Photographer James Dean Diamond has a combined fascination with science, music and technology, all of which play into a practice that favours extensive research, excessive multiple exposures and fastidious post-production. His images slide between dreamy and hallucinogenic, capturing expanses of time on city streets or commuter bridges that seem impossible to quantify. At first his densely packed black-and-white layers seem impenetrable, but the harder you look, the more visual signifiers reveal themselves. Splintered criss-crossing lines allude to high rises and glass façades, while a single street lamp transmogrifies into blazing clusters of balled light.

Your analogue, multiple-exposure process is almost unfathomable to people who are used to the quick-shot digital systems. Can you explain how you create these images, and how you go about selecting and preparing to shoot your subject?

My practice is defined by large-scale photographic journeys of nonlinear narratives; time is a critical component for the form to take shape. As such, I approach my work with a three-stage methodology:

One: Research a concept that I find of interest, one which may have the potential latitude for an in-depth investigation; Two: Test various techniques using film and digital capture, as well as experiment with a range of aesthetics until a visual language emerges to convey the premise of the project. My preference is to produce the work “in-camera”—the less time on the computer the better; Three: I travel through a number of cities searching for areas and situations that may provide suitable material.

“The pieces make reference to a painterly practice, by way of constructing alternate realities”

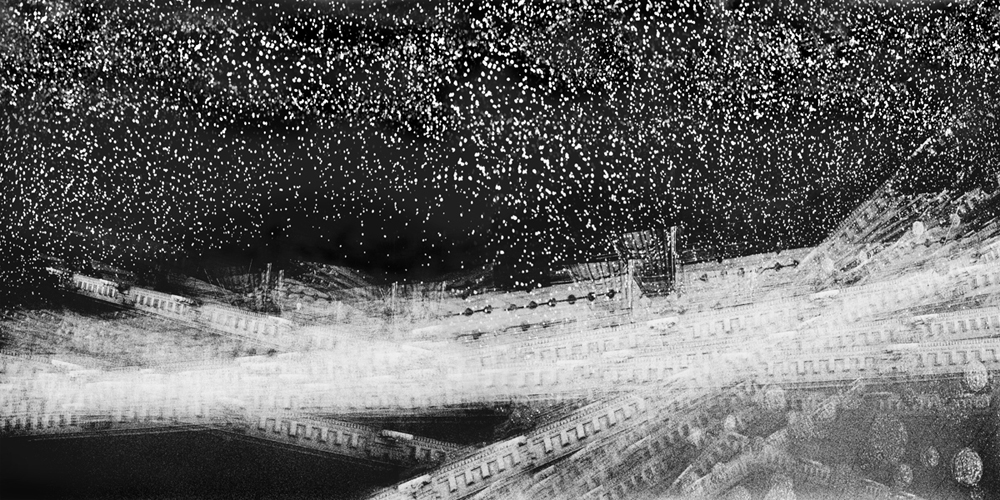

Shooting in London or Europe, the process begins by assessing the surroundings, in order to calculate the distribution of light from each surface. The camera is repositioned, slowing with multiple exposures, and structures, constructions, surfaces, space and scale are overlaid to make a unified composition. I make ongoing adjustments to the camera setting, along with decisions of how to move the camera through the urban environment. The intention is to build layers of gestural abstraction, where the pieces make reference to a painterly practice, by way of constructing alternate realities. The composer Conall Gleeson described this process as “action photography”, a fifty per cent calculation plus a fifty per cent chance element, where the fluctuation between the two poles exists.

As to how I select a scene, this is an unpredictable science —guided in part by instinct, in part by experience. The artist Paul Klee referred to his method as an “active line”, which increased over time with knowledge and the continuation of making work. This philosophy resonates with me enormously. When immersed within a shoot, I am completely in “the zone”, the creation of the work almost develops into a meditative plane. The artwork becomes a state of mind, rather than a state of place. Here, photography functions on both perceptive and observational levels.

How does your interest in the field of oneirology play into your practice?

On most nights I tend to dream vividly, so a project about dreams was inevitable. Recalling a particular reverie: I am in a vast derelict brick and crystal cathedral—this causes great excitement, I reach for my camera, start shooting and then wake up, feeling a little disappointed. My dreams act as a useful image source, so I keep an eye out for a vast brick and crystal cathedral!

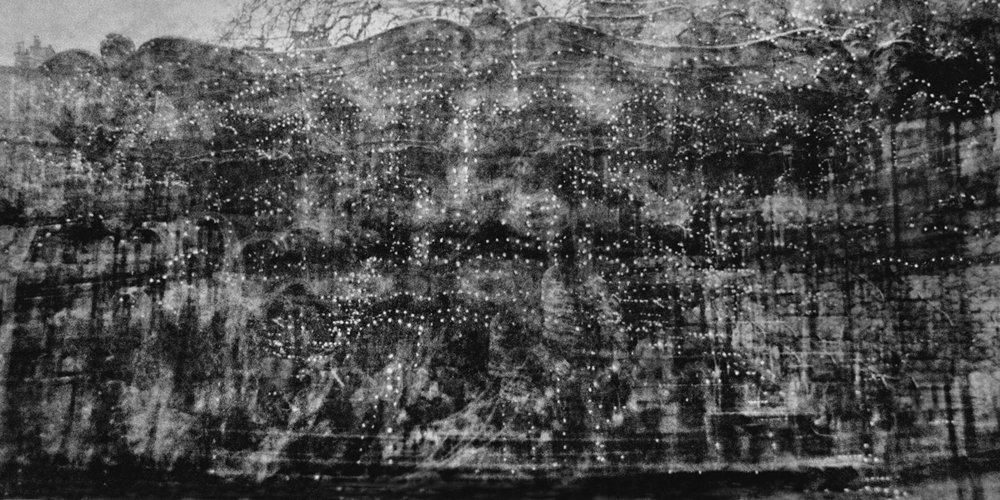

Brain-mapping research suggests dreams are contributed to the transference of the short-term memory, a day or a week into a long-term retention. From an unconscious state the brain awakens and permits the semiconscious to observe the collation, slicing and sequence of multiple scenes. A bioelectric chemical process transmits at great speed, stimulating visual imagery and virtual encounters which, on occasion, we recollect when conscious.

