Back in early 1980s Detroit, seventeen-year-old Juan Atkins arrived at his collegemate Rik Davis’s studio for the first time. Atkins had grown up immersed in music. He played various instruments, including bass guitar in a local funk band, and his father was a nightlife promoter—but this was a different kind of realm. Atkins described it as “like walking into a spaceship”. Decades on, as a globally renowned techno pioneer, he recalls this creative launchpad.

“In those days, I only had my Korg MS-10 [an iconic late-seventies synth] in my bedroom; Rik had a whole room of gear,” Atkins tells me, cheerfully. “The lights were off, the shades were down, and all you could see were these LED lights flickering. It felt like I was travelling through a portal into a different zone. I felt like I was stepping into the future.”

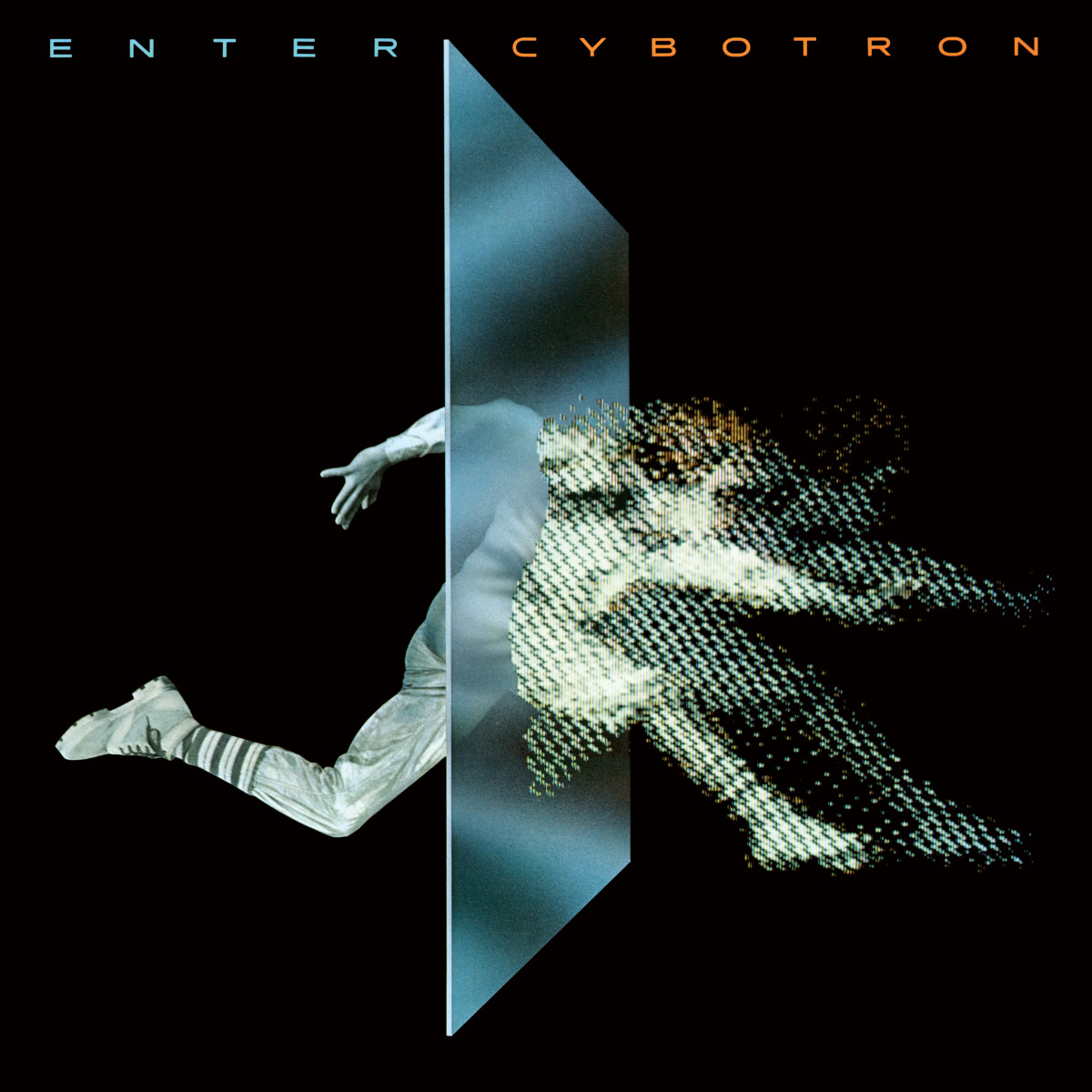

Atkins and Davis would forge a brief yet brilliant bond as Cybotron, creating electronic music that vividly evoked the futuristic, otherworldly atmospheres Davis’s “spaceship” studio promised. Cybotron tracks such as the 1981 debut Alleys of Your Mind, the thrillingly urgent Clear (1983; sampled by Missy Elliott for her 2005 single Lose Control), Cosmic Cars and Techno City were instrumental in shaping the sinewy, soulful Detroit techno sound, and they somehow still sound ultra-fresh in the real-life digital age. Although the duo parted ways in 1985 (Davis favoured rockier styles, and developed his 3070 guise), Atkins kept the Cybotron machine pulsing (along with various other monikers including Model 500 and Infiniti), and became recognized as one of Detroit techno’s core innovators, alongside neighbourhood cohorts Kevin Saunderson and Derrick May, aka the Belleville Three. Cybotron’s debut live shows—launching tomorrow at London’s Barbican Centre, and described as “a symbiotic journey through sound and light” with visual collaborators Pilot—have been a very long time coming, but perhaps twenty-first-century tech is finally catching up with this genre’s future visions.

“A computer can be as good, if not better than a person when collaborating with music”

