In the Instagram age, we are used to photographs that try to draw us in, showcased by content creators who know that the highest aesthetic appeal will translate into more views, more clicks, more likes; the commercial is familiar. Images that repel, that challenge or that just make us feel uncomfortable should therefore drive us off, but somehow they provide an even greater lure, and at Unseen Amsterdam, once your eye is caught, you will find yourself unable to look away.

In the Instagram age, we are used to photographs that try to draw us in, showcased by content creators who know that the highest aesthetic appeal will translate into more views, more clicks, more likes; the commercial is familiar. Images that repel, that challenge or that just make us feel uncomfortable should therefore drive us off, but somehow they provide an even greater lure, and at Unseen Amsterdam, once your eye is caught, you will find yourself unable to look away.

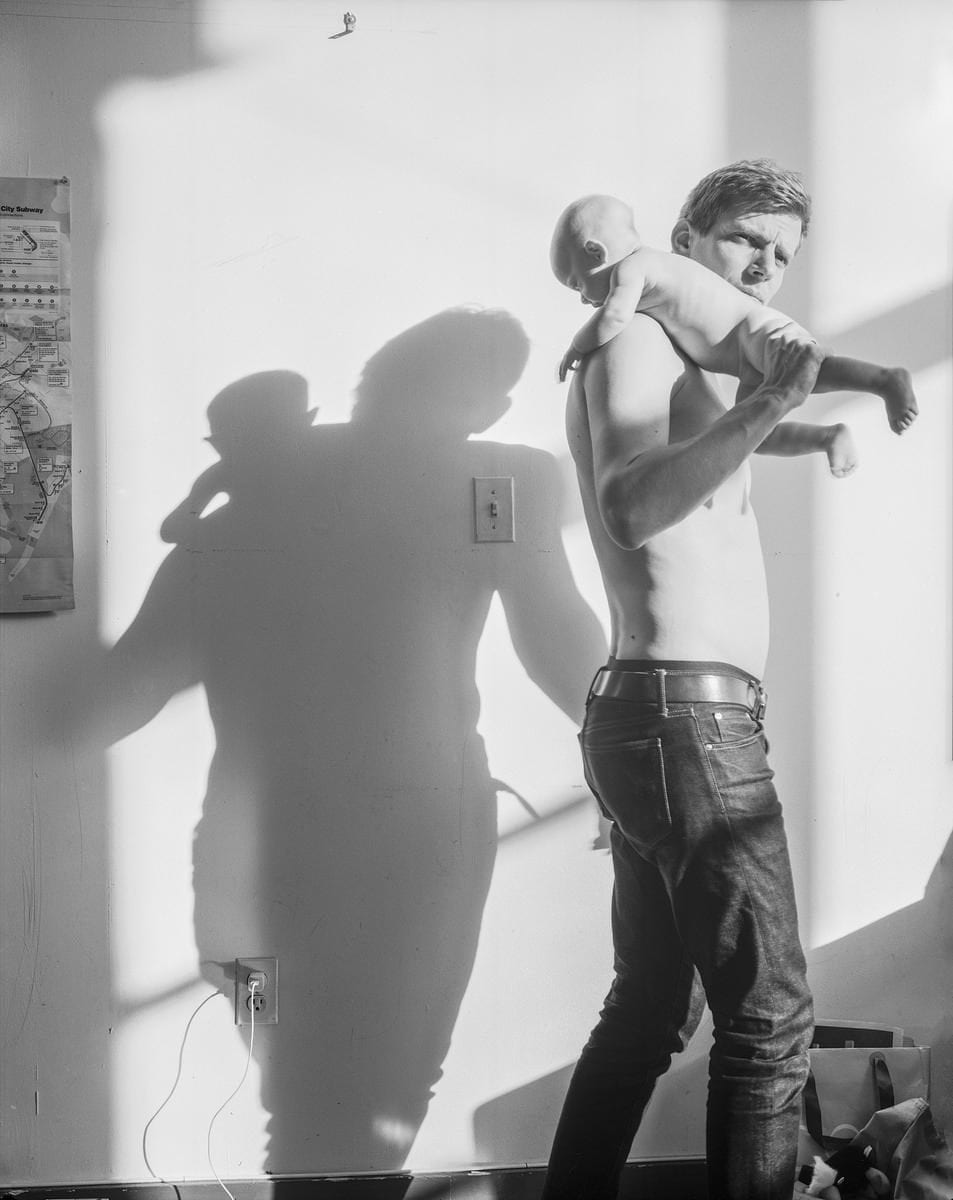

Izumi Miyazuki presents her self-portrait Taraco which, like many of her works, makes us look at food with a new eye, confronting the fact that the food we find the most tasty is often objectively gross-looking. The portrait is beguilingly gruesome, yet pastel-cute enough that we are not entirely put off. Peter Puklus’s How to Carry a Weight, sees a baby slung unceremoniously over its semi-clothed father’s shoulder. It’s nerve-wracking, especially as the father glances back as if checking that we’re watching; he walks away with his infant held about as preciously as an axe on the shoulder of a lumberjack.

