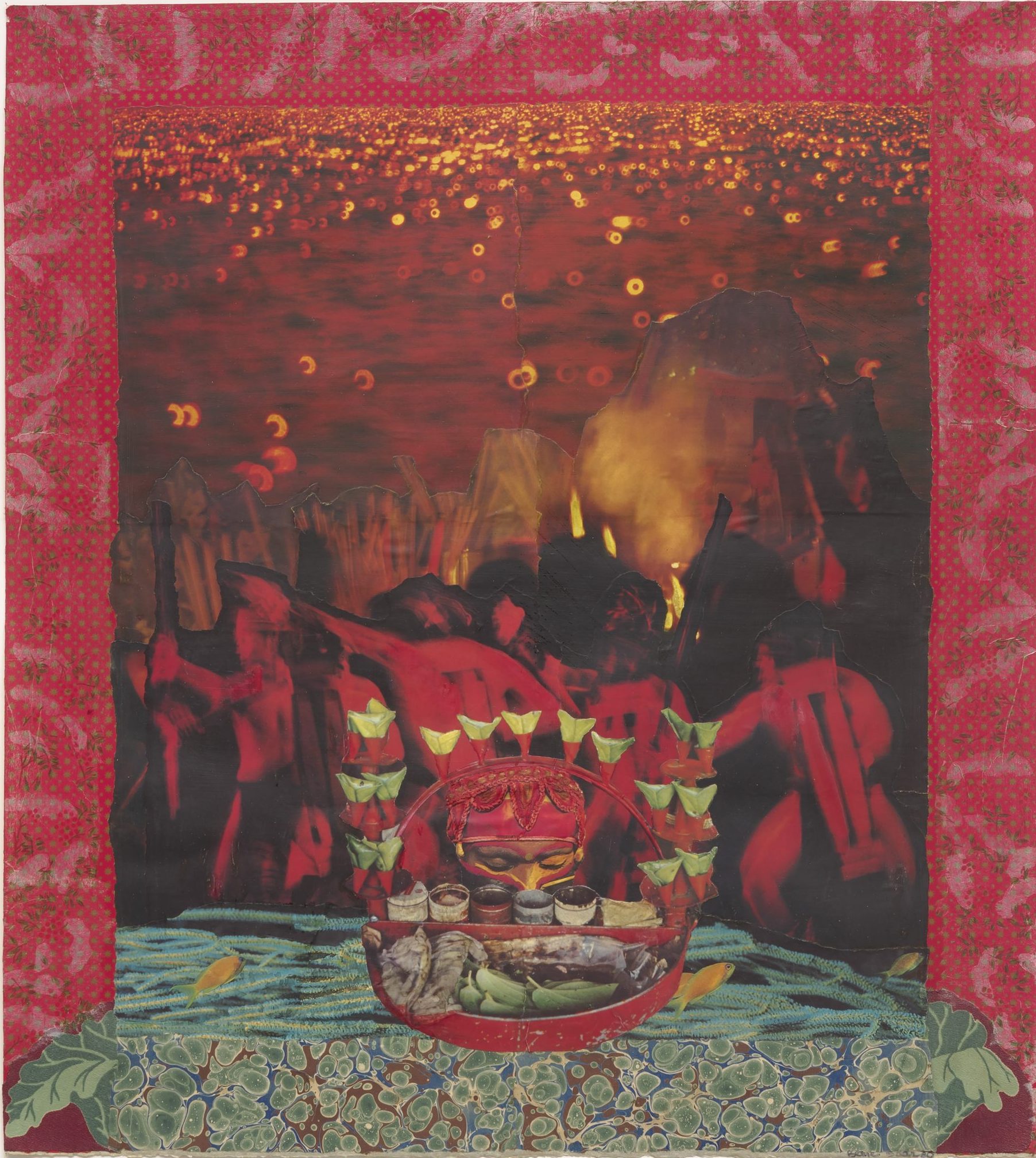

Last year, while chatting with the art historian and broadcaster Katy Hessel on The Great Women Artists podcast, Zimbabwe-born UK-based artist Kudzanai-Violet Hwami described collage as “the language of today”. She went on to say: “It’s a language that came to me. I saw it on Tumblr and how we handle social media. We collage our lives… there are gaps in between that no one is aware of.”

Hwami is one of 16 contemporary female artists whose work is currently on display at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London. Co-curated by Hessel and Texan artist Deborah Roberts, From Near and Far: Collage and Figuration in the Contemporary Age explores the ways in which the act of bringing together various materials on a single surface evokes the world around us.

