“It’s so cold, right?” Haegue Yang recalls. “Horizontal rain, very windy. One should in fact wear rubber boots everywhere!” We are discussing the wintry Cornish climate over video link. The artist is at home in Berlin and I’ve just returned to London after seeing her solo exhibition Strange Attractors at Tate St Ives. The gallery sits on the edge of the tourist town, opposite the glorious sands of Porthmeor Beach, which are either beaten by roaring waves or flooded with holidaymakers, depending on the ever-changing weather forecast.

“I am such an urban person, so I am usually quite sealed off from nature,” she adds. “You try and keep the cold and wet out, but there, you just have to let go! You become united with the landscape.” This assault on the senses, and the rhythmic chaos that the elements can unleash, was what convinced Yang to take on the project, having been rather reluctant to begin with.

“Anne Barlow, director of Tate St Ives, convinced me to do a site visit,” she explains. “It was crucial. You feel the harshness of the environment. Aesthetically there is beauty, but physically there is overwhelming power. It is a special mix, plus the mystic sentiment of all the ancient settlements, and their sense of time.”

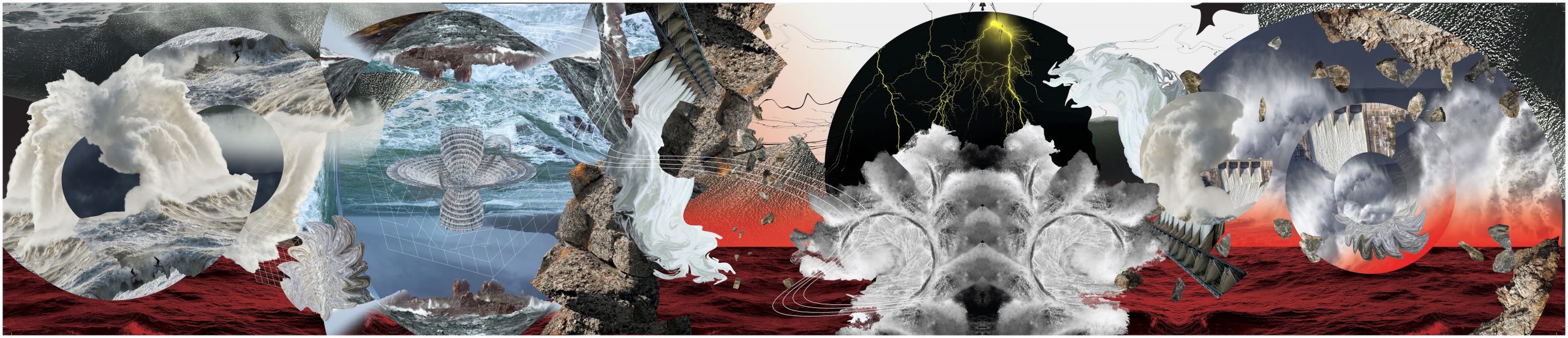

Yang is known for embracing hybridity. She fuses theoretical and scientific concerns with folkloric symbolism, and is just as interested in utilitarian objects and materials as she is in carefully handcrafted processes. These ideas often manifest as enormous multi-sensory installations, bringing together individual elements that function as standalone pieces, as well as forming a carefully choreographed whole. These include wall-spanning digital collages, assemblages formed of lightbulbs and electric cables on drying racks, kinetic structures built from Venetian blinds, and joyous anthropomorphic sculptures that can be ‘activated’ by being pushed or spun manually.

The new sculptural trio conceived for the St Ives show takes the form of strange, seemingly hairy creatures that are in fact made from powder-coated steel frames, and covered in a layer of plastic twine or metal-plated bells. Each piece of Sonic Intermediates – Three Differential Equations represents a different artist who has a connection to the area’s modernist heritage and its relatives: Barbara Hepworth, the British doyenne who lived nearby; Naum Gabo, the Russian constructivist master who was a temporary war refugee in Cornwall; and Li Yuan-chia, the influential Chinese émigré artist and poet, who brought his unique, spiritual and social vision of art to the UK.

“You feel the harshness of the environment. Aesthetically there is beauty, but physically there is overwhelming power”

Thanks to the sculptures’ playful, humanoid appearance, one might not immediately make the connection to the artists who inspired them, particularly as the unusual, textural materials are the first element to pull focus. The longer you look, however, the more these relationships unfold.

The three hollow spheres that form Sonic Intermediate – Parameters and Unknowns after Hepworth (2020) slowly reveal their connection to Hepworth’s Pelagos (1946) with its carefully carved, smooth surfaces, while the meaning behind Sonic Intermediate – Parameters and Unknowns after Li (2020), in which a stout organism clutches a broom, unravels once you realise it mimics a photograph of Li covered in a rug and holding his own brush, which is displayed in the show’s entrance.

“I hope that the exhibition functions without people having any information, but then they get engaged enough to go and find it for themselves”

“I hope that the exhibition functions without people having any information, but then they get engaged enough to go and find that information for themselves,” Yang explains. She is not one for a singular, linear reading, and would rather present different threads and questions that people can engage with on their own terms. “These unknown factors are exactly the idea of Strange Attractors,” she says, referring to the scientific theory that the future is inherently unpredictable due to imperceptible variables. “I am throwing all these things out, so people say, ‘Wait a second… this and this and this… all these things go together?’”

