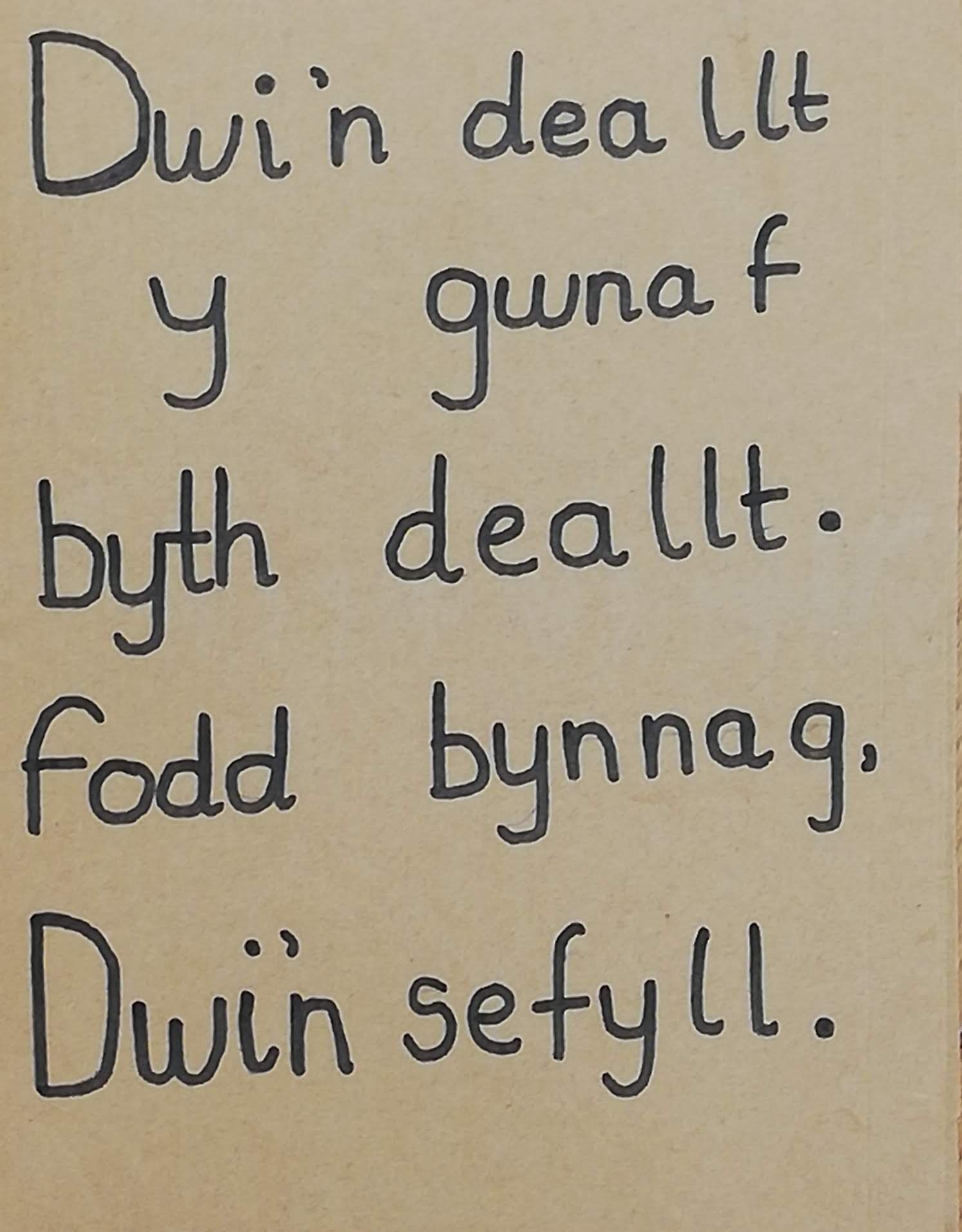

Alongside oversized daffodil hats, stuffed toy dragons, and dolls in traditional Welsh dress, one particular Welsh saying often finds its way into tourist shops around the country: “Cenedl heb iaith, cenedl heb galon,” a nation without a language is a nation without a heart. The country’s pride in its language, as well as its traditional emphasis on song and story, means that Wales is well accustomed to a discussion of voices being high on its priority list.

