Art has had a controversial relationship

with the animal kingdom in recent years. This May, the Guggenheim Museum in New York announced that three works featuring live animals were to be withdrawn from its forthcoming exhibition on contemporary Chinese art. The most contentious was a video presenting two pit bulls tethered face to face on treadmills, just out of reach of one another, but spoiling for a fight.

In a similar vein, Algerian artist Adel Abdessemed was forced to remove his video Printemps from an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Lyon, after an outcry on social media. The footage showed a row of understandably distressed chickens hanging by their feet with their feathers on fire—a comment, he said, on the Arab Spring. And while considering some of the more shocking examples in this sub-genre, I can’t help but think of the photographs of Russian artist Oleg Kulik’s time lived as a dog. Before you turn to Google, I have to warn you that they are not for the faint-hearted.

“A massive 83% of the world’s wild mammals have become extinct since the rise of human civilization”

There is nothing shocking in Turner Contemporary’s Animals & Us; no edgy political statements using animals as metaphors and no images of people copulating with dogs (I refer, of course, to Kulik). That is possibly due to the nature of galleries located outside of big cities, which tend to be gentler in tone and broader in appeal—Turner Contemporary has families in mind, after all. If this show was staged at Saatchi Gallery it would be an entirely different beast, but that’s not to say that there aren’t important and timely issues covered here. By coincidence, the Guardian has just published a report detailing some sobering statistics. According to Professor Ron Milo, a massive 83% of the world’s wild mammals have become extinct since the rise of human civilization, and domestic livestock now exceeds the number of wild animals.

Paul Hazelton’s drawings proffer a quiet sadness at the final gasp of an endangered species. The Fading Northern White is a tiny, complex sketch of the last surviving male white rhino, which died in March this year. This intricate drawing is crisscrossed with fine geometric patterns so that you have to lean in and squint to pick out the ailing animal and his attentive keeper. It is a study in fragility, an introspective response to the finality of extinction. From rarity, we move to mass production with Mishka Henner’s large photographs, which he created by digitally stitching together hundreds of images from Google Earth.

From a distance, the result is beautiful and surprisingly painterly, until you look closer and realize that the hundreds of tiny freckles populating these abstract artworks are, in fact, cattle crammed into relatively small pens so that they can quickly gain weight before slaughter. These feedlots in Texas demonstrate the scale of our appetite for meat, and the environmental impact this it has, not to mention the ethical implications of such a practice.

The touring Museum of Nonhumanity, which is introduced here, argues that the rise of agriculture, and the idea that animals are separate from and less important than homo sapiens, paved the way for the oppression of groups within our species; manifesting in the pernicious theories that were put forward to try and justify slavery and ethnic cleansing.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. There are many lighter moments. Noticing that octopuses bring up stones from the seabed when they are pulled out of the water, Japanese artist Shimabuku threw coloured marbles into the sea and speculated what the cephalopods would think of his offerings. “What would be his favourite colour? On the wide reaches of the ocean floor, can a small glass piece connect a man and an octopus?” A sweetly naive drawing depicts a little octopus examining one of these glass trinkets.

Our love of pets is explored here, too. Tracey Emin described the relationship with her cat Docket as a joining of souls, and an intimate bronze sculpture called Docket in My Hand bears witness to her affection. Nearby, hangs Lucian Freud’s etching of his dog. “I’m really interested in people as animals,” he said. “Part of my liking to work from them naked is for that reason… I like people to look as natural and as physically at ease as animals, as Pluto my whippet.” Even JMW Turner, who spent most of his career painting grand, romantic landscapes, occasionally turned his attention to the humble world of donkeys and gun dogs, as evidenced in a tiny book of sketches.

That our bond with pets—and dogs in particular—is so strong is touchingly bourn out in the photographic portraits of Charlotte Dumas, who, in 2011, tracked down the surviving canines that were deployed on 9/11 to search the rubble of the World Trade Center. That these ordinary looking labradors were vehicles of hope and comfort in the aftermath one of the most catastrophic events in recent history is remarkable. These brave pooches, with their benevolent faces and greying muzzles, are captured in their retirement on the front porches of their handlers’ homes, one example of a long history of creatures enlisted in the chaos of human warfare.

We are also offered musings on animal psychology and creativity. Andy Holden & Peter Holden’s enlarged recreation of a bowerbird’s “stage”, an elegant twig structure, which it decorates with carefully arranged coloured objects, prompts us to wonder whether humans are alone in their artistic endeavours, or whether culture is a phenomenon for other species too. And in the same room a video piece by Shimabuku asks whether the snow monkeys of Texas, a group of macaques native to the mountains of Japan, remember their frozen homeland after over forty years living in, and adapting to, a landscape full of cacti and rattlesnakes. The artist leaves a pile of crushed ice on the dusty ground as an aid to jog their memory. It certainly amuses them, but it’s up to us to judge whether the knowledge of colder climes has been passed down the generations.