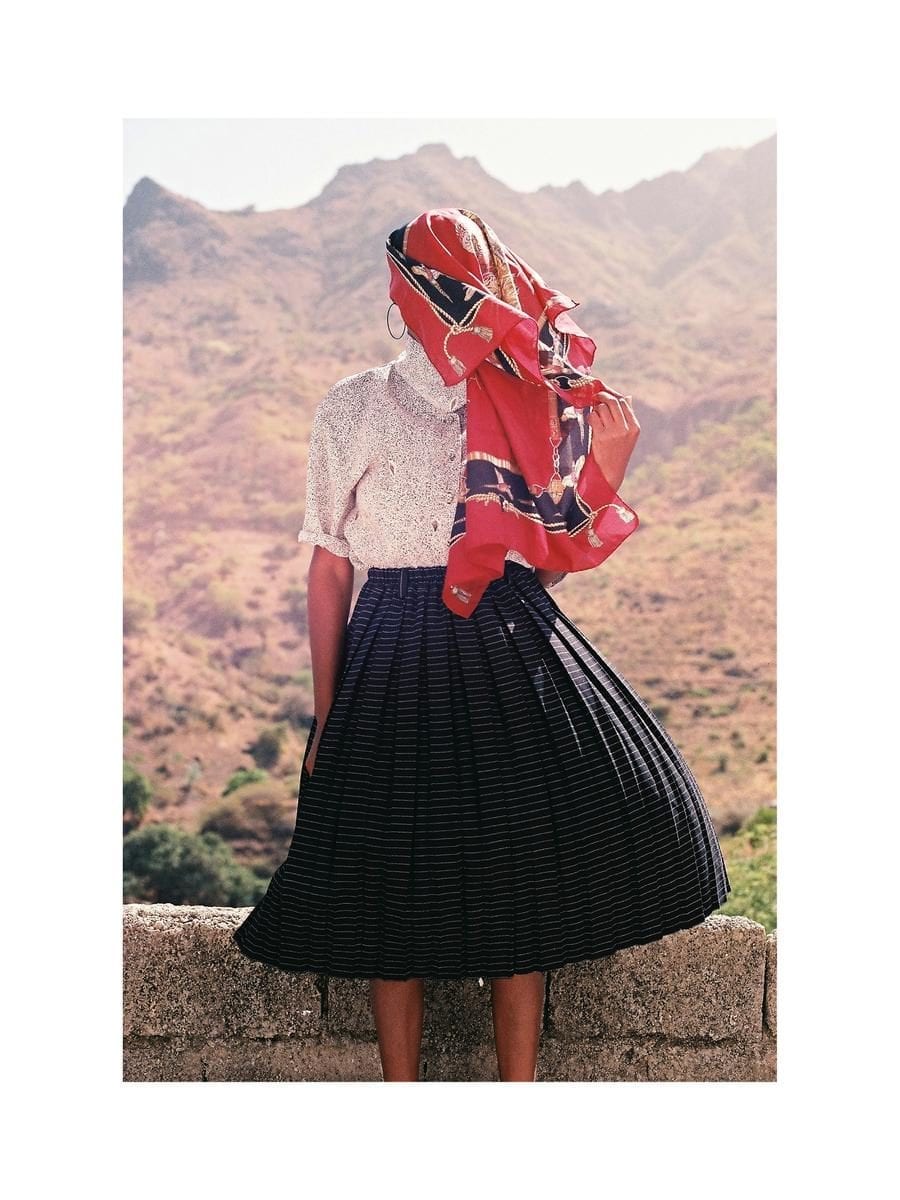

While the subject of Puklus’ photograph seems to be actively trying to provoke discomfort in his viewers, the discomfort created by Alexia Fiasco’s Gina, My Aunt, Crying Woman, is not a matter of provocation but a feeling of being in the way. The woman does not invite us to look at her, and in fact she seems to discourage it; yet, as a dynamically vibrant subject, she continues to pull the eye in.

“Images that repel, that challenge or that just make us feel uncomfortable should drive us off, but somehow they provide an even greater lure”

Perhaps it is her distinct femininity which means that we keep looking, despite her seeming objection. Women are typically accorded less agency over their own bodies, with the ubiquity of the male gaze frequently rendering them objects. Emi Anrakuji’s untitled self-portrait confronts this. The idea of the selfie makes us ask, who is this picture for, and for whom are you posing? Unlike Fiasco’s subject, Anrakuji doesn’t mind us looking but, in full possession of her own body, she shows us that she’s not there for us.

In contrast, Inka and Niclas Lindergård’s K4 Ultra HD 2 is all about including the viewer in a shared experience of a moment of real time, to avoid the “you had to be there” explanation of beauty, and catch in an image the personal emotional gut reaction of a visual experience. It is the ultimate invitation to look, to feel and to connect.

Jana Sophia Nolle’s The Living Room creates an entirely different, altogether more jarring discomfort. Her photograph shows a recreation of a temporary shelter erected by a homeless person who she encountered in San Francisco. Re-constructed inside the minimalist opulence of an upper-class San Francisco apartment, the two domestic set-ups clash, and the attempt at personal expression and decoration in the shelter is heart-rending. Like much of the works on display, we feel compelled to witness even as we would rather look away.