Elephant and Artsy have come together to present This Artwork Changed My Life, a creative collaboration that shares the stories of life-changing encounters with art. A new piece will be published every two weeks on both Elephant and Artsy. Together, our publications want to celebrate the personal and transformative power of art.

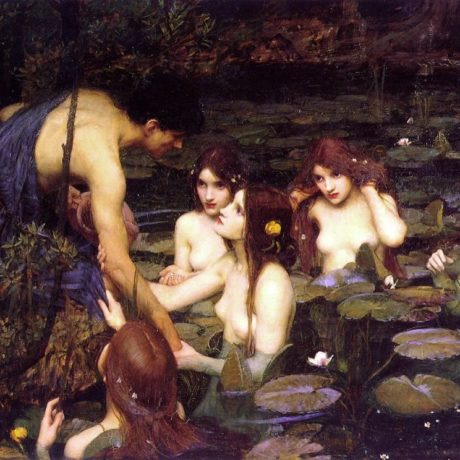

Out today on Artsy is George Millership on John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs.

Teenage girlhood can often feel all-encompassing. It is a confusing but romanticized time in our lives as we figure out who we want to be. Looking back now, it’s hard to define a clear line between happiness or sadness in my own teenage years. I blissfully recall long summers spent necking straight vodka on Brighton’s pebble beach, waiting for boys in bands outside of small venues. It is as if a hazily lensed camera, in the style of teen-drama queen Sofia Coppola, captured my entire existence aged thirteen to eighteen. In reality, growing up was also incredibly lonely. I struggled to come to terms with my own existence, and was largely unable to forge meaningful friendships. I failed to figure out what I actually liked, and would often adopt a projection of myself from my peers. Despite growing up in a nice, liberal city, I fled for university as soon as I could.

I first encountered Ghost World online, coming of age as one of the first teenagers with a readily-accessible internet connection. I spent my formative years scrolling through Tumblr for hours on end. The micro-blogging platform has since been largely abandoned due to its ban on the use of “adult” imagery, as well as us all moving en-masse to Instagram to perfect our personal brands. But Tumblr was once an outlet for countless future-millennials to cultivate community and find their peers. For many young women, the platform was an opportunity to explore avenues of creativity unrestricted by societal expectations. I would spend hours on it after school. Always too self-conscious to make any attempt at creating original content of my own, I would instead use the site to research, admire and collect endless cultural references. Like solving a jigsaw puzzle, I began to use what I found online to piece together who I wanted to be.

On any given day, screen grabs from films I’d never previously heard of and images from old fashion editorials would litter my feed. The work of Jenny Holzer and Cindy Sherman

