While it goes without saying that the worlds of art and music are longtime passionate bedfellows, until fairly recently disco as both a genre and as a physical space have been somewhat sidelined in the canon. Perhaps that’s down to snobbish notions of “good taste”—something the high camp, sequins and general very-good-fun that embodies the sound of disco shrugs right off. Perhaps it’s because disco goes in and out of fashion—and has been more often out than in—for much of the late twentieth century.

Yet there’s a lot to be said for disco as a four-to-the-floor driver of some superb contemporary art; and as our music editor Arwa Haider pointed out in her discussion of Nile Rogers-curated Southbank’s Meltdown festival: “The disco era transformed nightlife into an art form; the hottest venues flaunted visionary designs, and the dancefloor became a place of unity, identity (and aspiration) and joyous hedonism”.

Studio 54, of course—disco’s most renowned site for the nascent genre in the 1970s—is known for having ushered in art world superstars like Andy Warhol, who celebrated his fiftieth birthday there. But the seventies, with all its glitter balls and platforms and seemingly endless cocaine, is far from the peak of art’s relationship with disco—a genre that was endlessly innovative and progressive, despite what its critics may have dismissed it as. Disco music is smart music: it’s democratic, sprawling in its ongoing influence, and frequently manages that nigh-on impossible task of merging joyful abandon with a sense of poignancy and defiance against prejudice (its early proponents, of course, were mostly non-white, and delivered by female vocalists.)

“Disco music is smart music: it’s democratic and sprawling in its ongoing influence”

The backlash against disco in the late 1970s, the Disco Sucks! campaign, only served to underscore the brilliance of such defiance, and demonstrated disco’s capacity to spawn great art. Launched by Detroit rock radio DJ Steve Dahl as a response to the likes of the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin losing out in terms of airplay to acts such as Chic and Donna Summer, he called out for listeners to call in disco song requests before “destroying” the tracks on air “with explosive sound effects,” as The Guardian journalist Ben Myers put it. At the heart of the campaign were some pretty obviously nasty racist, homophobic and misogynistic prejudices.

Dahl’s daft and rather childish response to the genre (aww, poor thing, no Zep!) caught on, with guitarist Steve Veek (whose father owned the Chicago White Sox baseball grounds) helping the DJ offer cheap entry to the team’s next home game if they brought along a disco record, which would duly be destroyed. It proved a success of sorts, with 59,000 people showing up to burn disco vinyl as they sported t-shirts professing their love of Black Sabbath and the like. There’s nothing wrong with rock music—far from it—but, as Myers says, “the unspoken subtext was obvious: disco music was for homosexuals and black people”

Ultimately, the movement proved the true art underpinning disco: with its commercial tendencies and the snarling from the likes of Dahl, the genre went back to its underground roots and informed everything from Italo to synth pop, no wave and new wave—a genre led mainly by art school types with more cerebral tendencies like Talking Heads, Rhode Island School of Design grads who made a mockery of the Disco Sucks! movement. In 1979, the band released the album Fear of Music, with its most famous track, Life During Wartime, making a subtle jibe to the disco-haters (“this ain’t no party! this ain’t no disco!”) through exactly the sort of driving funk and repetition that forms disco’s foundations.

In the decades since disco’s emergence, we’ve seen it crop up again and again in art. This year’s Fierce Festival of performance art in Birmingham will see choreographer Marco Berrettini, a student of Pina Bausch and 1979 German disco-dancing champion when he was just fifteen, present his piece iFeel2. Billed as “an elegant and repetitive dance in a tropical dream-world”, the piece is based around two topless dancers, a man and woman, encircling one another with slowed down disco-like movements—that hip-rolling, shoulders back-and-forth sort of action—but set against ethereal sounds led by a trance-inducing female voice. The piece is said to be inspired by German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk’s book You Must Change Your Life, and address the question “Why are we here, on this earth?” Big ideas, but then, that’s what disco can do.

