The hashtag #HilmaAfKlint has been used on Instagram 34,611 times. That is more than both #BridgetRiley (18.2K) and #SoniaDelaunay (17.3K), but less than #JacksonPollock (151K). Under Hilma Af Klint’s hashtag, you will find fashion items directly inspired by her colourful paintings, nail art which scales her motifs down to miniature form and jewellery that re-interprets these geometric shapes. Selfies in front of her paintings abound (they are currently on display at the Guggenheim in New York, as part of her first major solo exhibition in the United States), while others pose with prints of her work at home. Captions read along the lines of, “Feeling all sorts of spiritual”; “Today I worshipped at the altar of Hilma Af Klint”; and, “I think that Hilma and I would have been friends”.

It might seem surprising that an obscure artist, who was born in 1862 in Stockholm and died in 1944, could elicit such emotion more than 150 years after their arrival in this world. But Af Klint’s remarkable story, involving spiritualism and fierce modesty (her instructions for her work to be kept sealed until twenty years after her death are frequently cited), has become a crucial part of the personal mythology that has been built up around her. Her late embrace from the margins of art history has only added to the mystery and against-the-odds triumph of her work, in a narrative arc not dissimilar to that afforded to outsider artists.

Af Klint herself, however, was far from an outsider artist. She graduated from Stockholm’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1887 and quickly established herself as a respected painter, serving briefly as secretary of the Association of Swedish Women Artists. She also became deeply involved in spiritualism and Theosophy, which were popular in literary and artistic circles as many sought to reconcile long-held religious beliefs with scientific advances. Her first abstract works grew out of these belief systems, in an attempt to articulate mystical views of reality.

