It was 1983, and Lee Jaffe was attending an exhibition opening of his former professor Italo Scanga, when he first met Jean-Michel Basquiat. The pair realized they had mutual respect for each other’s work. Before long the artists were on a Pan Am flight to Japan. Together they travelled through Thailand and Switzerland by car, plane and train. The photographs captured by Jaffe on this journey are brimming with humour and energy and serve as an intimate portrait of the artist as a friend and collaborator. Galerie Eva Presenhuber brings these images together with Jaffe’s paintings in a New York exhibition that, rather than add to the now-immense Basquiat myth, seeks to humanize the artist.

You’ve moved between music and art throughout your career. Is there one that you feel most at home with, and how do they inform one another?

It’s fluid. I’m a musician and an artist. Leaving college before my senior year I went to Brazil and lived in Hélio Oiticica’s house, which was a centre of “a subversive cultural movement—Tropicalia”. Almost daily the singer/guitarist Macalé and the great percussionist Nana Vasconcelos would come by and we would smoke maconia and/or drop LSD and jam for hours on Helio’s terrace with the panoramic view of Rio and the Atlantic Ocean. I also got to work with great filmmakers Neville D’Almeida, Rogério Sganzerla and the brilliant actors Maria Gladys and Helena Ignez and the photographer, Miguel Rio Branco. Tropicalia was a multi-disciplinary movement whose artists’ underlying connection was their defiance of the fascist military government. So the atmosphere in Rio fortified my belief that boundaries between artistic disciplines need not be adhered to.

Lee Jaffe Jean-Michel painting in St. Moritz, 1983—2019 © Lee Jaffe Courtesy the artist. Photo: Matt Grubb

How well did you know of Basquiat before you took the trip with him that is documented in this exhibition? And what are your strongest memories of this trip?

