“Police brutality must go”. Emblazoned on a protest placard in New York in 1963, and photographed by Gordon Parks, this statement feels as relevant as ever today. More than fifty years on, little has changed. The brutal murder of George Floyd—an unarmed, handcuffed African American man—by white police officers in Minneapolis last week has led to mass protests across the United States and beyond. This was not an isolated incident. For black lives to be protected, and their voices to be heard and upheld, the systemic injustice and institutionalised racism that remains embedded in our society must change.

During protests against the violent politics and painful hypocrisy from those in power, artworks and artist films can provide guidance and support. They also offer an opportunity for reflection. From Martine Syms’ extended poem in 180 parts about the black radical tradition to John Akomfrah’s charged portrait of cultural theorist Stuart Hall, these ten artworks are necessary viewing.

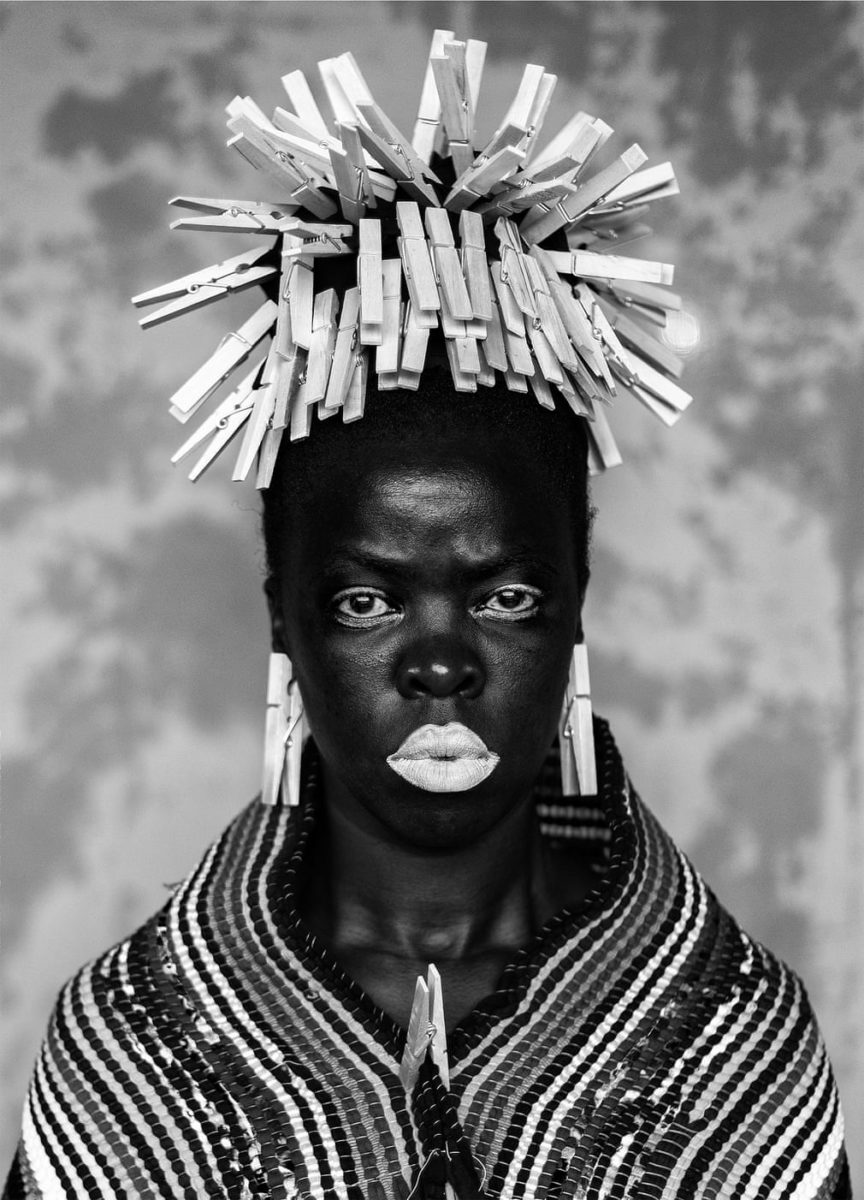

- Left: Zanele Muholi, Bester I, Mayotte 2015. Right: Zanele Muholi, Ntozakhe II, Parktown 2016. Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York © Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi, Faces and Phases (2006)