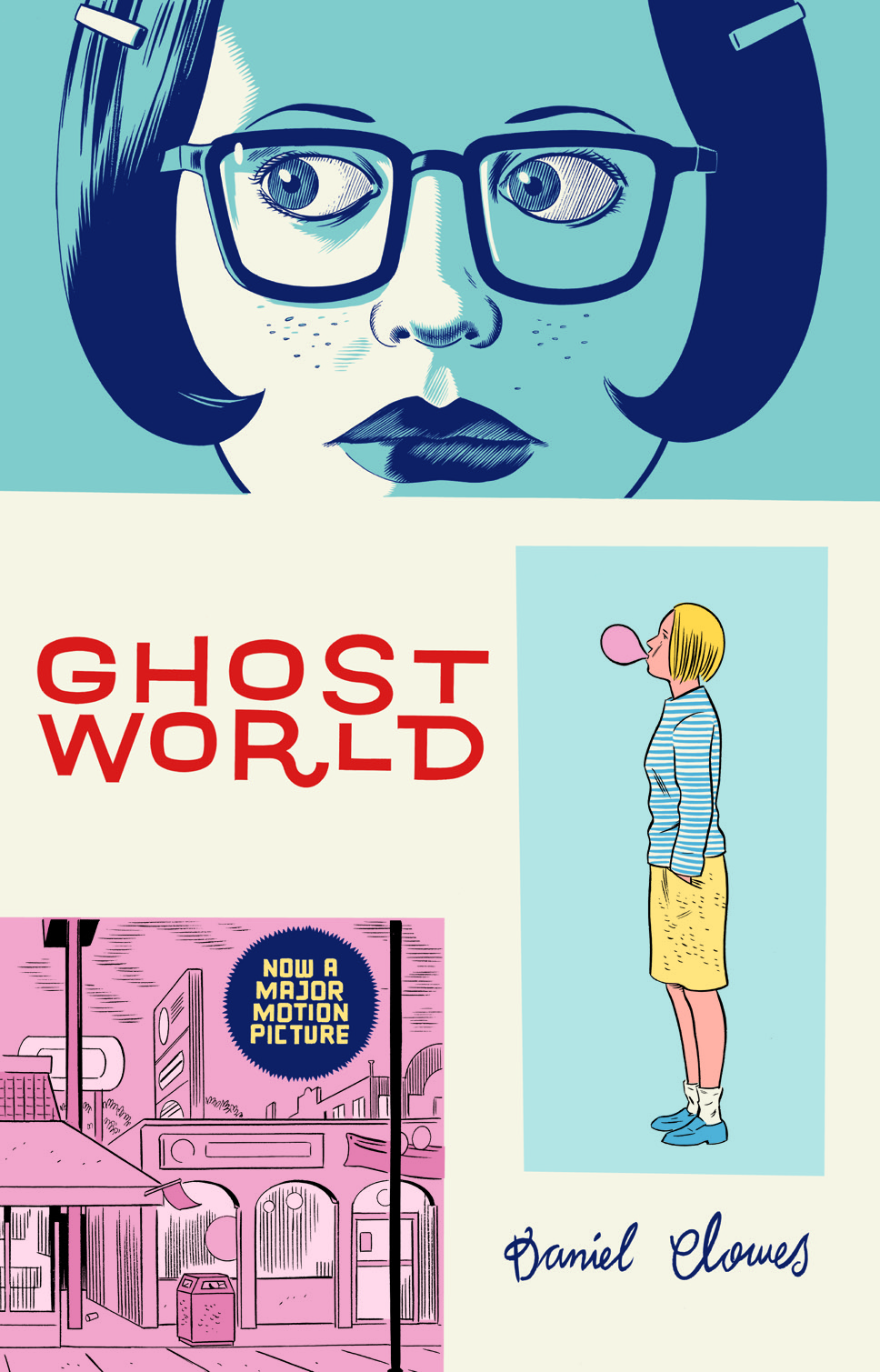

would appear side-by-side with original artwork created by then-unknown teenage girls such as Petra Collins, Maisie Cousins and Rachel Hodgson. All three were struggling through the mess of femininity in search of their own place in the world. It was on Tumblr that I first stumbled across a panel from Ghost World, although the original graphic novel was first released in 1997—three years after I was born. I initially bought the film adaptation on VHS at a local charity shop, but quickly sought out the story’s comic book origins, penned by Chicago-native Daniel Clowes.

