To visit London without taking a trip on the Underground is to bypass a quintessential part of the city. The Tube, as it has been known for over a century, is a vast subterranean borough of its own, stretching out from the heart of Westminster to the far-flung reaches of the outer suburbs. The oldest underground railway in the world—it commenced in 1863 with the Metropolitan Railway, the first of several privately-owned lines that were marshalled into one network in 1933—the Tube’s blue-and-red roundel and Johnston font rank high among the city’s visual identity. What fewer visitors know, though, is that it also serves as an art gallery of sorts deep beneath the ground.

There are grander rapid transit systems. The Tube is not so lavish as the ballrooms of the people beneath Moscow and St. Petersburg, or so miraculous as Stockholm’s organic, cave-like atriums that accentuate their location in the bowels of the Earth. And there are no stations as bizarre as Naples’ surrealistic Toledo or the Paris Metro’s steampunk Arts et Métiers. But—much like the city above ground—what the Underground has in abundance is variance and quirk, with a series of models subjected to endless peculiarities. Some, such as Ervin Bossányi’s heraldic stained glass windows (1938) at Uxbridge, crown their station’s aesthetic; others, such as Harold Slater’s 1930s tiles depicting London architecture at Aldgate East, are quieter interventions that even regular users pass by.

“There are grander rapid transit systems. But—much like the city above—what the Underground has in abundance is variance and quirk”

The 1930s were the first golden age of art on the Tube, much of it due to the efforts of commercial manager (and later London Passenger Transport Board CEO) Frank Pick. There was design on the Tube beforehand. In the 1900s the architect Leslie Green had clad numerous stations in ox-blood terracotta, sometimes with Arts and Crafts-inspired tiles topped with acanthus leaves and pomegranate designs inside.

But it was Pick that pushed for the idea of a system with a unified visual identity. He had the architect Charles Holden design a series of modernist stations, the draughtsman Harry Beck plan the streamlined, topological tube map, and employed the typographer Edward Johnston to create the famed roundel and typeface. He fully embraced the promotional pull of graphic art, with extraordinarily kinetic linocuts by the duo of Sybil Andrews and Cyril Power

.

- Jacob Epstein, Day and Night, 1929 at 55 Broadway

Above ground at 55 Broadway, Transport for London’s towering headquarters above St James’s Park station, he employed a set of contemporary sculptors including Henry Moore, Eric Gill and most prominently Jacob Epstein, whose statues Day and Night (1929) offended a prudish public due to the former’s nudity; as a compromise, Epstein agreed to chop off an inch of penis to placate his detractors. In 1940, shortly before his retirement, Pick had the sculptor Eric Aumonier install a statue of an archer outside suburban East Finchley station. Its bow still points straight down towards the city, in the direction of the northern line.

The Second World War and the austere period that followed curtailed such grand artistic gestures for some decades. When it re-emerged, it did so in the inexpensive form that characterizes the Tube’s aesthetic more than anything else: tiles. Each stop on the high-speed Victoria Line, which was opened between 1968 and 1971, saw an artist create mosaics capturing that station’s identity. Positioned behind wooden benches along the platform walls, these included the now-lost neoclassical Euston Arch for Euston, a geometric swan for Stockwell (after the adjacent Swan pub) and, in a punning move, a literal ton of bricks for Brixton. Of particular interest to artistically-inclined visitors is the op-artist Peter Sedgley’s abstract yellow spots, representing the modern art then to be found at the nearby Tate Britain.

The 1980s saw this tiling grow more ambitious. At Finsbury Park’s southbound Piccadilly line platform, Annabel Grey installed a set of six vintage hot air balloons, in a mistaken reference to Finsbury Fields, a now-lost open space some 3.5 miles to the south where Britain’s first hot air balloon launch took place. Pressed against the curved platform walls, they can be hurriedly walked past without notice.

“Each stop on the Victoria Line saw an artist create mosaics capturing that station’s identity”

More unavoidable are Eduardo Paolozzi’s eccentric mosaics at Tottenham Court Road. Completed in 1986, they once covered the 950 square meetings of the station, though recent expansion work has seen a fraction removed to Edinburgh. Resembling the Scottish pop artist’s busy, dense screen prints, they combine abstract forms with disparate objects including cameras, saxophones and butterflies. They have long-divided Londoners: are they a jubilant paean to urban existence or a garish po-mo relic? Restored in 2017 after accruing decades of grime, they now sparkle with a new lease of life.

