On the 50th anniversary of its detonation into the art establishment, the republication of Linda Nochlin’s Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? might be met with the reasonable question of “Why now?” In bringing this landmark essay back into the spotlight, one can assume that it has something to tell us about our current moment.

First published in Art News while she was teaching her Women and Art class at Vassar College, New York, Nochlin takes aim not just at the art historical hierarchy, but the environment which continued to produce such generalised, dismissive questions around women’s creative capacity—of which Nochlin’s title is the tongue-in-cheek epitome. Instead of simply rebalancing the canon by spotlighting neglected female artists, Nochlin advocated a complete reexamination of the social and economic conditions of cultural production, discourse and taste. To fully appreciate the diversity of women’s contribution, she explained, we need to dispel the “naïve idea that art is the direct, personal expression of individual emotional experience.”

The title itself is a provocation, setting off a chain reaction “to challenge the assumption that the traditional divisions of intellectual inquiry are still adequate.” In other words, Nochlin doesn’t shy away from expanding her remit beyond the world suggested by the essay’s title, which, as Catherine Grant, a senior lecturer in art and visual cultures at Goldsmiths and author of the edition’s new introduction reminds us, is a debate largely framed in the language of the oppressor.

The question “insidiously supplies its own answer,” Nochlin writes: that “there are no great women artists because women are incapable of greatness.” She dismantles this via case studies of both male and female artists, paving a daunting but hopeful path towards women’s—and indeed, everyone’s—flourishing in the arts.

Grant’s introduction gives us some clues as to Nochlin’s modern relevance. It is largely an exercise in clarification, albeit a necessary one: the development of the intellectual climate in the fifty years since first publication requires that Nochlin’s terms be revisited. “The term ‘woman artist’ is as much of a historical construction as that of the ‘great artist’” Grant writes, citing Eliza Steinbock’s research in the area of art-historical trans representation.

It might be inferred that what follows is a dated or essentialised treatment of gender—a seventies relic prompting unease for modern readers. Thanks to Nochlin’s methodology, the opposite is true. Her objective—to dismantle the idea that women’s absence from art history is predetermined by gendered characteristics—gestures towards moving beyond womanhood as biologically contingent, despite the essay’s infrequent references to anatomy.

“The development of the intellectual climate in the fifty years since first publication requires that Nochlin’s terms be revisited”

“The fault lies not in the stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces,” she writes, “but in our institutions and our education—education understood to include everything that happens to us from the moment we enter this world of meaningful symbols, signs, and signals,” she writes (with de Beauvoirian undertones). The unavailability of nude models to female artists is case in point: “as though a medical student were denied the opportunity to dissect or even examine the naked human body”. Once revealed that this lopsided art history is socially constructed, it’s a small leap that the gendered understanding on which it rests is too.

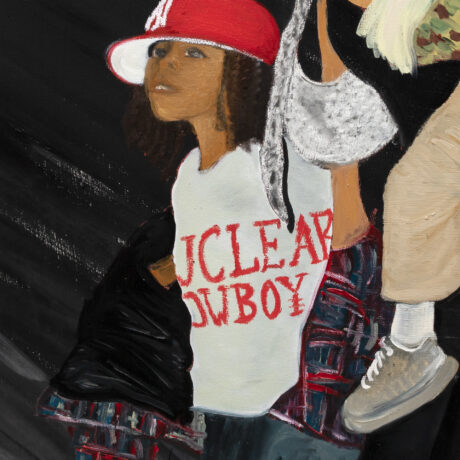

Most prescient is the essay’s use of language around equality and opportunity, resulting in what we might now call an intersectional approach. After dismissing the idea of an innately ‘female’ form of art-making, Nochlin makes clear that her method is structural: “In the arts as in a hundred other areas, things are stultifying, oppressive and discouraging to all those, women among them, who did not have the good fortune to be born white, preferably middle class and, above all, male.”

This acknowledgment of how disadvantage operates across multiple identities goes beyond what a modern observer may expect of the period. (One thinks of the contrast with the dominant cultural depiction of 1970s American equality struggles in the year preceding this reissue, Mrs America, a historical drama showing the Equal Rights Amendment being frustrated by Phyllis Schlafly, who at one point encourages white conservative women to offer state legislators homemade bread and jams in exchange for support). Nochlin refuses to shy away from class, her tone knowing and fearless throughout. “One would like to ask, for instance, from what social classes artists were most likely to come at different periods of art history, from what castes and sub-groups.”

“Most prescient is the essay’s use of language around equality and opportunity, resulting in what we might now call an intersectional approach”