Zanele Muholi is a South African visual activist and photographer. For over a decade they have documented black lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people’s lives in various townships in South Africa. In Somnyama Ngonyama (“Hail the Dark Lioness” in Zulu), they turn the camera on their own face, adopting different poses, characters and archetypes to address issues of race and representation. From scouring pads and latex gloves to rubber tires and cable ties, everyday materials are transformed into politically loaded props and costumes. The resulting images explore themes of labour, racism, Eurocentrism and sexual politics. The Tate Modern was due to showcase Muholi’s first solo institutional exhibition in the UK from this April to October 2020, until the gallery was closed due to Covid-related restrictions.

Arthur Jafa, Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016)

Arthur Jafa’s extraordinary seven-minute film brings together YouTube footage, hip hop videos, CNN replays, dash-cams, basketball games and home movies. Combined, they give a visual vocabulary to black American experience. There is footage of black people dancing; icons such as Malcolm X and Michael Jackson; Obama singing “Amazing Grace”. Importantly, it also includes clips of the police brutality that has exposed the wounds of structural racism: the 1991 Rodney King tape and images from the 2014 protests in Ferguson, Missouri. Stitching together images on one visual plane, Jafa puts hope and despair in dialogue, suggesting that both are necessary components of black America.

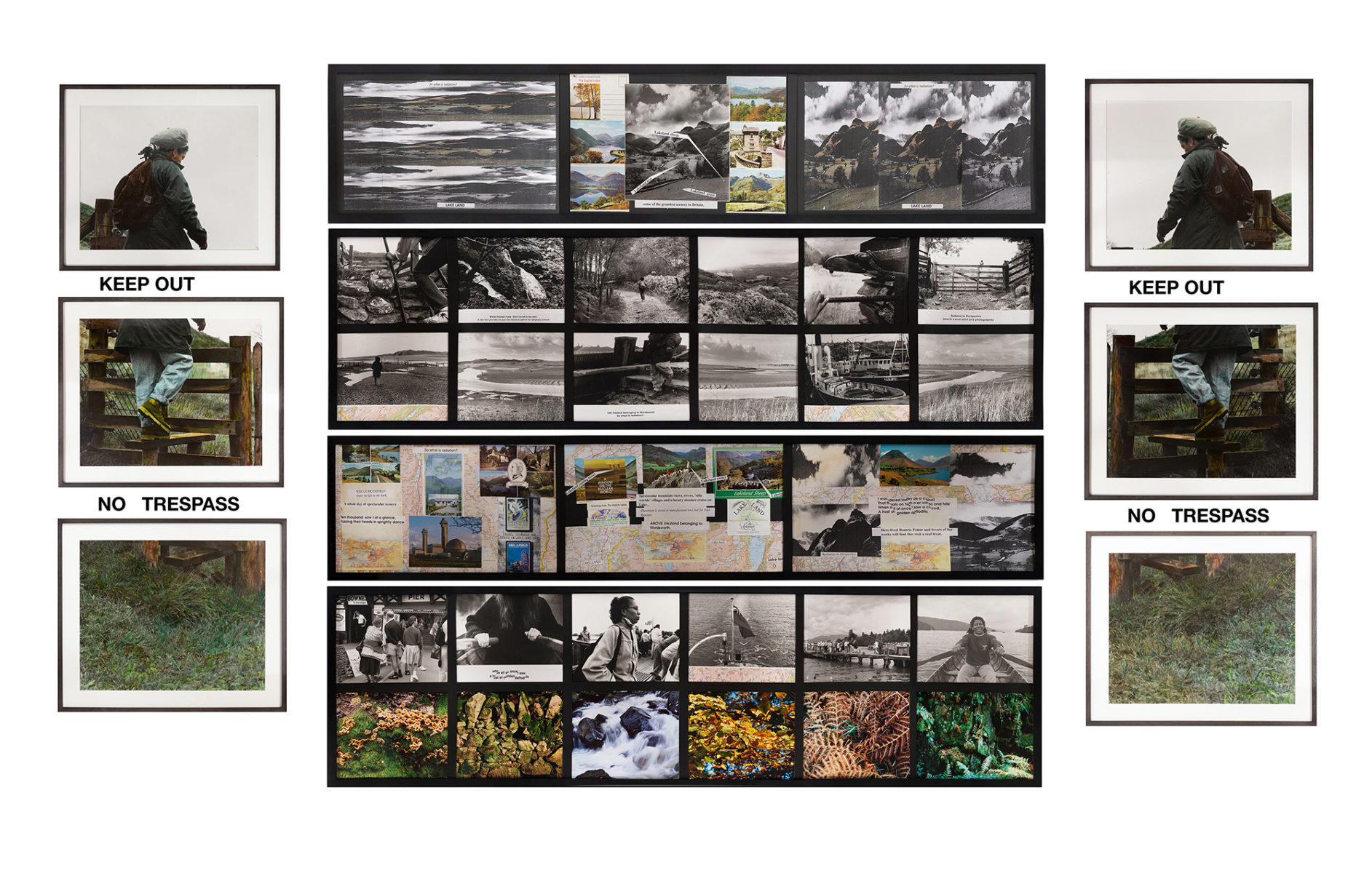