“The more we learn about the intricate lives of our fellow inhabitants of this varied planet, the more we are moved to protect them”

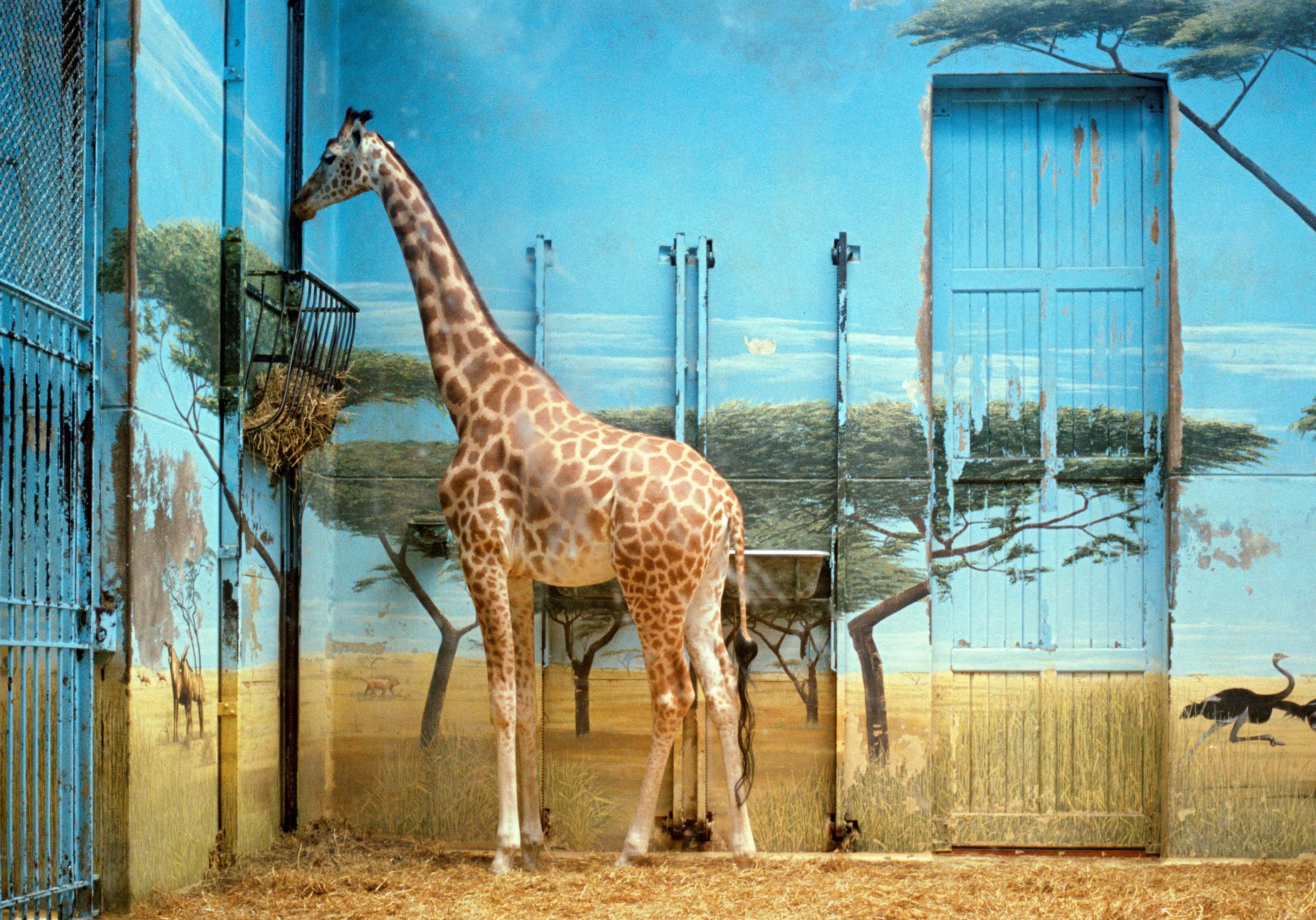

There are many stories here of large and exotic creatures being shipped halfway across the world as gifts. King George IV owned a giraffe, which travelled from Egypt, completing some of his journey tethered to the back of a camel, only to survive a handful of years in its new home. One of Portugal’s kings sent an Indian rhino to the Pope, but it was lost in a storm. With examples such as these, this exhibition reveals more about us, than it does about the rest of the animal kingdom. It is a reminder that our relationship with the natural world is complicated. We are both part of it and apart from it; relentless destroyers and keen observers. We are flawed and greedy, poetic and curious. We are complex in our thinking and we are base in our actions. And it is clear that the more we learn about the intricate lives of our fellow inhabitants of this varied planet, the more we are moved to protect them. And just maybe, as Leonardo da Vinci once said, “The time will come when men such as I will look upon the murder of animals as they now look on the murder of men.”