“When I create, I think I’m just a vessel, to get these sounds to earth,” says Atkins. “I love sci-fi, and I do have a picture in my mind, and that’s what I’m creating soundtracks for.” He’s also a firm believer in a powerful bassline: “There’s something about lower frequencies that make you move and have more effect on your body, mind and soul.”

The Cybotron live show is rooted in the principle that “a computer can be as good, if not better than a person when collaborating with music”, and presents seminal material alongside new album tracks. It also promises the most ambitious visuals to date from Pilot (who have previously worked with superstar DJs including Fatboy Slim and David Guetta); their specially coded tech generates images in response to Cybotron’s live music. It’s intriguing that this live debut is in a seated concert hall rather than a sweaty club, but it also brings to mind electronic artists turned sophisticated tech designers such as Robert Henke, who has constantly refined the “audio-visual stimulation” of his Lumiere live show.

“Our technology brings together audio/lasers/lights/LED/video into the same control interface that allows revolutionary new ways of working between the media,” explains Pilot’s Ben Brett. “For Cybotron Live, we have designed a bespoke system that allows Juan to send multi stems of live audio (a total of seventeen in his case) into the Pilot digital audio workstation, which in turn interact with the LEDs and lasers in real-time. Sound frequencies sent from Cybotron to the Pilot system are configured in such a way that the music generates a visual synergy/language of its own.”

Techno music has numerous pulse points in world cities across Germany (home of Mensch Maschine pioneers Kraftwerk, whose electronic sound and robo-doppelgangers heavily influenced these clubbier expressions); the Netherlands; Britain; America and beyond—but Detroit ultimately feels like its spiritual home. The urban backdrop of this “Motor City”, the rise and crash of its car industry (and mechanical production lines), and its rich musical heritage (spanning Motown to garage rock and hip hop) all seem to filter into Detroit techno’s rhythms, and the futuristic images they summon.