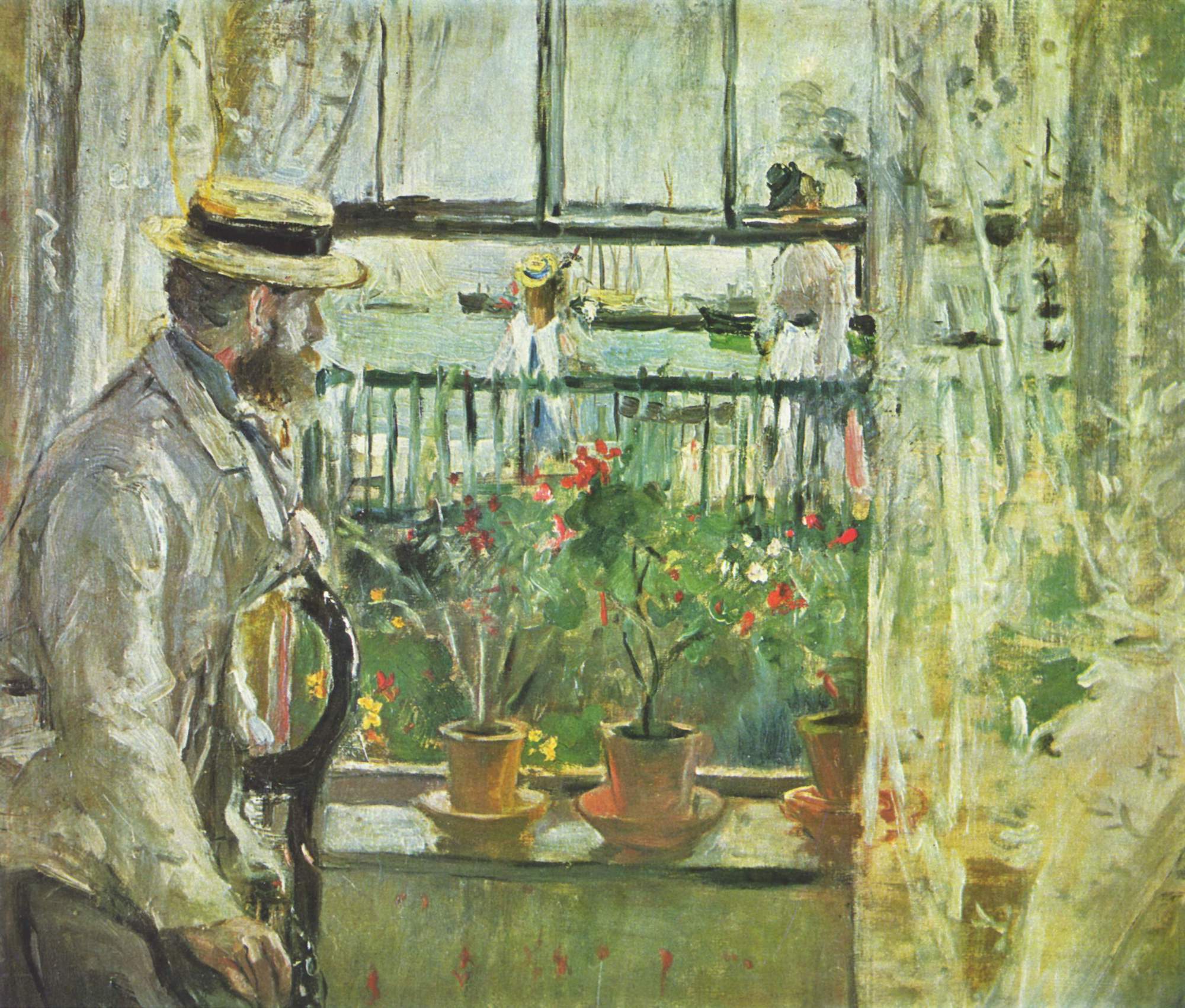

Smart too are Nochlin’s examples of successful women artists, whose advantages she reveals in order to demonstrate their exclusivity—another now-familiar technique. “We can point to a few striking characteristics of women artists generally: they all, almost without exception, were either the daughters of artist fathers, or, generally later, in the 19th and 20th centuries, had a close personal connection with a stronger or more dominant male artistic personality.” Sabina von Steinbach, Lavinia Fontana and Artemisia Gentileschi are outed in the name of the cause. The punchline follows in a case study of Rosa Bonheur, whose success, Nochlin concludes, establishes the role of institutions as a “necessary, if not sufficient cause of achievement in art.”

Progress has been slow. Nochlin recounts in Thirty Years After, 2006 (reproduced in this new volume), that in November 1970 just two out of 81 major ARTnews articles were about women; five out of 74 for Artforum. She seethes at a 2001 New York Times article in which “manly men” are heralded in the wake of 9/11: “The implications of the piece ring out loud and clear,” she says, “real men are the good guys; the rest of us are wimps and whiners—read ‘womanish’”.

“Reading Nochlin in the present moment, when the language of social justice has become so toxified, her insights feel refreshing”

There is space for celebration in this later entry: Joan Mitchell, Griselda Pollock receive the plaudits, though her admiration for Louise Bourgeois stands out—an artist whose work “is characterised by a brilliant quirkiness of conception and imagination in relation to the materiality and structure of sculpture itself.” Sam Taylor-Johnson, Pipilotti Rist, Janine Antoni are named as stars of new media artmaking.

Reading Nochlin in the present moment, when the language of social justice has become so toxified, her insights feel refreshing—a clarity which comes in part from the nonpartisan, pre-culture war context. “Those who have privileges inevitably hold on to them, and hold tight, no matter how marginal the advantage involved, until compelled to bow to superior power of one sort or another.” The effect is humbling, at times nearing a kind of modern angst as we reflect on how inconsistently these ideas have been adopted into the cultural and social psyche over five decades.

Instead of building on Nochlin’s observations, the terminology of privilege and opportunity has become a flashpoint in a new cultural battleground around representation, equality and decolonisation. “The existence of a tiny band of successful, if not great, women artists throughout history does nothing to gainsay this fact, any more than does the existence of a few superstars or token achievers among the members of any minority groups,” she concludes. One might consider in response the level of hesitation around critiques of tokenism and superficial representation in public life today, not to mention endless column inches and self-help books which advocate a variation of ‘Girlboss feminism’.

Is it burning foresight, or the lack of progress that makes Nochlin still so compelling? Her lasting goal might be the eradication of gendered classification altogether. “In every instance, women artists and writers would seem to be closer to other artists and writers of their own period and outlook than they are to each other,” she writes. Four years after her death, what would she think of her biting title being emblazoned once more over 19th century portraits, for a reading public yet to fully internalise her 50-year-old assessment? She said herself in 2015, “there is still a long way to go.” She was right—and any future map must heed her instructions.

Linda Nochlin, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?

Published by Thames & Hudson, February 2021

VISIT WEBSITE