Ingrid Pollard, The Cost of the English Landscape (1989)

Ingrid Pollard has worked in the UK as an artist and photographer since the 1980s, when she was part of a group of British artists who championed black creative practice. She has an ongoing interest in the English landscape and coastline, raising politically charged questions in her work about the hidden histories of the rural and its colonial relationship to Africa and the Caribbean. She questions the social constructs of Britishness, as well as the notion of home and belonging. “I still hear complaints from black students that they are the only one,” she reflected in an interview with Elephant earlier this year. “You just have to look at the teachers and professors—the black percentage is very small.”

![Martine Syms, Lessons I-XXX [film still] 2014. Copyright Martine Syms, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London](https://elephant.art/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Lessons_I-XXX_2014_006_canonical.jpeg)

Martine Syms, Lessons I-CLXXX (2014–2018)

Martine Syms uses video and performance to examine representations of blackness. Lessons I‒CLXXX is an ongoing, incomplete video work composed of thirty-second clips; a cumulative poem whose structure evolves at random. Snapshots of disconnected experiences and subjects accumulate into a mass of fragmentary narratives, relating (directly and incidentally) to the lives of black Americans. Drawn from myriad sources—including YouTube videos, 1980s TV shows, Vines and personal footage—it is a growing body of work. She also runs Dominica Publishing, an imprint dedicated to exploring blackness in visual culture.