Disco’s impact on music is perhaps most pertinent in rave and house; and as such, it makes sense that it’s at the fore of several works created during the YBA’s heyday. One example is Tracey Emin’s 1995 piece Why I Never Became a Dancer. The six-minute video narrates her early teenage years—her sexual escapades, her days wandering Margate’s seafront and coffee shops, drinking cider, post-pub fish and chips before sex—using collaged imagery of the Kiss Me Quick hat-style English coast town and its arcades that seem quaint but somehow sinister. The denouement comes as Emin says “By the time I was fifteen I’d stopped shagging, but I was still flesh and I thought with my body, but now it was different, now it was me and dancing—that’s where I got my real kick—on the dancefloor. It felt like I could defy gravity, as though my soul were truly free.”

Our hearts soar for her during the tale of the local finals of the disco dancing championships—the audience claps and cheers, she thought she might win—only to be crushed again as we hear how during her performance, the same older men who took advantage of her body, those in their mid-twenties who fucked her in alleyways when she was just fourteen, start chanting “Slag, slag, slag.” The final fuck-you to those men, of course, is the piece itself—Emin in 1995 is an artist, smiling and swirling around a room, just her and a boombox blaring out Sylvester’s defiant, joyful disco belter, You Make Me Feel Mighty Real.

Emin’s peer Gillian Wearing’s Dancing in Peckham, a 1994 video piece, also reveals a love of disco. While the piece is silent, and shows Wearing dancing, alone, apparently to no music at all in a south London shopping centre, Wearing has said that she practised for the piece listening to disco legend Gloria Gaynor. Wearing and Emin alike prove disco to be more than sparkly, cheesy, hedonistic nonsense: it’s an inspiration to carry on in the face of adversity; a boost; a triumph in sonic form.

“Wearing and Emin alike prove disco to be more than sparkly, cheesy, hedonistic nonsense: it’s an inspiration to carry on in the face of adversity; a boost; a triumph in sonic form”

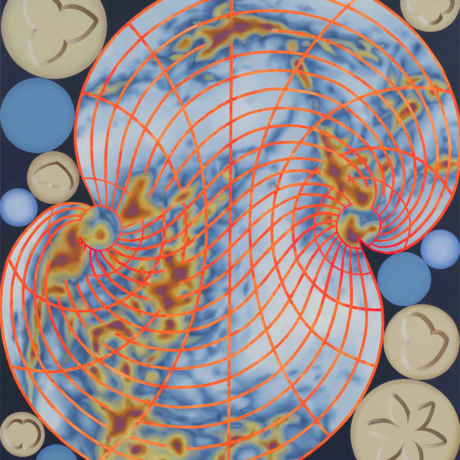

In the years since, disco’s influence on contemporary art is as palpable as ever. Sometimes this is manifested in more abstract ways, as in the case of Gordon Lee’s 2012 painting, Disco Shrine, a strange still-life featuring a coffee pot and buddha, among other objects, within a glistening tiled electric blue wall. A show opening this month of US-based artist Tony Cokes titled If UR Reading This It’s 2 Late: Vol I at Goldsmiths CCA gallery also references disco as part of the artist’s wider examinations of music in his video art, which unites Malcolm X, David Bowie, Donald Trump, “the Bush administration’s use of colour to engender a perpetual culture of fear” and how music was “used to torture detainees during the so-called ‘war on terror’”.

Elsewhere, disco emerges in the genres it helped spawn, such as rave, as in Mark Leckey’s 1999 film Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore. Nightlife culture, of which disco was an early bastion, is now an accepted part of the art world landscape, with numerous exhibition and museum shows dedicated to it in recent years. The impact of disco is not to be underestimated: take it seriously, but not too seriously—disco, after all, is perhaps the most pure manifestation of joy and defiance you can possibly hear.

Listen to Emily Gosling’s Disco Dancing playlist on Spotify now