The role of a curator has long been defined as a custodian, one who preserves and protects a museum’s legacy, and more latterly as someone who sets the tone of the art world avant-garde, bringing together artists in a manner that serves their vision. Historically, the view has been Eurocentric, and the position both coveted and somewhat inaccessible. However, a new wave of curators is approaching the role from fresh perspectives, bringing previously under-represented artists to the fore.

“That’s definitely why I got into curating,” says Larry Ossei-Mensah, a Ghanaian-American writer and curator who is a co-founder of the ARTNOIR collective, which promotes equity across the cultural sector. He recently curated the exhibition Amoako Boafo: Soul of Black Folks at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. “When I started curating in 2008, it was a very different climate, very homogeneous. I didn’t feel like there were enough forums and avenues to have these kinds of conversations, to push the envelope.”

“I’ve been thinking a lot about how to move away from the idea of a curator as an arbiter of taste,” says Carla Acevedo-Yates, a Puerto Rico-born curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Chicago. “As an institutional curator, I need to think about what the work is doing for the viewer, for art history, and in terms of thinking about contemporary issues. I’m very interested in how art can help us think more critically about the world in which we live in.”

Acevedo-Yates’s most recent curatorial work, the Focus section of The Armory Show in New York, has been noted for its global perspective. “The programme I’ve been developing at the MCA is very much tied to Latin-X, Latin American and indigenous artists, as well as approaching issues around environmental destruction, colonialism, racism and gender violence,” Acevedo-Yates says.

Across 30 booths of The Armory Show, the Focus section was titled Landscape Undone and spanned artists and galleries from and representing “the so-called ‘Global South’, for lack of a better term”, says Acevedo-Yates. One of the key artists was Costa Rica-born Priscilla Monge, who “has been doing a lot of work since the 1980s and 1990s from a feminist perspective, denouncing gender violence and patriarchal structures”. Another was Claudia Peña Salinas. “Her work incorporates Mesoamerican mythologies and histories, but also dialogues with western art histories of minimalism and geometric abstraction,” says Acevedo-Yates, who also highlights the work of Jamaica-born Leasho Johnson, French-Caribbean artist Julien Creuzet and Puerto Rican-American David Antonio Cruz.

“A lot of the artists reside in the US but may be of Asian, African or Caribbean descent. It’s a way to work through my own identity”