In 2000, the Underground was brought under the aegis of Transport for London, and the network was integrated with other light railway services such as the Overground and the Docklands Light Railway. That year the new organisation created Platform for Art, a dedicated programme of contemporary art. Now known by the less oblique name of Art on the Underground, it has ushered in an unprecedented variety of artistic projects, with both permanent additions and temporary showcases.

Its most ambitious schemes have seen artworks extend across the entire tube map. Mark Wallinger’s Labyrinth (2013), which was convened to celebrate the Tube’s 150th anniversary, consists of panels depicting circular mazes. All 270 stations feature one, positioned alternatively in more and less obvious positions. Finding them all is a task for only a devoted few.

Tiles have continued to be a feature into the new century. Since 2001, the corridor leading into Leytonstone station has been enlivened with fourteen figurative mosaics depicting the life and films of the locally-born Alfred Hitchcock. Designed by the Greenwich Mural Workshop and commissioned by the area’s local council, they bring commuters in daily contact with such traumatic schemes as Psycho’s shower murder and The Birds’ avian attacks.

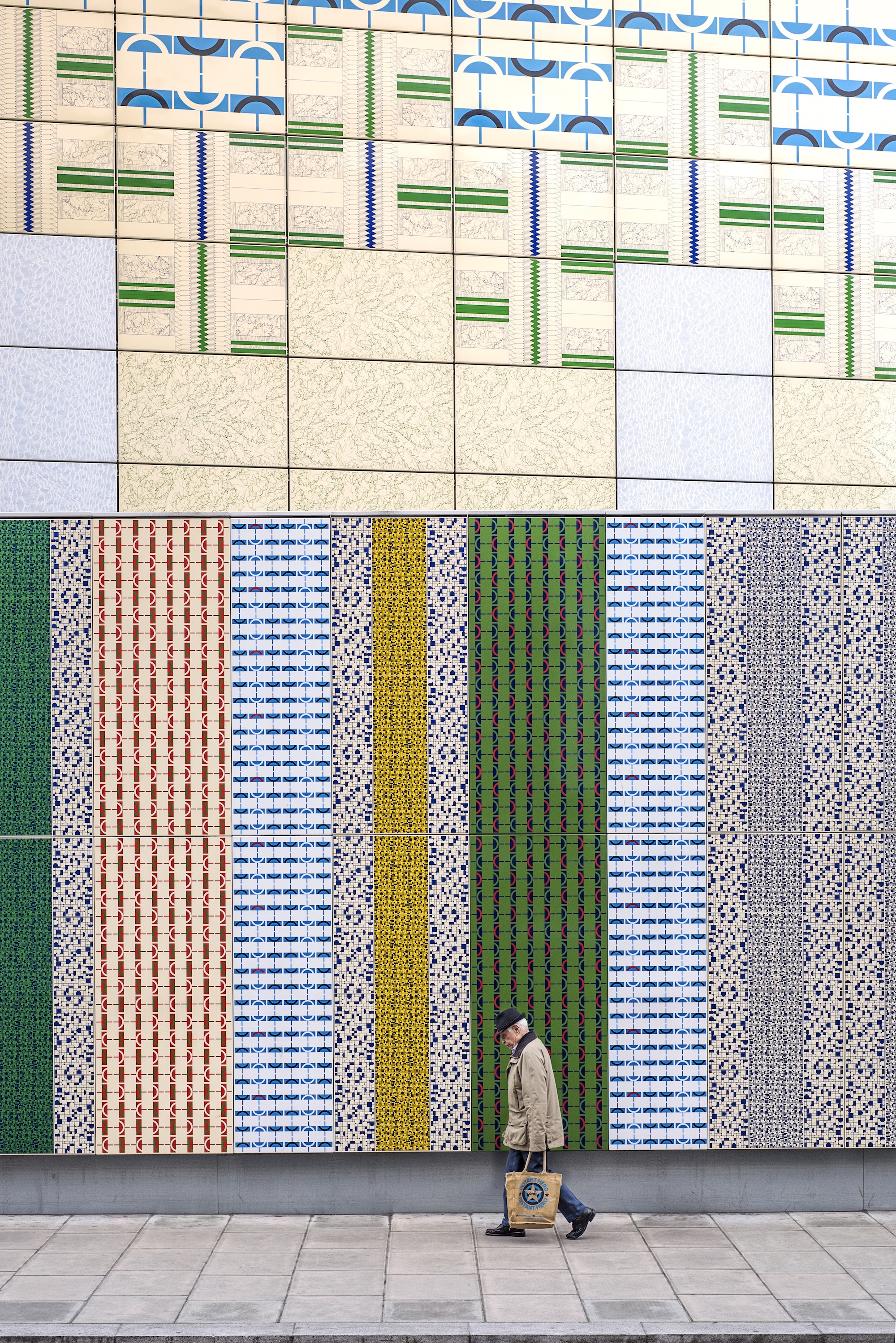

More recent mosaics include Michael Craig-Martin’s Street Life (2009) at the DLR station Woolwich Arsenal, which gathers together the block-coloured household objects of the artist’s paintings in a lively dance, and Giles Round’s Design World Leisure (2016) on several Victoria line stations, a reimagining of interwar Tube design motifs arranged in astringent patterns.

“Eduardo Paolozzi’s murals have long-divided Londoners: are they a jubilant paean to urban existence or a garish po-mo relic?”

- Daniel Buren, Diamonds and Circles at Tottenham Court Road Station