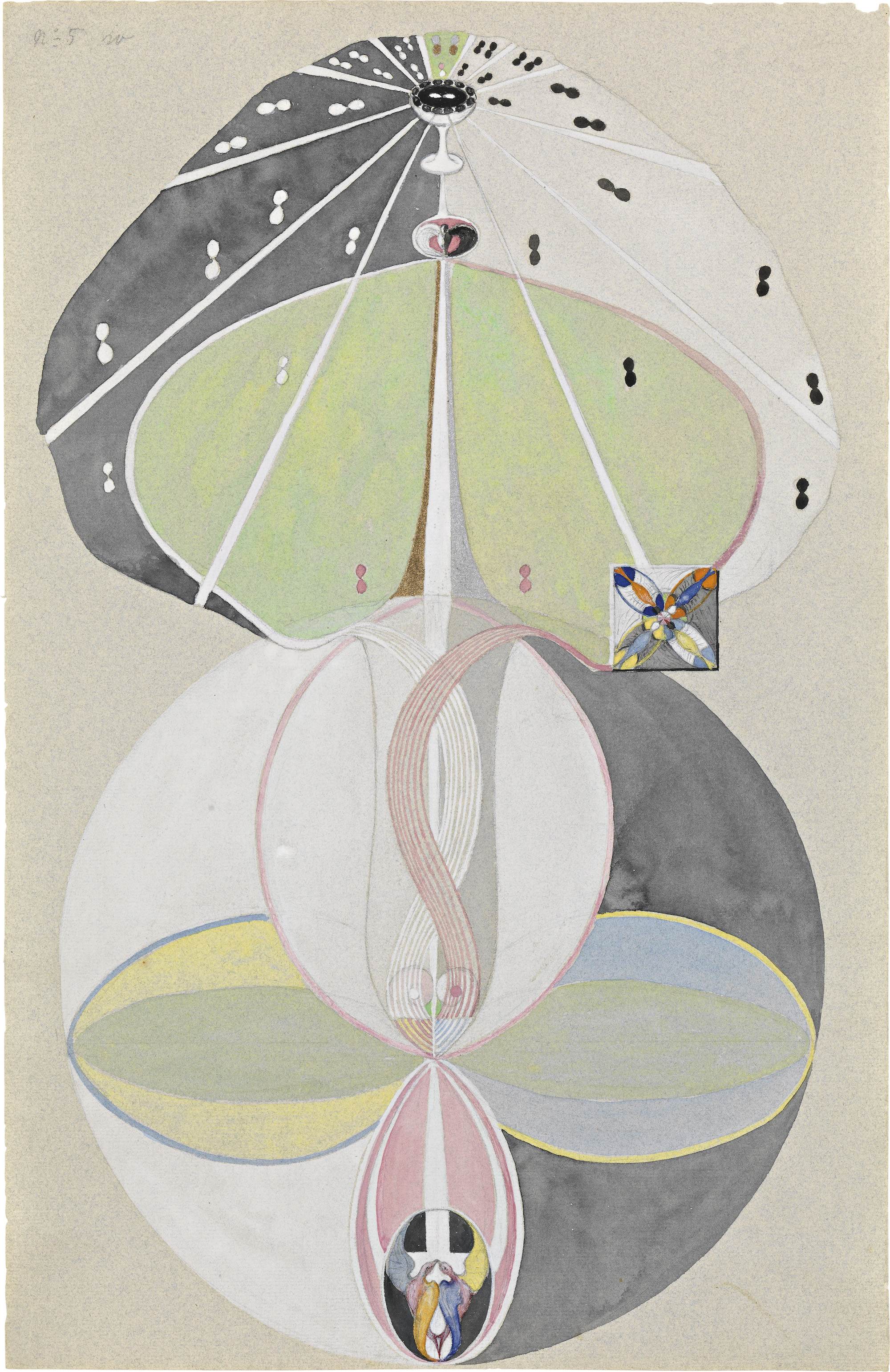

The biomorphic and geometric forms that recur in these paintings, on both expansive and intimate scales, reveal a strikingly prescient approach to composition and colour. They are suggestive of artists such as Agnes Martin and Victor Vasarely, as well as Bridget Riley and Sonia Delaunay, all of whom were working decades after Af Klint set out on her early spiritual investigations in painting. But beyond the art world, these works speak to a broader graphic design sensibility, and an immensely modern understanding of visual communication and branding.

“They have a sense of order to them that’s disrupted and energized by the hand, in the way that a lot of design work did throughout the twentieth century, and particularly in mid-century examples, like Saul Bass, Alexander Girard, Paul Rand, Elaine Lustig Cohen and earlier examples like Elizabeth Friedlander, Anni Albers (in the more expanded field of design) and Willem Sandberg,” art and design journalist Billie Muraben muses. But why are the simple shapes used by Af Klint (and many in the Bauhaus and various mid-century design movements) quite so visually pleasing and satisfying, even to this day? “I think there’s something in the balance between order/chaos, information/interpretation, in representations of geometric shapes being expressed or worked out by the human hand that’s just totally fascinating.”

“Beyond the art world, these works speak to a broader graphic design sensibility, and an immensely modern understanding of visual communication and branding”

A large part of Hilma Af Klint’s appeal is rooted in her ability to transcend scale. Whether working on a two-metre wide canvas or a small drawing on paper, the cohesion and clarity of her composition and ideas remain consistent. “In terms of graphic design and advertising, logos and insignia will generally be designed to read at a variety of scales, close up and from a distance—particularly in the case of design for transport (whether it’s cars, trains, planes, ferries), both for the sake of brand recognition and visibility, and as a sort of graphic shorthand and tool of communication,” Muraben adds.

“Those vectors are the precursor of large-scale graphics and came about with the advent of technology. She’s playing with mathematics,” says graphic designer Ana Grigorovici, who works mainly on branding for clients in art and tech. “One of the paintings with concentric circles, it does remind me of maps, tubes and systems, which are branding in a generic form—they’re basically a system to understand what you’re looking at. I’ve never seen one in real life and I didn’t realize they were so big, to me they were A4 or so.”

