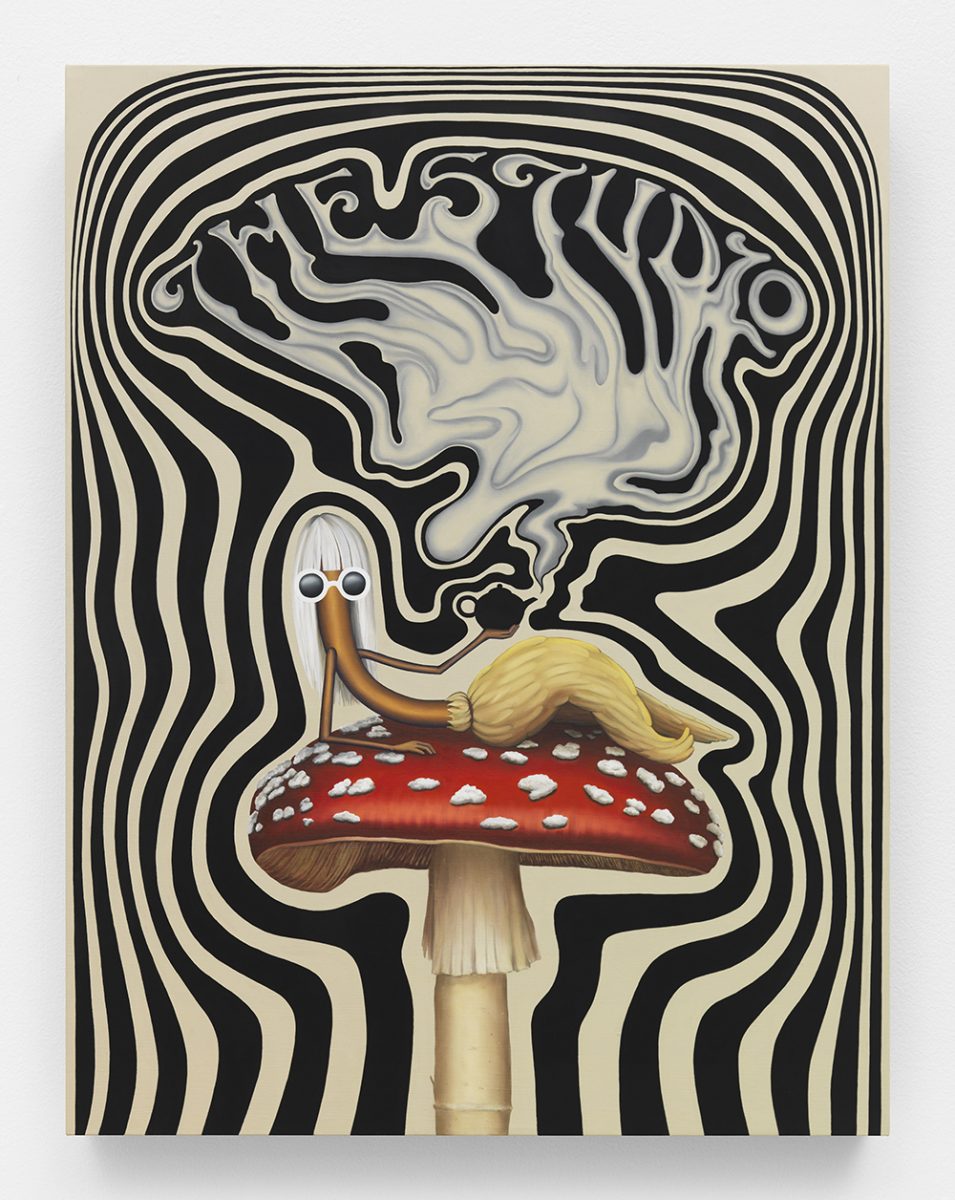

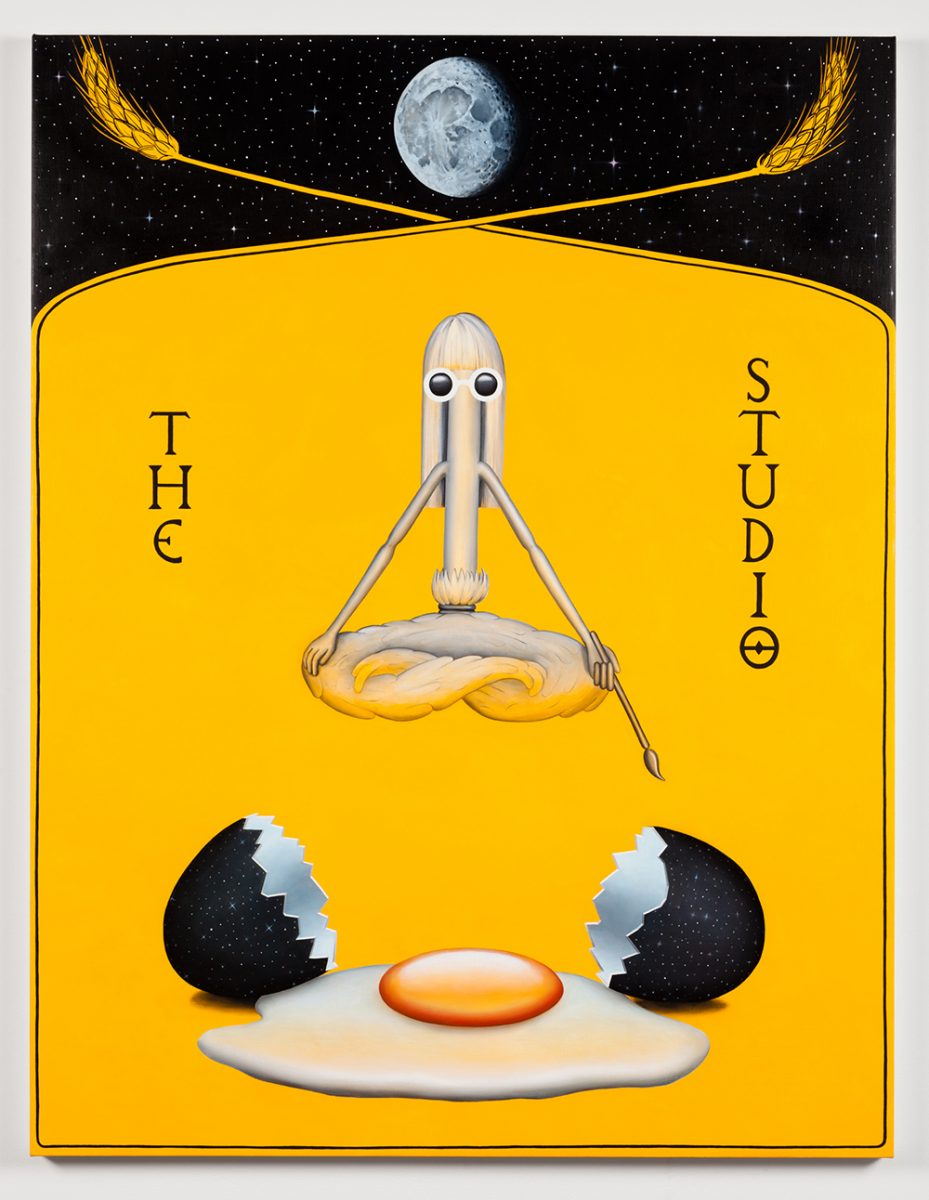

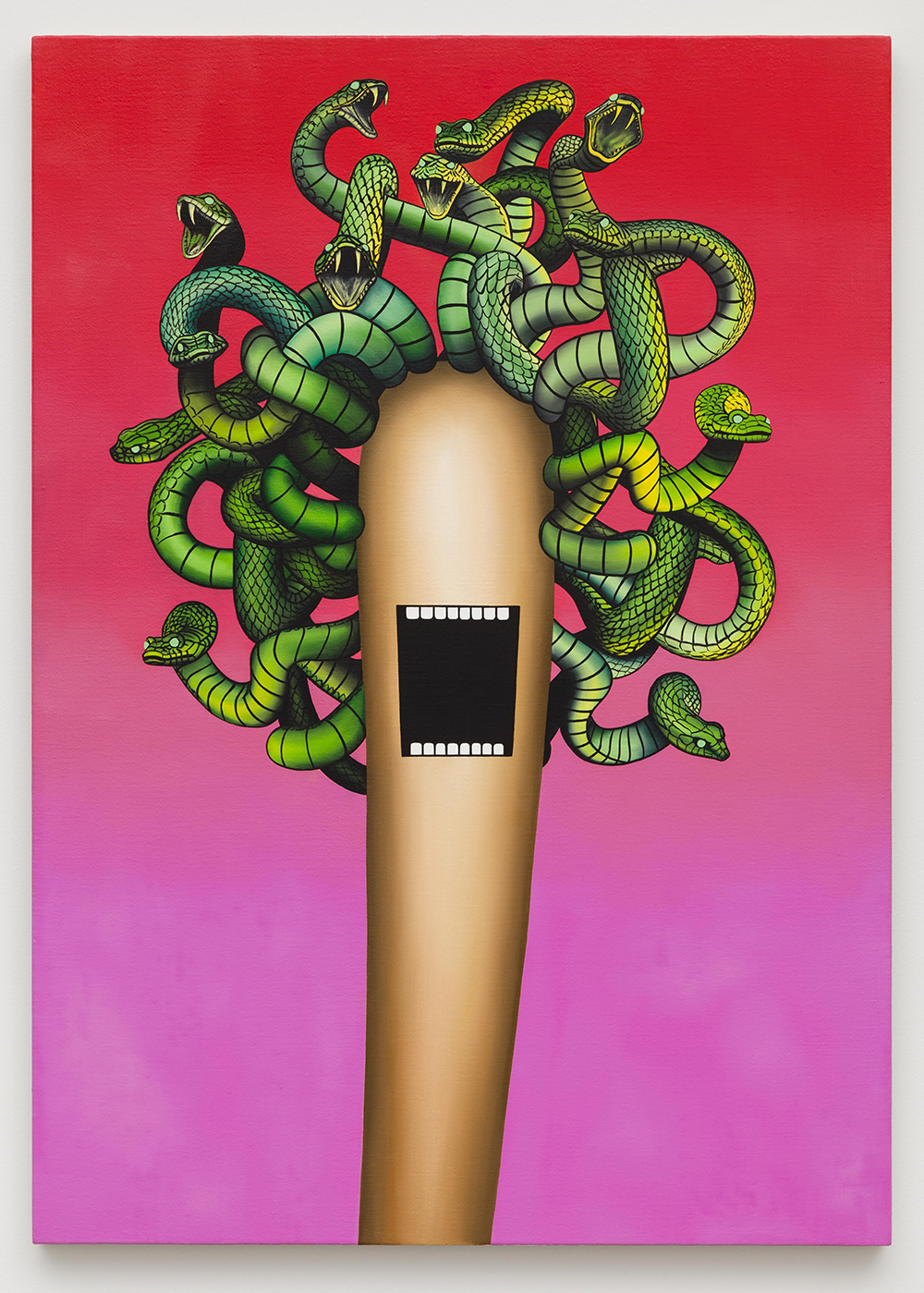

As the more than 250 images in this book demonstrate, Emily Mae Smith’s paintings riff on many recognisable tropes. Some call to mind the wild psychedelia of 1960s and 1970s album covers. Others reference Greek myths, with writhing snakes in place of human hair. One of her repeated characters, an animated broom with a hot dog sheen, harks back to Disney’s trippy