The show builds on the legacy of leading lights such as Hannah Höch, who in the 1920s used photomontage to protest against contemporary cultural politics, and Pauline Boty, who four decades later incorporated collage into her painting in an attempt to uproot socially constructed roles of women. From Near and Far explores collage as both an art form and as a concept.

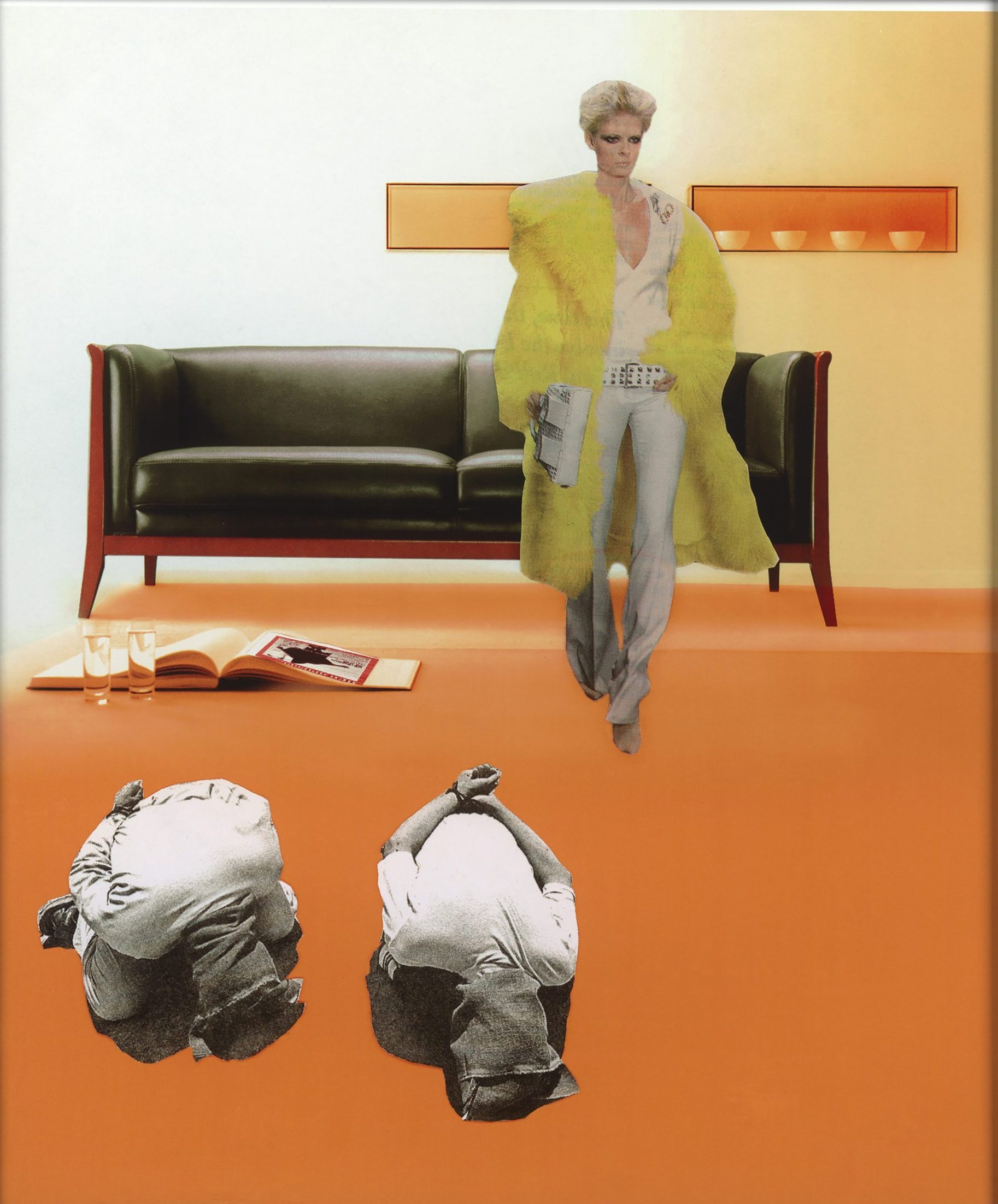

“Collage provokes a melding or uniting of things that conceptually belong together but only in imaginary spaces,” says Martha Rosler, whose best-known photomontage series brought the terror and heartbreak of the Vietnam war into the cosy homes of America. House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967-72) splices together portraits of US soldiers and injured Vietnamese citizens with images of suburban living rooms and breakfast bars. A young amputee hops across a freshly hoovered carpet. In a light and airy lounge, a grief-stricken man cradles the body of a child.