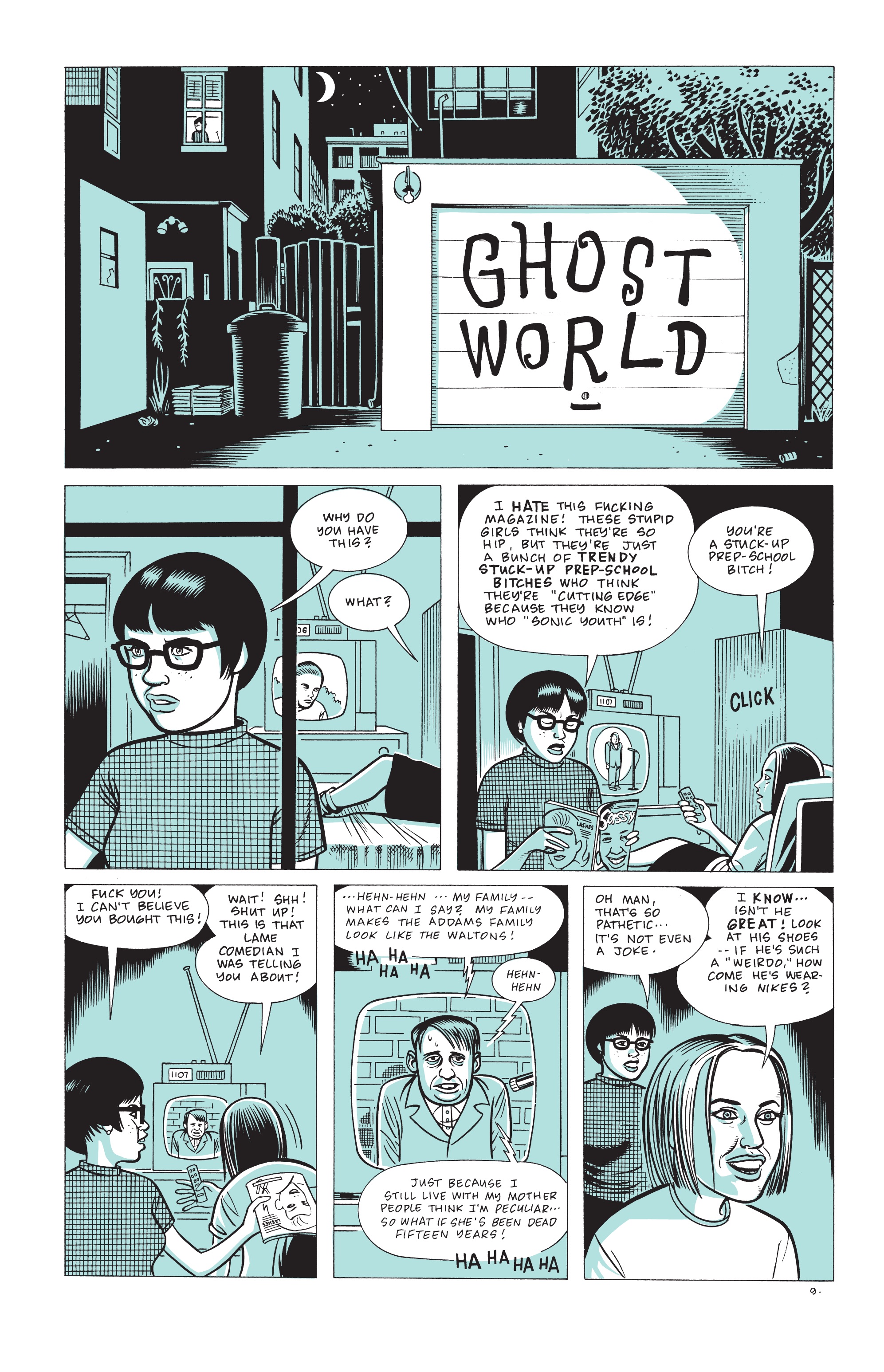

Despite gorging on teen movies, I struggled to find an image that felt close to my own. I pinned pages ripped from magazines up on my walls and obsessively followed artists my age on the internet, but I couldn’t get close enough to them. Reading Ghost World was different. As I followed eighteen-year-old best friends Enid Coleslaw and Rebecca Doppelmeyer through one long summer, this was the first time that I had found the teenage experience presented as anything but the best years of your life.

“This was the first time that I had found the teenage experience presented as anything but the best years of your life”

For every time that I watched Cher Horowitz in Clueless fire up her digital wardrobe and head out on a shopping spree, Enid would dye her hair green out of boredom, or feel so self conscious in an outfit that she would strip-off on the street. For every instance during a John Hughes teen movie that a heroine from the wrong side of the tracks finds her Prince Charming, Ghost World’s protagonists would recall the disappointing reality of losing their virginities. Inked in black and lime green, Enid and Rebecca are frumpy and sometimes spotty. They move through their world making bad decisions and even worse fashion choices.

