Is having kids the end of a woman’s career in the arts? Sometimes it seems so. From Sheila Heti’s novel Motherhood to Elena Ferrante’s The Lost Daughter (and Maggie Gyllenhaal’s 2021 film adaption), contemporary culture teems with examples which pit having kids against creative aspirations.

Becoming a parent can affect artists’ careers, especially if the artist in question is a woman, as illustrated by art critic Hettie Judah in 2020. Writing an essay for a Freelands Foundation survey on the representation of women in British art, Judah interviewed 50 artist mothers and discovered some hard home truths.

“The impact of motherhood can be felt as soon as an artist knows she is pregnant,” she wrote. “One pregnant artist had performances cancelled without consultation. Another experienced tension with a gallerist who did not approve of her decision to start a family. Others report work drying up, and diminishing communication from institutions, galleries and funding bodies. It is therefore hardly surprising that many artists worry they might lose work…”

In 2021 Judah published a set of guidelines for cultural institutions titled How Not to Exclude Artist Parents, in which she laid out some practical considerations. “Consider options such as weekend daytime private views rather than sticking rigidly to early evenings when children need to be fed, bathed and put to bed,” states one pointer. “It shouldn’t be left to the artist to have to ‘confess’ to being a parent, or to fear they may lose a show, commission or residency if they do so,” reads another.

“The impact of motherhood can be felt as soon as an artist knows she is pregnant. One pregnant artist had performances cancelled without consultation”

Another tip suggests allowing artists to invoice separately for the portion of their fee they will need to spend on childcare as a direct cost, so it isn’t taxed as income. It is a pressing concern when, according to a recent survey by the Pregnant Then Screwed charity and Mumsnet, two thirds of UK respondents pay as much or more for childcare than for housing.

The right to remain child-free, or express ambivalence about parenthood are important of course, but if artist mothers are never celebrated it will be difficult to shift “the enduring cliché that a woman cannot be both”, as Judah puts it. And that goes for fathers too, because while it continues to seem almost impossible to reconcile kids and work, men will often stay stuck as the breadwinners of the family.

Perhaps what we need is a completely new mindset, one which puts children centre-stage rather than hiding them away? American writer Maggie Nelson drew on her family life for her celebrated 2015 book The Argonauts. Photographers such as Sally Mann and Christopher Anderson have built up important bodies of work featuring their kids, showing them publicly in books and galleries. In 2013 curator Susan Bright framed a whole exhibition around having children (or not) titled Home Truths: Photography and Motherhood, which travelled from The Photographers’ Gallery and Foundling Museum in London to Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Photography.