This notion is also connected to Yang’s commitment to fully experiencing the places where she stages exhibitions.

“I am very conscious of that fact, of me being a stranger in most of these exhibiting places,” she explains. “Maybe it comes from being Korean, being from a small country that has suffered so much by frequent foreign invasions, as well as ignorance. I wish to be respectful by making an effort to relate myself to the place and its people. Even in the 1990s it was rather a rare thing for international people to come to exhibit in Korea, so you really appreciated it, but at the same time there was often no dialogue. I always wondered: ‘What is this act of airlifting? Of, boom, appearing and then disappearing?’ That question became seriously relevant to me. I want to be influenced, instead of just superimposing my ideas and then going away.”

“I am very conscious of my being a stranger in these exhibiting places. I wish to be respectful by relating myself to the place and its people”

This has certainly been the case in Cornwall, where not only the inhospitable weather, but the embedded histories of pagan rituals and more localised religious practices had a sizeable impact on Yang. “What we see from a distance is not necessarily the reality of the place,” she notes, alluding to the touristic veneer of the area. During her trip in 2018, she explored not just the obvious cultural circuit but also the community-led St Ives archive, where objects, printed materials and ephemera are curated by senior-citizen volunteers, giving her real insight into the town’s identity.

She also visited the Holy Well of St Madron, guided by Giles Jackson, the exhibition assistant curator. Around 10 miles away, the water at this hallowed enclave is believed to have healing properties. “Usually there will be a standing stone or some kind of architectural evidence,” she says “but here there is nothing. However, there is a strong sense of an intimate and profound place, which differs from institutionalised religion. No one ordained it, it came through a collective, unspoken agreement. It immediately reminded me of Korean animism or shamanism. People simply go to a certain waterfall or rock to release their wishes and lamentations, but no one can tell you exactly why.”

Despite having no urge to experience more traditional religious buildings, she was intrigued by the idea of refuge, which led her to St Senara’s Church in the village of Zennor. “Unlike usual religious institutions, the chapel felt more like a community shelter,” she explains. “Whether it was something for the mind or the physical body, it felt different.”

Rather than being enamoured by the Mermaid Chair, which relates to a famous local folk tale, Yang was intrigued by the idiosyncratic prayer cushions, which featured stitched religious motifs as well as more banal scenes, including a pet dog. She describes discovering “a strange middle ground between religious symbolism and the domestic, personal touch”. This included a stunning vision of an eclipse. “Which is cosmic, right?” she observes. “It certainly goes beyond monotheism. Suddenly there was a whole crack in my reading.” This stitched motif became the catalyst for another new work, Mundus Cushion – Yielding X (2020), which features a replica of the cushion, as well as Yang’s own designs, all displayed on a modular structure inspired by church benches.

To my surprise, she explains that this piece was probably the “most-labour intensive of my entire career”. Such a statement is rather shocking, considering Yang’s exhibitions all over the world have filled some of the greatest museums and art spaces, including the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, the former cargo train station at Documenta 13 in Kassel, and MoMA’s sizeable atrium.

Issues arose because not only was she continually refining the idea for Mundus Cushion by considering conceptions of heaven and earth in parallel with building a portrait of a community, but she also completely underestimated the stitching process, specifically the ability to translate visuals into a form of textile binary code.

“I have to put aside all my know-how, and my mask. I have to start something new. But then it becomes part of my vocabulary and I grow out of it”

“You start to execute the design and realise that the colour doesn’t fit and you have to undo it all,” she says. “Despite the full acknowledgement of labour as an important aspect, I would not have jumped in if I knew how hard it was!”

Despite these protestations, Yang has always shown a deep reverence for craftsmanship, particularly traditional methods, even if she subtly subverts their legacy by utilising synthetic, mass-produced materials. This is seen clearly in her first macramé sculpture, Floating Knowledge and Growing Craft – Silent Architecture Under Construction (2013), or in the intricate synthetic-straw weaving of The Intermediates series (2015–ongoing).

This strange blend of old and new can be joyously jarring, not least because these methods and materials often form part of unusual alien-like structures. The hunt to decode, to unpick textures, patterns and reference points, encourages the viewer to truly engage with what is right in front of them. It is very hard not to reach out and touch.

“It is all about honouring tradition,” she affirms, “especially as craftsmanship such as stitching used to be practised largely by the woman. Whether there was any consciousness or outside recognition, these women were trained designers, who knew how to send out aesthetic signals through their work, which often led to unanticipated masterpieces.”

Yang’s approach toward skills and knowledge is uplifting. She describes feeling clumsy when learning about a new technique or location. “I have to put aside all my know-how, and my mask. I have to start something new,” she explains. “But then it becomes part of my vocabulary and I grow out of it. There are so many stories. It is beautiful.”

Holly Black is Elephant’s managing editor

This article appeared in Elephant #46 — Autumn/Winter 2021, available to buy here