“All photos are fragments, by implication if not by fact, as the camera clearly makes a cut into the visible world,” says Rosler. Another series, The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems (1974-75), comprises 24 panels, each juxtaposing a photograph with a typewritten page. The pictures show shopfronts and façades along the Bowery, a street in lower Manhattan long associated with alcoholism. And yet, the snapshots that appear beside the words (“squiffy snozzled screwed”, “tanked up”, “bleary-eyed”) are free from people. Unlike conventional reportage, Rosler’s montage encourages us to engage with the area rather than simply pinning its problem on one or two subjects.

It was in the 1970s that the American art critic Lucy Lippard made a case for collage ,a medium once dismissed as childlike, being a crucial part of feminist art. In an essay published in ARTnews in 2007, she reflected, “I’ve always been obsessed with the collage aesthetic that defines so much feminist art: a layered, cumulative mode. From Hannah Höch to the Guerrilla Girls to Barbara Kruger to Deborah Bright, collage or montage has always been a particularly effective medium for a political art.”

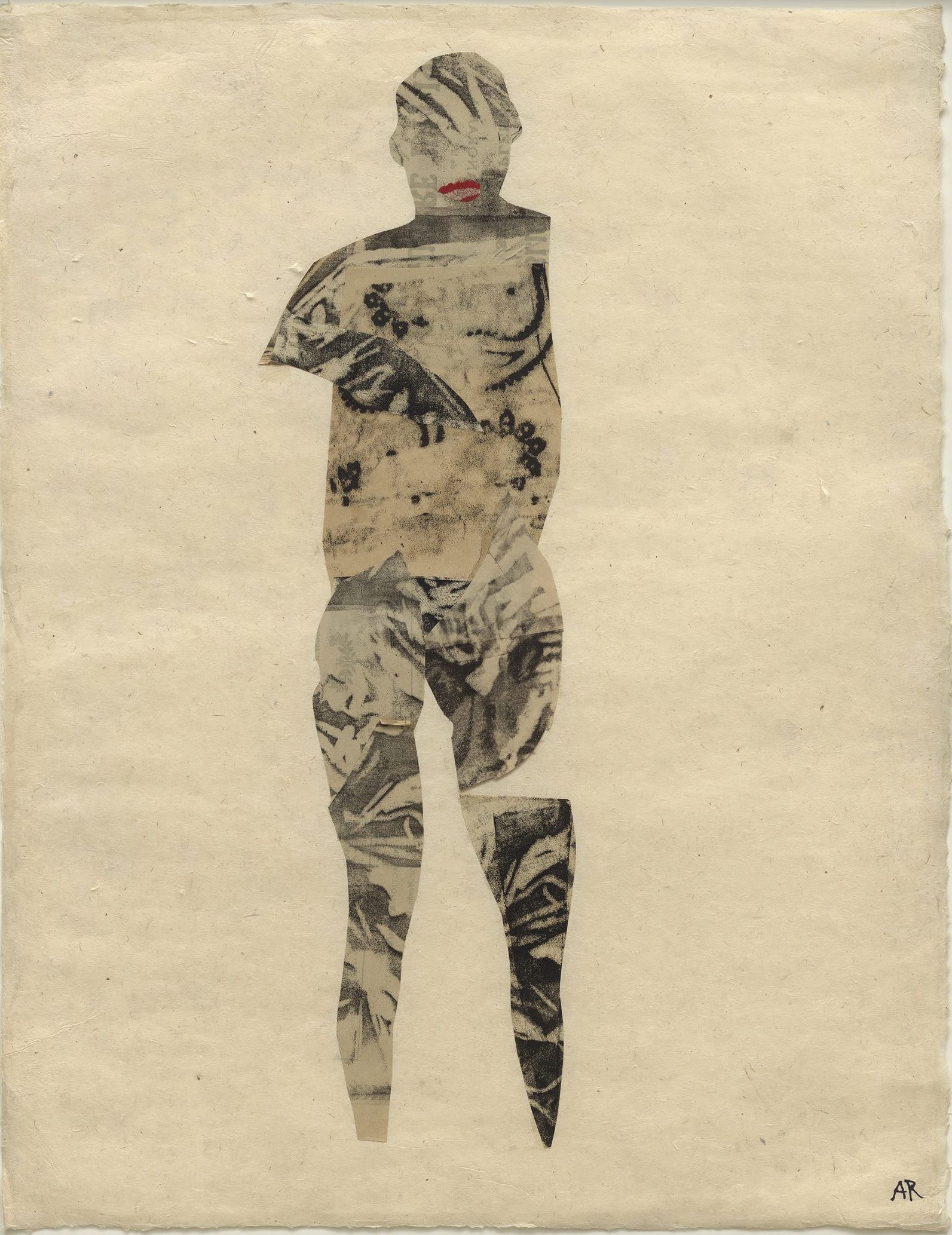

In his review of the Stephen Friedman Gallery show, Waldemar Januszczak writes, “By focusing exclusively on female artists, Roberts and Hessel seem to be saying that collage is a medium that suits women.” But it’s impossible, when considering the history of cutting and pasting together found paper and images from mass media, not to think of the very many men who have done so too: Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Robert Rauschenberg, Kurt Schwitters. “Loathe though I am to champion any male artist over a female artist, I would say that it was discovering the work of Jockum Nordström, married to the great Swedish painter Mamma Andersson, that first got me into collage,” says the British artist Anne Rothenstein.

“When you take images from the world instead of creating them from nothing, as in a painting, there is a logic to them”

For Rothenstein, whose dreamlike paintings feature mysterious figures in pared-back landscapes and interiors, collage was a jumpstart. “I, like so many painters, have an incredibly intense relationship with paint, and there’s something about needing to turn away from it every so often so as not to develop bad habits,” she says. “It’s not that collage is easier (it’s very complex) but it’s different.” In 2012 she’d been experiencing a painter’s equivalent to writer’s block when she received a commission to create a cover for the London Review of Books. “I’d stopped painting, and collage got me going again.”

Rothenstein continued to create collages for the LRB, and since then she’s also enjoyed incorporating the technique into her paintings, which involve a collage-like process of adding and subtracting. Part of Roberts and Hessel’s aim with From Near and Far is to expand the definition of what constitutes collage, and one of the three works Rothenstein presents is a painting. Under a Red Cloud (2022) was inspired by a photograph of pushchairs that Polish women had left on a platform for Ukrainian women and children fleeing the war.

“Collage or montage has always been a particularly effective medium for a political art”