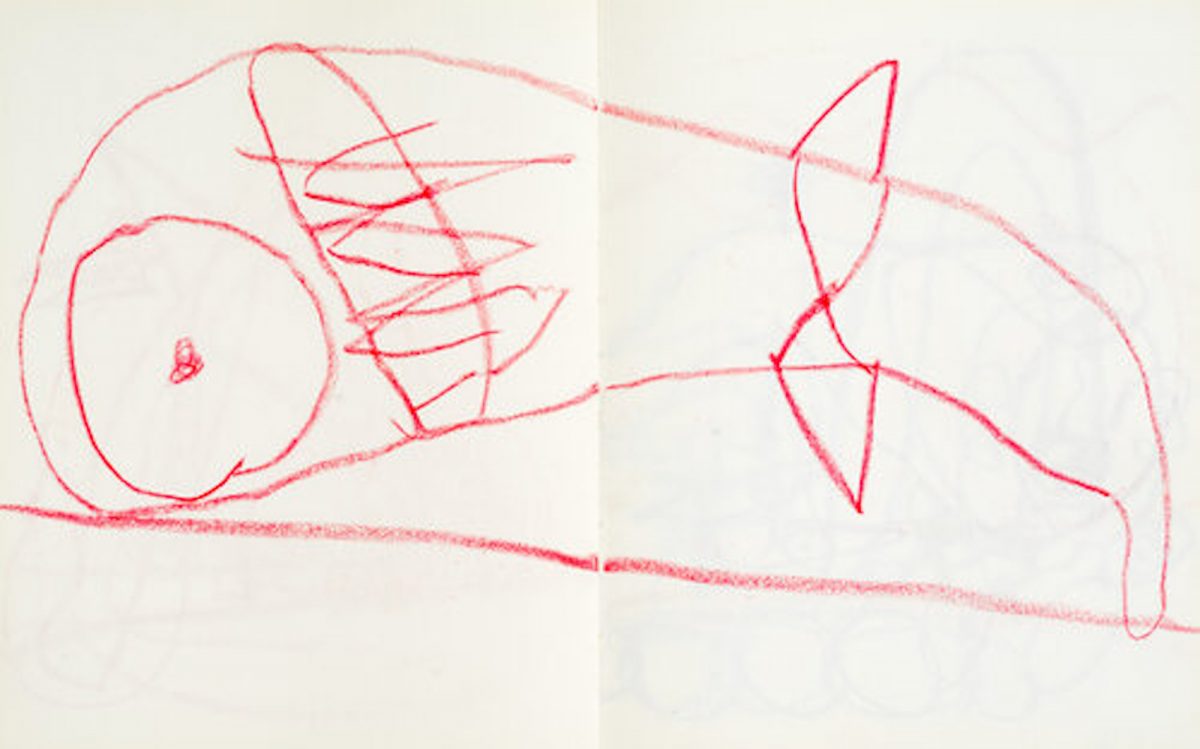

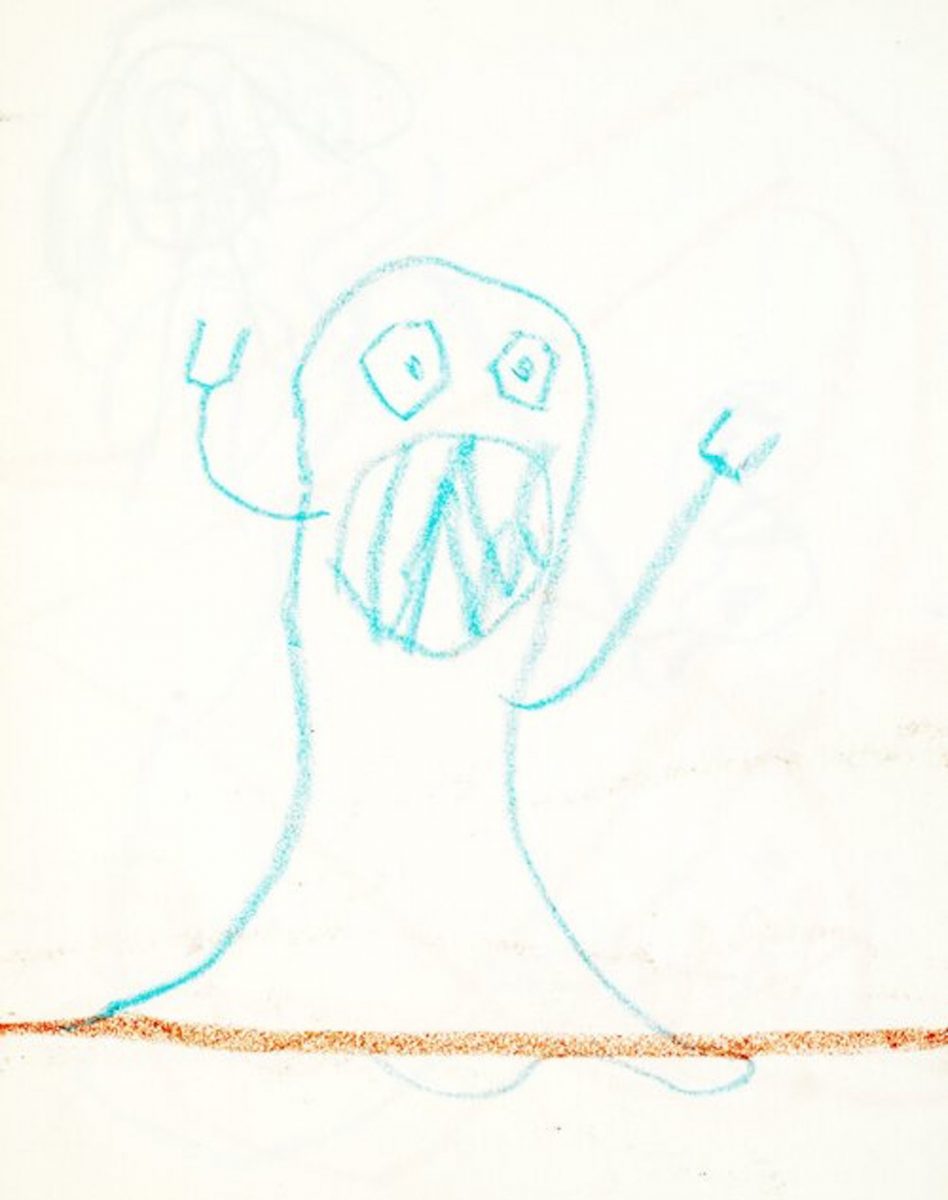

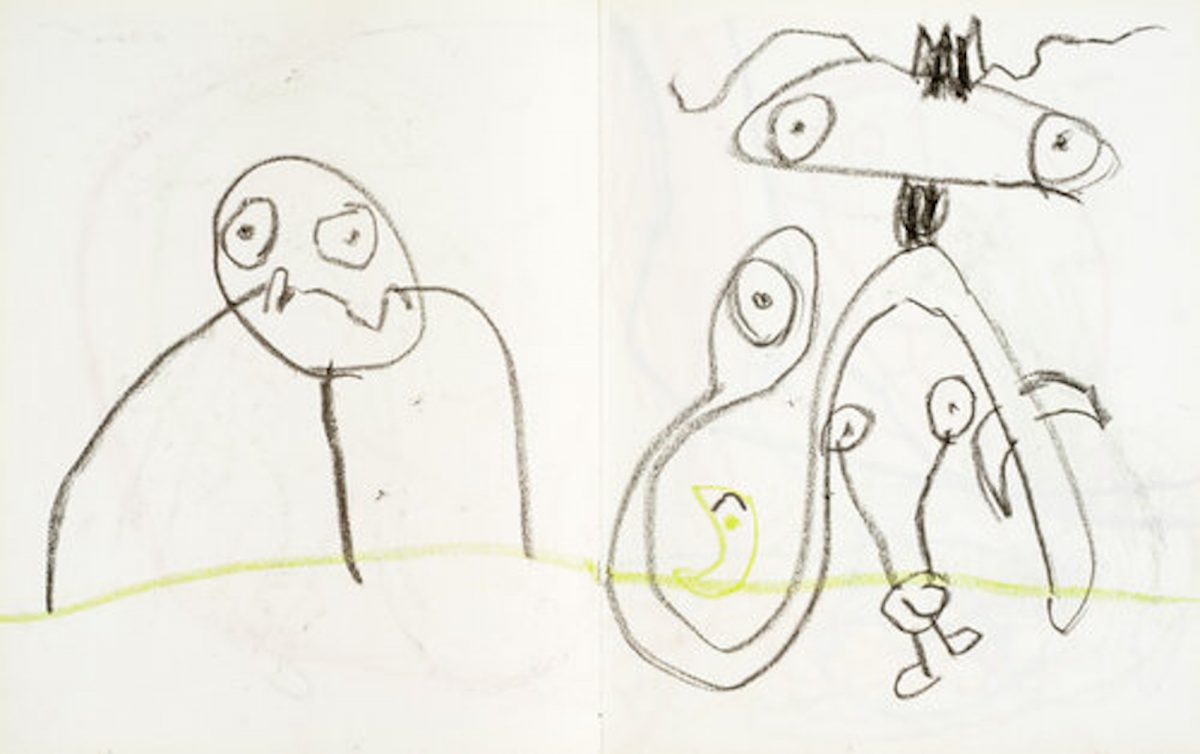

Now a new wave of artists is pushing things further by not only featuring kids but actively celebrating their independent creativity. Portuguese artist Pedro Guimaraes’ photobook Rato Tesoura Pistola features his son’s drawing and his daughter’s pancake masks alongside his own photographs. Luxembourg-based Cristina Dias de Magalhães’ forthcoming book Instincts. Same but Different features not only her own images but those of her twin children , including their drawings and photographs. Meanwhile American photographer Jacob Haupt’s Did I Scare You started out as a game between the photographer and his daughter, Talia, in which each tried to frighten the other. These books not only include the child’s perspective, they dare to suggest it can be interesting and perhaps even profound.

Dias de Magalhães’ interest in identities and how they are formed led her to include her daughters’ works in her own creative practice. “As I was researching and exploring various