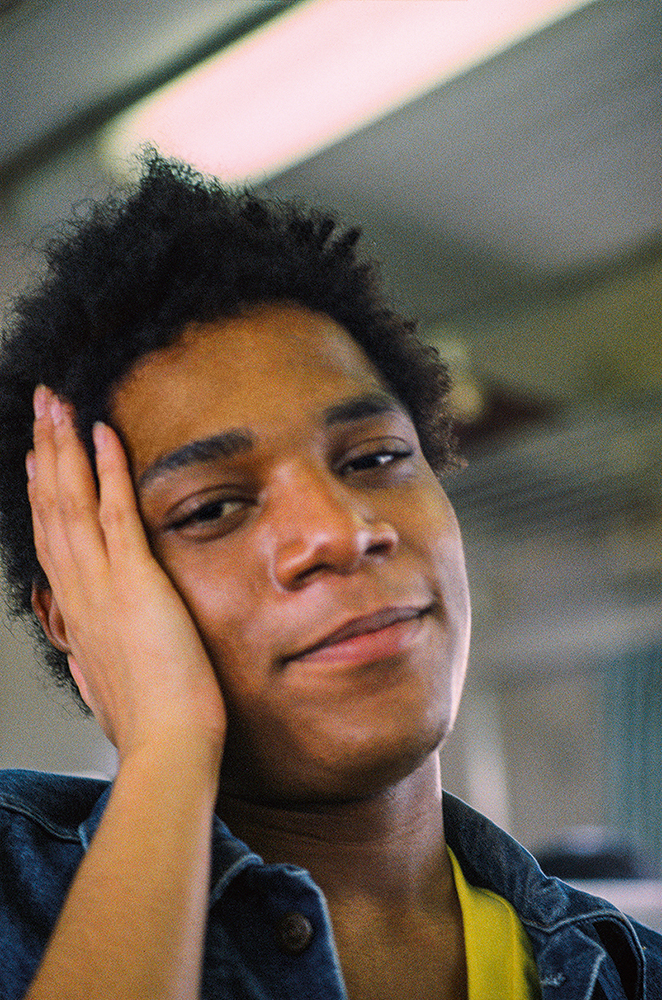

I had just met him—at an exhibition in Los Angeles of my former college professor Italo Scanga—the day before we started our trip, although I felt I already knew him really well. Jean was a reggae fan and knew of my work with Peter Tosh and Bob Marley. I knew of his work from seeing his New York exhibition the year before. I had been really moved by his paintings. The way Bob and Peter used music to engage the audience with the powerful sociopolitical content of their lyrics I saw as parallel to how Jean-Michel used painting. Our first stop was Tokyo. We had wandered into a park and a group of teenagers dressed in fifties rockabilly garb began to silently follow us around. Jean had an incredible magnetism.

“The artist was calm, confident, defiant, and unpretentious—we didn’t need to discuss, as he knew I knew what he wanted”

In Switzerland, we drove from Zurich to St Moritz where Jean had been invited to stay at an art dealer’s house who Warhol had introduced him to. Jean was vexed as when we arrived there were stretched canvases, jars of paint and brushes—no one told him he was there to work. There was a giant cushion that had arrived and was still wrapped in plastic. I suggested that he paint on that and that I would document the process from beginning to end. A few years ago the work showed up at a Sotheby’s private sale, the painted on cover stripped and stretched and the guts removed.

What do you look to capture when you are photographing someone in this way, and what is your process like?