“It started off as a painting of a train station, then the figure of a woman carrying a child became the focus, then the train disappeared, the landscape happened, and other figures emerged,” says the artist. “My paintings rarely end up looking like the image I’ve started with. They go on their own journey.”

A similar journey takes place in Hwami’s thought-provoking paintings, which begin life as digitally edited compositions made up of multiple layers of family photographs and online or nude images. After experimenting with different elements and motifs, she transcribes the finished work onto paper or canvas with brightly coloured oil paint, often incorporating materials and techniques such as pastel and silkscreen. For her, collage is a means of freeing figures from preconceived ideas and assumptions.

Canadian artist Sara Cwynar, who’s currently in residence at Horizon Art Foundation in Los Angeles, also uses digital tools, which she feels allow for a more “surprising and confusing” meshing of images. More broadly, she believes she can do things in collage that wouldn’t make sense in another medium because the source images are rooted in reality: “When you take images from the world instead of creating them from nothing, as in a painting, there is a logic to them, or a way that the viewer doesn’t question their presence as much as if they were invented, and that allows for much stranger and incongruous combinations.”

While Cwynar’s photographic work often starts out as a sculptural construction that’s shot, printed, tiled and re-shot, her videos combine found photographs with those from her personal archive. “Part of the function of collage for me is to make the viewer think twice about all the images they see and absorb daily,” she says. “I want to make images that appear to be one thing but actually aren’t that at all, and for this to lead to a deeper questioning of the things we’re willing to accept within our media.”

“We collage our lives… there are gaps in between that no one is aware of”

Collage, like embroidery and ceramics, may have been relegated to ‘lesser art’ status in the past, but as Rosler points out, occupying a position outside the arts considered ‘highest’ opens a door for experimentation and rule-breaking. “Women may be taking the opportunity to speak truth to power,” she says, “using a medium that lends itself to a subversive noncompliance with accepted, more ‘dignified’, and unified, formats and media such as oil paintings and hard sculptural forms.”

Perhaps, rather than being a medium that suits women, collage is a medium that suits women’s different versions. It takes apart what we are or should be and offers up a newly rearranged reality, free from borders and tidy boxes. It makes space for the apparently unrelatable and inconsistent. It can be beautiful and anarchic, humorous and poignant. It pieces together different cultures, times, places.

“Collage allows for multiplicities,” says Hessel. “It allows for the layering of thoughts and of bodies and of conversations.” And in a world filled with images and captions, what better medium for reflecting that world back to us.

Chloë Ashby is an author and arts journalist. Her first novel, Wet Paint, was published in April 2022

From Near and Far: Collage and Figuration in the Contemporary Age is at Stephen Friedman Gallery until 23 July

Images courtesy the artists and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London