events, it just became obvious that my daughters’ quests are powerful and relevant,” she says. “My twin daughters started drawing at the age of two and a half. Their interactions, creativity, way of observing, learning and expressing themselves is fascinating, as it connects us to our own childhood, nature and our standing in the world.

“In this project my own kids have become the interpreter of our ever-evolving understanding of our surroundings, from native instincts to complex reasonings.”

Haupt, meanwhile, has described the process of becoming an adult as a “tragedy”. He’s interested in kids’ ability to create without judgement, to make art without thinking of it in those terms. “To them it might just be play,” he explains. “Once they grow up they start to become more aware of social perception and constructs. I think that shift is normal but it starts to build up walls: instead of just playing with colours, you are now painting. Even when you try to just play as an adult, that self-awareness and overthinking can kick in.”

“My twin daughters started drawing at the age of two and a half. Their interactions, creativity, learning and expressing themselves is fascinating”

Likewise, Guimaraes describes his collaborative book as “a small provocation” and a gesture against “the near-invisible status of all childish things”. He also rails against the exorcism of kids from contemporary working lives. “Modern society is built around people having their entire lives divided between the kids section and the professional section,” he says. “It’s an artificial divide, designed to make things work in a certain way, a so-called ‘productive society’.”

Guimaraes was impressed by his children’s sheer creativity, in particular his son’s “swift and resolute” approach to drawing, and Rato Tesoura Pistola (which translates as Mouse Scissors Pistol) was directly inspired by that resolve.

He is aware, though, that taking a child’s creative impulse so seriously is unusual. “Artists who have actually invited their own children to make part of their own creative process? I don’t know many of those, I’m afraid,” he says. “It is not very well accepted by the establishment.”