“A good contemporary example of this is Camille Walala, she does takeovers of streets with Memphis-style visuals. She does big large scale installations, but if you look at her sketchbooks, they’re exactly the same. She has a sensibility for large scale, and they work with vectors,” she continues. This applies also to the smartphone-sized scale that even Af Klint’s largest paintings are now frequently viewed at with the rise of social media. A new generation has become aware of her work in this way, many of whom have never actually seen a painting by Hilma Af Klint in real life. If we know anything about Instagram, it’s that seeing something on a screen rather than IRL never stopped anyone from embracing it in full. Figures from the worlds of art and culture, particularly those who are not yet considered “too obvious”, are increasingly shared with a reverence akin to brand allegiance.

- Left: No. 2a, The Current Standpoint of the Mahatmas (Nr 2a, Mahatmernas nuvarande ståndpunkt), 1920 from Series II (Serie II). Courtesy The Hilma af Klint Foundation, Stockholm; Right: Group I, Primordial Chaos, No. 16 (Grupp 1, Urkaos, nr 16), 1906-1907 from The WU/Rose Series (Serie WU/Rosen). Courtesy The Hilma af Klint Foundation, Stockholm

“Undoubtedly, Af Klint’s recent reputation amongst young, digital-savvy women in particular has been bolstered by her immersion in mysticism and the occult”

There is also something be said for the easy visual appeal of Af Klint’s work, which translates well to an image-led platform like Instagram. “In regards to Instagram likes, I think her success has something to do with immediacy, both in terms of your ability to ‘read’ the image and how that ties in to the nature of scrolling,” Muraben argues. While Af Klint’s story is a fascinating one, even those who know near-nothing about her will not find themselves left out of the party, as her paintings are able to appeal on a purely visual level. “It’s perfection and symmetry, which is more to do with the instinct and how that translates to emotion,” suggests Grigorovici.

Undoubtedly, Af Klint’s recent reputation amongst young, digital-savvy women in particular has been bolstered by her immersion in mysticism and the occult. With a group of likeminded women dubbed The Five, she engaged in the paranormal and regularly organized spiritistic séances. They recorded a completely new system of mystical thoughts in the form of messages from higher spirits, called The High Masters. As part of this, Af Klint created experimental automatic drawings as early as 1896, and believed her hand to be guided by otherworldly forces.

In January 2018, the New York Times published an article titled “How Astrology Took Over the Internet”, while the Atlantic published a piece in the same month titled “The New Age of Astrology”. Both argued that in a stressful, data-driven era, many young people find comfort and insight in the zodiac—even if they don’t exactly believe in it. The New York Times observed, “Old-school astrological images of constellations and line-drawn star signs have been replaced by pastel illustrations and mixed media collages. The dominant look is nostalgic but not staid. The rise of astrology, Instagrammable crystals and generalized coven-talk all evokes a throwback for ’90s kids, who grew up watching The Craft and playing with cardboard Hasbro Ouija boards at slumber parties.”

This zeitgeist for the paranormal and other external forces chimes with Af Klint’s own interests. The imagery that recurs in her paintings can be seen to resonate also with the pictorial nature and spiritual engagement of tarot cards. The Rider-Waite tarot deck (originally published 1910), one of the most popular tarot decks in use today in the English-speaking world, was created by another female artist who was little-known during her lifetime. Her name was Pamela Colman Smith, and it is her hand that shaped the tarot cards and associated imagery that we most commonly recognize today. These, too, have been experiencing a resurgence in recent months. An article in the New Statesman ran last August with the headline “Why Millennials Are Looking for Meaning in Tarot Cards”.

It would seem that the Guggenheim could not have chosen a better moment to exhibit Hilma Af Klint, particularly when social media engagement has never been more important to galleries and institutions internationally. Through Instagram, galleries are able to reach audiences far beyond those who will ever set foot in their exhibitions.

Meanwhile, the Serpentine Gallery (who showed an exhibition of Hilma Af Klint back in 2017) has just opened the first UK solo exhibition of Emma Kunz, a Swiss artist and healer who lived from 1892 to 1963, and believed she had telepathic and extra-sensory powers. Its title, Visionary Drawings, is reminiscent of the Guggenheim’s titling of the Af Klint exhibition, Paintings for the Future. Both demonstrate a desire to align these artists with a younger, new generation; they are also reflective of the remarkably prescient nature of their work, which seems to have finally found its time in the here and now.