Simon Faithfull, still from Re-Enactment for a Future Scenario No.2: Cape Romano, 2019

What is the role of art in dealing with environmental destruction? Artists can choose to evoke the consequences subtly or call direct attention to the issues. In doing so, they might use recycled materials or look for ways of reducing their own carbon footprint. As for possible solutions, many artistic pseudo-proposals highlight the inadequacy of official responses to date rather than coming up with practical answers. Asking an artist to find a real, powerful solution might be too big an ask, but it’s fair to say that any viable suggestion will require a connection between the technical and the natural.

Simon Faithfull

The English multimedia artist Simon Faithfull’s projects typically see him roam the world both to test performatively and report back on its extremes, often collaborating with scientists engaging with environmental issues. His newest films “re-enact” possible future scenarios by extrapolating from recent trends. Here he probes how our boundaries will shift, exploring the ruins of a futuristic beach house off the coast of Florida. The Cape Romano domes were built on dry land in 1972 before hurricanes and erosion left them stranded in open water. The sea, ominously, ruled most of Faithfull’s recent retrospective, Fathom, in Penzance.

Bettina von Arnim

In the 1960s, Paris-based artist Bettina von Arnim was already exploring the technological permeation of the human body by depicting cyborg-styled man-machine interfaces. It’s not surprising, then, that her recent, knowingly dramatic landscapes feature various artificial insertions, suggesting a conflict between the technical and natural. Here the foreground sits on a colour spectrum which hints at how the electric colours may have been exaggerated. It’s enough to remind you of how the classic European landscape is already a construction, even before the more malign aspects of human activity come fully to bear on it.