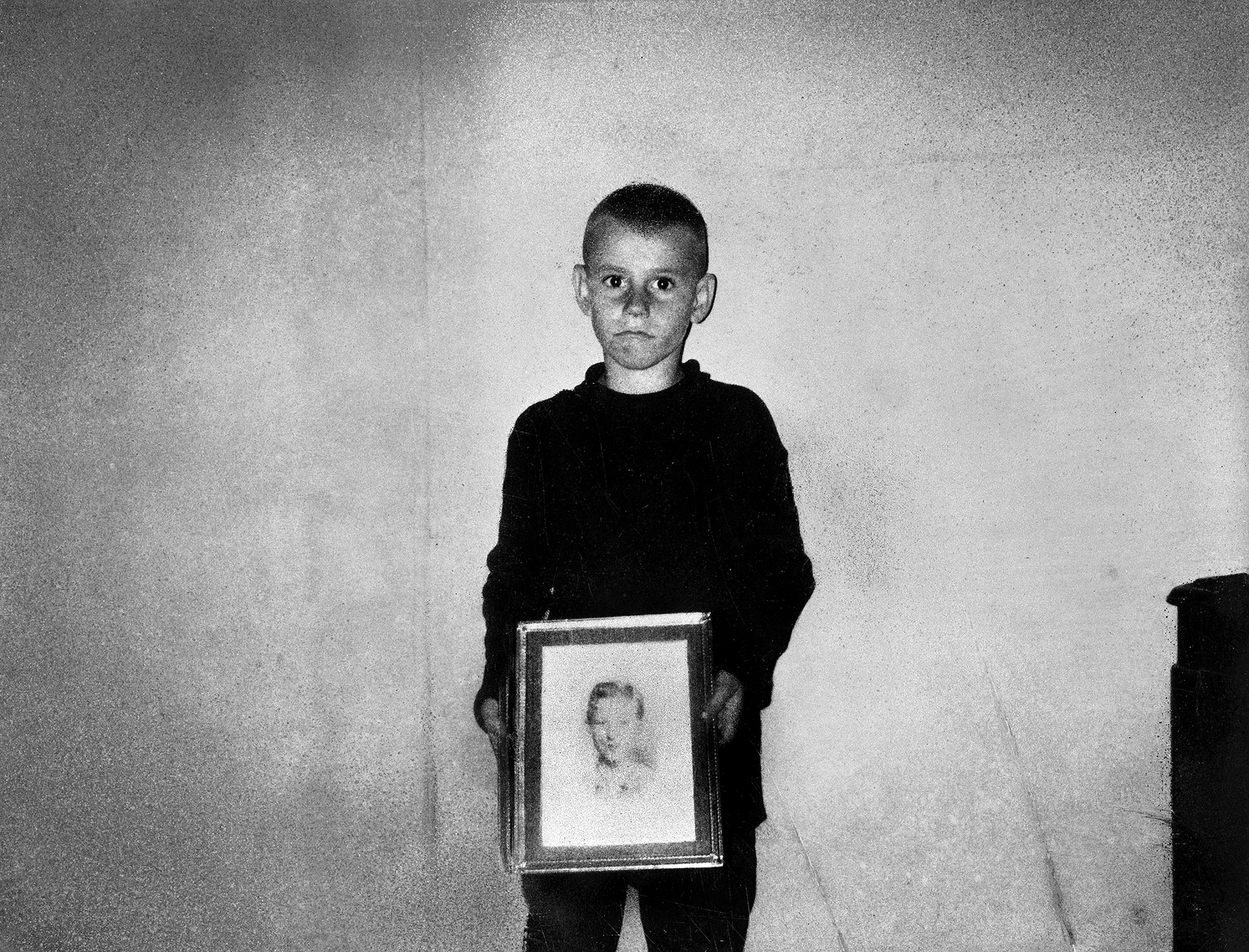

That sense of wider disapproval is familiar to American photographer Wendy Ewald, who has been working with kids since the late 1960s. She runs workshops in underprivileged communities, teaching children to use cameras. Her 1985 book Portraits and Dreams, made with youngsters in the Appalachian Mountains, was republished in 2020. She’s now publishing a, new book, The Devil is leaving his Cave, which combines images made with kids in Mexico in 1990 with new work made with young Mexican Americans in Chicago.

“Modern society is built around people having their entire lives divided between the kids section and the professional section. It’s an artificial divide”

As a woman working with kids, Ewald was often patronised in the male-dominated photography industry. “It was like this was not a serious enterprise, either educationally or photographically,” she says. “People couldn’t understand the pictures. The compositions were different, the subject matters were different, they just couldn’t see what I could see. Then I think people finally realised that the fact they hadn’t seen pictures like this before was important.”

Ewald hopes there will continue to be more interest in children’s creativity now, and more generally in children’s perspectives. If she is correct it’s long overdue. Children’s art is an established tradition in Surrealist and avant-garde collections, shown and published by Max Ernst and Jean Dubuffet among others. Ewald believes this interest is wider than just children, and part of a bigger cultural shift that has led to the questioning of established perspectives.

“I think there’s progression towards incorporating voices from underrepresented communities,” she concludes. “For those of us who have worked in this area so long, there’s the hope that this time it is really going to catch on. Because it’s not just the different countries or communities; the whole world is at stake.”

Diane Smyth is a freelance writer and curator. She is a former editor at the British Journal of Photography

Ewald images courtesy the artist and MACK