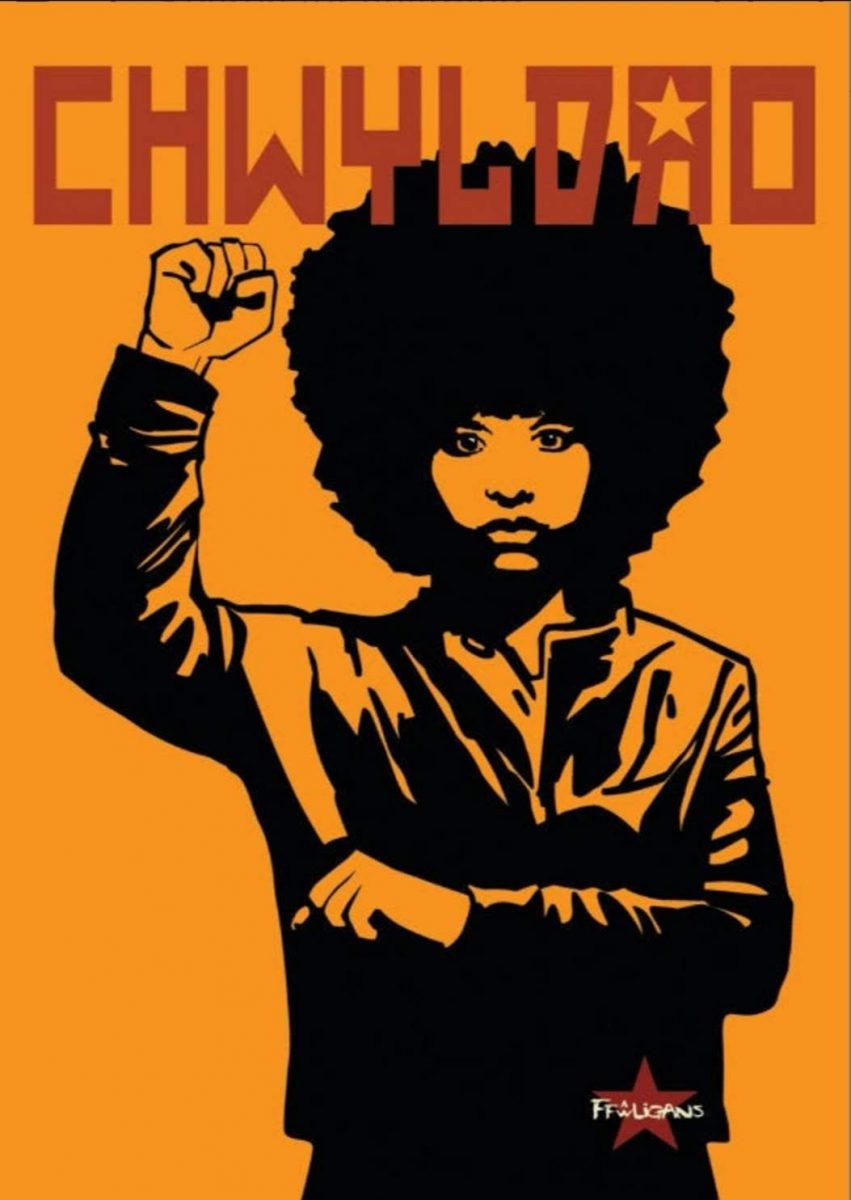

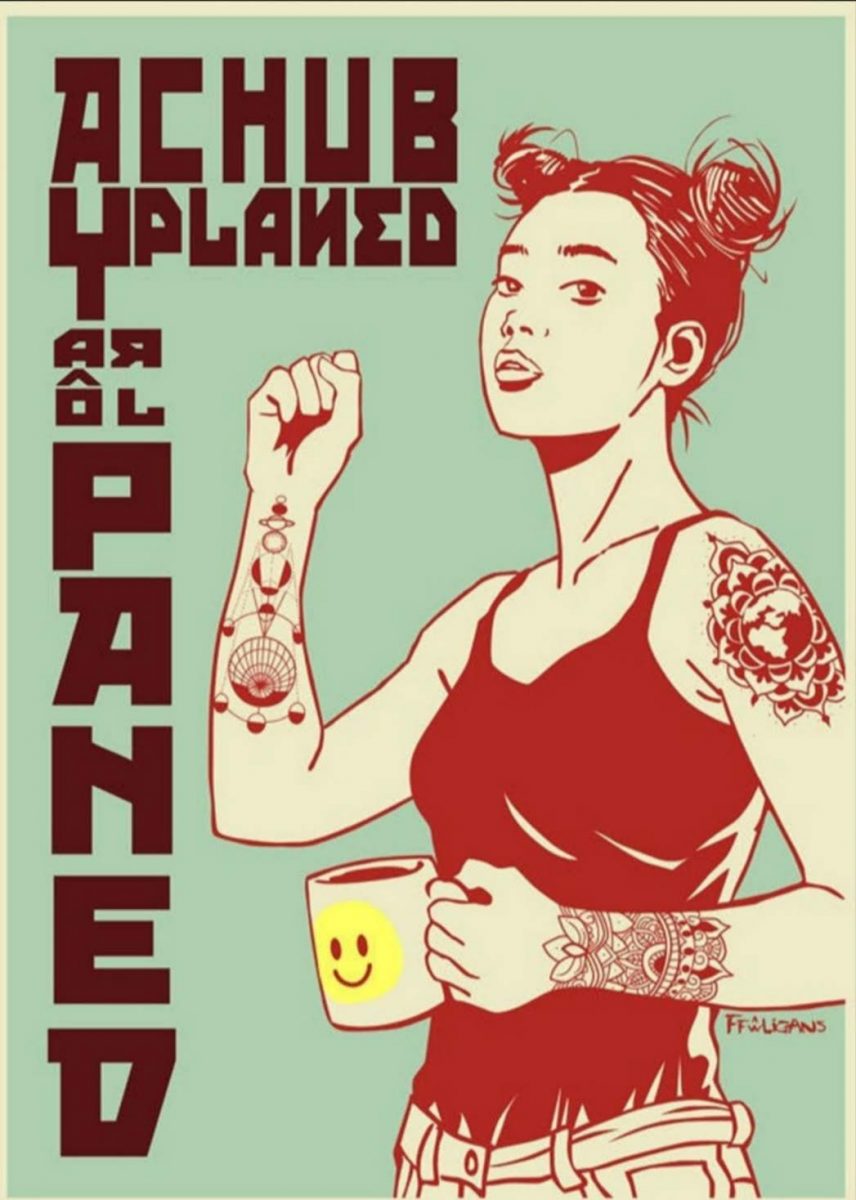

In the past 18 months, however, certain voices have been gaining in volume and number, as shouts of protest from the Black Lives Matter movement in Wales have mixed with the nascent murmurs of Welsh independence and the rallying cries of local intersectional organisations. As the chorus builds, there is a recognition of the need to re-examine perceptions of a past often rose-tinted by nostalgia, alongside the realisation of a potential future which can be rich in stories while also containing a multitude of voices.

A new show at MOSTYN in Llandudno, North Wales is full of these voices. Curated by artists Kristin Luke and Minna Haukka, founders of The Mobile Feminist Library, In Words, In Action, In Connection presents a range of pieces which explore themes of intersectional feminism across history, with both local and international focuses. “The aim was to create a collection which does not pay tokenistic deference to the groups committed to intersectional feminism in Wales, but rather which is the result of many voices contributing to a dialogue,” Luke explains.