Perhaps because of the mixed reaction that greeted Paolozzi’s in-your-face contribution, this new era of permanent artworks within the stations has stuck to the subdued and the abstract, which contrast with the largely photographic advertisements sprawled across most station elevators and platforms. At Tottenham Court Road, Diamonds and Circles (2017) by Daniel Buren comprises a series of panels with simple geometric shapes in bold colours above a black-and-white striped background. Full Circle (2009-11) by Knut Henrik Henriksen at King’s Cross St Pancras is subtler still, with two semi-circular steel panels that appear to blend into the walls behind them.

Station exteriors do present a canvas for busier works, however: Jacqueline Poncelet’s Wrapper (2012) turns an external wall of Edgware Road into a rainbow of tessellating patterns on vitreous enamel, chosen after three years consultation with residents of the district.

Art on the Underground’s temporary programme has allowed for the sort of large-scale works that, if permanent, might be deemed an imposition on a functional space. Few who encountered it will forget Heather Phillipson’s My Name is Lettie Eggsyrub (2018-2019) in a hurry, a berserk egg-themed multimedia installation that spanned an entire disused platform at Gloucester Road.

A series launched last year has seen a vast panel above Brixton station’s entrance adorned with large-scale paintings that engage with its area’s multicultural community. First up was Njideka Akunyili Crosby, who depicted a Windrush generation family, followed by Aliza Nisenbaum’s group portrait of station staff. During Frieze this year, the wall will be given to the painter Denzil Forrester, who will reinterpret his earlier work Three Wicked Men (1982), which presents a policemen, a political and a businessman along with his friend Winston Rose, who died while being restrained by police in 1981.