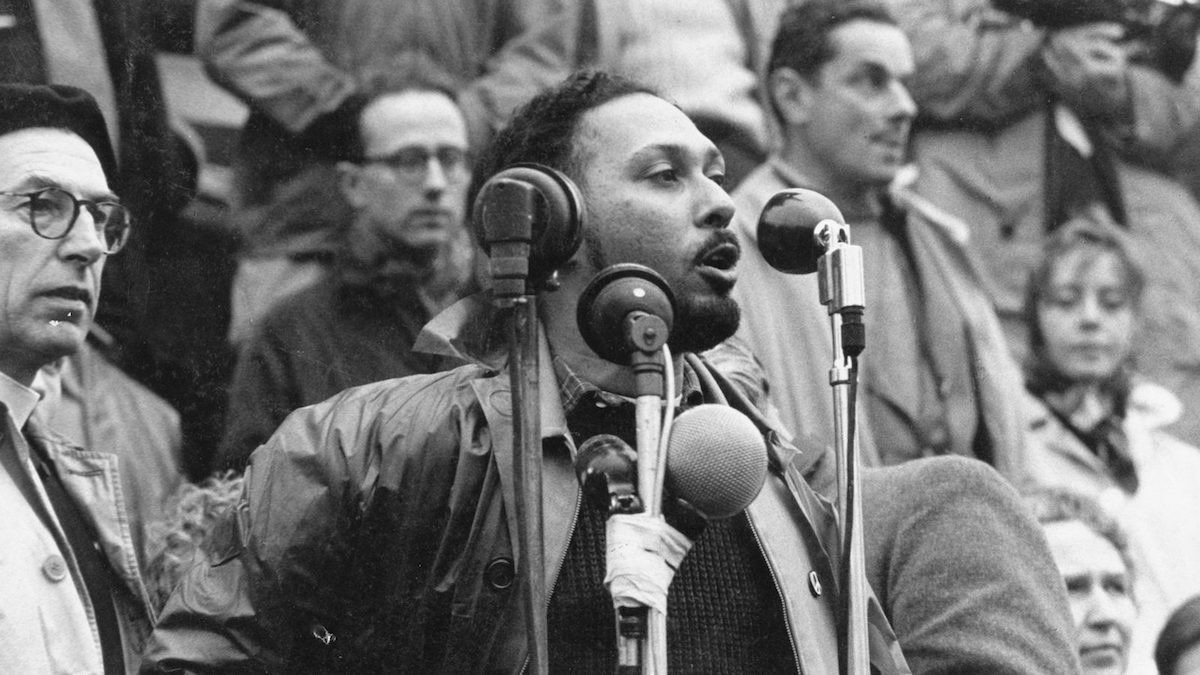

John Akomfrah, The Stuart Hall Project (2013)

This is an intimate and remarkable portrait of Stuart Hall, edited together from over 800 hours of archive footage. Hall was a Jamaica-born pubic intellectual and co-founder of the New Left Review, whose work in cultural studies profoundly influenced the political and academic landscape. Akomfrah has long worked with archival footage to bring overlooked histories and untold stories into the light. In The Stuart Hall Project, he weaves between the musical archeology of Miles Davis and the political narratives of the twentieth century, charting the upheavals and turning points of worldwide political and cultural change. The film is available to watch on BFI Player in the UK.

- m.A.A.d, 2014

Motion picture stills

Kahlil Joseph, m.A.A.d. (2014)

Kahlil Joseph‘s poetic, dreamlike film m.A.A.d. is made up of fragments of found footage and home videos, alongside cut-up news footage of police brutality and material shot by Joseph in Compton and Los Angeles. He weaves together the threads of black history in an emotional, continually surprising 360-degree portrait. His rhythmic editing carves new meaning and nuance out of disparate, sometimes painful scenes. In an interview with Elephant in 2018, he asked, “What individual is not conscious of their race as soon as they’re born, just like one’s gender?”

View this post on Instagram

Deana Lawson, Binky & Tony Forever (2009)

Deana Lawson is a photo-based artist whose work examines the body’s ability to channel personal and social histories, addressing themes of familial legacy, community, romance, and spiritual aesthetics. Her work draws upon various visual legacies, from photographic and figurative portraiture, social documentary aesthetics, and vernacular family album photographs. Lawson is visually inspired by the intimate materiality of black culture and its expression, as seen through the body and the home. “Outside a Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling,” Zadie Smith wrote in The New Yorker in 2018. “But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