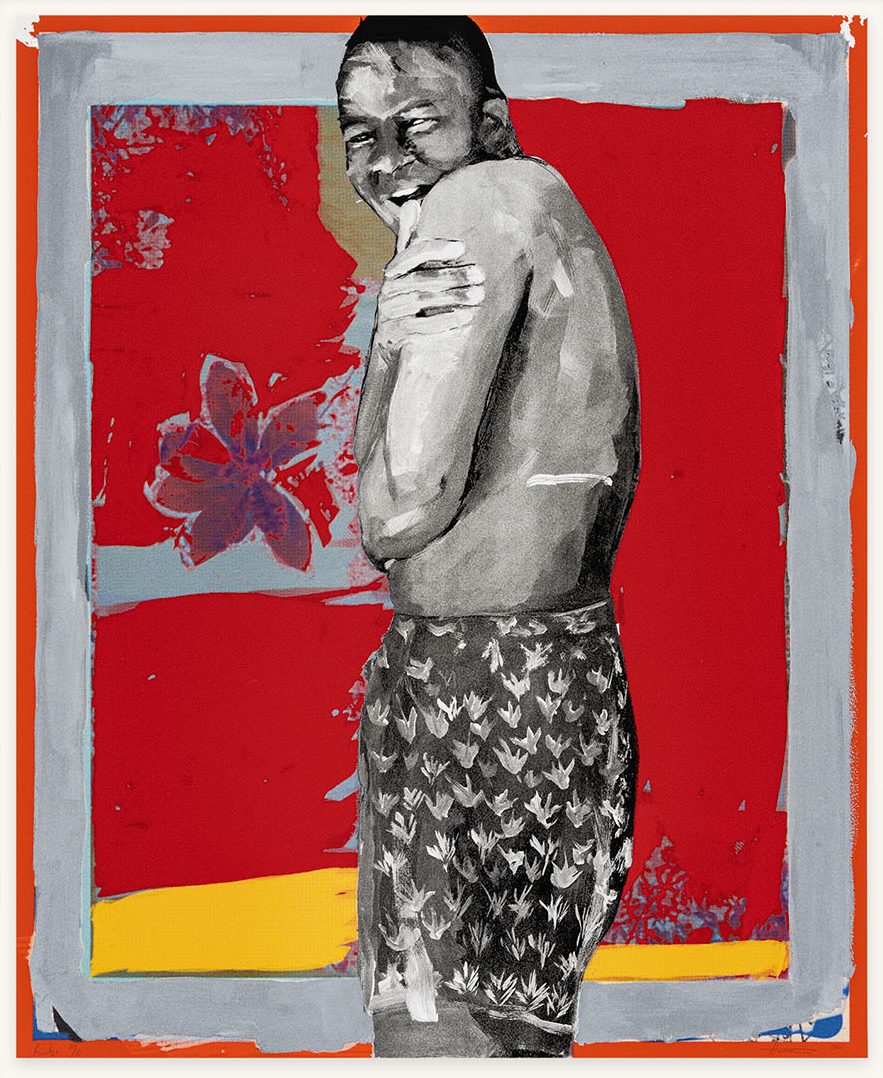

Cruz’s practice was represented at The Armory Show with a series of paintings and drawings. “He’s a technically incredible painter,” says Acevedo-Yates of his joyfully bright groupings of figures based around “one’s chosen family from a queer perspective. It’s really beautiful how he places people like they’re falling into each other, with the idea of support and love, touch and caring translated into a painterly style that is very relevant right now.” His drawings, meanwhile, focus on the Ceiba tree, which is sacred to indigenous communities in Puerto Rico.

Ossei-Mensah’s current show at Ben Brown Fine Arts in London’s Mayfair centres on artists from African and Asian diasporas. Titled Ghosts of Empires II (on until October 22), it is an extension of an earlier exhibition in Hong Kong. “I was tasked with putting out a show that could be fresh and interesting for audiences in both Hong Kong and London,” says Ossei-Mensah, whose selection looks at the legacy of colonialism. “It’s also about how you navigate a bicultural identity,” he adds. “A lot of the artists reside in the US but may be of Asian, African or Caribbean descent. For me, honestly, it’s a way to work through my own identity. I was born and raised in the States and both of my parents are from Ghana.”

“To be at a Biennale dominated by women and queers just felt so wonderful and powerful”

The show features a number of well-known names (including Hurvin Anderson, Chris Ofili and Theaster Gates) as well as more emerging talent. Ossei-Mensah pinpoints Jamaican-born artist Paul Anthony Smith, whose photographs of the Notting Hill Carnival are dotted with a picotage technique, removing small sections so that figures appear to be disappearing.

“It’s been really interesting to see what happens when you put a painting by Hurvin Anderson, who is British West Indian, in conversation with a Tidawhitney Lek, who is Cambodian American, or an Adam de Boer, who uses a similar palette,” says Ossei-Mensah. “I think that it’s the beginning of a continual conversation,” he adds, citing the Wonder Women show at Jeffrey Deitch in New York earlier this year, which presented work by 30 Asian American and diasporic women and non-binary artists, as well as Ekow Eshun’s In the Black Fantastic at the Hayward Gallery, as further thought-provoking examples.

Gemma Rolls-Bentley is the chief curator of digital platform Avant Arte and a co-chair of London’s Queer Circle, a new space for LGBTQ+ arts and culture. For her, a turning point in art-world conversations about diversity and representation was this year’s Venice Biennale, curated by Cecilia Alemani. “To be at a Biennale dominated by women and queers just felt so wonderful and powerful,” she says. “It was a real landmark moment for the art world, and I would like to hope that there is no going back now that she’s done that.”

At Avant Arte, what appeals to Rolls-Bentley is the brand’s mission to “make art radically more accessible”, and its appeal to a young generation. “I’m sure that one of the reasons they invited me to work with them is that I am a champion for diversity,” she says, adding that her broad definition spans “the identity of the artists, thinking about gender, ethnicity and nationality”, but also what career stage they are at and what medium they work in.

“When I started curating, it was very homogeneous. There weren’t enough forums and avenues to have these conversations”

“Avant Arte is a huge community and it’s a really good opportunity to use that platform for good, to raise money and raise awareness about the issues that artists care about,” she says. This includes a print collaboration

with Zimbabwe-born painter Kudzanai-Violet Hwami (released on 23 September), which will raise funds for Queer Circle. Rolls-Bentley has also introduced public art as an initiative at Avant Arte. The first commission is a sculpture by Tschabalala Self that will be unveiled in King’s Cross in October.

As an independent curator, Rolls-Bentley is guest-curating a queer arts and culture festival for the Tom of Finland Foundation in London (8 and 9 October) and was recently involved with an exhibition of April Bey’s work at Simon Lee gallery (until October 1). “April grew up in the Bahamas, lives in Los Angeles, and has created a beautiful, vibrant world in the gallery called Atlantica, which is free from prejudice,” says Rolls-Bentley. “She very influenced by Afro-futurism, queer culture, Instagram influencers, and exploring themes of self-love, body positivity and friendships.”

Rolls-Bentley admits that the art-world “still has a lot of work to do” in terms of diversity, but right now there is plenty to celebrate.

Victoria Woodcock is a freelance journalist and a contributing editor at HTSI