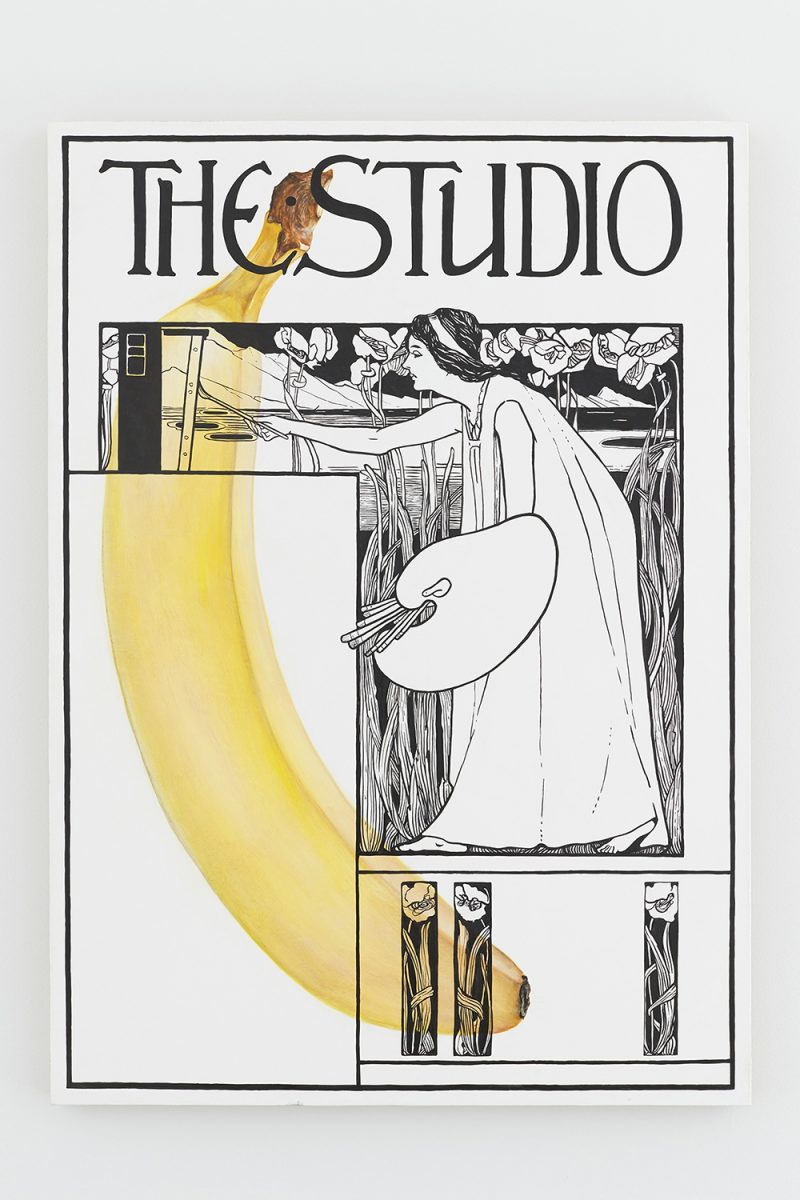

Fantasia (1940). The eponymous new monograph brings together a wide selection of the American artist’s works alongside a diverse range of inspirations, from The Velvet Underground’s iconic debut album cover to Linda Nochlin’s suggestive 1970s photography.

