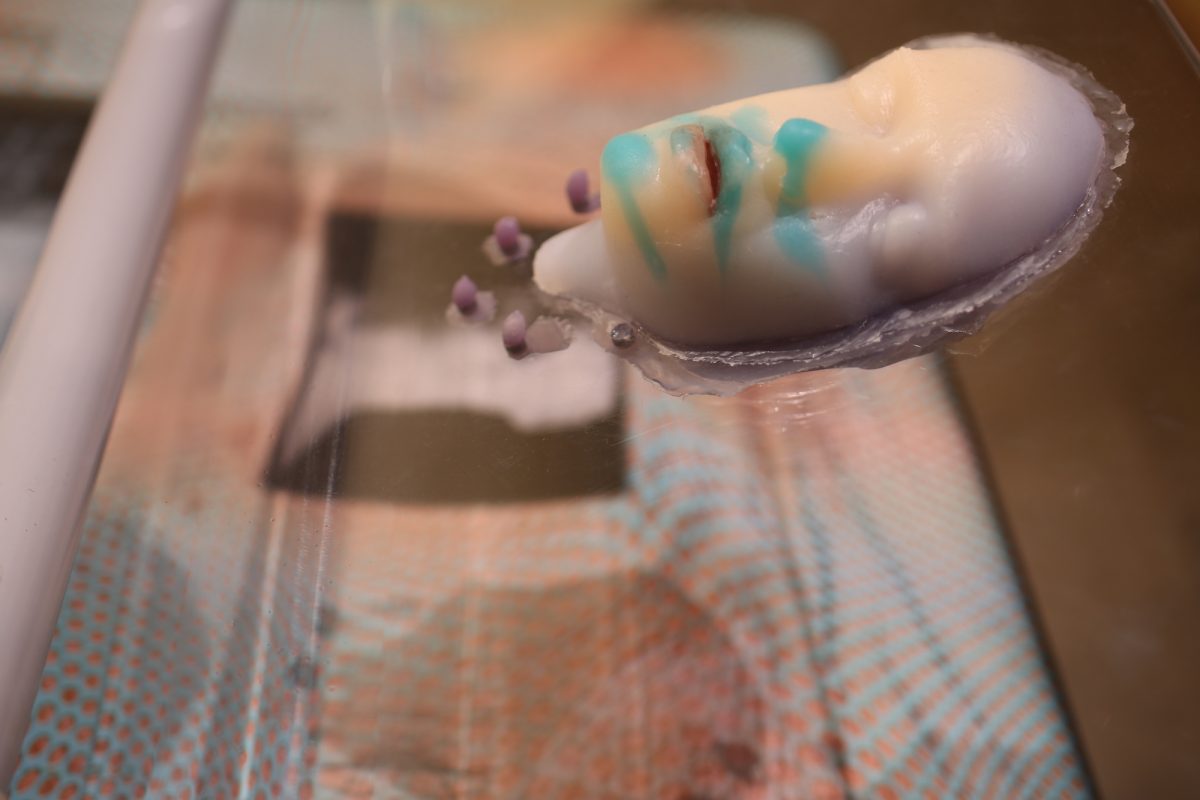

Tishan Hsu’s cyborg-inspired works, shown in the Arsenale, are more comfortably combined with the human world. Silicone and alkyd drip through human-shaped holes in futuristic medical and technological equipment. The body is never whole here, just isolated faces and lumps of flesh, depicted in both naturalistic tones and sugary purples and blues.

- Both: Tishan Hsu, The Milk of Dreams, 2022, Venice Biennale. Photos by Louise Benson

These works explore a mingling of flesh and tech, reflective of a modern world in which the human experience is fed increasingly through man-made forms and technology and less through the physical body. These works show the body in all its wetness as inherently connected with the machines it lives alongside.

“Liquid drops from the stretched-out entrails and ceramic bones, splashing into dirty puddles on the floor”

Jes Fan, meanwhile, works with biological and hormonal fluids almost totally removed from the human form. His glass sculptures are injected with materials including testosterone-laden soap, oestrogen-rich cosmetics and even his mother’s urine. For The Milk of Dreams in the Arsenale, he has created a tiered sculpture from casts of his own body, then covered it in clear globules and drips, based on traditional backflow burners made for incense cones. The work is a nod to Hong Kong’s incense trade, and the industry’s use of a specific resin which is only produced by agarwood trees when they are injured.

As visitors rubbed dollops of sanitiser into their hands and shielded their faces with masks, liquids of all kinds dripped from sculptures and ran down walls, threatening to mingle with everything and everyone around them. The vulnerability of life is an unavoidable topic of this year’s biennale, as recent pandemics and environmental disasters have shown just how fragile the human body is and how inherently connected it is with the world around it.

What clearer way to highlight the messiness of the current climate, than with the sticky substances that spill from human and animal bodies in moments of elation and devastation?

Emily Steer is Elephant’s editor