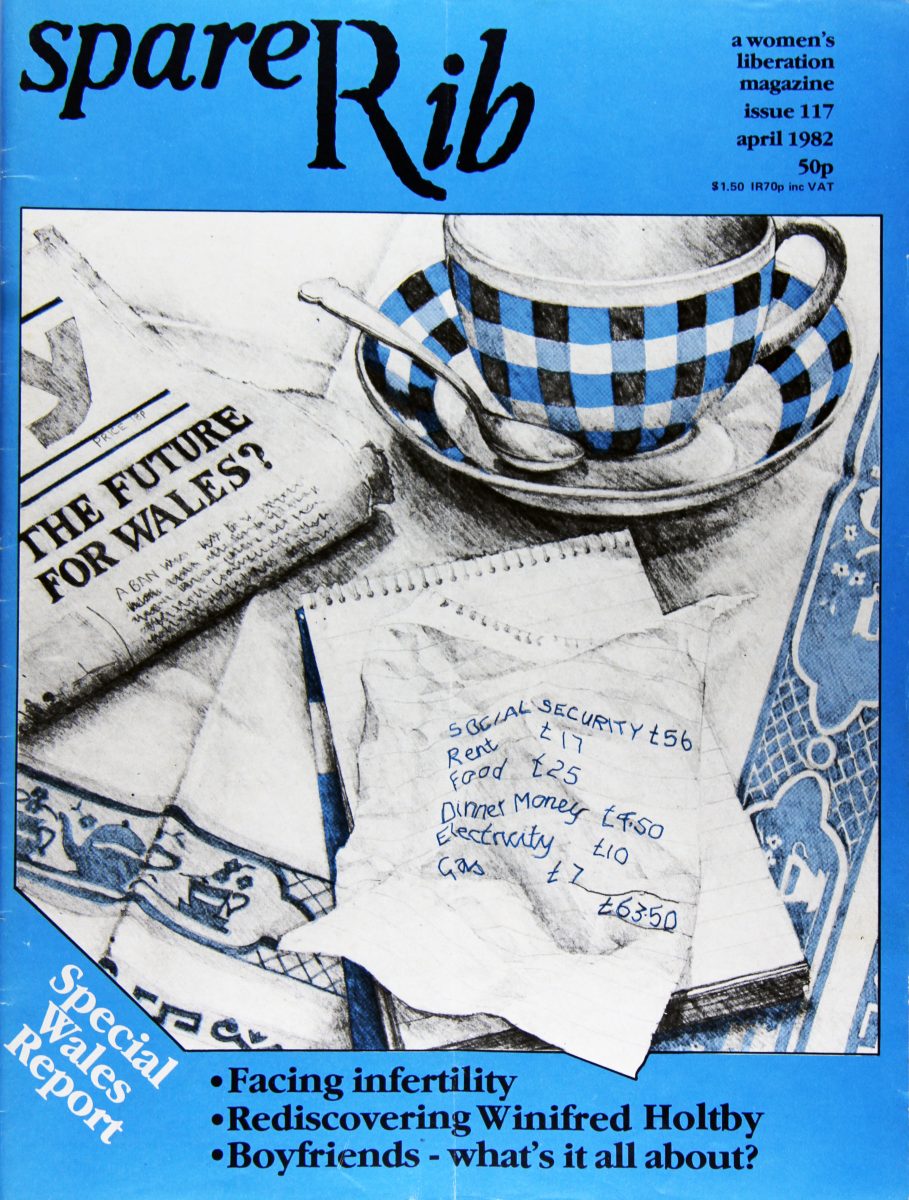

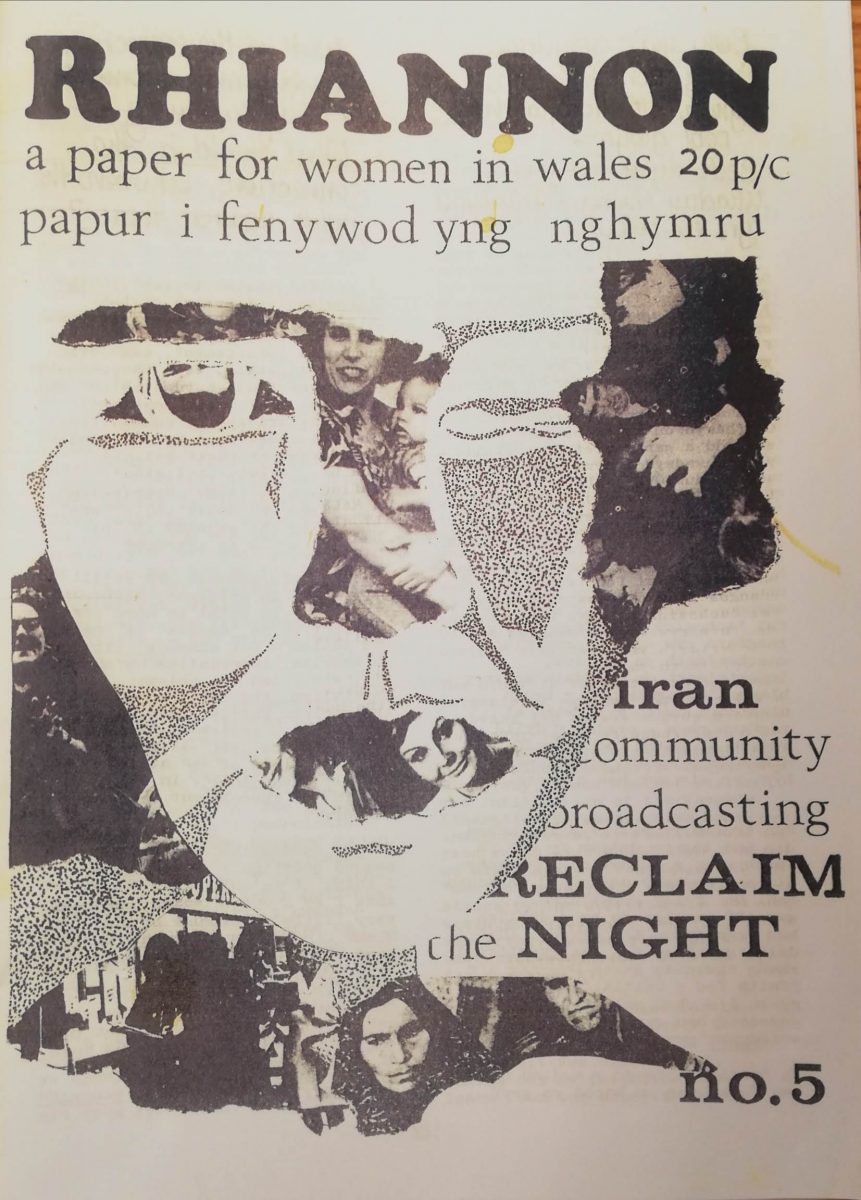

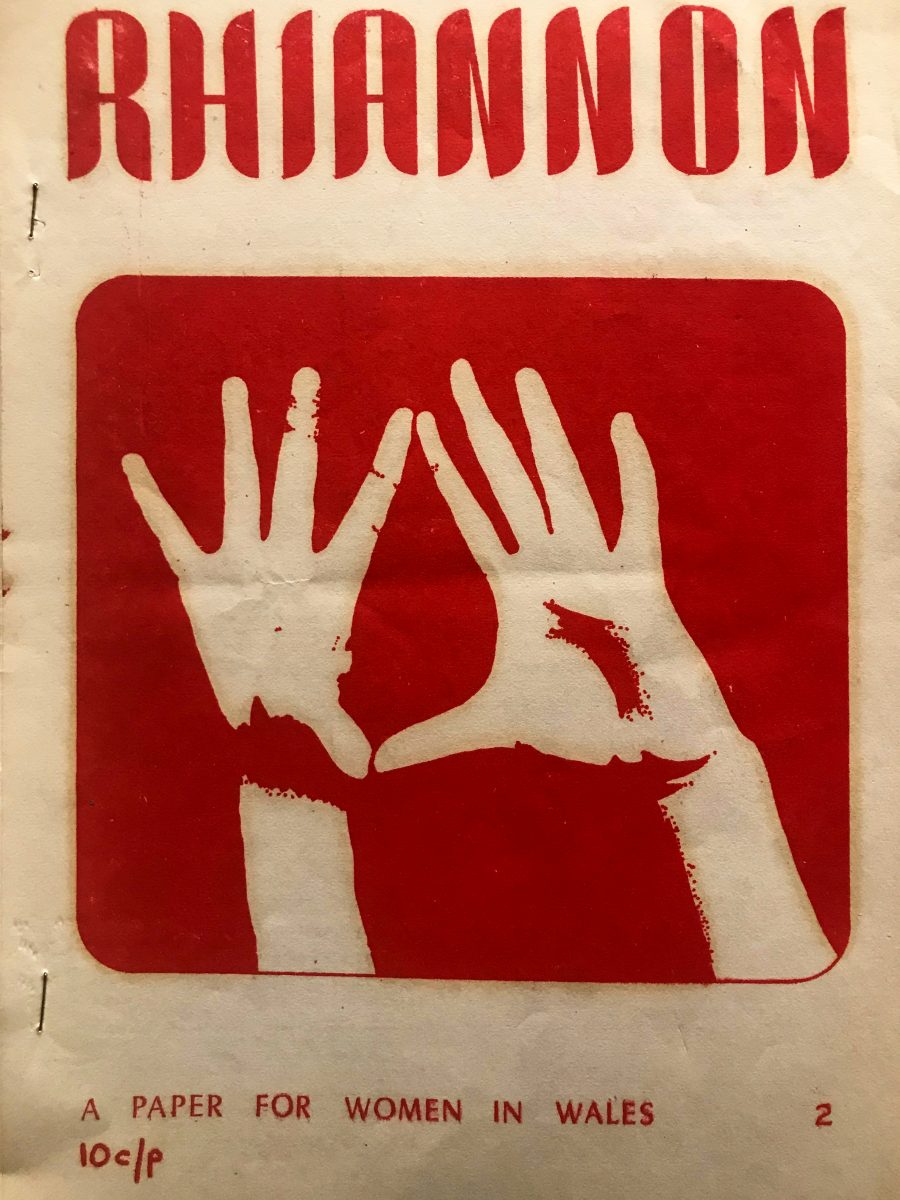

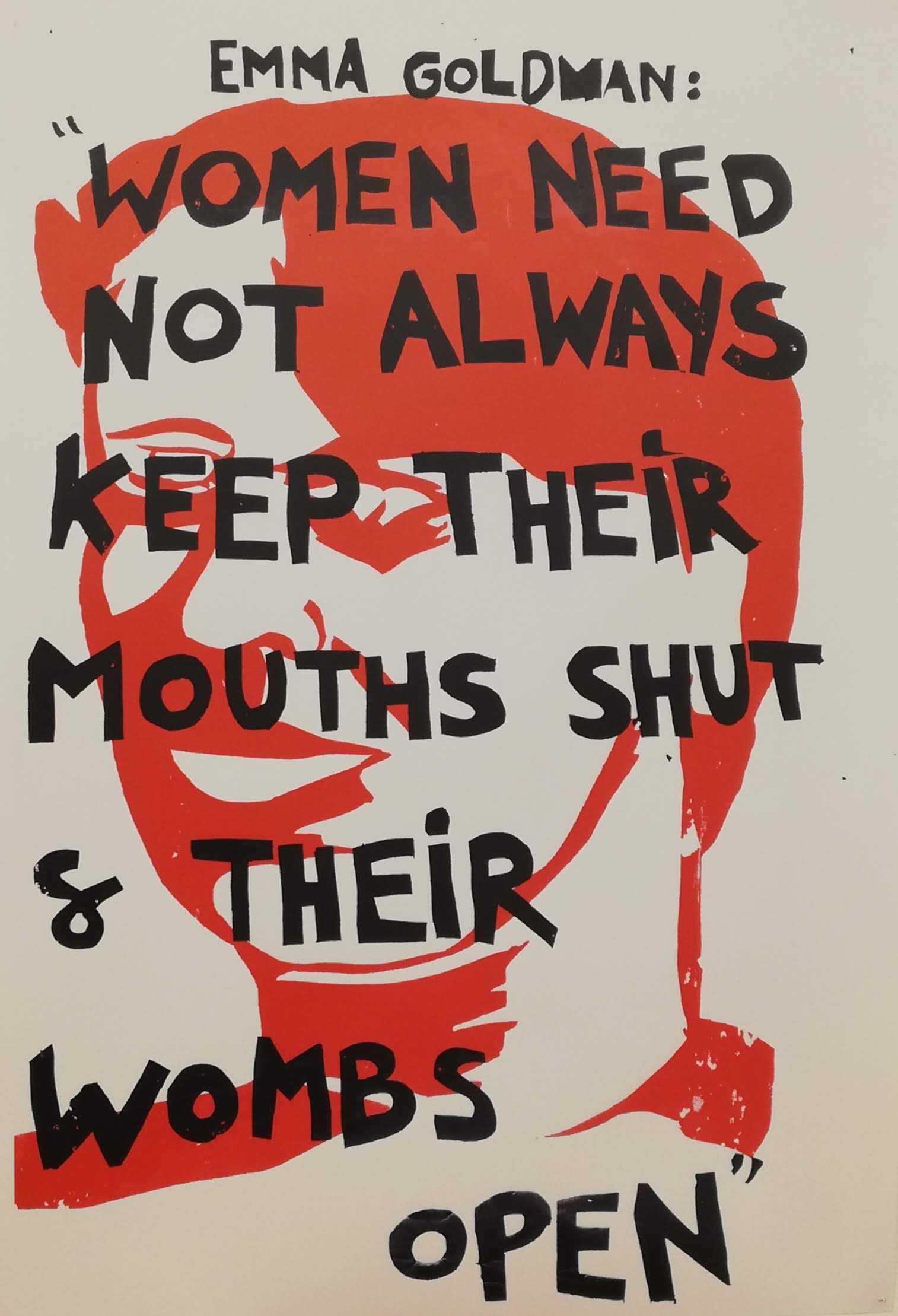

This collection includes documents demonstrating the rich history of feminist communes in Wales, a display of intersectionally feminist magazines, journals, and pamphlets in both Welsh and English, and contributions from a number of contemporary artists and collectives. On one wall, a winding diagram of images and text showcases an interconnected account of intersectional feminism from a local Welsh perspective in conversation with a more international viewpoint.

“We don’t like to view history as inert. We try to revivify, to transfer that energy back to the present”

“This arrangement proposes a non-linear, feminist approach to considering history and time,” says Luke. “The wall diagram connects actions, concepts, and personal narratives across centuries, rather than arranging them according to the years they occurred.”

Many of the contributing artists also emphasise an understanding of history as something that is still happening and still has impact. Sadia Pineda Hameed and Beau W Beakhouse, founders of the Cardiff-based publishing platform LUMIN, argue that stories from the past can be an excellent starting point for the flourishing of radical change. “We don’t like to view history as inert,” they explain. “We try to revivify, to transfer that energy back to the present. Radical histories are continuously being made, and their archiving can be a way to incite and support further action or new ideas.”