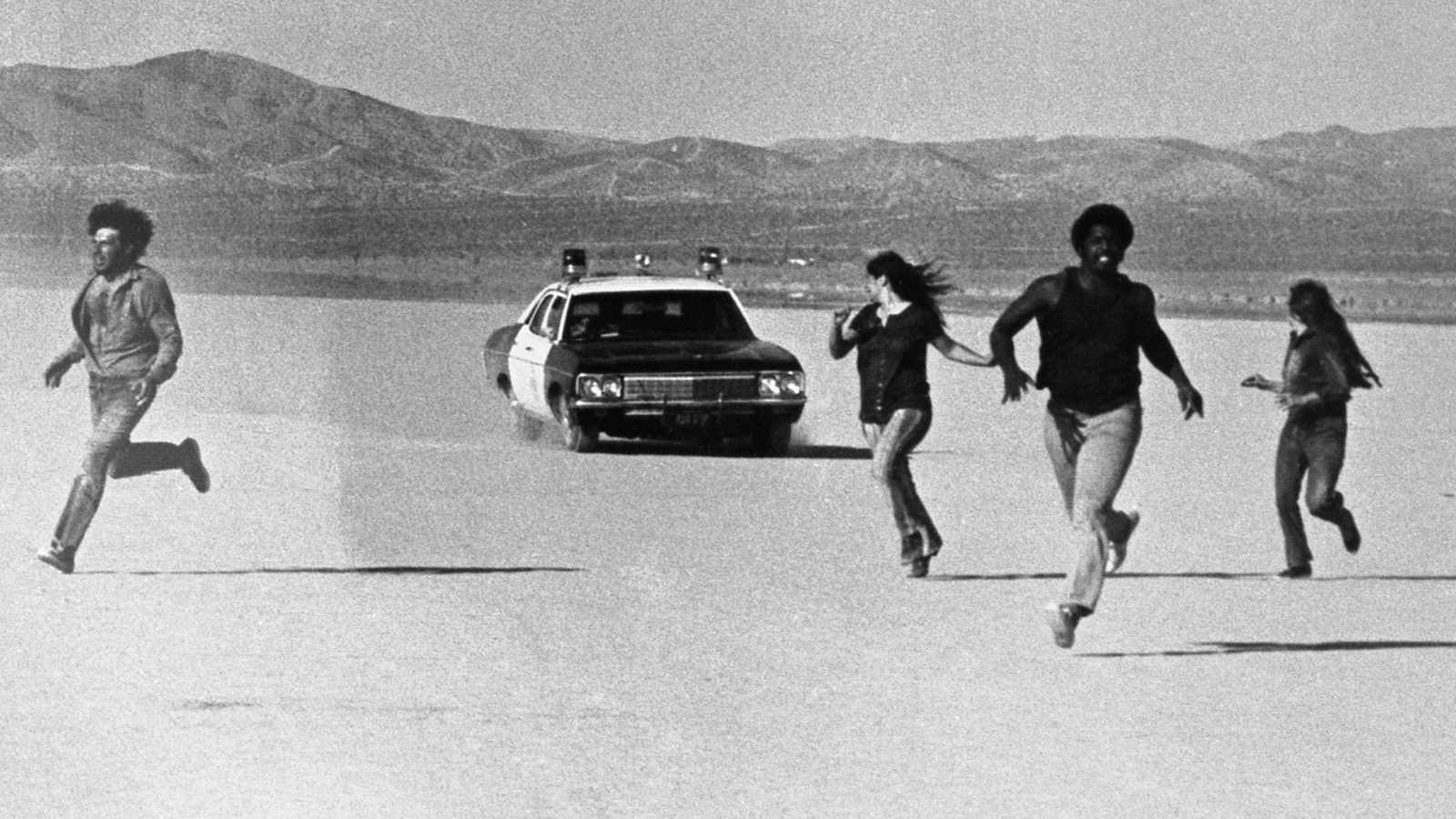

Peter Watkins, Punishment Park (1971)

Punishment Park, a dystopian horror film focused on radicals being hunted down by the state, remains as disturbing as ever. A group of anti-war activists are unlawfully detained in a desert zone, and must make the impossible decision between indefinite detention or a fatal “game” of escape from the titular Punishment Park. Pursued by law enforcement officers, they must reach the American flag posted fifty-three miles away across the mountains, within three days. Presented as a pseudo-documentary, the results feel uncannily real at a time when mass arrests, tear gas and rubber bullets are being used at protests across the United States and in the UK. The film is available to watch on Amazon Prime.

Larry Achiampong and David Blandy, Finding Fanon Trilogy (2015)

The Finding Fanon Trilogy is inspired by the lost plays of Frantz Fanon, (1925-1961), a politically radical humanist whose practice dealt with the social and cultural consequences of decolonisation. Across three films, Achiampong and Blandy negotiate Fanon’s ideas, examining the politics of race, racism and the post-colonial, and how these societal issues affect their relationship. Achiampong reflected on racism in the UK during an interview in 2017 with Elephant: “If we can’t dream or hope for our kids, there’s almost no point to any of this. But it becomes equally tough when your son comes home and says, ‘I don’t like the brownness of my skin.’ […] You can’t separate the personal from the professional or the professional from the political.” The trilogy is available to watch on Vimeo.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Dark Room Mirror (2017)

Paul Mpagi Sepuya‘s work is suspended between self-portraiture, the camera and homoerotic visual culture. He negotiates a new place in art history for the male nude body in the constructed studio space. In an interview with Elephant last year he stated, “I am a black man, and I am ever conscious of my proximity to women, especially white women, as I walk the street as a pedestrian. I am conscious of moving in white spaces, and how well I do or do not fit into black spaces.” During the current protests, Sepuya has announced that he will personally donate a print to anyone who provides receipt for a donation of $250 and upwards to organisations such as National Bail Out and #BlackLivesMatter-Los Angeles.