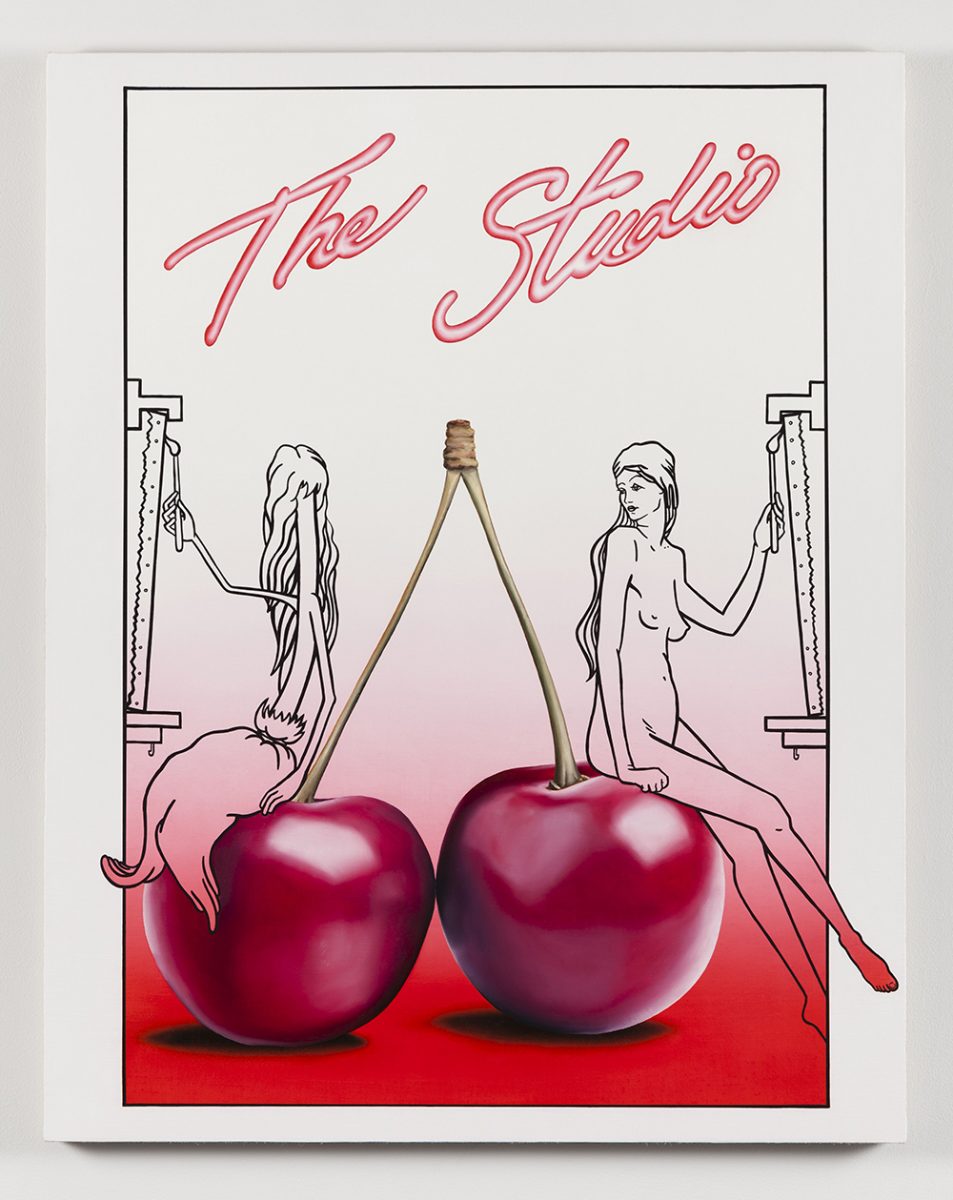

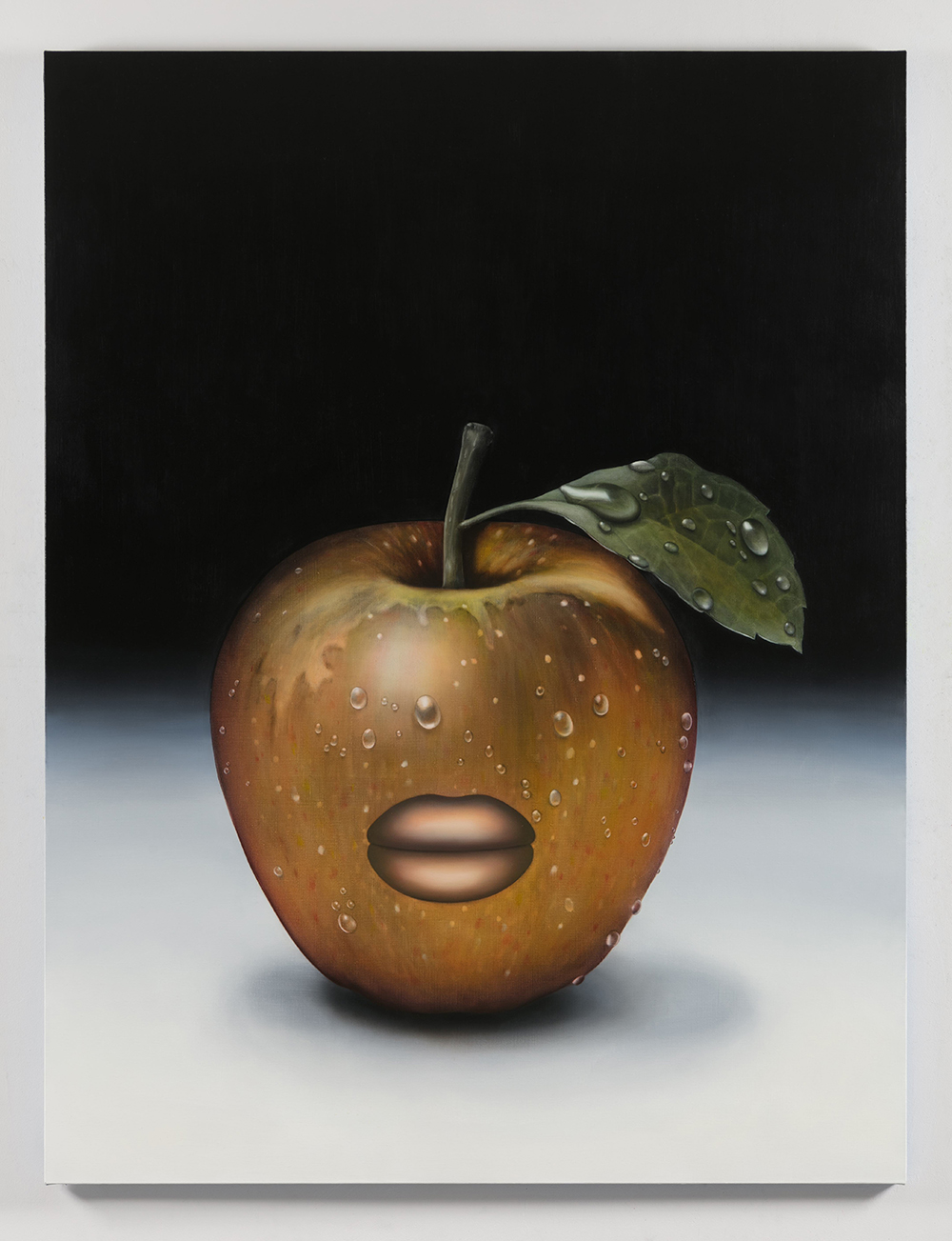

Smith has a highly distinctive aesthetic. In her early works, she experimented with a mix of watercolour and gouache on linen, mimicking the look of oil painting. This cunning façade suits her pieces, which always appear too perfect to be real. In her more recent oil paintings, bumps are smoothed out, pink sunsets are depicted in flawless gradients, and body parts assume a plastic finish.

- Left: The Studio (Broom and Mushroom), 2015. Centre: Still Life, 2015. Right: The Studio (Never Tear Us Apart), 2015