The passion for sci-fi and space-age cities echoes throughout most of Detroit techno labels and monikers, such as Atkins’s Metroplex records, Derrick May’s Transmat and Planet E Communications (founded by Detroit DJ/producer Carl Craig); the more political approach of city collectives like Underground Resistance (originally founded by Jeff Mills, “Mad” Mike Banks and Robert Hood in 1989) also applied an out-there energy to their dystopian tracks and bold artwork. Mills later took his own interest in sci-fi further by composing techno soundtracks to classic movies such as Fritz Lang’s 1927 opus Metropolis (when I watched Mills perform this live, the crowds of ravers cheered wildly for the film’s legendary android Maria, every time she appeared on screen) and 1965’s Fantastic Voyage.

“There’s always been this very delicate interface between man and machine, organic and digital”

- Abdul Qadim Haqq, (left) Model 500, 1993; (right) Galaxy 2 Galaxy, 2006

Many of the above labels and associated acts have also featured the gloriously florid robo-reveries of visual artists such as Abdul Qadim Haqq (founder of Third Earth Visual Arts) and Alan Oldham, whose works draw from inspirations including Afro-futurism, cyberpunk, Japanese anime and time travel. Pioneering VJ Dvdan seized on emerging nineties visual tech to accompany Detroit techno sounds, while sculptor/photographer M Scott Johnson took formative inspiration for his Afro-futurist works as a young clubber in Detroit. Johnson told the Atlanta Black Star: “I was always wondering: What’s the visual response to techno for African American artists? In techno, the undulation of the line is like a repetition of the beat, so there’s an over exaggeration that allows you to interpret the music in a very abstract way—similar to how artists translate hip hop into graffiti writing.”

- (Left) Matthew and Richie Hawtin unpacking. Image by Kasia Zacharko (right) F.U.S.E. Matthew and Richie Hawtin, The Building, Windsor, Canada, 2018

Meanwhile in London, a new multimedia exhibition from techno musician/painter siblings Richie and Matthew Hawtin ties in with the twenty-fifth anniversary reissue of the seminal Dimension Intrusions album released under Richie’s Fuse guise. The vivid hues of Matthew’s original 1993 canvases seem to blaze into the dark gallery space; their abstract shapes have a three-dimensional quality which he would further explore in his recent Torqued paintings series. Richie Hawtin would prove a techno trailblazer (with further famous guises including Plastikman) with increasingly intricate live sets; these early compositions borrowed futuristic titles from his brother’s paintings—including Computer Space, and previously unreleased works now throb through the gallery speakers.

“There’s always been this very delicate interface between man and machine, organic and digital,” says the genial Richie. “Back then, everything was in our imaginations. Matthew was painting the future; I was sculpting it sonically… how do you picture the future, now that techno music has a history, and you’re living in the future that you used to imagine? Standing in the room, it gives me confidence to go back to that original point of innocence, and just create.”

Detroit transmitted its irresistible influence, though the Hawtins had a unique vantage point, as Matthew explains. “We lived in the border city of Windsor, Canada, but we would go clubbing in Detroit, so we got to be insiders and outsiders. At that time, Windsor and Detroit were the automotive capitals of their countries; we had electronics at home (the Hawtins’ dad was a robotics technician) and factories around, but there was a vastness in the landscape as well. When I look at our works, I can sense that.”

“We would go into a virtual space, into Detroit—crossing the border was like a transition,” agrees Richie. “There would be huge spaces between these empty skyscrapers: not dense like London or New York. We’d find warehouses where we’d have parties; there was this sense of space and grandeur. I remember we’d listen to my demos, driving through the highways of Detroit, looping around and coming back into ‘Techno City’. Then we would go back to our studio in Windsor, and driving back, you have this classic shot of Detroit. We’d look out into the fishbowl that we’d just experienced, then go back into the studio and imagine it. The architecture that we inhabited during those pivotal moments is totally evident visually and sonically in our work.”

There is somehow something timeless about these future sounds and visions; human impulses surge through wires and processors, and the metropolis stretches before us: neon-lit, seemingly infinite.