When you arrive in Dubai, it can feel as if you’ve landed on another planet. Reams of colossal skyscrapers compete for attention, as ever-more ridiculous and ostentatious architectural projects rise upward. Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building, channels Middle Earth menace; a pair of imitation Chrysler Buildings contest that two is better than one; and The Dubai Frame (which consists predominantly of negative space) leaves you baffled. Every building seems to operate as its own island, with scrambles of connecting highways delivering individuals from one air-conditioned foyer to another. It is an unsettling experience for someone who spends most of their life getting around by foot or bicycle.

- Courtesy Alserkal Avenue

As the city-state’s self-appointed “cultural quarter” Alserkal Avenue serves as an antidote to the sprawl. The Al Quoz district’s converted warehouses lower your centre of gravity, though by normal standards the structures are still colossal. The buildings are occupied by cutting-edge galleries including The Third Line, Carbon 12 and the Rem Koolhaas-designed Concrete project space, alongside trendy cafés, start-ups, a luxury gym and even an independent cinema. As you wander around in the searing heat, taking refuge among shaded clusters of shabby-chic seating, there is a sense of community, even if it is dominated by wealthy patrons arriving in blacked out SUVs.

“Every building seems to operate as its own island, with scrambles of connecting highways delivering individuals from one air-conditioned foyer to another”

This entire project was founded by Abdelmonem Bin Eisa Alserkal over a decade ago. The Emirati businessman is on the advisory boards of several major global institutions and is enthusiastically engaged with the development of the avenue (which occupies the site of an abandoned marble factory owned by the family) and its programming. “At a time when the majority of the world’s time and money is spent on identifying barriers and boundaries, arts and culture remains one of the few subjects around which we can find commonalities, shared ideas and philosophies,” he explains.

For those of us used to (albeit dwindling) government-funded infrastructure, the notion of an entirely private cultural quarter is a little unnerving, but my enquiries among Dubai residents reveal that traditional models of public funding just aren’t in the country’s DNA. Therefore, efforts like Alserkal are widely celebrated, as they bring a much-needed focus on artistic and cultural enterprise that serves as a counter to the plethora of mega-malls and resort-hotels that serve as tourist destinations.

“At a time when the majority of the world’s time and money is spent on identifying barriers and boundaries, arts and culture remains one of the few subjects around which we can find commonalities”

In fact, the avenue’s latest chapter consolidates a range of philanthropic artistic endeavours. The recently formed Alserkal Arts Foundation formalizes the organization’s network of outreach with a dedicated residency programme, offering studios for up to six individuals, and an exhibiting space, with the proviso that they produce a public engagement programme. Current residents include interdisciplinary artist Željka Blakšić, writer and curator Mahan Moalemi, and experimental duo Metasitu.