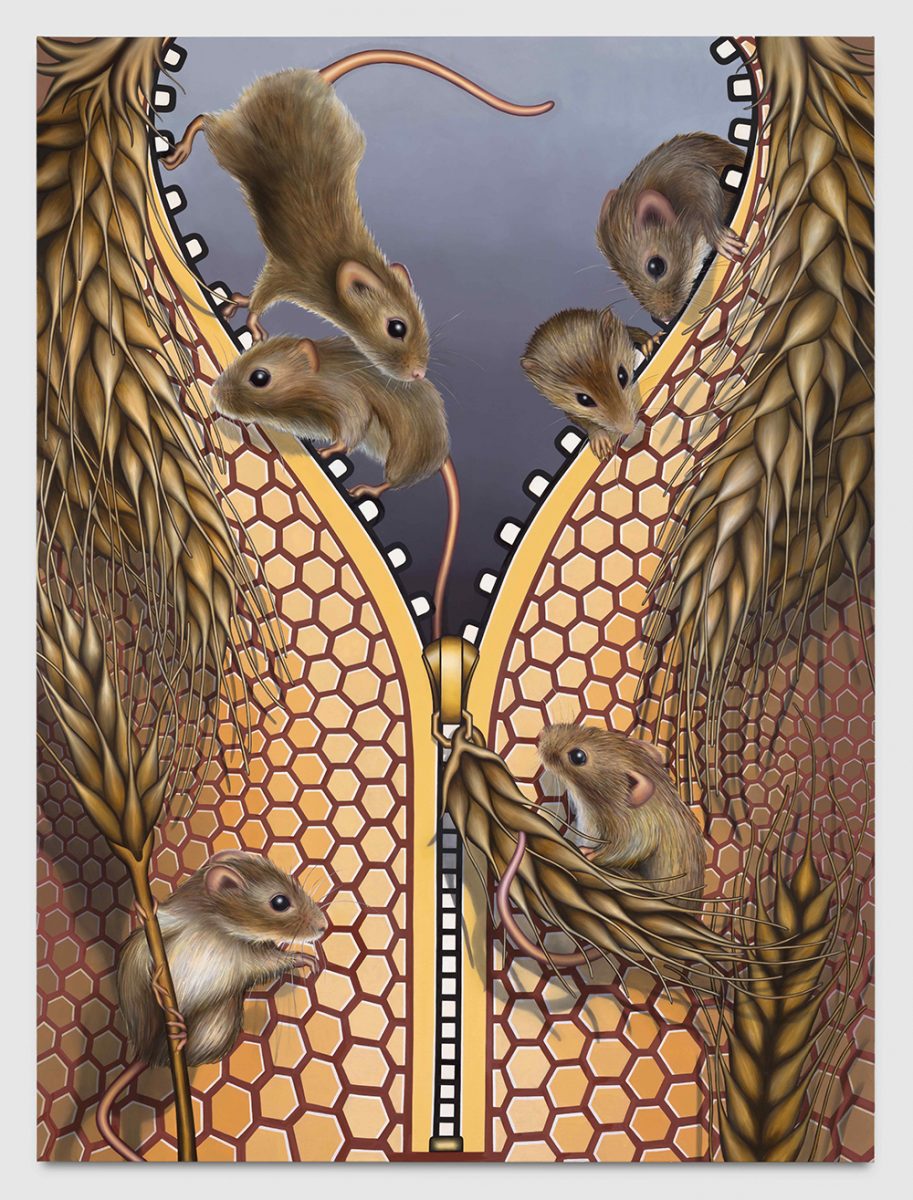

Her paintings are both playful and sinister, featuring frenzied open mouths lined with piano key teeth and a sensual depiction of temperature: ice cubes melt into puddles, beads of sweat drip down the faces of bespectacled apples, and red suns beat onto the paintings’ subjects from flawless backgrounds. There is a tension between the mess of life and the veneer of contemporary images. She doesn’t show the viewer much of the mess, but the suggestion is there that her glossy fruits will eventually rot and her maniacally grinning characters are up to no good.

“The paintings often sit within a constellation of references spanning time periods and art forms”

At first glance, her works look incredibly present-day, but this book uncovers the centuries-old references woven throughout. In one of three essays here, art historian Jenni Sorkin writes about Smith’s early use of watercolour paint, exploring the traditional understanding of the medium as “both gendered and amateur”. Sorkin also draws a connection between the artist’s use of watercolour and her mother, the amateur painter who first introduced her to the medium.

Sorkin investigates the numerous symbols and icons that repeat in Smith’s paintings, such as her suggestive banana depictions. The writer pulls together quotes from Gwen Stefani; Warhol’s banana on The Velvet Underground’s aforementioned album cover (perhaps “a metaphor for the brazen rot at the core of the Velvet’s album”); and Charlie Chaplin’s classic peel slip in By the Sea (1915).

Such detailed explorations of Smith’s key emblems offer a deeper understanding of her practice’s complex layers. The paintings often sit within a constellation of references spanning time periods and art forms. These references aren’t needed to engage with the works, but they provide satisfying undercurrents for those who want to search for them.

In another essay, art historian Suzanne Hudson places Smith’s practice within a contemporary context, noting that the artist began making work after the “death of painting” had been declared in the 1980s. She discusses Smith’s experience at Columbia on the university’s visual arts MFA in 2006, quoting Smith’s recollection that “there seemed to be a lot of suspicion about painting, as if it was too commercial and didn’t have enough to offer in the intellectual conversation. Which I of course didn’t think was true and don’t think is true today still.”

Hudson frames Smith’s practice as an interrogation of what painting can be now, while keeping a firm eye on its history. She notes Smith’s deferral from the abstract trends that dominated at the start of the 21st century, instead choosing to depict “mannequin heads and female figures dissolving into landscapes” when she first graduated. Her embrace of symbols and suggestiveness could be seen as a rejection of the “painting is dead” narrative, as she excavates and reimagines well-worn methods in her own way.

“Her paintings are both playful and sinister. There is a tension between the mess of life and the veneer of contemporary images”

The trio of essays in the book is completed by Gabriela Rangel’s take on Smith’s work, which imagines her as a 21st-century surrealist. This comes at a pivotal time when new life is being breathed into a movement that had, until recently, felt stale. The strong influence of surrealism’s women at this year’s Venice Biennale, as well as headline shows at The Peggy Guggenheim Collection and Tate Modern, are helping to define surrealism as a thriving and very contemporary movement.

- Left: The Studio (Seance), 2015; Centre: The Studio (Big Banana), 2014; Right: Ilk and Honey, 2020

Ultimately, despite the weight of history that feeds into Smith’s work, she is very much an artist of her time. Her work and career trajectory has undoubtedly benefited from the Instagram format, where bold colours, clean forms and punchy subject matter combine to create algorithmic gold. This book helps to dig a little deeper, uncovering the intricately considered framework that sits behind her all-too-perfect veneers.

Emily Steer is Elephant’s editor

Emily Mae Smith is out now (Petzel)