The field of oneirology is a central theme for the project Dreaming of Le Gibet. Over a period of five years I conceive the work in film and employ a multi-layering process to reflect the means of dreaming. Key pieces hold up to 200 exposures within a single frame, each taking up to ten minutes to shoot. The compositions oscillate between figuration and abstraction, appearing both familiar and unfamiliar. My long-term collaborator and curator Samia Ashraf and I edit in stages, to build the development of the sequences. Over time there may be approximately 150 pieces considered, of which there is an assemblage of twenty final pieces.

How does your work in the science field influence your practice?

Areas of science may well be theoretical, abstract and imperceptible—these are optimum conditions for formulating conceptual photographic projects. Artists may have the liberty to position themselves between fact and fiction, as the scope for creativity is perhaps unlimited, determined only by one’s imagination.

Samia and I have recently been appointed the Artist in Residence for the Genome Damage and Stability Centre, part of the School of Life Sciences at the University of Sussex. As the official members of the faculty, we will gain unique access to the work of the research groups at the centre, a leading genomic research institution, enabling us to collaborate with genomic scientists, exploring and responding to the academic research through a body of work. It’s a fascinating area which informs greater understanding; moreover, it inspires further ideas to contemplate.

In Dreaming of Le Gibet you have a piece that depicts the pro EU march following the Brexit referendum, what was it that you were hoping to capture on that day, and what was your experience of being there?

Having bought a lens from the Leica specialist Richard Caplan, I was walking across Pall Mall, and became swamped by an enormous crowd carrying banners and plaques protesting against the result of the UK referendum: to leave the EU. With a manual Leica R 6.2 camera, I began shooting frantically, frame after frame, cranking the film winder over and over, resetting the shutter curtain time and time again. The demonstrating crowd were flanked by the classical buildings of St James’s Street and Piccadilly, and I had an inkling that it may reconfigure the moment with a revolutionary motif. Fortunately, the lighting conditions were favorable; nevertheless, I was nervous the 200 layers might not retain the necessary information on the film, as previous attempts had disintegrated the film into an unusable pulp.

The work became a pivotal piece alluding to Dante’s Inferno and Francisco de Goya’s etchings; the densely black composition would lure the viewer to a stage engulfed by a metaphysical darkness. The piece became a representation of a Point Of View shot from the public gallows; one could say it might symbolize the UK severing its European ties.

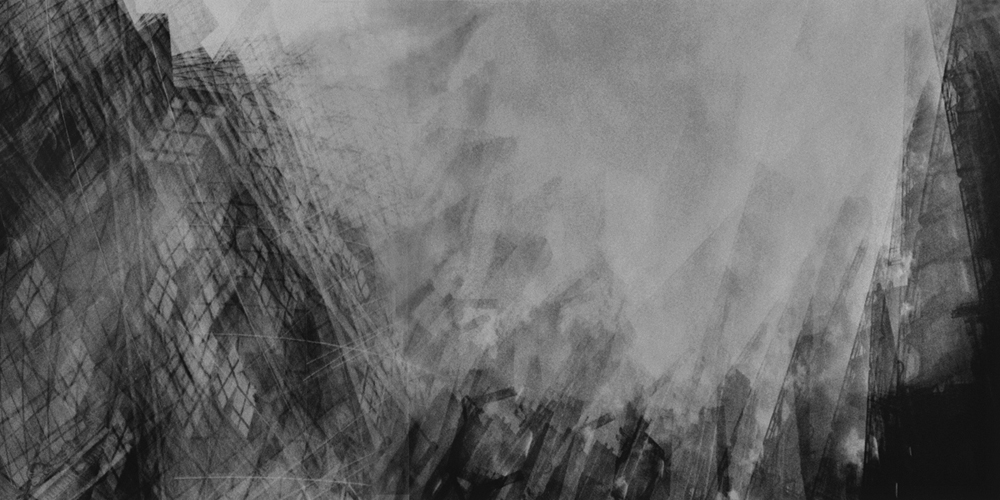

In some of your more architectural shots there are parallels with vorticist painting and photography. Is it a movement you’ve consciously explored and/ or referenced?

The distinct projects are realised by a deep engagement with the urban environment. I am captivated by the palpable physical, mechanical and kinetic energy of the city, the intersection of mass populations weaving through the urban environs, a place characterised by multiple readings. Drawing upon the futurists concern for dynamism rather than the vorticists, other influences include the Bauhaus school with particular reference to László Moholy-Nagy’s photograms. By deconstructing the city, I intend to reimagine the space into contours of geometric shapes. The acute angles can also be attributed to German expressionism, especially citing Hermann Warm, set designer for the feature film The Cabinet of Dr Caligari.