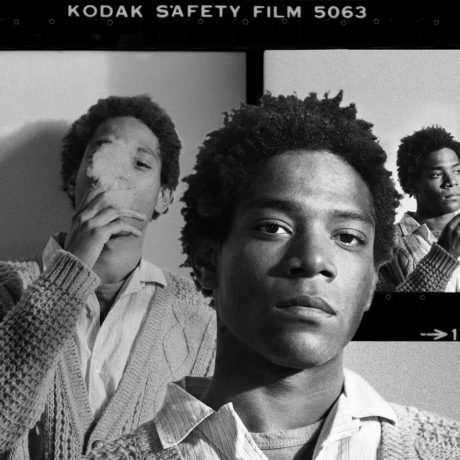

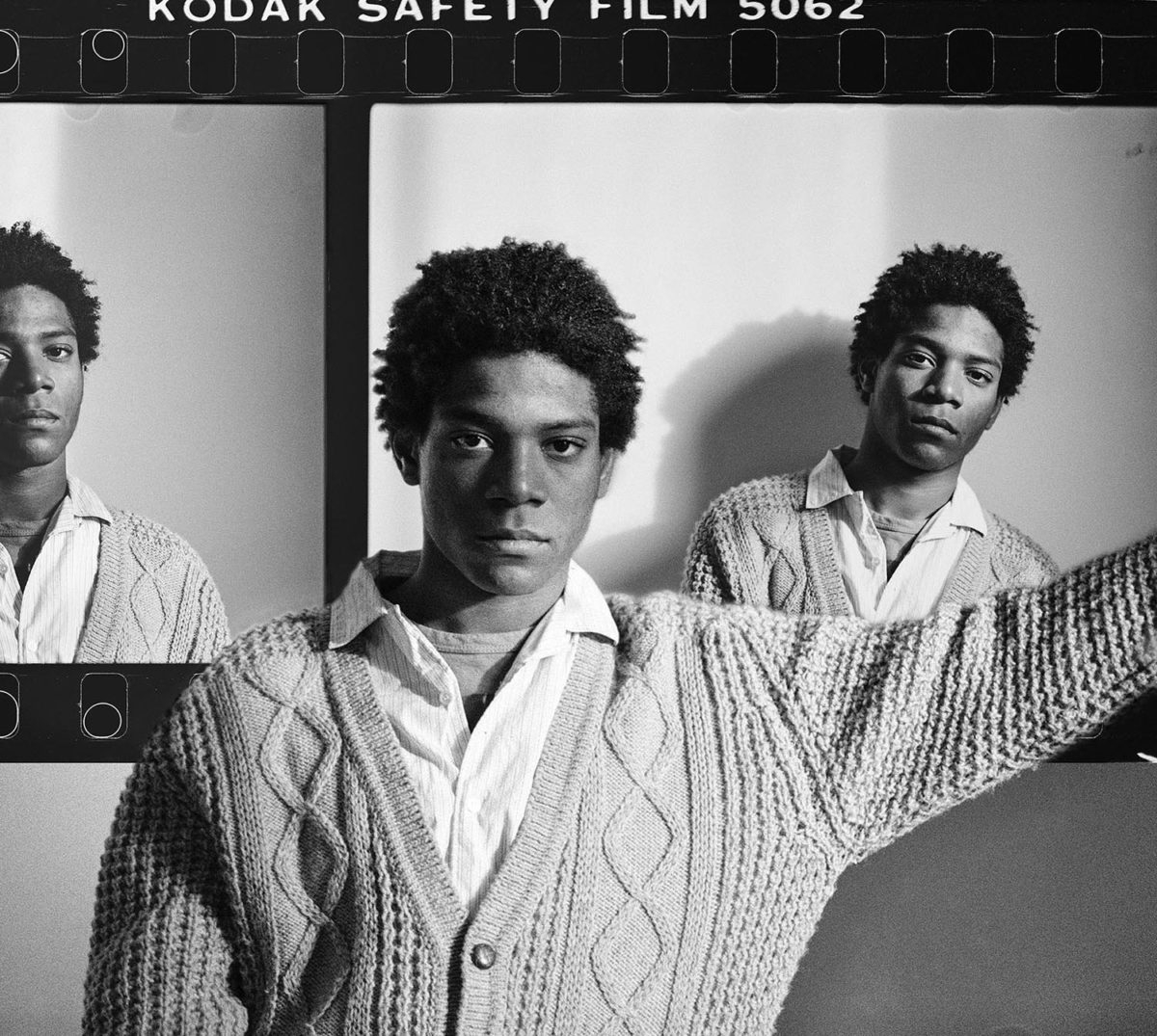

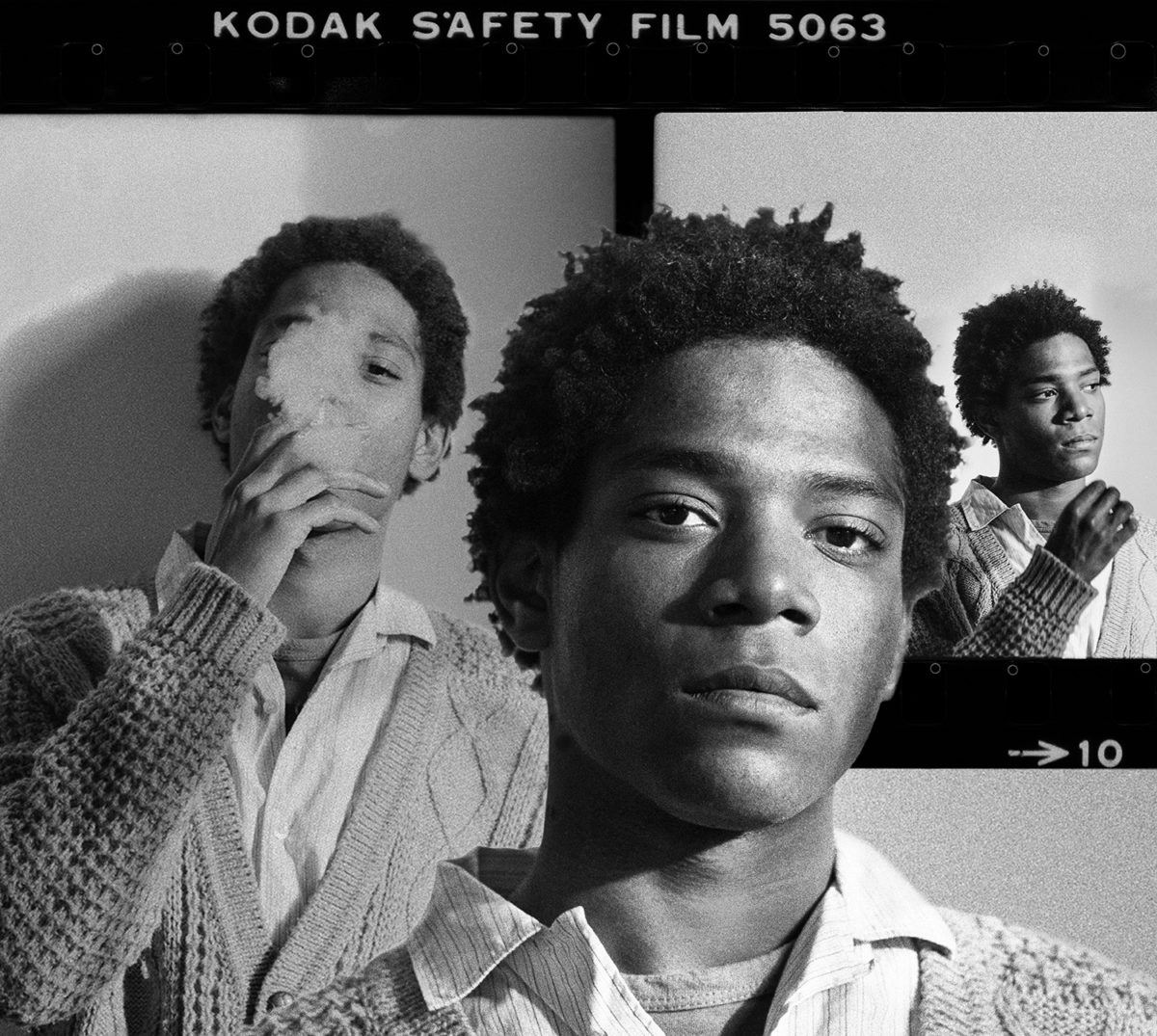

The process was very different for the various groups of images in the show. The black and white pictures came about when Jean called me one afternoon and asked if I could come by Mary Boone Gallery and shoot a portrait for the catalogue for his upcoming show. He asked if I could bring a spliff to smoke. The gallery was empty as it was between shows so we had a bare wall in the pristine white cube. The spliff served the dual purpose of relaxing and simultaneously creating a dichotomous tension, as smoking cannabis in that formal environment was, in those days, very transgressive. Black and white signified serious and I felt would complement the colour reproductions of the paintings to be reproduced in the catalogue. Natural light streaming through glass doors created the soft shadows, the artist was calm, confident, defiant and unpretentious—we didn’t need to discuss, as he knew I knew what he wanted.

The series of five pictures with the girl’s hand that we shot on the bullet train between Tokyo and Kyoto were very different. The idea was to blur the lines of race and gender—the self-conscious poses; Jean’s gaze as the naïve outsider ironic and subversive; the tourist(s) relishing the trip on this technological marvel exotic and post-orientalist—were deliberate and meticulously staged.

- Lee Jaffe, Untitled, 1984—2019 © Lee Jaffe, Courtesy the artist

Coming from a more personal connection with Basquiat, is there anything about him or his practice that you feel is often left out of the mainstream narrative about him?

His ambivalence regarding celebrity. On the one hand, it was anathema to him and on the other he regarded it as necessary to proliferate the message in his work. He was a very humble person and it was something he struggled with.

The text about the exhibition mentions the feeling of being an outsider to the main culture. This is obviously very prevalent in America right now. How do you feel about the current political and social climate in the country?

The US has a foundational problem of conscience. Formed on the subjugation and genocide of the indigenous populations and an economy whose vibrancy depended on slave labour we will continue to have divisiveness and conflict until we collectively are able to have a reckoning with these issues. It’s encouraging that reparations are becoming an open issue of political debate and it is important that Euro-Americans come to actively engage in support of reparations. Of course, it is of utmost importance to acknowledge that present day-slavery needs to be abolished.