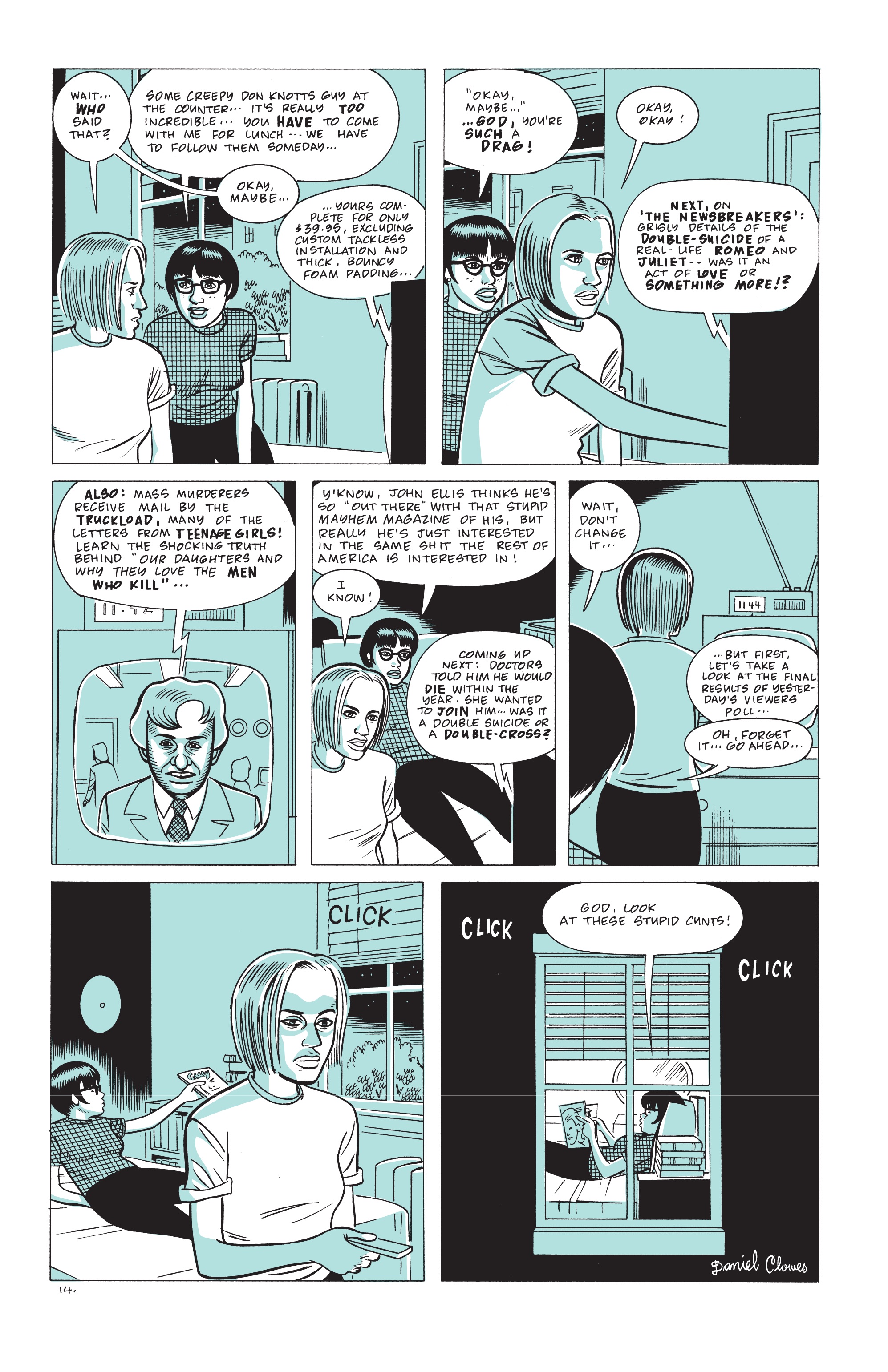

Enid spends most of her time belittling the interests of everyone around her. She loathes her father’s brash politics, berates her best friend Rebecca for her conventional beauty, and snipes at the television talk shows she spends her evenings watching. As an apathetic teenage girl, I couldn’t help but relate to the idea that I wasn’t the problem. I, too, often felt that it was in fact the rest of the world that had everything wrong with it.

On the surface, Ghost World could be read as a manifesto on how to not care about the world you live in. But for every reggae-listening white boy that Enid criticizes Rebecca for finding cute, she is cultivating her own obsessions. First, there are the “satanists” who occupy the local diner for lunch and dinner. Then there is her small stuffed toy who she can’t bear to part with during a yard sale. The sincerity of Enid reflected the weirdness I felt inside myself. During her gleeful raid of the local sex shop for stripper shoes and rubber masks, I began to feel more comfortable sitting with my own interests. Piece by piece, Enid taught me that the problem wasn’t caring too little. Rather, I realized that her rejection of the world—like my own—came from caring so much that it begins to hurt.

Enid and Rebecca’s friendship is as heartbreaking and mundane as many of my most significant partnerships from over the years. The two are inseparable, but bound together by the things they hate rather than what they adore. Their love language is the time they spend criticising everything about their circumstances, which have led them to spend their days populating local diners and walking long empty streets together. Despite a relationship built on dislike, the one thing the pair share is a genuine adoration for each other. Although both must deal with their own sadness, their friendship becomes the light in their lives.

“I realized that Enid’s rejection of the world—like my own—came from caring so much that it begins to hurt”

In Daniel Clowes’ graphic novel, there are no happy endings. There is no iconic love story, no glow-up and no dreams finally fulfilled. Enid and Rebecca slowly drift apart. The two simply start seeing each other less, until less becomes almost never. Their breakup is painful because of the lack of drama, as they slowly come to the realization that their distaste for everything else in the universe isn’t enough to keep them together. It’s world-shattering without being melodramatic. The months following their untethering is as uncomfortable as the period in which you continue to follow a former best friend on Instagram, after deciding to never speak to them again.

In the final panels of the graphic novel, Enid turns her back on Rebecca through the glass of a coffee shop and boards a bus to nowhere. Just as when I fled my hometown, it’s neither conclusive or final. Instead, it’s just a continuation of life. Like growing up, their coming apart is inevitable. Ghost World taught me that to embrace loneliness in the name of self-growth is a braver feat than to remain stagnant and clinging on to the person, place or thing that once made you feel whole.

All images courtesy of Fantagraphics

Did an artwork change your life?

Artsy and Elephant are looking for new and experienced writers alike to share their own essays about one specific work of art that had a personal impact. If you’d like to contribute, send a 100-word synopsis of your story to office@elephant.art with the subject line “This Artwork Changed My Life.”

Head to Artsy to read their latest story in the series, a piece on John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs

READ NOW