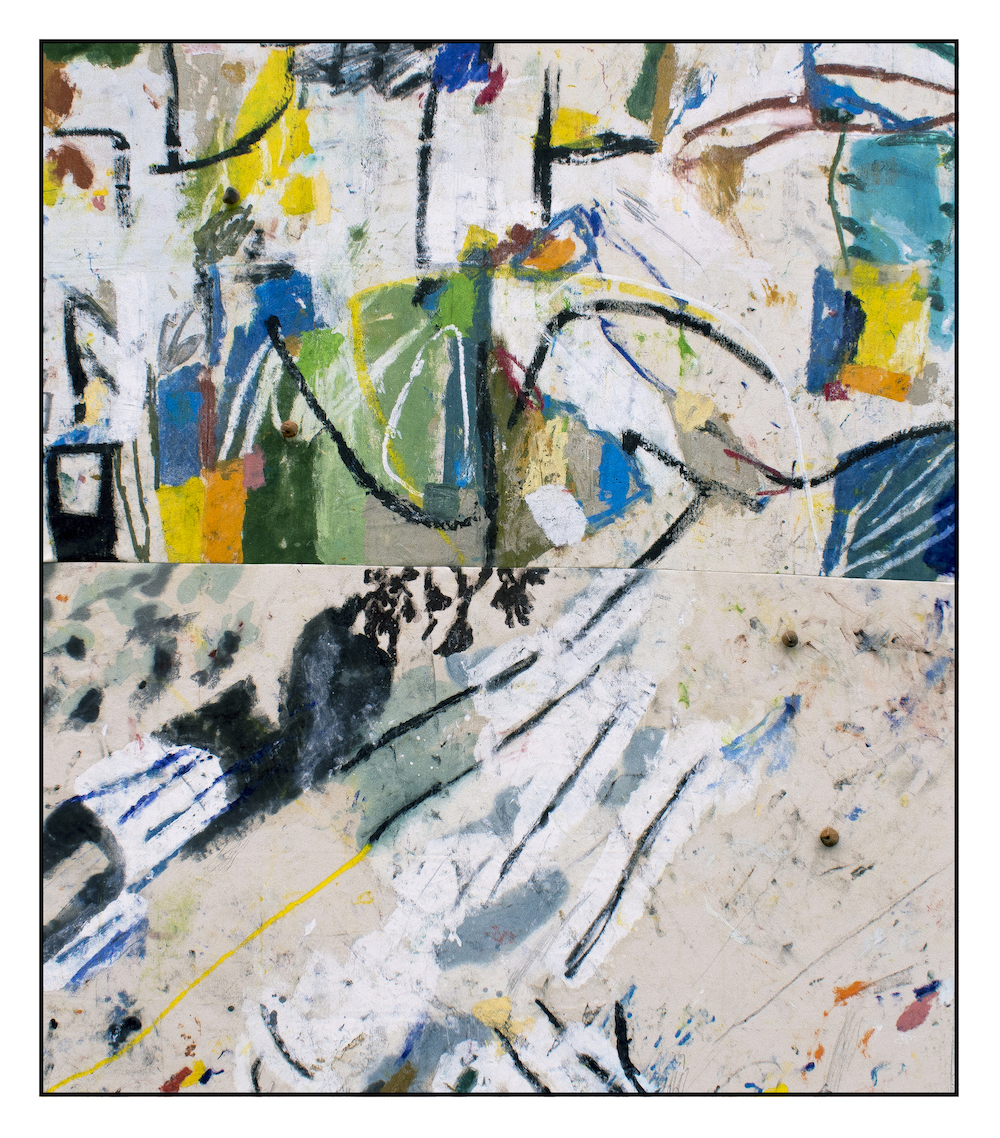

Peter Matthews

Peter Matthews takes plein-air painting to extremes as he works alongside oceans, seeking to capture his experiences of the sublime. He lives with his large spreads of unprimed canvas, carrying them on his back—they double up as sunscreen, roof or hammock. He lets the sea wash over them, attaches objects found on the shore, and is as likely to use sticks and stones as brushes to apply the paint. No wonder Matthews covers a lot of territory: Ek-Balam was made in part on the Pacific coast of Mexico and partly on the Cornish Atlantic coast—hence the two sections sewn together—and is named after an archaeological site where the Mayan way of using glyphs and signs inspired him.

- John Akomfrah, still from Purple, 2017

John Akomfrah

John Akomfrah’s immersive six-screen installation Purple explores the nature of the Anthropocene in overwhelming fashion through his typical combination of archival footage and newly shot film. Pictured is Scotland, but we see ten countries across an epic timespan from the Industrial Revolution to the digital age: the past always haunts the present in Akomfrah’s bricolage. A lone figure appears from time to time to bear witness, standing in for both the viewer and the artist to ask the climate change question he formulates as: “What is philosophically, ethically and morally at stake here if we continue on this course?”

