This year’s Turner Prize—a serious, solemn quartet of video works, and won by Charlotte Prodger—has been met with (relatively) little fanfare, other than a protest against Luke Willis Thompson’s Autoportrait from collective BBZ London, who argued that his work focused on police brutality against black people is inappropriate.

Outside of the art world, though, it seemed the shortlist was left alone. It’s a far cry from the days when the tabloids would be up in red-topped rage about the prize: “Prize winner Richard Wright shocks world with actual art”, sniffed the Daily Mail in 2009, opening a piece that shocked the wider world (or not) with its ignorance and malice. Even the broadsheets couldn’t veil their disgust at the apparent frivolities and daftness of the art world’s most famous award: “Turner Prize won by man who turns lights off”, read the Telegraph headline of Martin Creed’s 2001 win. “Even by the standards of a prize that has been contested by Chris Offili’s elephant dung paintings, Tracey Emin’s soiled bed and dirty knickers and Damien Hirst’s sliced and pickled animals,” the paper wrote, “Creed’s work is widely considered exceptionally odd and is likely to quicken debate about the prize’s future.”

Today, though, little in the world of art prizes seems to shock. Have we all grown up a little? Are we collectively unshockable? The Turner Prize has certainly changed over time since its inception in 1985, with the aim of encouraging a wider interest in contemporary art and assisting Tate’s acquisition of new works. Only artists aged under fifty could enter between 1991 and 2016; but from 2017 that restriction was lifted.

There’s perhaps a sense that in a post-recession world, art prizes are standing for something different than the jugular hit of shock and awe. Away from the decadence and excess of eighties “greed is good” doctrines and jovial, two-fingers up to the man nineties Brit art bombast, we’re all taking things a little more seriously. Maybe, just maybe, the bleak political and economic times we live in are making us kinder. If any one art prize moment would back up that theory, it’s Theaster Gates’s 2013 Artes Mundi 6 win. Gates, whose practice includes sculpture, installation, performance and urban interventions “that aim to bridge the gap between art and life”, chose to split the £40,000 prize booty amongst the other shortlisted artists.

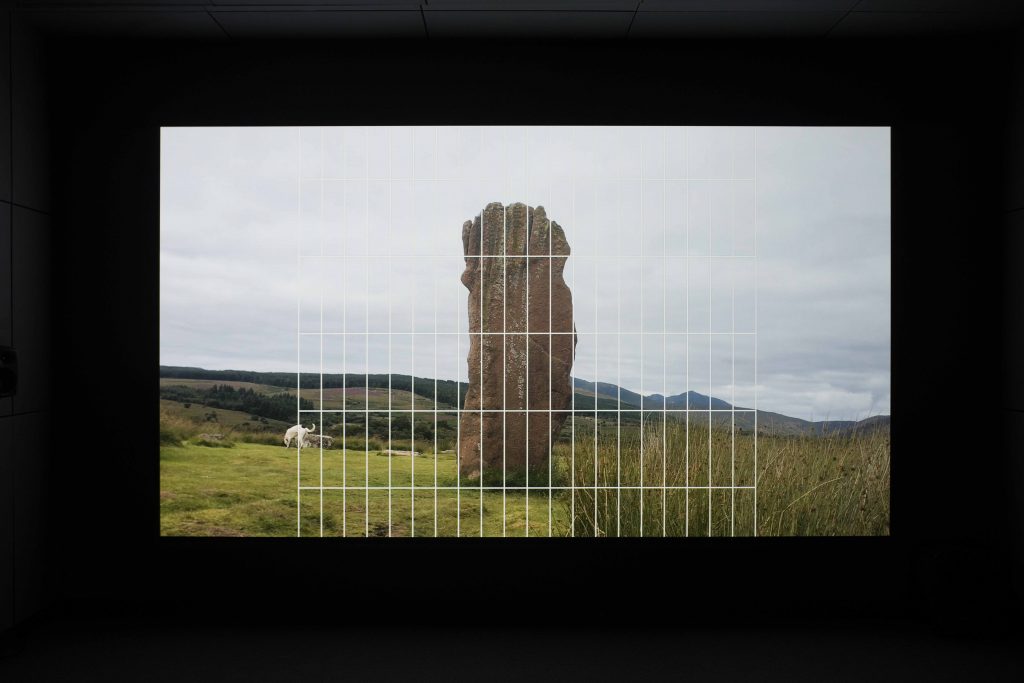

- Charlotte Prodger, Bridgit / Stoneymollen Trail, video still

Indeed, the sense that we’re all looking at art as much for its social impact as its form and message was reflected in this year’s Turner Prize. Judges praised the four 2018 nominees’ commitment to “making a difference to the world today”, and a statement said they “are very proud of the timely and urgent nature” of the shortlist. Prodger won for her solo exhibition Bridgit / Stoneymollen Trail at Bergen Kunsthall; which showed work created using a smartphone that “interweaves bodies, thoughts and landscape”, with references vacillating between JD Sports and standing stones to 1970s lesbian separatism and Jimi Hendrix’s sound recordist. According to the Turner Prize, the jury admired the “painterly quality of Bridgit and the attention it pays to art history” and “the way Prodger explores lived experience as mediated through technologies and histories”.

Without wishing to state the bleeding obvious, the internet has transformed the way art prizes are entered and judged in recent years. In January 2018 the new ArteVue prize launched, which only accepted entries via an app—an intriguing prospect considering the site-specific and conceptual nature of much of the shortlisted work. None of it was the pastel-y, art-directed-to-within-an-inch-of-its-life fodder that’s so usually the art darling of Instagram. The four shortlisted artists were ideas-driven, making complex work that frankly you’d be likely to scroll past if interacting with them in the usual way we consume art through image-led apps.

“The idea of the app and the prize was to democratize art,” ArteVue founder (and funder) Shohidul Ahad-Choudhury said. The entry process was simple and required no particular pedigree: the artist uploaded their images, a brief description of their work, and a PDF, if they wished, and used the #arteprize hashtag to be considered.

For all that innovation and democratization, however, we can’t see the somewhat clinical hashtag process taking over from traditional art prize entry routes and criteria any time soon. We’re not sure how video pieces would necessarily fare, for instance; such as the superbly eerie work of Daria Martin, who won the 2018 Film London Jarman Award for her primarily 16mm film works examining subjects including robots, dreams, the mind and magic within unusual spaces to transmit a sense of movement between internal and external worlds, and varying levels of consciousness. Big ideas indeed; too big for a simple app upload, perhaps?

Hot on the heels of the announcement of the Jarman Award comes our very own news: this Friday (7 December) we’ll be sharing the news of the winner of our very own Elephant x Griffin Art Prize. This year marks the first time Elephant has supported an art prize, but the competition itself—formerly known just as the Griffin Art Prize—has been in existence for six years, celebrating UK-based artists working across all mediums. As we stated in our callout, we were looking for “dynamic, committed, emerging artists with the potential to become international stars” who reflect Elephant’s motto “Life through Art” through work that engages with the wider issues of the world at large.

The shortlist for the Elephant x Griffin Art Prize was announced in October, with the eleven shortlisted artists working across a wide range of media and with deliciously varying approaches to their practice.

The winner will receive a £5,000 cash stipend, £2,000 of studio rent within 2019 at a location of choice within the UK, £3,000 RRP value of art materials from fine art brands (Winsor & Newton, Liquitex and Conté à Paris) and professional support and mentoring programme from the Elephant team. Stay tuned!