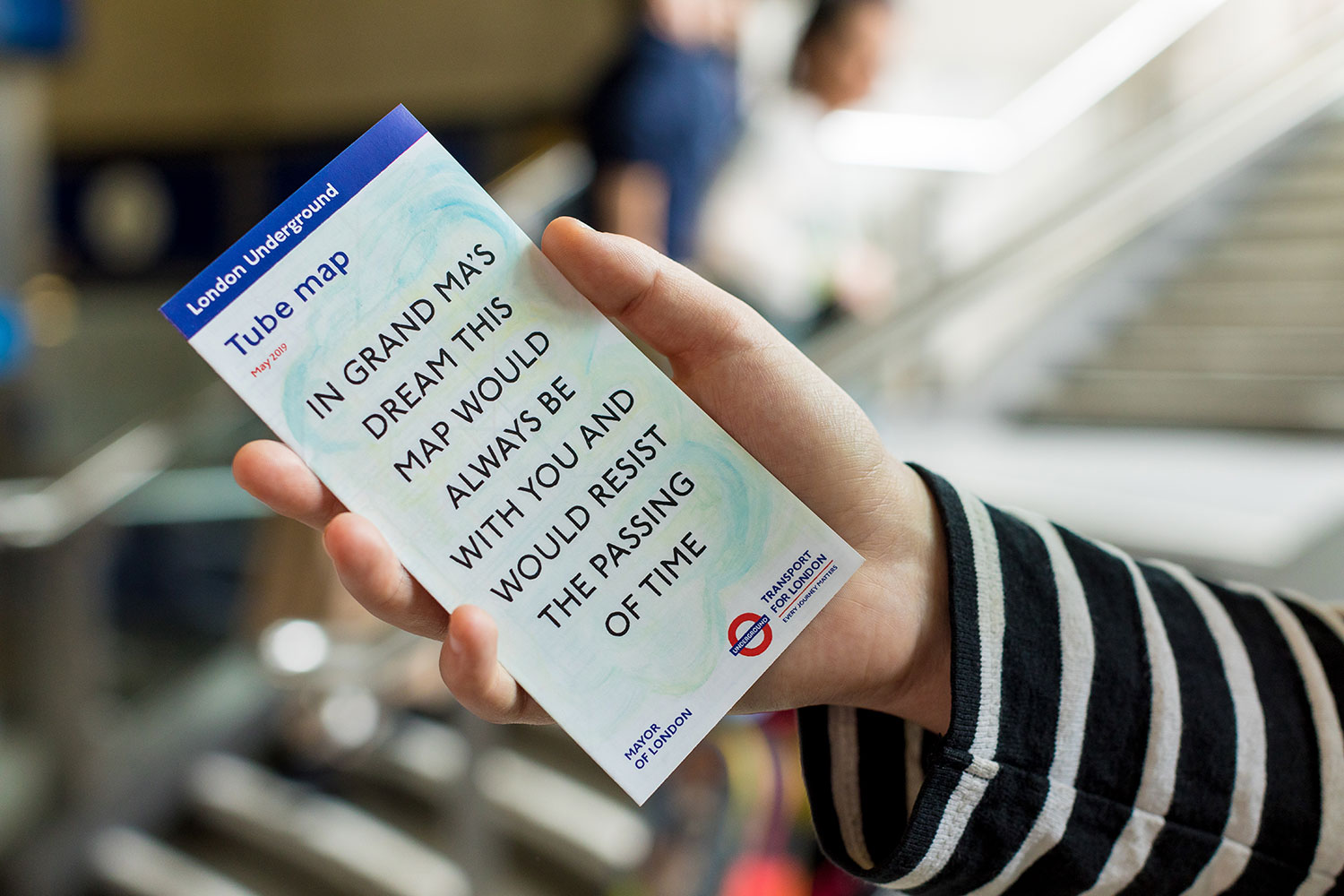

The other major temporary project running this autumn is Laure Prouvost’s You Are Deeper Than What You Think (2019), a series of text art posters spread across the network. Her work extends to cover of the pocket map available at all stations, where it joins a line of portable, ephemeral works. Running since 2004, this scheme has seen a diverse range of responses, including an I Ching-influenced grid by Richard Long, a Rorschach mark-esque blotch by Cornelia Parker, and recently a collaged image of a pair of lips being pushed into another from Linder

.

The twenty-four-hour weekend Night Tube, which launched in 2016, has its own series of map artworks. The current iteration, by Jade Montserrat, is based on a pencil and watercolour drawing that connects with the artist’s ongoing project of challenging Britain’s structural racism.

“The super-abundance of projects in recent years suggest that the Underground has entered a second golden age of public art”

The super-abundance of projects in recent years suggest that the Underground has entered a second golden age of public art. 2019 will be seen out with new pieces from Larry Achiampong, Nina Wakeford and Bedwyr Williams, while Alexandre da Cunha and Samara Scott have been commissioned to create permanent works for the stations of the new Northern Line extension, which opens in 2021. Artists commissioned for stations on the controversially delayed new Elizabeth Line include Yayoi Kusama, Chantal Joffe and Darren Almond.

In a city whose art world largely hides behind the walls of museums and galleries, the Underground represents somewhere where art and design thrums in the background of everyday London life. For visitors who want to experience art unique to the city—and that exists and ages alongside the lives of residents—you could do far worse than spend some time exploring its tubular underbelly.

All images courtesy Transport for London and Art on the Underground

Spotlight on London

Our five-part series explores the British capital and its creative communities.

EXPLORE THE SERIES