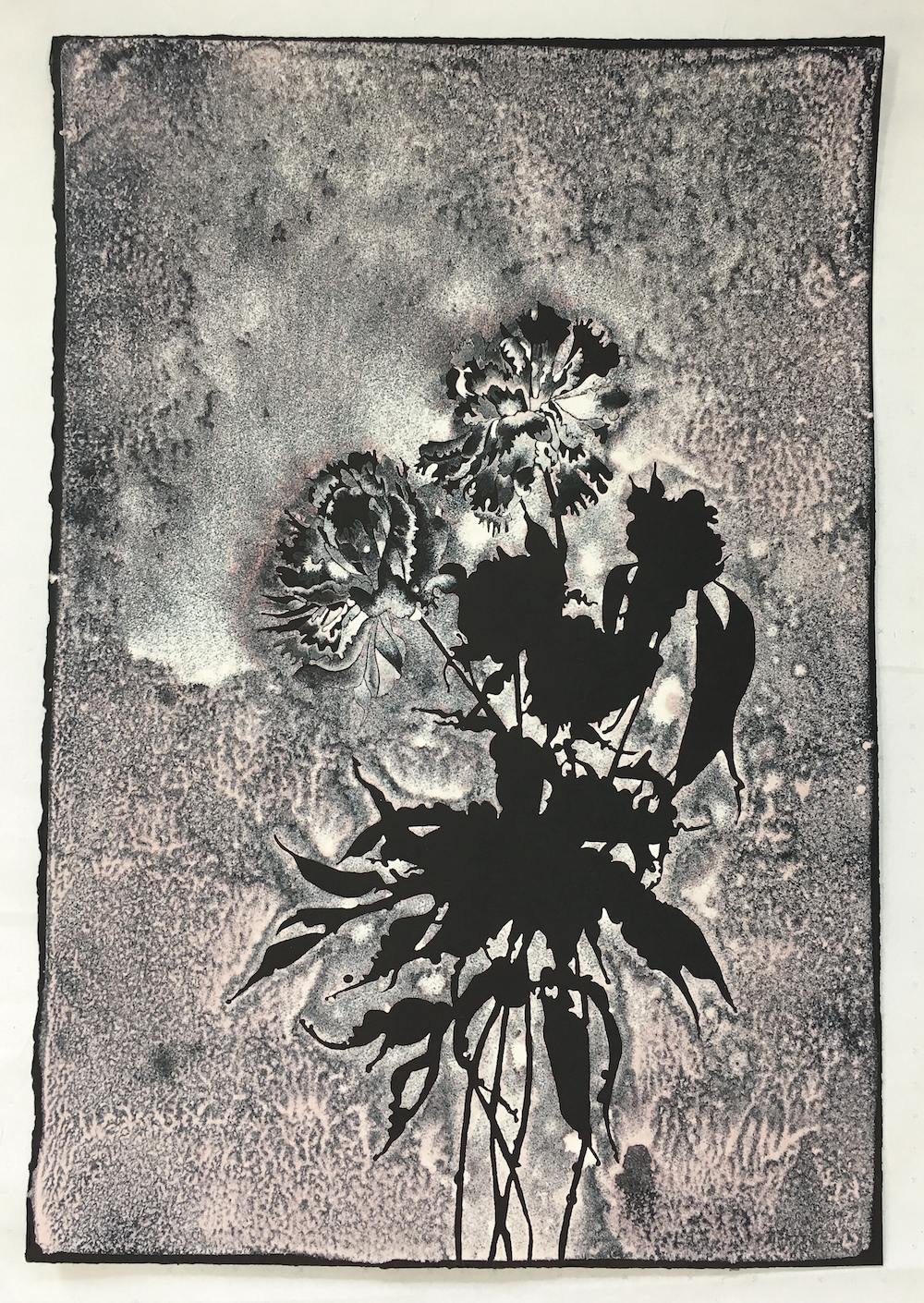

Hannah Maybank

British painter Hannah Maybank captures the dangerous beauty in blight, through a floral image which could stand in for the attraction we find in lifestyle choices that corrupt nature. These flowers carry a personal story as well as metaphorical potential. Sarah Bernhardt peonies are a staple of the cut flower industry, accounting for almost half the €50million annual Dutch peony sales, but these particular blooms originate from a clump which has been in the Maybank family since the 1920s. That makes them, says Hannah, “a living heirloom”. She adds that the peonies start off in small, tight buds before opening out more and more, and finally falling apart in a particularly dramatic slow-motion death.

- Anna Reivilä, Bond 29, 2017

Anna Reivilä

“Helsinki School” photographer Anna Reivilä “draws” on remote Finnish landscapes, using rope which she knots around trees, rocks and ice. This proves a beautifully ambiguous way to muse on our relationship with nature. The nets of rope, intuitively rather than systematically formed with sailor’s knots, hover between protection and strangulation. In the case of the ice used here, of course, rope is a particularly hopeless stay against melting, triggering the thought of how little chance we seem to have of protecting it in the larger scheme of global warming. Are current efforts no better than Reivilä’s rope?

Laure Prouvost

“Ideally,” as one of the 2013 Turner Prize-winner’s characteristic notices might say, “this work would save the world.” Laure Prouvost’s bunch of balloons turn out to be individually blown glass, as well as squirting breasts. They provide a quirkily absurd means of mothering the world through global cooling, though the immediate beneficiaries in this case are the goldfish swimming happily around a reef of two sunken smartphones. Come the time when there’s more plastic than coral in the sea, the world will need millions of Prouvost’s systems to be installed… Good maternal intentions, we might conclude, won’t be enough—but what else have we got?

This feature originally appeared in issue 41

BUY ISSUE 41