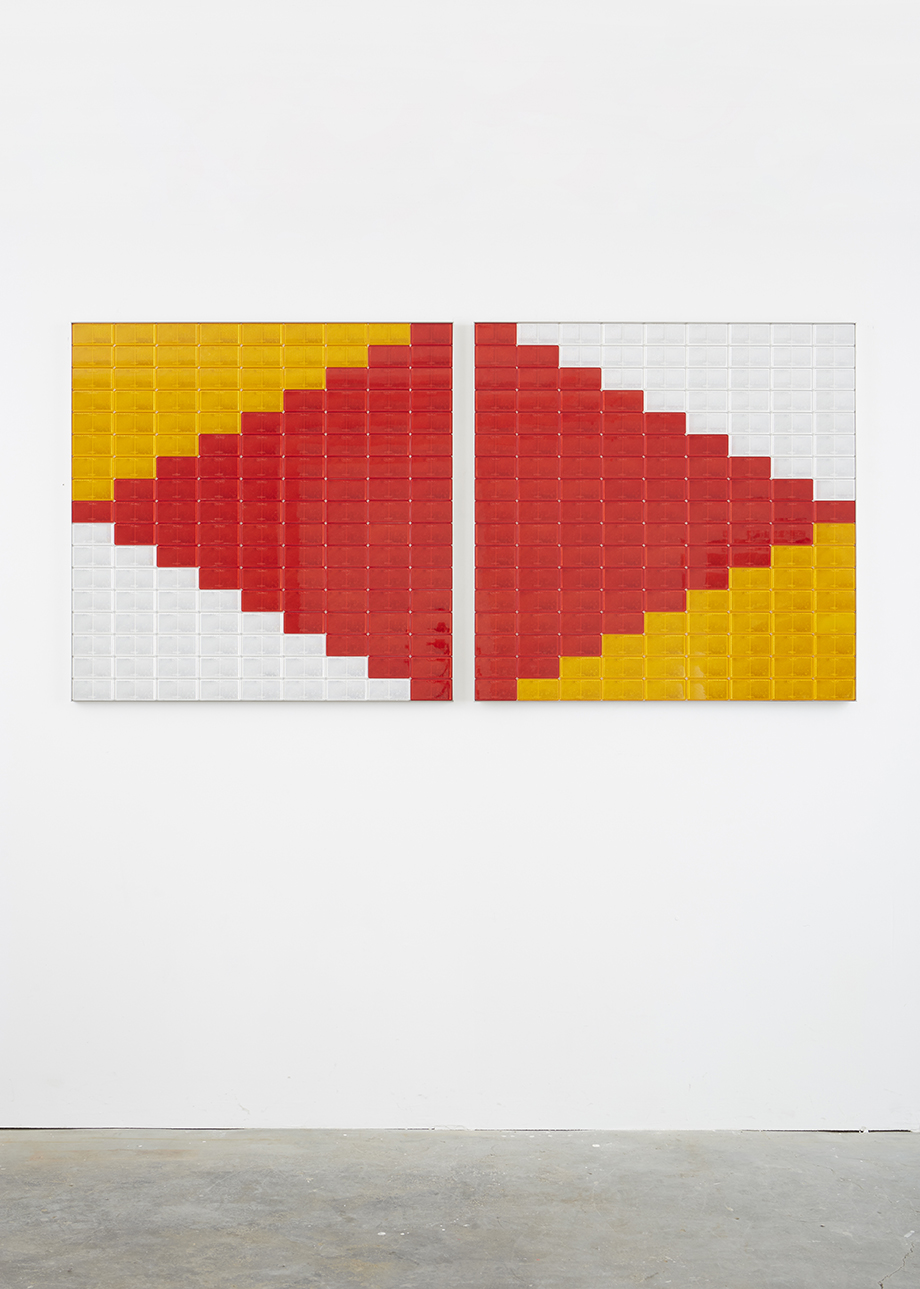

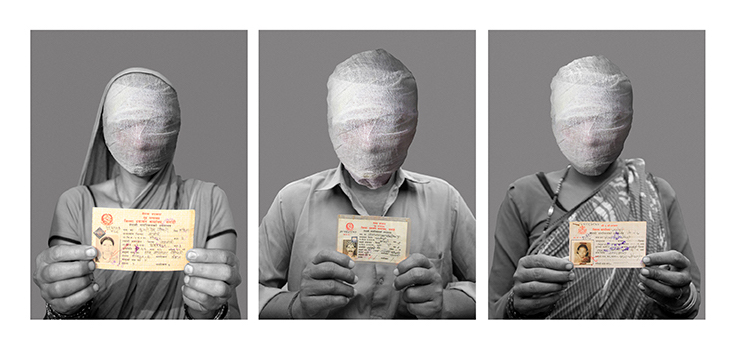

Concrete also served as the venue for the recent Dhaka Art Summit announcement, which is conceived by The Samdani Art Foundation (another private organization with a history of collaborating with Alserkal). The accompanying show Fabric(ated) Fractures brought together fifteen artists from Bangladesh, and considered issues of religious violence, persecution and notions of identity. Although the mammoth performance by Reetu Sattar (which featured a large group of musicians sitting on a scaffold, playing the harmonium) physically dominated, Ashfika Rahman’s emotionally powerful portraits of rape victims who live in the Khagrachari hills area, and Hitman Gurung’s images of masked members of the Tharu community (a Nepalese indigenous group), were shockingly memorable.

One of Alserkal’s newest residents, the Ishara Art Foundation, takes a similarly political line with Altered Inheritance: Home Is a Foreign Place (until 13 July). Once again, this organization is a private not-for-profit, focusing on contemporary art from a South Asian context, and the exhibition brings together work by Sunil Gupta and Zarina, both of whom explore issues of personal identity and geographical displacement. Zarina’s stunning prints study different forms of map-making and wayfinding, tracing the floor plans of her home and reimagining journeys through poetry, while Gupta examines the processes of self-editing undertaken by famous individuals and persecuted communities alike, through a montage of photographic imagery.

It is an impressive show that is indicative of the high calibre of art found at Alserkal, and it proves that even in a country known for murky societal restrictions and ethical codes, confrontational and investigative art can still be celebrated. The community of gallerists, artists and creatives that has sprung up thanks to this development is also a sign that the avenue was sorely needed. Hopefully, it will continue to grow at a pace that promotes real, considered infrastructure—a world away from the glossy enclaves of the skyscraper city.