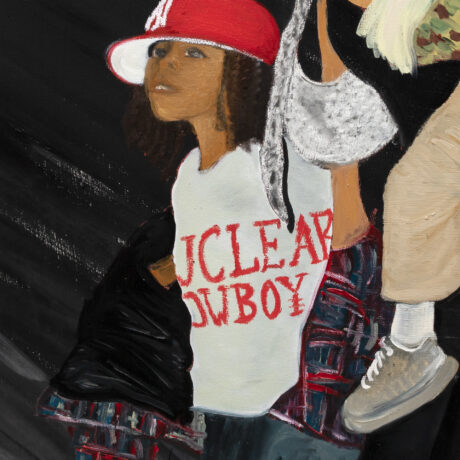

- The Mobile Feminist Gallery: In Words, In Action, In Connection (install), 2021. Photo: Mark Blower

But the dominant versions of history, lacking nuance and accountability, are not always trustworthy. The calls for Welsh independence are laced with the resentful tones of the underdog, neglected by Westminster and deprived of any real power. Projects like Clémentine Schneidermann and Charlotte James’ It’s Called Ffasiwn, Kristin Luke’s the wall is__ and art mural Cofiwch Dryweryn rightly showcase how centuries of cultural suppression and political disregard have left Welsh communities in poverty, decline, and deprivation.

“There is a recognition of the need to re-examine perceptions of a past often rose-tinted by nostalgia”

However this focus on Wales as “England’s first colony” can frame the Celtic nation as being innocent of perpetuating the systems of patriarchy, racism, colonialism and homophobia which have, and continue to, run amok throughout the UK. This is when the narrative needs to be re-examined.

Speaking of their art practice more widely, Pineda Hameed and Beakhouse explain that their approach of examining the relationships between place and history includes listening to the stories that others don’t always want to acknowledge.

“We have tried to develop a way of working intimately and critically with a site, listening to resonances and overlapping histories, including fictional histories and the site’s relationships with labour history, colonialism, ecology, tourism,” the pair explain. “This includes listening to the more speculative and spectral histories, and what is left out in certain retellings.”

When it comes to thinking about the future of Wales, the duo’s thoughts are not of an independent and autonomous country but of independent and autonomous people, of a change in focus from the voice of a nation to the collective voices of the people.

“We don’t believe in continuing projects of nation-building,” they say. “Instead, we’re interested in unbuilding the already existing structures that are based on colonial, supremacist and patriarchal models. We think that what’s needed is a transferral of power away from institutions, to create autonomy at the grassroots level.”

“There is a feeling of potential in this imagining of the future. It offers hope in a shared future where no voice will be overpowering”

This is something which Luke and Haukka also see as central to the exhibition. “We believe that feminist art participates, in both extroverted and introverted ways, in the struggle to resist patriarchal power hierarchies, and undo and re-write dominant historical narratives,” says Luke.

Two of Luke’s favourites pieces in the exhibit are the protest placards and documentation of the 2020 BLM protests, contributed by Casey Duijndam and Robyn Dewhurst. “These two young activists have such an effortless grasp of working in solidarity across the seeming boundaries of identity,” Luke explains. “I feel that their involvement in the project depicts a moment of becoming and shows us what intersectional feminism means for Wales now and where its potential lies.”

There is a feeling of potential in this imagining of the future. It heralds not the refocusing of patriarchal power situated in Cardiff rather than Westminster, but an acknowledgement of a shared history in which the voices of some have been amplified over others. It offers hope in a shared future where no voice will be overpowering.

This is an opportunity to re-imagine that Welsh phrase, often printed on kitchen tea-towels, keyrings and coffee mugs. The country’s heart lies in language, yes, but these languages are numerous and varied, as are the voices that speak them.

Hannah Valentine is a Welsh writer based in London

The Mobile Feminist Library: In Words, In Action, In Connection

At MOSTYN, Llandudno, until 19 September 2021

VISIT WEBSITE